Individual and Work-Related Predictors of Exhaustion in East and West Germany

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. The Definition and Identification of Exhaustion and Burnout

2.2. Constant Availability and Technostress as Modern Side Effects

2.3. Different Occupational Environments in East and West Germany

2.4. Aims of the Study

- (1)

- To examine the associations of work-related and individual predictors with exhaustion.

- (2)

- To examine whether associations between work-related and individual predictors with exhaustion differed between East and West Germany.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Exhaustion

3.2.2. Communication Load

3.2.3. Constant Availability

3.2.4. Work–Life Balance

3.2.5. Sociodemographic Aspects

3.3. Analyses

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Results

4.2. Predictors of Exhaustion in Germany

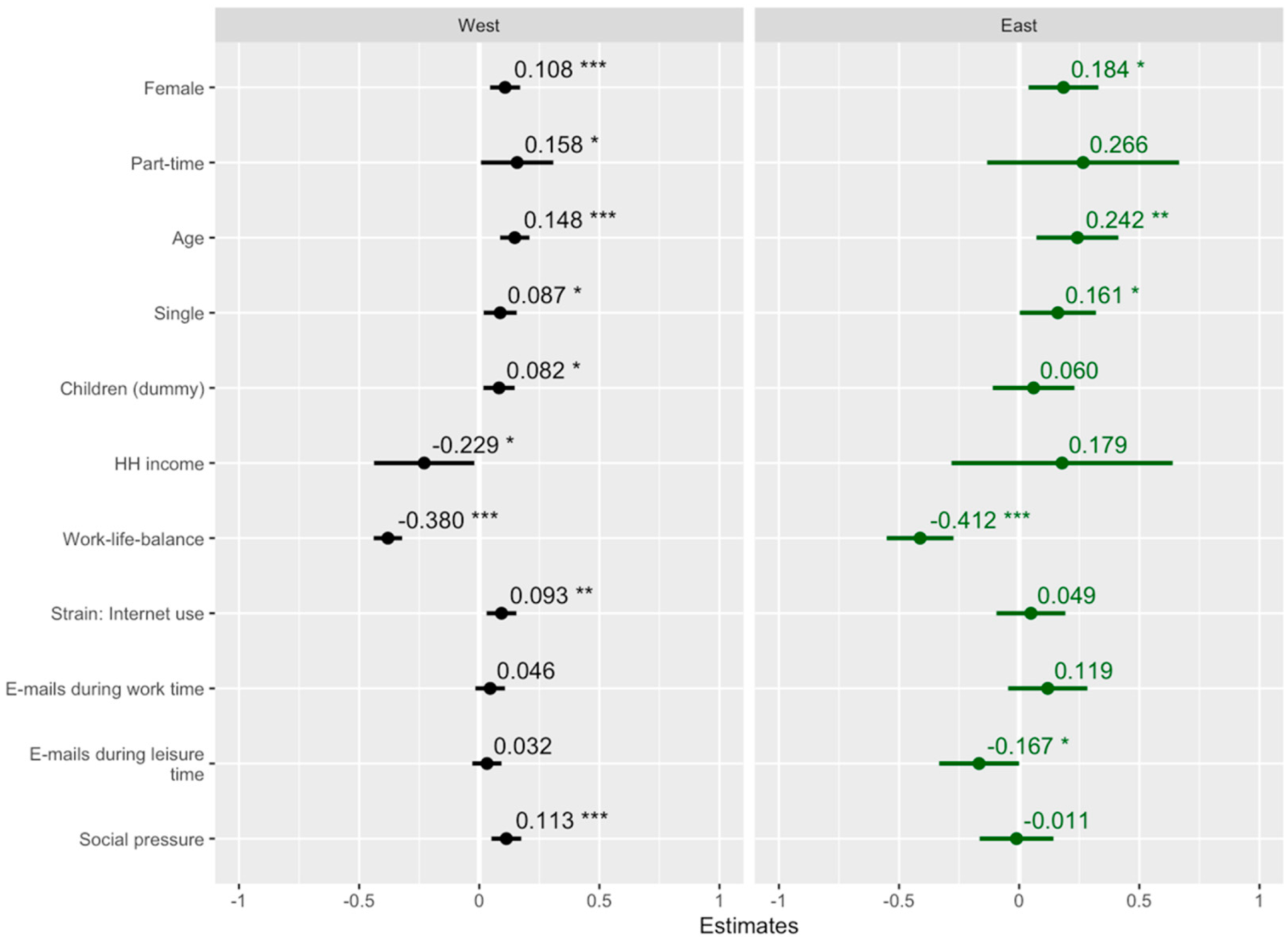

4.3. Predictors in East and West Germany

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ragu-Nathan, T.S.; Tarafdar, M.; Ragu-Nathan, B.S.; Tu, Q. The Consequences of Technostress for End Users in Organizations: Conceptual Development and Empirical Validation. Inf. Syst. Res. 2008, 19, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninaus, K.; Diehl, S.; Terlutter, R. Employee Perceptions of Information and Communication Technologies in Work Life, Perceived Burnout, Job Satisfaction and the Role of Work-Family Balance. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 136, 652–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenberger, H.J. Staff Burn-Out. J. Soc. Issues 1974, 30, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoman, Y.; El May, E.; Marca, S.C.; Wild, P.; Bianchi, R.; Bugge, M.D.; Caglayan, C.; Cheptea, D.; Gnesi, M.; Godderis, L.; et al. Predictors of Occupational Burnout: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuerhahn, N.; Kühnel, J.; Kudielka, B.M. Interaction Effects of Effort–Reward Imbalance and Overcommitment on Emotional Exhaustion and Job Performance. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2012, 19, 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahola, K.; Pulkki-Raback, L.; Kouvonen, A.; Rossi, H.; Aromaa, A.; Lonnyvist, J. Burnout and Behavior-Related Health Risk Factors Results from the Population-Based Finnish Health 2000 Study. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2012, 54, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, D.M.; Seidler, A.; Nübling, M.; Latza, U.; Brähler, E.; Klein, E.M.; Wiltink, J.; Michal, M.; Nickels, S.; Wild, P.S.; et al. Associations of Fatigue to Work-Related Stress, Mental and Physical Health in an Employed Community Sample. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dam, A. A Clinical Perspective on Burnout: Diagnosis, Classification, and Treatment of Clinical Burnout. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2021, 30, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakh-Pines, A.; Aronson, E.; Kafry, D. Burnout: From Tedium to Personal Growth; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1981; ISBN 0029253500. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C. Burnout: A Multidimensional Perspective. In Professional Burnout: Recent Developments in Theory and Research; Series in Applied Psychology: Social Issues and Questions; Taylor & Francis: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1993; pp. 19–32. ISBN 1-56032-262-4. [Google Scholar]

- WHO ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics, Version 02/2022. 2022. Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Kristensen, T.S.; Borritz, M.; Villadsen, E.; Christensen, K.B. The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: A New Tool for the Assessment of Burnout. Work Stress 2005, 19, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, K.; Brinkmann, U.; Engel, T. Differenz in Der Einheit: Ein Ostdeutscher Sonderweg Im Betrieblichen Gesundheitsschutz; WSI Mitteilungen: Düsseldorf, Germany; Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaftliches Institut: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2010; pp. 365–373. [Google Scholar]

- Ketzmerick, T. The Transformation of the East German Labour Market: From Short-Term Responses to Long-Term Consequences. Hist. Soc. Res. 2016, 41, 229–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutel, M.E.; Krakau, L.; Schmutzer, G.; Brähler, E. Somatic Symptoms in the Eastern and Western States of Germany 30 years after Unification: Population-Based Survey Analyses. J. Psychosom. Res. 2021, 147, 110535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C. Burned-Out. Hum. Relat. 1976, 5, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Greenglass, E.R. Introduction to Special Issue on Burnout and Health. Psychol. Health 2001, 16, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO ICD-10 Version: 2016. 2016. Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse10/2016/en#/Z73.0 (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Leiter, M.P. