Multiple Long-Term Conditions (MLTC) and the Environment: A Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review Approach

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.5. Summarising and Analysis

3. Results

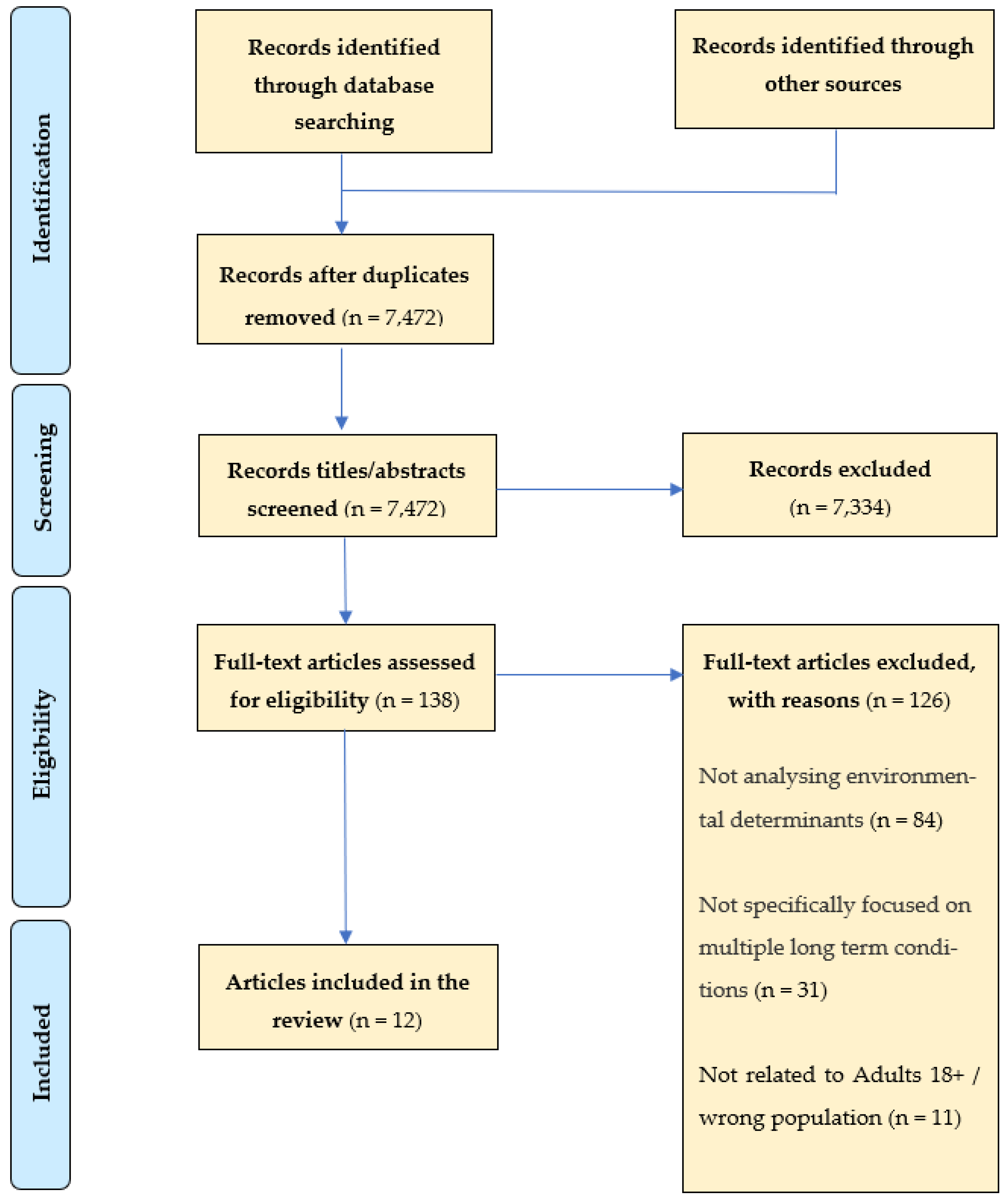

3.1. Screening Process

- -

- the article did not analyse environmental determinants;

- -

- the article did not specifically focus on the topic of multiple long-term conditions/multimorbidity;

- -

- the article was not related to the study population of adults aged 18+.

