Evolution of the Knowledge Mapping of Climate Change Communication Research: Basic Status, Research Hotspots, and Prospects

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Climate Change Communication

2.1. Concepts Related to Climate Change Communication

2.2. The Conceptual Connotation of Climate Change Communication

3. Research Methods and Literature Collection

3.1. Research Methods

3.2. Literature Collection

4. Analysis of Bibliometric Results

4.1. Basic Distribution of Literature

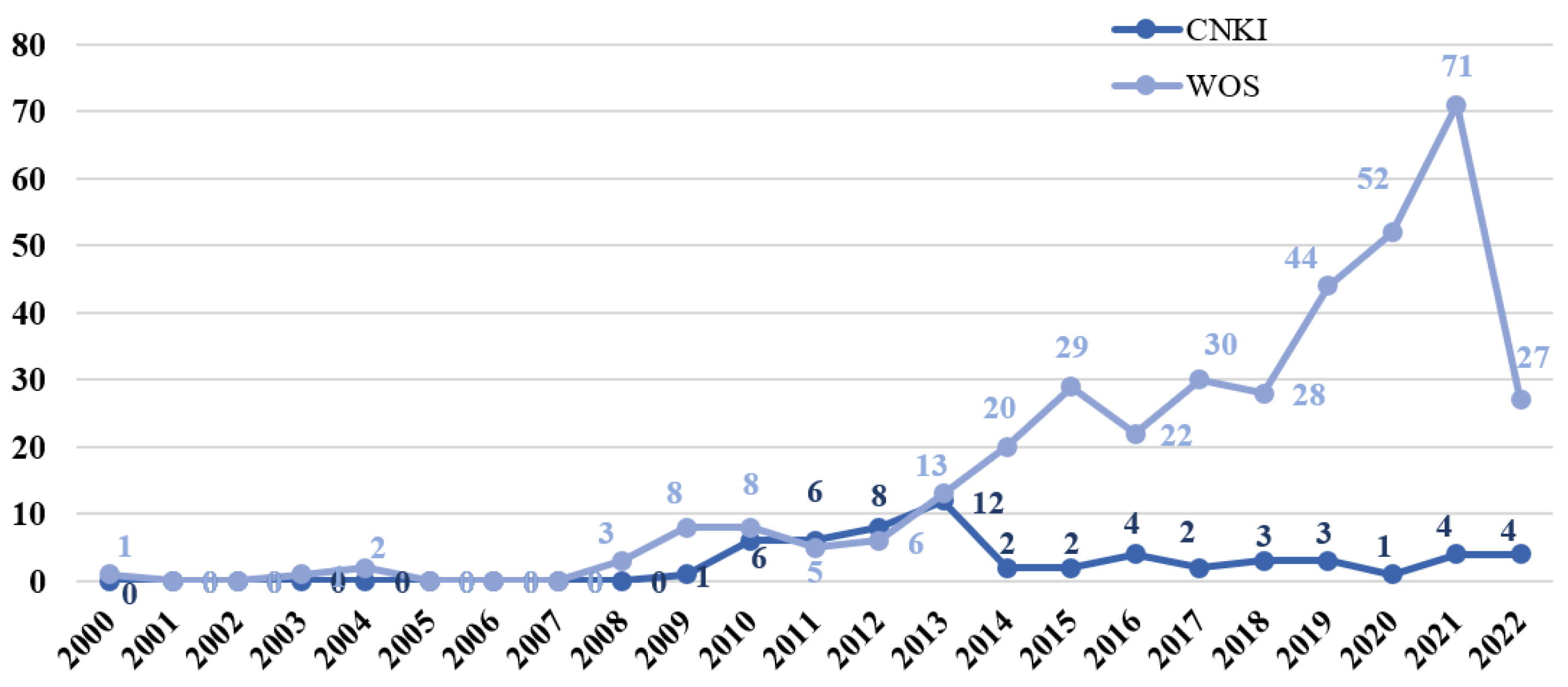

4.1.1. Analysis of the Number of Articles Published

