Psychological Responses of Hungarian Students during the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analyses

2.4. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Correlation between the Mean of the Psychological Scale Total Scores (MAAS, WHO-5, PSS-14)

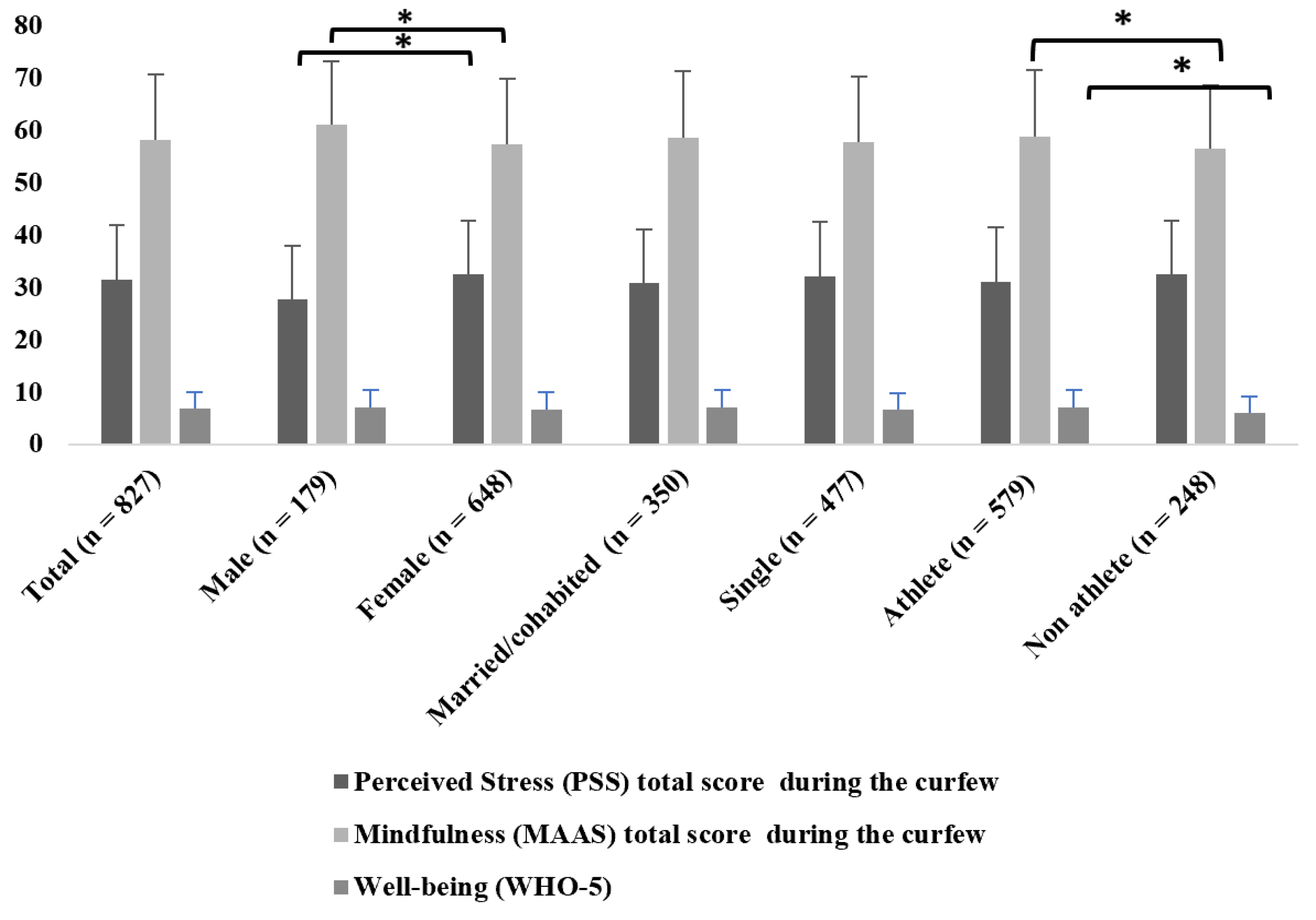

3.2. Differences between Perceived Stress (PSS-14), Trait Mindfulness (MAAS), and Well-Being (WHO-5) Total Scores Regarding Gender, Sporting Attitude, and Marital Status

