A Creative Approach to Knowledge Translation: The Use of Short Animated Film to Share Stories of Refugees and Mental Health

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Woven Threads Series

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative

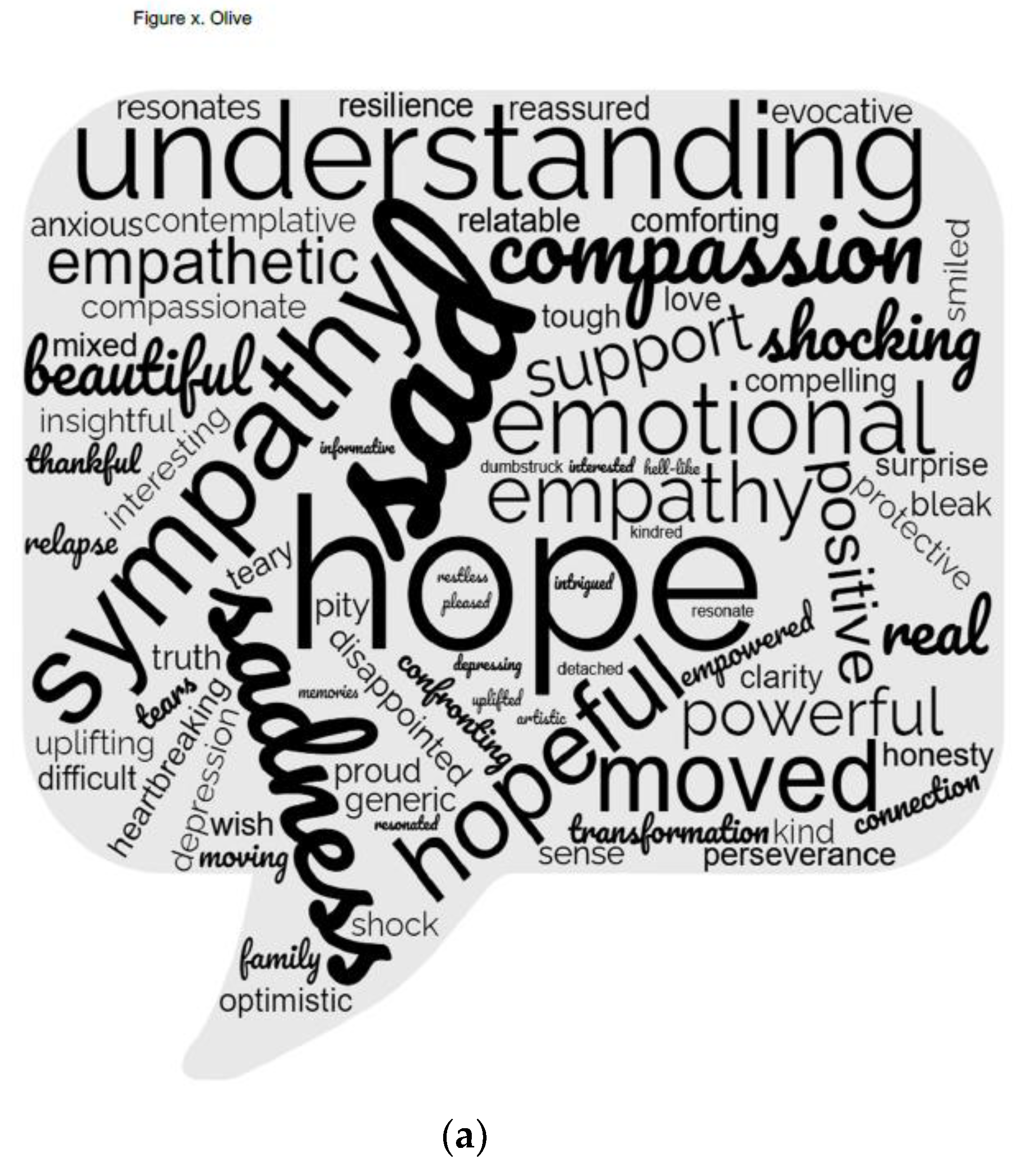

3.2. Qualitative

3.2.1. Film as a Knowledge Translation Strategy

3.2.2. Changing Perceptions and Inspiring Empathy

3.2.3. Enhancing Literacy and Potential for Social Change

3.2.4. The Power of Storytelling: Personal Stories Coming from Real People

3.2.5. Animated Film as Inspiring Hope and a Sense of Belonging

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boydell, K.M.; Hodgins, M.; Gladstone, B.M.; Stasiulis, E.; Belliveau, G.; Cheu, H.; Kontos, P.; Parsons, J. Arts-based health research and academic legitimacy: Transcending hegemonic conventions. Qual. Res. 2016, 16, 681–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, N.; Jacoby, S.; Williams, T.; Guerra, T.; Thomas, N.A.; Richmond, T.S. Digital animation as a method to disseminate research findings to the community using a community-based participatory approach. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2013, 51, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archibald, M.; Ambagtsheer, R.; Lawless, M.T.; Thompson, M.O.; Shultz, T.; Chehade, M.J.; Whiteway, L.; Sheppard, A.; Pinero-de Plaza, M.; Kitson, A.L. Co-designing evidence-based videos in health care: A case exemplar of developing creative knowledge translation ‘evidence-experience’ resources. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2021, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jager, A.; Fogarty, A.; Tewson, A.; Lenette, C.; Boydell, K.M. Digital storytelling in research: A systematic review. Qual. Rep. 2017, 22, 2548–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenette, C.; Brough, M.; Schweitzer, R.D.; Correa-Velez, I.; Murray, K.; Vromans, L. ‘Better than a pill’: Digital storytelling as a narrative process for refugee women. Media Pract. Educ. 2019, 20, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belliveau, G.; Lea, G. Research-Based Theatre: An Artistic Methodology; Intellect Books: Bristol, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, S.; Hartling, L.; O’Leary, K.; Archibald, M.; Klassen, T. Stories—A novel approach to transfer complex health information to parents: A qualitative study. Arts Health 2012, 4, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Hurwitz, B. Narrative Based Medicine: Dialogue and Discourse in Clinical Practice; BMJ Books: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ottoni, C.A.; Sims-Gould, J.; McKay, H.A. Video for knowledge translation: Engaging older adults in social and physical activity. Can. J. Aging 2020, 39, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann, S.E.; Merante, M.; Folb, B.L.; Burke, J.G. Is film as a research tool the future of public health? A review of study designs, opportunities, and challenges. Qual. Health Res. 2020, 30, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coughlan, H.; Quin, D.; O’Brien, K.; Healy, C.; Deacon, J.; Kavanaugh, N.; Humphries, N.; Clarke, M.C.; Cannon, M. Online mental health animations for young people: Qualitative empirical thematic analysis and knowledge transfer. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e21338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segal, E.A. Social Empathy: A Model Built on Empathy, Contextual Understanding, and Social Responsibility That Promotes Social Justice. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2011, 37, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Research; SAGE Publications Inc.: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- LaRocca, R.; Yost, J.; Dobbins, M.; Ciliska, D.; Butt, M. The effectiveness of knowledge translation strategies used in public health: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, K.; Bellis, M.A.; Isherwood, K.R.; Hughes, K.E. Perceptions of a short animated film on adverse childhood experiences: A mixed methods evaluation. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e050398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebert, C.; Dagenals, C.; McSween-Cadieux, E.; Ridde, V. Video as a public health knowledge transfer tool in Burkina Faso: A mixed evaluation comparing three narrative genres. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheba, G.; Moran, E.; Duran, N.; Jenders, R.A. Using amination as an information tool to advance health research literacy among minority participants. In Proceedings of the AMIA 2013 Annual Symposium, Washington, DC, USA, 16–20 November 2013; pp. 475–484. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, M.M.; Lucas, T.; Zachariah, M.; Feeley, T.; Tumiel Berhalter, L.; Kayler, L. A scoping review of animated video’s effect on individual health knowledge. Austin Med. Soc. 2021, 6, 1048. [Google Scholar]

- Lehoux, P.; Vachon, P.; Daudelin, G.; Hivon, M. How to summarize a 6000-word paper in a six-minute video clip. Healthc. Policy 2013, 8, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Film | # | Location | Sex | Australian Born | Education | Diagnosed Mental Health Issue | Self-Identify as Having a Mental Health Issue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hisham’s story | 374 | 48% regional/rural | 49% female | 49% | 33% postgraduate | 58% | 45% |

| Olive’s story | 275 | 48% regional/rural | 76% female | 85% | 35% postgraduate | 56% | 44% |

| Woven Threads Short Film: Refugee Short Film Responses | Agreed/Strongly Agreed |

|---|---|

| This film is a helpful way to challenge public misconceptions about refugees that lead to stigma and discrimination | 88% |

| I enjoyed watching the short film | 80% |

| Watching the film helped me understand myself or someone else better | 70% |

| I was left with a feeling of hopefulness after seeing the film | 64% |

| After seeing the film, I recognise that I or someone else might need help | 47% |

| Woven Threads Short Film: Mental Health Short Film Responses | Agreed/Strongly Agreed |

|---|---|

| This film is a helpful way to challenge public misconceptions about mental health that leads to stigma and discrimination | 89% |

| I enjoyed watching the short film | 83% |

| Watching the film helped me understand myself or someone else better | 82% |

| After seeing the film, I recognise that I or someone else might need help | 70% |

| I was left with a feeling of hopefulness after seeing the film | 66% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boydell, K.M.; Croguennec, J. A Creative Approach to Knowledge Translation: The Use of Short Animated Film to Share Stories of Refugees and Mental Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11468. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811468

Boydell KM, Croguennec J. A Creative Approach to Knowledge Translation: The Use of Short Animated Film to Share Stories of Refugees and Mental Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(18):11468. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811468

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoydell, Katherine M., and Joseph Croguennec. 2022. "A Creative Approach to Knowledge Translation: The Use of Short Animated Film to Share Stories of Refugees and Mental Health" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 18: 11468. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811468

APA StyleBoydell, K. M., & Croguennec, J. (2022). A Creative Approach to Knowledge Translation: The Use of Short Animated Film to Share Stories of Refugees and Mental Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11468. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811468