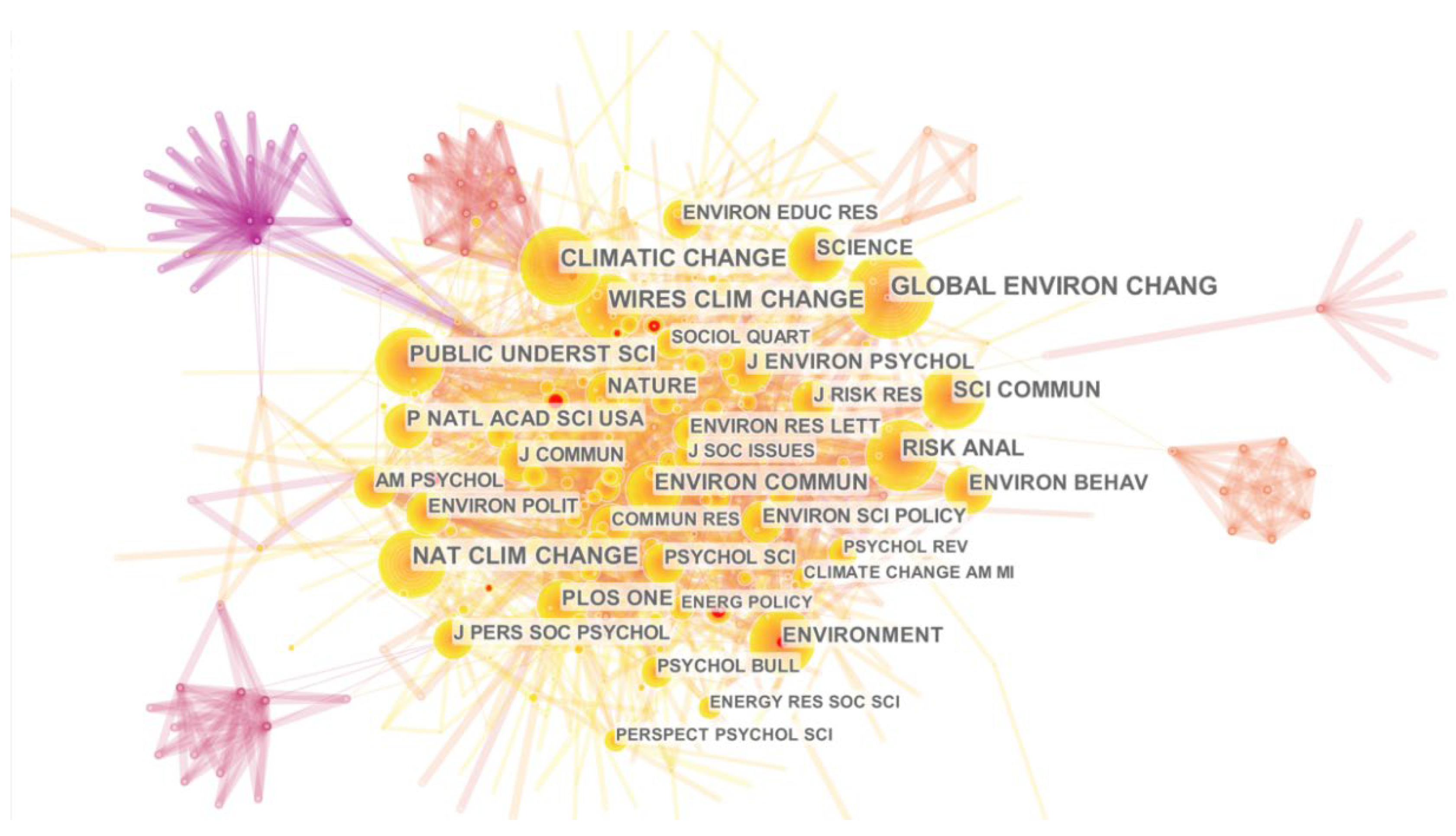

4.1.2. Analysis of Core Journals

4.2. Literature Visualization Analysis

4.2.1. Keyword Analysis

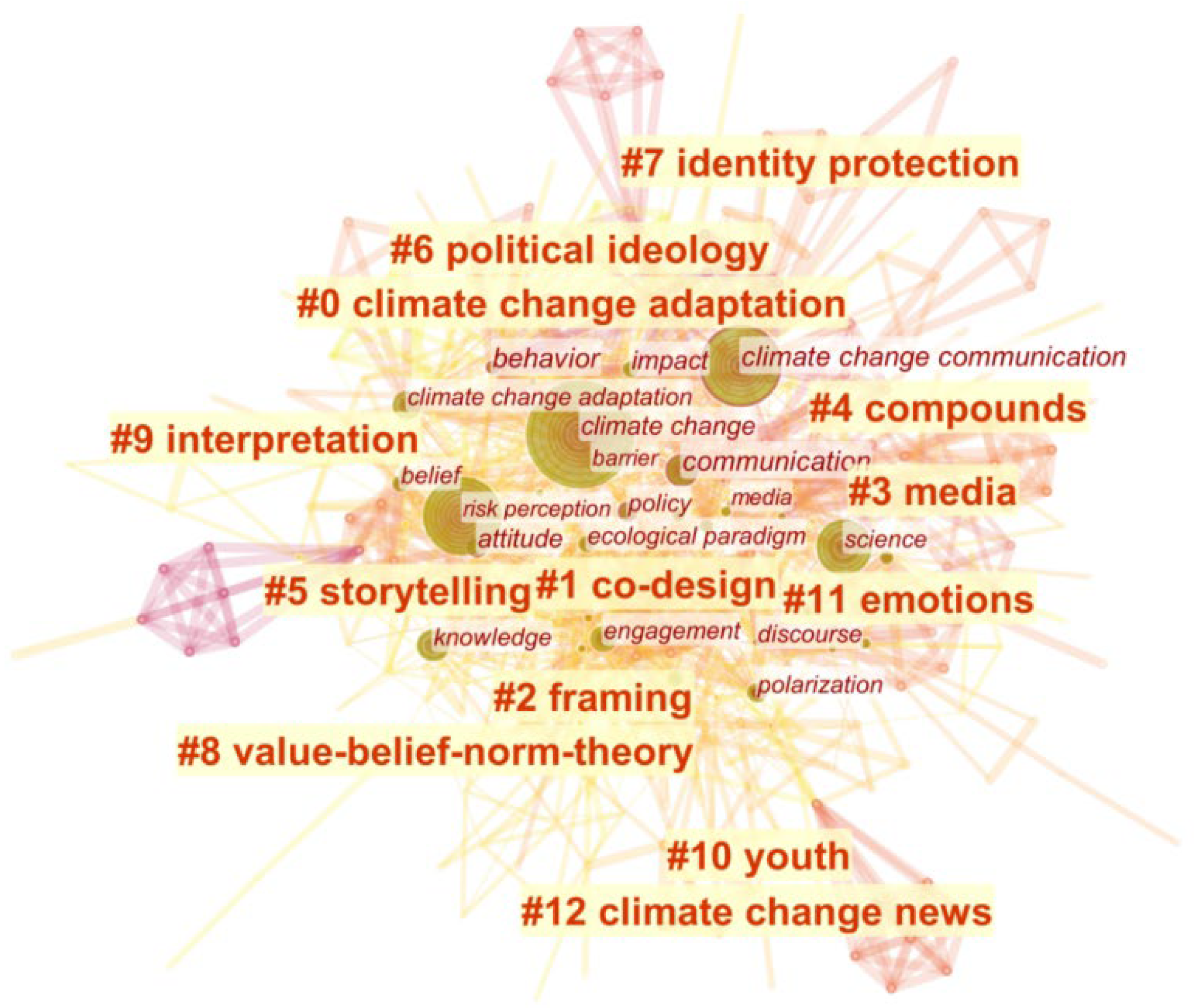

4.2.2. Keyword Clustering Analysis

4.2.3. Literature Co-Citation Analysis

- (1)