3.2.1. Gender

3.2.2. Marital Status

3.2.3. Sporting Attitude

3.3. Differences of Subjective Mental and Physical Health Status, Assessment of Social Relations Regarding Gender, Sporting Attitude, and Marital Status

3.3.1. Gender

3.3.2. Marital Status

3.3.3. Sporting Attitude

3.4. Results Related to University Studies, Academic Work

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Docea, A.O.; Tsatsakis, A.; Albulescu, D.; Cristea, O.; Zlatian, O.; Vinceti, M.; Moschos, S.A.; Tsoukalas, D.; Goumenou, M.; Drakoulis, N.; et al. A new threat from an old enemy: Re-emergence of coronavirus (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2020, 45, 1631–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gradini, G.L. The World before and after COVID-19. Intellectual Reflections on Politics, Diplomacy and International Relations; Gardini, G.L., Ed.; European Institute of International Studies Press: Salamanca, Spain; Stockholm, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Government Decree No. 104/2021 of 5 March 2021 on the Temporary Tightening of Security Measures. 104/2021.III.5.Korm.Rendelet A Védelmi Intézkedlsek Ideiglenes Szigorításáról. Magyar Közlöny 104/2021.III.5.Korm.Rendelet A Védelmi Intézkedések Szigorításáról. Magyar Közlöny Lap- és Könyvkiadó Kft. 5 March 2021. Available online: https://net.jogtar.hu/jogszabaly?docid=A2100104.KOR×hift=20210419 (accessed on 28 July 2022).

- Aristovnik, A.; Keržič, D.; Ravšelj, D.; Tomaževič, N.; Umek, L. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Life of Higher Education Students: A Global Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, M.H.E.M.; Larson, L.R.; Sharaievska, I.; Rigolon, A.; McAnirlin, O.; Mullenbach, L.; Cloutier, S.; Vu, T.M.; Thomsen, J.; Reigner, N.; et al. Psychological impacts from COVID-19 among university students: Risk factors across seven states in the United States. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Sujan, S.H.; Tasnim, R.; Sikder, T.; Potenza, M.N.; van Os, J. Psychological responses during the COVID-19 outbreak among university students in Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0245083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garbóczy, S.; Szemán-Nagy, A.; Ahmad, M.S.; Harsányi, S.; Ocsenás, D.; Rekenyi, V.; Al-Tammemi, A.B.; Kolozsvári, L.R. Health anxiety, perceived stress, and coping styles in the shadow of the COVID-19. BMC Psychol. 2021, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gogoi, M.; Webb, A.; Pareek, M.; Bayliss, C.D.; Gies, L. University Students’ Mental Health and Well-Being during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Findings from the UniCoVac Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-García, G.; Ramos-Navas-Parejo, M.; de la Cruz-Campos, J.-C.; Rodríguez-Jiménez, C. Impact of COVID-19 on University Students: An Analysis of Its Influence on Psychological and Academic Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Hegde, S.; Son, C.; Keller, B.; Smith, A.; Sasangohar, F. Investigating Mental Health of US College Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Cross-Sectional Survey Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e22817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Yan, S.; Zong, Q.; Anderson-Luxford, D.; Song, X.; Lv, Z.; Lv, C. Mental health of college students during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 280, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roychowdhury, D. Mindfulness practice during COVID-19 crisis: Implications for confinement, physical inactivity, and sedentarism. Asian J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2021, 1, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonova, E.; Schlosser, K.; Pandey, R.; Kumari, V. Coping With COVID-19: Mindfulness-Based Approaches for Mitigating Mental Health Crisis. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 563417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Wherever You Go, There Are You; Hyperion: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeny, K.; Howell, J.L. Bracing Later and Coping Better: Benefits of Mindfulness During a Stressful Waiting Period. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 43, 1399–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeny, K.; Rankin, K.; Cheng, X.; Hou, L.; Long, F.; Meng, Y.; Azer, L.; Zhou, R.; Zhang, W. Flow in the time of COVID-19: Findings from China. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conversano, C.; Di Giuseppe, M.; Miccoli, M.; Ciacchini, R.; Gemignani, A.; Orrù, G. Mindfulness, Age and Gender as Protective Factors Against Psychological Distress During COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topp, C.W.; Østergaard, S.D.; Søndergaard, S.; Bech, P. The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: A systematic review of the literature. Psychother. Psychosom. 2015, 84, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bech, P. The Bech, Hamilton and Zung Scales for Mood Disorders: Screening and Listening; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bech, P.; Gudex, C.; Johansen, S. The WHO (Ten) Weil-Being Index: Validation in Diabetes. Psychother. Psychosom. 1996, 65, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanszky, E.; Thege, B.K.; Stauder, A.; Kopp, M. A Who Jól-Lét Kérdőív Rövidített (Wbi-5) Magyar Változatának Validálása a Hungarostudy 2002 Országos Lakossági Egészségfelmérés Alapján. Mentálhig. És Pszichoszomatika 2006, 7, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Tyrrell, D.A.; Smith, A.P. Negative life events, perceived stress, negative affect, and susceptibility to the common cold. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 64, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.-H. Review of the Psychometric Evidence of the Perceived Stress Scale. Asian Nurs. Res. 2012, 6, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauder, A.; Thege, B.K. Az Észlelt Stressz Kérdőív (Pss)Magyar Verziójának Jellemzői. Mentálhig. És Pszichoszomatika 2006, 7, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simor, P.; Petke, Z.; Köteles, F. Measuring pre-reflexive consciousness: The Hungarian validation of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS). Learn. Percept. 2013, 5 (Suppl. 2), 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, V.; Yadav, J.; Bajpai, L.; Srivastava, S. Perceived stress and psychological well-being of working mothers during COVID-19: A mediated moderated roles of teleworking and resilience. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2021, 43, 1290–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, B.; Gupta, R.; Pande, N. Self-esteem mediates the relationship between mindfulness and well-being. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2016, 94, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, M.; von Versen, C.; Hirschmüller, S.; Kubiak, T. Curb your neuroticism—Mindfulness mediates the link between neuroticism and subjective well-being. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2015, 80, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mettler, J.; Mills, D.J.; Heath, N.L. Problematic Gaming and Subjective Well-Being: How Does Mindfulness Play a Role? Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 18, 720–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, G. Understanding wellbeing and death obsession of young adults in the context of Coronavirus experiences: Mitigating the effect of mindful awareness. Death Stud. 2021, 46, 1923–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belen, H. Fear of COVID-19 and Mental Health: The Role of Mindfulness in During Times of Crisis. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 20, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ács, P.; Betlehem, J.; Laczkó, T.; Makai, A.; Morvay-Sey, K.; Pálvölgyi, Á.; Paár, D.; Prémusz, V.; Stocker, M. Változás a Magyar Lakosság Élet-És Munkakörülményeiben Kiemelten a Fizikai Aktivitás Changes the Living and Working Conditions of the Hungarian Population, with a Focus on Physical Activity and Sport Consuptipn Habits; Ács, P., Ed.; Pécsi Tudományegyetem: Pécs, Hungary, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Morvay-Sey, K.; Pálvölgyi, Á.; Prémusz, V.; Ács, P.; Stocker, M.; Makai, A.; Melczer, C.; Laczkó, T.; Szentei, A.; Paár, D. A COVID-19 Kijárási Korlátozás Első Hullámának Hatása a Magyar Felnőtt Lakosság Szubjektív Pszichés Mutatóira, Jóllétére, Fizikai Aktivitására És Sportolási Szokásaira (The Impact of the First Wave of COVID-19 Curfew on Subjective Psychological Indicators, Well-Being, Physical Activity and Sporting Habits of the Hungarian Adult Population). In Táplálkozás, Életmód és Testmozgás. (Nutrition, Lifestyle and Exercise); Antal, E., Pilling, R., Eds.; Táplálkozás, életmód és Testmozgás Platform Egyesület: Budapest, Hungary, 2020; pp. 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- Pálvölgyi, Á.; Makai, A.; Prémusz, V.; Trpkovici, M.; Ács, P.; Betlehem, J.; Morvay-Sey, K. A Preliminary Study on the Effect of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Sporting Behavior, Mindfulness and Well-Being. Health Probl. Civiliz. 2020, 14, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, C.; Pukánszky, J.; Kemény, L. Psychological Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Hungarian Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.G.; Van Der Boor, C. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and initial period of lockdown on the mental health and well-being of adults in the UK. BJPsych Open 2020, 6, e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hungarystudy 2013. Budapest 2013. Available online: http://www.hungarostudy.hu/index.php/2014-04-07-17-21-12/hungarostudy-2013 (accessed on 21 April 2020).