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.3. Summary of Environmental Factors

3.3.1. Built Urban Environment

3.3.2. The Built and Social Environments

3.3.3. The Social Environment

3.3.4. The Natural Environment

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Multiple Long-Term Conditions (Multimorbidity): A Priority for Global Health Research. The Academy of Medical Sciences. Available online: https://acmedsci.ac.uk/policy/policy-projects/multimorbidity (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- McPhail, S.M. Multimorbidity in chronic disease: Impact on health care resources and costs. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2016, 9, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassell, A.; Edwards, D.; Harshfield, A.; Rhodes, K.; Brimicombe, J.; Payne, R.; Griffin, S. The epidemiology of multimorbidity in primary care: A retrospective cohort study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 68, e245–e251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokes, J.; Guthrie, B.; Mercer, S.; Rice, N.; Sutton, M. Multimorbidity combinations, costs of hospital care and potentially preventable emergency admissions in England: A cohort study. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, P.; Woolford, S.J.; Patel, H.P. Multi-Morbidity and Polypharmacy in Older People: Challenges and Opportunities for Clinical Practice. Geriatrics 2020, 5, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakib, M.N.; Shooshtari, S.; St John, P.; Menec, V. The prevalence of multimorbidity and associations with lifestyle factors among middle-aged Canadians: An analysis of Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging data. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingston, A.; Robinson, L.; Booth, H.; Knapp, M.; Jagger, C. Projections of multi-morbidity in the older population in England to 2035: Estimates from the Population Ageing and Care Simulation (PACSim) model. Age Ageing 2018, 47, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson-Stuttard, J.; Ezzati, M.; Gregg, E.W. Multimorbidity—A defining challenge for health systems. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e599–e600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, I.S.S.; Azcoaga-Lorenzo, A.; Akbari, A.; Davies, J.; Hodgins, P.; Khunti, K.; Kadam, U.; Lyons, R.; McCowan, C.; Mercer, S.W.; et al. Variation in the estimated prevalence of multimorbidity: Systematic review and meta-analysis of 193 international studies. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e057017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiers, G.; Boulton, E.; Corner, L.; Craig, D.; Parker, S.; Todd, C.; Hanratty, B. What Matters to People with Multiple Long-Term Conditions and Their Carers? Postgrad. Med. J. 2021. Available online: https://pmj.bmj.com/content/early/2021/12/17/postgradmedj-2021-140825 (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Guthrie, B.; Payne, K.; Alderson, P.; McMurdo, M.E.T.; Mercer, S.W. Adapting clinical guidelines to take account of multimorbidity. BMJ 2012, 345, e6341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Making Sense of the Evidence: Multiple Long-Term Conditions (Multimorbidity). NIHR Evidence. 2021. Available online: https://evidence.nihr.ac.uk/collection/making-sense-of-the-evidence-multiple-long-term-conditions-multimorbidity/ (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- Vallesi, S.; Tuson, M.; Davies, A.; Wood, L. Multimorbidity among People Experiencing Homelessness—Insights from Primary Care Data. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knies, G.; Kumari, M. Multimorbidity is associated with the income, education, employment and health domains of area-level deprivation in adult residents in the UK. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onder, G.; Bernabei, R.; Vetrano, D.L.; Palmer, K.; Marengoni, A. Facing multimorbidity in the precision medicine era. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2020, 190, 111287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, K.R.; Corvalán, C.F.; Kjellström, T. How Much Global Ill Health Is Attributable to Environmental Factors? Epidemiology 1999, 10, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Public Health England. Spatial Planning for Health: An Evidence Resource for Planning and Designing Healthier Places; 69p. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/spatial-planning-for-health-evidence-review (accessed on 26 June 2022).