- The emergence of climate communication research

- (2)

- Differences in public perception of climate change

- (3)

- Influencing factors of climate change communication

- (4)

- Key elements of the climate change communication process

- (5)

- The important role of the media in climate change communication

- (6)

- Effective strategies for climate change communication

5. Research Conclusions and Prospects

5.1. Research Conclusions

- (1)

- In terms of the number of articles published in the WOS database, the earliest official climate change communication literature in English appeared in 2000. The number of articles published has gradually increased, reaching its first peak in 2015. After that, the number of articles has generally shown a steady growth trend, and the number of articles in 2021 reached the highest value in recent years. In contrast, Chinese climate change communication research started late, and the number of articles published is relatively small; the first Chinese literature on climate change communication appeared in 2009. Although domestic research in general continues to focus on this phenomenon, there is still much room for growth compared to international research.

- (2)

- In terms of the number of publications, Global Environmental Change, Climatic Change, Nature Climate Change, and WIREs Climate Change are highly cited journals. In terms of impact, American Sociological Review, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, American Psychologist, and Environmental Research Letters are among the top journals.

- (3)

- Climate change communication research hotspots are centered around climate change news, and the value–belief–norm theory is one of the most commonly used research theories. The media is a channel for climate change communication. Climate change-related issues can be interpreted through co-design, frame setting, creating climate change-related compound words, and storytelling. Political ideology is a strong predictor of forming public climate change views. Since climate change has political attributes, people from different political parties or groups form their climate change views through identity protection. In addition, youth play an important role in climate change communication.

- (4)

- The main research on climate change communication can be summarized in the following six aspects: the emergence of climate change communication research, public perception differences of climate change, factors influencing climate change communication, key elements of the climate change communication process, the important role of the media in climate change communication, and effective strategies for climate change communication.

5.2. Research Prospects

- (1)

- In terms of research content, the current research just describes and explores the current situation or phenomenon of climate change communication, but does not go deeper into it, and there are many shortcomings in research on the impact of climate change communication in terms of communication methods, communication channels, forms of information diffusion, and network structures. As Li (2013) mentioned in their study, although domestic and foreign institutions have conducted surveys specifically covering Chinese public perceptions of climate change, most of these surveys only examine public perceptions of climate change issues and related policies and actions, and rarely focus on the issues of channels, sources, contents, and strategies in climate change communication. Moreover, these surveys only stay at the level of data analysis, lacking in-depth theoretical analysis and innovative ideas [39]. In addition, the evaluation of communication effectiveness should be strengthened. Every information communication activity by the government costs a certain amount. Therefore, certain evaluation criteria should be used to judge whether the government’s information communication activities to address climate change are effective [51]. The evaluation of communication effects can be measured from cognitive, attitudinal, and behavioral aspects by adopting scientific indicators to construct evaluation methods according to different media, or based on the construction of a multi-modal fusion communication database of information, the characteristic expressions of each modality, such as gesture, expression, text, and voice, can be studied to complete the feedback of the effect of media content information and user interaction information, which can be fed into the design of media communication effectiveness improvement.

- (2)

- In terms of research context, the information technology revolution and media iteration have brought about a new communication landscape, and the expression and interpretation of a specific media message have a profound impact on the effectiveness of that message and the audience’s perception. The means of information acquisition for generation Z have changed significantly from those of the previous generation. Mobile and visualization are the main trends in media consumption for generation Z. Instagram, Snapchat, and TikTok are three emerging social media platforms that are rapidly growing based on mobile visual information [52]. Communication technologies, such as the Internet, new media (e.g., blogs, Wikipedia, Twitter, computer games, and, especially, mobile media), and visual technologies have also made great strides. Therefore, in this new research context, applying machine learning and deep learning methods to mine data in different modalities in real media, building models to correlate and process multi-modal media data, and studying climate change communication in a multi-modal convergence perspective can help further promote public understanding of climate change and facilitate greater public participation in climate change action.

- (3)

- In terms of research methods, framing is a very important communication choice [53], which can have a great impact on the persuasiveness of communication, public attitude change, trust, and participation. Some foreign scholars have focused on climate change communication strategies and techniques by using several empirical research methods, such as experimental methods, content analysis, and survey interviews, starting from disciplines such as communication, psychology, and public opinion [13]. The current development of computational social science, new media technology, and the advent of the era of big data has expanded the ideas of climate change communication research, and previously unavailable group data has gradually become possible. The use of big data, machine learning, network construction, and other methods to systematically and deeply study the relevant subjects and social operations in climate change communication is a major trend that cannot be ignored in future research in the field of climate change communication.

- (4)

- In terms of research paradigms, future research must focus on how different communication approaches and strategies can encourage deeper personal concern and lifestyle engagement with climate change [51]. At present, whether it is environmental communication, science communication, or risk communication, all of them have begun to emphasize the transition from the “technical paradigm” of public understanding to the “democratic paradigm” that focuses on public participation. China’s climate change communication also needs more local, on-the-ground stories that are more relevant to the public. In this regard, it is necessary to activate user resources across the web to help popularize the production and communication of climate knowledge [54]. Since the new research context and paradigm may involve construal level theory, risk amplification theory, emotional contagion theory, planned behavior theory, etc., variables such as psychological distance and psychological barriers should be added, and network characteristics such as scale-free networks and complex networks should be used to do some exploration of climate change communication in combination with contagion or communication models. At the same time, it is necessary to follow the trend of the era of the knowledge economy and guide the whole society to participate in climate change communication.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moser, S.C. Communicating climate change: History, challenges, process and future directions. Wiley Interdisc. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2010, 1, 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, X.M. The absence of science: Climate change communication in the new media environment in China: A case of online video sharing sites. J. Res. 2018, 1, 73–80, 151. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Moser, S.C. Reflections on climate change communication research and practice in the second decade of the 21st century: What more is there to say? Wiley Interdisc. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2016, 7, 345–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.B. Chinese path: Climate communication and governance from the perspective of a two-tier game. Beijing Soc. Sci. Acad. Press. 2018, 21–22, 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, N. Ecological Communication; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Covello, V.T.; Slovic, P.; Von Winterfeldt, D. Risk communication: A review of the literature. Risk Abstr. 1986, 3, 171–182. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.F. Discussion on strategies of health communication in post-epidemic era. J. Lover 2022, 5, 74–76. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bernal, J.D. The Social Function of Science; George Routedge and Sons: London, UK, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, X.M.; Su, Y. The academic path and realistic dimension of Chinese political communication research. Soc. Sci. China 2014, 2, 79–95. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, B.W.; Qin, Z.; Zheng, Q. The public’s role orientation and action strategy in climate communication—Thinking based on China’s "green development" concept. News Writing. 2021, 6, 45–51. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Climate Change and Communication: Coping Strategies for Media, Scientists and the Public; Fangfang, G., Translator; Zhejiang University Press: Hangzhou, China, 2019; Volume 20–26, pp. 48–51. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, B.W.; Li, Y.J. The role of news media in climate communication and its strategies and methods—Taking the report of the Copenhagen Climate Conference as an exampl. Mod. Commun. J. Commun. Univ. China 2010, 11, 33–36. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, B.W.; Li, Y.J. Research on climate change and climate change communication. Chin. J. Commun. 2011, 33, 56–62. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. CiteSpace II: Detecting and visualizing emerging trends and transient patterns in scientific literature. J. Am. Soc. Inform. Sci. Technol. 2006, 57, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Song, N.Q.; Huang, J.; Zhou, X.D. Review and prospect of international research on preschool children’s movement development assessment: A CiteSpace-based visual analysis. Chin. J. Tissue Eng. Res. 2021, 25, 1270–1276. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, X.D.; Ai, W.Y.; Xiang, H. The framework of network media climate communication from the perspective of ecology—Taking People’s Daily Online and Sina.com as examples. Mod. Commun. J. Commun. Univ. China 2016, 38, 67–71. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.H.; Yan, J.; Xie, Y.; Jia, H.P. Why the public has insufficient trust in scientific conclusions on climate change. Clim. Chang. Res. 2022, 18, 97–109. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xie, P. Study of international anticancer research trends via co-word and document co-citation visualization analysis. Scientometrics 2015, 105, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapiains Arrué, R.; Ugarte Caviedes, A.M. Contribuciones de la psicología al abordaje de la dimensión humana del cambio climático en Chile (Segunda Parte). Interdisciplinaria 2017, 34, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; McCright, A.M.; Yarosh, J.H. The political divide on climate change: Partisan polarization widens in the US. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Devel. 2016, 58, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulic, A.; Angel, J.; Sheppard, S. Designing futures: Inquiry in climate change communication. Futures 2016, 81, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A.; Rayner, T.; Schroeder, H.; Adger, N.; Anderson, K.; Bows, A.; Whitmarsh, L. Going beyond two degrees? The risks and opportunities of alternative options. Clim. Policy 2013, 13, 751–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corner, A.; Roberts, O.; Chiari, S.; Völler, S.; Mayrhuber, E.S.; Mandl, S.; Monson, K. How do young people engage with climate change? The role of knowledge, values, message framing, and trusted communicators. Wiley Interdisc. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2015, 6, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, L.; Nisbet, M.C.; Nesbit, A.; Leiserowitz, A.; Maibach, E. The Climate Change Generation? Survey Analysis of the Perceptions and Beliefs of Young Americans. In Yale Project on Climate Change and the George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication. 2010. Available online: https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/2010_03_The-Climate-Change-Generation.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Becsi, B.; Hohenwallner-Ries, D.; Grothmann, T.; Prutsch, A.; Huber, T.; Formayer, H. Towards better informed adaptation strategies: Co-designing climate change impact maps for Austrian regions. Clim. Chang. 2020, 158, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nerlich, B.; Koteyko, N. Compounds, creativity and complexity in climate change communication: The case of ‘carbon indulgences’. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2009, 19, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, K.L.; Webler, T.N. Social norms and efficacy beliefs drive the alarmed segment’s public-sphere climate actions. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2016, 6, 879–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Iss. 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, P.S.; Nisbet, E.C. Boomerang effects in science communication: How motivated reasoning and identity cues amplify opinion polarization about climate mitigation policies. Commun. Res. 2012, 39, 701–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Maibach, E.W.; Zhao, X.; Roser-Renouf, C.; Leiserowitz, A. Support for climate policy and societal action are linked to perceptions about scientific agreement. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2011, 1, 462–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, K.H.; Cappella, J.N. Echo Chamber: Rush Limbaugh And The Conservative Media Establishment; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Stroud, N.J. Polarization and partisan selective exposure. J. Commun. 2010, 60, 556–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall Jamieson, K.; Hardy, B.W. Leveraging scientific credibility about Arctic sea ice trends in a polarized political environment. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111 (Suppl. S4), 13598–13605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahan, D.M.; Peters, E.; Wittlin, M.; Slovic, P.; Ouellette, L.L.; Braman, D.; Mandel, G. The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2012, 2, 732–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahan, D.M.; Peters, E.; Dawson, E.C.; Slovic, P. Motivated numeracy and enlightened self-government. Behav. Public Policy 2017, 1, 54–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerlich, B.; Koteyko, N.; Brown, B. Theory and language of climate change communication. Wiley Interdisc. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2010, 1, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Chinese think tanks’ role and action strategies in the climate change communication. Think Tank Theory Pract. 2021, 6, 58–66. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.J. Resources, channels, content: Strategies of climate change communication based on the Chinese public survey. China J. Commun. 2013, 35, 67–83. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- China Climate Communication Project Center. A Survey Report on the Public Awareness of Climate Change and Climate Communication in China; China Climate Communication Project Center: Beijing, China, 2012. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Stokes, B.; Wike, R.; Carle, J. Global concern about climate change, broad support for limiting emissions. Pew Research Center. 2015, 5, 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hornsey, M.J.; Harris, E.A.; Bain, P.G.; Fielding, K.S. Meta-analyses of the determinants and outcomes of belief in climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2016, 6, 622–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, T.A.; Nisbet, M.C.; Maibach, E.W.; Leiserowitz, A.A. A public health frame arouses hopeful emotions about climate change. Clim. Chang. 2012, 113, 1105–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCombs, M.E. The agenda-setting function of the press. In The Press; Overholser, G., Jamieson, K.H., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, K.M. Drought, debate, and uncertainty: Measuring reporters’ knowledge and ignorance about climate change. Publ. Understand. Sci. 2000, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krosnick, J.A.; MacInnis, B. Frequent Viewers of Fox News Are Less Likely to Accept Scientists’ Views of Global Warming. Available online: https://woodsinstitute.stanford.edu/system/files/publications/Global-Warming-Fox-News.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2010).

- Feldman, L.; Maibach, E.W.; Roser-Renouf, C.; Leiserowitz, A. Climate on cable: The nature and impact of global warming coverage on Fox News, CNN, and MSNBC. Int. J. Press Politics 2012, 17, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goritz, A.; Schuster, J.; Jörgens, H.; Kolleck, N. International public administrations on Twitter: A comparison of digital authority in global climate policy. J. Comp. Policy Anal. Res. Pract. 2022, 24, 271–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Personally relevant climate change: The role of place attachment and local versus global message framing in engagement. Environ. Behav. 2013, 45, 60–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’neill, S.; Nicholson-Cole, S. “Fear won’t do it” promoting positive engagement with climate change through visual and iconic representations. Sci. Commun. 2009, 30, 355–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, L.N.; Shen, X.L. A study of government information dissemination on tackling climate change. Chin. Publ. Admin. 2015, 11, 131–134. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.N.; Shi, A.B. New trends of global news communication in 2022—Analysis based on six hot topics. Shanghai J. Rev. 2022, 1, 57–65. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Nisbet, M.C. Communicating climate change: Why frames matter for public engagement. Environment 2009, 51, 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, B.W.; Zheng, Q.; Qin, Z. Strategic orientation and action strategy of climate communication in China under the background of ecological civilization construction and green development concept. J. Lover 2021, 5, 17–23. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

| Related Concepts | Concept Connotation |

|---|---|

| Environmental communication | Any kind of communication practice and approach to the expression of environmental issues that aims to change the structure and discourse system of social communication [5]. |

| Risk communication | Risk communication refers to the interactive process of exchanging information and opinions among individuals, groups, and institutions, which include natural or human-made hazards, such as flooding, wildfires, heatwaves, and droughts [6]. |

| Health communication | Health communication is a social activity that uses various methods to promote and popularize health science and technology knowledge related to human physical and mental health, advocate health science methods, and communicate health science ideas [7]. |

| Science communication | Science communication refers to the communication activity of popularizing scientific knowledge, promoting scientific ideas, and cultivating scientific spirit in the public through mass media [8]. |

| Political communication | Political communication is the operation process of the organic system of political information diffusion, acceptance, identification, and internalization within and among political communities, and it is the flow process of political information within and among political communities [9]. |

| Number | Cited Journals | Frequency | Cited Journals | Centrality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GLOBAL ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE | 267 | AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW | 0.10 |

| 2 | CLIMATIC CHANGE | 236 | JOURNAL OF PERSONALITY AND SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY | 0.09 |

| 3 | NATURE CLIMATE CHANGE | 206 | AMERICAN PSYCHOLOGIST | 0.09 |

| 4 | WIRES CLIMATE CHANGE | 190 | ENVIRONMENTAL RESEARCH LETTERS | 0.08 |

| 5 | SCIENCE COMMUNICATION | 159 | PUBLIC OPINION QUARTERLY | 0.08 |

| 6 | RISK ANALYSIS | 158 | AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PREVENTIVE MEDICINE | 0.08 |

| 7 | PUBLIC UNDERSTANDING OF SCIENCE | 152 | AMERICAN JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY | 0.08 |

| 8 | ENVIRONMENTAL COMMUNICATION | 136 | COMMUNICATION RESEARCH | 0.07 |

| 9 | JOURNAL OF ENVIRONMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY | 117 | ECOLOGICAL ECONOMICS | 0.07 |

| 10 | PLOS ONE | 114 | ADVANCES IN EXPERIMENTAL SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY | 0.07 |

| 11 | ENVIRONMENTS | 113 | ENVIRONMENT AND PLANNING A | 0.07 |

| 12 | PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCE USA | 112 | COMMUNICATION THEORY | 0.06 |

| 13 | SCIENCE | 107 | CLIMATIC CHANGE | 0.05 |

| 14 | ENVIRONMENT AND BEHAVIOR | 104 | ENVIRONMENTAL POLITICS | 0.05 |

| 15 | NATURE | 92 | PSYCHOLOGICAL BULLETIN | 0.05 |

| Cited References (High-Frequency) | Cited References (High betweenness Centrality) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Freq | Title | Centrality | Title |

| 28 | Meta-analyses of the determinants and outcomes of belief in climate change 10.1038/NCLIMATE2943 | 0.22 | Reorienting climate change communication for effective mitigation: forcing people to be green or fostering grass-roots engagement? 10.1177/1075547008328969 |

| 25 | Reflections on climate change communication research and practice in the second decade of the 21st century: what more is there to say? 10.1002/wcc.403 | 0.17 | Boomerang effects in science communication: How motivated reasoning and identity cues amplify opinion polarization about climate mitigation policies 10.1177/0093650211416646 |

| 17 | A public health frame arouses hopeful emotions about climate change 10.1007/s10584-012-0513-6 | 0.14 | The climate on cable: The nature and impact of global warming coverage on Fox News, CNN, and MSNBC 10.1177/1940161211425410 |

| 16 | Communicating climate change: history, challenges, process and future directions 10.1002/wcc.11 | 0.11 | The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks 10.1038/NCLIMATE1547 |

| 14 | The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks 10.1038/NCLIMATE1547 | 0.11 | Communicating climate change: Why frames matter for public engagement 10.3200/ENVT.51.2.12-23 |

| 14 | Cultural cognition of scientific consensus 10.1080/13669877.2010.511246 | 0.11 | The potential of microblogs for the study of public perceptions of climate change 10.1002/wcc.273 |

| 14 | Personally relevant climate change: The role of place attachment and local versus global message framing in engagement 10.1177/0013916511421196 | 0.09 | Meta-analyses of the determinants and outcomes of belief in climate change 10.1038/NCLIMATE2943 |

| 14 | Boomerang effects in science communication: How motivated reasoning and identity cues amplify opinion polarization about climate mitigation policies 10.1177/0093650211416646 | 0.09 | Consensus on consensus: a synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming 10.1088/1748-9326/11/4/048002 |

| 13 | The political divide on climate change: Partisan polarization widens in the US 10.1080/00139157.2016.1208995 | 0.08 | International trends in public perceptions of climate change over the past quarter century 10.1002/wcc.321 |

| 13 | “Fear won’t do it” promoting positive engagement with climate change through visual and iconic representations 10.1177/1075547008329201 | 0.07 | Social norms and efficacy beliefs drive the alarmed segment’s public-sphere climate actions 10.1038/NCLIMATE3025 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, M.; Long, R.; Yang, S.; Wang, X.; Chen, H. Evolution of the Knowledge Mapping of Climate Change Communication Research: Basic Status, Research Hotspots, and Prospects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11305. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811305

Wu M, Long R, Yang S, Wang X, Chen H. Evolution of the Knowledge Mapping of Climate Change Communication Research: Basic Status, Research Hotspots, and Prospects. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(18):11305. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811305

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Meifen, Ruyin Long, Shuhan Yang, Xinru Wang, and Hong Chen. 2022. "Evolution of the Knowledge Mapping of Climate Change Communication Research: Basic Status, Research Hotspots, and Prospects" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 18: 11305. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811305