- Szabo, A.; Ábel, K.; Boros, S. Attitudes toward COVID-19 and stress levels in Hungary: Effects of age, perceived health status, and gender. Psychol. Trauma 2020, 12, 572–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowal, M.; Coll-Martín, T.; Ikizer, G.; Rasmussen, J.; Eichel, K.; Studzińska, A.; Koszałkowska, K.; Karwowski, M.; Najmussaqib, A.; Pankowski, D.; et al. Who is the Most Stressed During the COVID-19 Pandemic? Data From 26 Countries and Areas. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2020, 12, 946–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamonal-Limcaoco, S.; Montero-Mateos, E.; Lozano-López, M.T.; Maciá-Casas, A.; Matías-Fernández, J.; Roncero, C. Perceived stress in different countries at the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2021, 57, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Shen, B.; Zhao, M.; Wang, Z.; Xie, B.; Xu, Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: Implications and policy recommendations. Gen. Psychiatry 2020, 33, e100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisha Zubair, A.K.; Veronika, A. Mindfulness and Resilience as Predictors of Subjective Well-Being among University Students: A Cross Cultural Perspective. J. Behav. Sci. 2018, 28, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.-R.; Wang, K.; Yin, L.; Zhao, W.-F.; Xue, Q.; Peng, M.; Min, B.-Q.; Tian, Q.; Leng, H.-X.; Du, J.-L.; et al. Mental Health and Psychosocial Problems of Medical Health Workers during the COVID-19 Epidemic in China. Psychother. Psychosom. 2020, 89, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Hu, J.; Wei, N.; Wu, J.; Du, H.; Chen, T.; Li, R.; et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2020, 3, e203976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, C.; Ricci, E.; Biondi, S.; Colasanti, M.; Ferracuti, S.; Napoli, C.; Roma, P. A Nationwide Survey of Psychological Distress among Italian People during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Li, H.; Tian, S.; Yang, J.; Shao, J.; Tian, C. Psychological symptoms of ordinary Chinese citizens based on SCL-90 during the level I emergency response to COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 288, 112992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odriozola-González, P.; Planchuelo-Gómez, Á.; Irurtia, M.J.; de Luis-García, R. Psychological symptoms of the outbreak of the COVID-19 confinement in Spain. J. Health Psychol. 2022, 27, 825–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erus, S.M.; Deniz, M.E. The mediating role of emotional intelligence and marital adjustment in the relationship between mindfulness in marriage and subjective well-being. Pegem. Eğitim. Öğretim. Dergisi. 2020, 10, 317–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, E.M.; Corcoran, D.P.; O’Regan, G.; Keeley, H.; Cannon, M.; Carli, V.; Wasserman, C.; Hadlaczky, G.; Sarchiapone, M.; Apter, A.; et al. Physical activity in European adolescents and associations with anxiety, depression and well-being. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016, 26, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, M.; Houge Mackenzie, S.; Hodge, K.; Hargreaves, E.A.; Calverley, J.R.; Lee, C. Physical Activity and Psychological Well-Being During the COVID-19 Lockdown: Relationships with Motivational Quality and Nature Contexts. Front. Sports Act. Living 2021, 3, 637576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, K.C.; Danoff-Burg, S. Mindfulness and Health Behaviors: Is Paying Attention Good for You? J. Am. Coll. Health 2010, 59, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brajša-Žganec, A.; Merkaš, M.; Šverko, I. Quality of Life and Leisure Activities: How do Leisure Activities Contribute to Subjective Well-Being? Soc. Indic. Res. 2011, 102, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bize, R.; Johnson, J.A.; Plotnikoff, R.C. Physical activity level and health-related quality of life in the general adult population: A systematic review. Prev. Med. 2007, 45, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakır, Y.; Kangalgil, M. The Effect of Sport on the Level of Positivity and Well-Being in Adolescents Engaged in Sport Regularly. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2017, 5, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, S. Physical activity and mental health: Evidence is growing. World Psychiatry 2016, 15, 176–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos Fialho, P.M.; Spatafora, F.; Kühne, L.; Busse, H.; Helmer, S.M.; Zeeb, H.; Stock, C.; Wendt, C.; Pischke, C.R. Perceptions of Study Conditions and Depressive Symptoms During the COVID-19 Pandemic Among University Students in Germany: Results of the International COVID-19 Student Well-Being Study. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 674665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szlamka, Z.; Kiss, M.; Bernáth, S.; Kámán, P.; Lubani, A.; Karner, O.; Demetrovics, Z. Mental Health Support in the Time of Crisis: Are We Prepared? Experiences With the COVID-19 Counselling Programme in Hungary. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 655211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Végh, V.; Soltész-Várhelyi, K.; Pusztafalvi, H. Which Attitudes Helped the Academics to Overcome the Difficulties of Online Education During COVID-19? Sengupta, E., Blessinger, P., Eds.; New Student Literacies amid COVID-19: International Case Studies (Innovations in Higher Education Teaching and Learning); Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2021; Volume 41, pp. 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gender | Marital Status | Sporting Attitude | Stress about Technical Challenges of Online Learning | Stress about the Communication with Professors and Fellow Students | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Male | Fe-male | Statistics/p Value | Married/Cohabited | Single | Statistics/p Value | Athlete | Non-Athlete | Statistics/p Value | Yes | No | Statistics/p Value | Yes | No | Statistics/p Value | |

| Subjective physical health | 3.49 ± 0.98 | 3.49 ± 0.99 | 3.49 ± 0.99 | p = 0.929; Z = −0.089 | 3.47 ± 0.99 | 3.5± 0.98 | p = 0.601; Z = −0.524 | 3.61 ± 0.96 | 3.20 ± 0.96 | p < 0.001; Z = −5.623 | 3.33 ± 1.00 | 3.56 ± 0.96 | p < 0.005; Z = −2.798 | 3.28 ± 1.01 | 3.62 ± 0.94 | p < 0.001; Z = −4.702 |

| Subjective mental health | 3.01 ± 0.99 | 3.20 ± 0.99 | 2.96 ± 0.99 | p = 0.003; Z = −2.924 | 3.07 ± 1.00 | 2.97 ± 0.99 | p = 0.268; Z = −1.108 | 3.03 ± 1.01 | 2.98 ± 0.96 | p = 0.482; Z = −0.703 | 2.65 ± 0.99 | 3.15 ± 0.95 | p < 0.001; Z = −6.907 | 2.65 ± 0.96 | 3.25 ± 0.94 | p < 0.001; Z = −8.472 |

| Subjective rating of narrow the social relations | 3.83 ± 1.63 | 3.59 ± 1.35 | 3.90 ± 1.22 | p = 0.006; Z = −2.730 | 3.78 ± 1.23 | 3.87 ± 1.28 | p = 0.193; Z = −1.303 | 3.92 ± 1.24 | 3.62 ± 1.29 | p = 0.001, Z = −3.39 | 4.10 ± 1.13 | 3.72 ± 1.29 | p < 0.001; Z = −3.981 | 4.05 ± 1.17 | 3.69 ± 1.29 | p < 0.001; Z = −4.131 |

| PSS−14 total score | 31.4 ± 10.35 | 27.7 ± 10.19 | 32.5 ± 10.16 | p < 0.001; Z = −5.703 | 30.78 ± 10.30 | 31.9 ± 10.37 | p = 0.114; Z = −1.579 | 31.0 ± 10.35 | 32.43 ± 10.32 | p = 0.101; Z = −1.641 | 35.6 ± 9.74 | 29.5 ± 10.06 | p < 0.001; Z = −7.832 | 35.7 ± 9.81 | 28.5 ± 9.70 | p < 0.001; Z = −9.667 |

| MAAS total score | 58.0 ± 12.50 | 60.9 ± 12.10 | 57.3 ± 12.51 | p < 0.001; Z = −3.589 | 58.53 ± 12.64 | 57.7 ± 12.41 | p = 0.378; Z = −0.881 | 58.7 ± 12.68 | 56.51 ± 11.96 | p = 0.012, Z = −2.498 | 54.5 ± 12.64 | 59.6 ± 12.13 | p < 0.001; Z = −5.254 | 54.5 ± 12.61 | 60.5 ± 11.85 | p < 0.001; Z = −6.301 |

| WHO−5 score | 6.72 ± 3.24 | 6.92 ± 3.34 | 6.67 ± 3.34 | p = 0.339; Z = −0.957 | 6.94 ± 3.42 | 6.56 ± 3.09 | p = 0.217; Z = −1.235 | 7.03 ± 3.27 | 6.00 ± 3.04 | p < 0.001; Z = −4.349 | 5.72 ± 3.19 | 7.17 ± 3.16 | p < 0.001; Z = −6.125 | 5.77 ± 3.21 | 7.36 ± 3.10 | p < 0.001; Z = −6.990 |

| N | 827 | 179 | 648 | 350 | 477 | 579 | 248 | 255 | 572 | 333 | 494 | |||||

| What Do You Think about the Learning Process Is Like for Practical Subjects (Seminars, Practical Lessons) in Form of Distance Learning | In Case of Theoretical Lectures Do You Consider that Learning the Course Material Was Successful during Distance Learning | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| It Was Harder and Much More Difficult to Acquire Practical Knowledge because It Was Shared Theoretically what You Should Do in Practice | To Learn the Practice only in Theory Is much More Difficult, because It Requires Independent Practice and Training at Home | Practicing at Home Is an Unfulfillable Task (Because of the Lack of Staff and Equipment). | I Find Easier to Absolve the Practice-Based Courses this Way | DO Not Feel Any Changes Compared to Previous Experience (Personal Attendance) | Can Not Decide the Question | To Learn the Theoretical Subjects Is more Difficult Because It Takes More Time to Process The Material | Learning Online Is „Easier, because Online Recorded Lectures can Be Replayed | Do not Feel Any Changes Compared to Previous Experiences | Can Not Decide the Question | |

| Subjective physical health (mean ± sd) | 3.47 ± 0.97 | 3.40 ± 1.06 | 3.39 ± 0.91 | 3.75 ± 0.86 | 3.56 ± 0.957 | 3.65 ± 1.05 | 3.37 ± 0.98 | 3.54 ± 0.99 | 3.56 ± 0.93 | 3.72 ± 1.01 |

| Subjective mental health (mean ± sd) | 2.91 ± 0.968 | 2.93 ± 1.036 | 2.81 ± 0.97 | 3.54 ± 0.92 | 3.28 ± 1.01 | 3.26 ± 0.88 | 2.65 ± 0.95 | 3.32 ± 0.95 | 3.31 ± 0.93 | 3.07 ± 0.88 |

| Subjective rating of narrow the social relations (mean ± sd) | 4.031 ± 1.204 | 3.89 ± 1.155 | 4.01 ± 1..22 | 3.60 ± 1.287 | 3.34 ± 1.37 | 3.40 ± 1.36 | 4.12 ± 1.14 | 3.57 ± 1.30 | 3.63 ± 1.38 | 3.78 ± 1.11 |

| PSS-14 total score (mean ± sd) | 33.52 ± 9.35 | 31.63 ± 9.770 | 34.88 ± 10.42 | 25.63 ± 10.59 | 26.08 ± 10.24 | 27.77 ± 10.01 | 35.22 ± 9.43 | 28.45 ± 10.18 | 27.85 ± 10.04 | 31.40 ± 9.86 |

| MAAS total score (mean ± sd) | 58.044 ± 12.71 | 57.23 ± 12.530 | 56.07 ± 11.42 | 59.07 ± 12.11 | 59.94 ± 11.86 | 61.04 ± 14.11 | 56.01 ± 12.81 | 59.56 ± 12.09 | 59.86 ± 12.33 | 59.40 ± 11.46 |

| WHO-5 score (mean ± sd) | 6.51 ± 3.11 | 6.61 ± 3.070 | 5.67 ± 3.12 | 8.96 ± 3.32 | 7.49 ± 3.39 | 7.25 ± 3.09 | 5.67 ± 2.93 | 7.69 ± 3.25 | 7.62 ± 3.24 | 6.59 ± 3.02 |

| N | 294 | 168 | 141 | 52 | 100 | 72 | 353 | 245 | 160 | 69 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morvay-Sey, K.; Trpkovici, M.; Ács, P.; Paár, D.; Pálvölgyi, Á. Psychological Responses of Hungarian Students during the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11344. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811344

Morvay-Sey K, Trpkovici M, Ács P, Paár D, Pálvölgyi Á. Psychological Responses of Hungarian Students during the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(18):11344. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811344

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorvay-Sey, Kata, Melinda Trpkovici, Pongrác Ács, Dávid Paár, and Ágnes Pálvölgyi. 2022. "Psychological Responses of Hungarian Students during the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 18: 11344. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811344

APA StyleMorvay-Sey, K., Trpkovici, M., Ács, P., Paár, D., & Pálvölgyi, Á. (2022). Psychological Responses of Hungarian Students during the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11344. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811344