- Pearce, J.R.; Richardson, E.A.; Mitchell, R.A.; Shortt, N.K. Environmental justice and health: The implications of the socio-spatial distribution of multiple environmental deprivation for health inequalities in the United Kingdom. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2010, 35, 522–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prüss-Ustün, A.; Wolf, J.; Corvalán, C.; Neville, T.; Bos, R.; Neira, M. Diseases due to unhealthy environments: An updated estimate of the global burden of disease attributable to environmental determinants of health. J. Public Health 2017, 39, 464–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinter-Wollman, N.; Jelić, A.; Wells, N.M. The impact of the built environment on health behaviours and disease transmission in social systems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2018, 373, 20170245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Concepts Series 11—Glasgow Centre for Population Health. Available online: https://www.gcph.co.uk/publications/472_concepts_series_11-the_built_environment_and_health_an_evidence_review?aq=breast (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- Singer, L.; Green, M.; Rowe, F.; Ben-Shlomo, Y.; Morrissey, K. Social Determinants of Multimorbidity and Multiple Functional Limitations among the Ageing Population of England, 2002–2015. SSM—Popul Health. 2019. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6551564/ (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.; Colquhoun, H.; Kastner, M.; Levac, D.; Ng, C.; Sharpe, J.P.; Wilson, K.; et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2016, 16, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dambha-Miller, H.; Simpson, G.; Hobson, L.; Roderick, P.; Little, P.; Everitt, H.; Santer, M. Integrated primary care and social services for older adults with multimorbidity in England: A scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| MeSH and Free Text Search Terms | Databases Searched | Filters/Refined by | Number of Sources Identified |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) MESH: Multimorbidity (or equivalent on database) FREE TEXT: MLTC OR MLT-C OR MLTC-M OR MLTM OR Multiple Long Term Conditions OR Multimorbidity OR Multimorbid OR Multimorbidities OR Co-morbid OR Multiple Conditions (2) MESH: Environmental (or equivalent on your database) FREE TEXT: Green OR open space OR Housing OR Mobility OR Air pollution OR Air Quality OR noise OR water quality | Medline | All dates searched. Language: restricted to English/English Language. | 550 |

| Embase | All dates searched. Language: restricted to English. | 1031 | |

| Cochrane Library | All dates searched. Language: restricted to English. | 5092 | |

| Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) | All dates searched. Language: restricted to English. | 2173 | |

| ‘MULTIMORBIDITY’ AND ‘ENVIRONMENTAL DETERMINANTS’ doctype:1 (free text AND mesh terms specific to BASE database) = 98 MULTIPLE LONG TERM CONDITIONS AND ‘ENVIRONMENTAL DETERMINANTS’ doctype:1 (free text AND mesh terms specific to BASE database) = 129 | BASE | All dates searched. Language: restricted to English. Entire document. | 227 |

| Manual searches/references/ expert input | 6 | ||

| Total = 9079 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dambha-Miller, H.; Cheema, S.; Saunders, N.; Simpson, G. Multiple Long-Term Conditions (MLTC) and the Environment: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11492. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811492

Dambha-Miller H, Cheema S, Saunders N, Simpson G. Multiple Long-Term Conditions (MLTC) and the Environment: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(18):11492. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811492

Chicago/Turabian StyleDambha-Miller, Hajira, Sukhmani Cheema, Nile Saunders, and Glenn Simpson. 2022. "Multiple Long-Term Conditions (MLTC) and the Environment: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 18: 11492. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811492

APA StyleDambha-Miller, H., Cheema, S., Saunders, N., & Simpson, G. (2022). Multiple Long-Term Conditions (MLTC) and the Environment: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11492. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811492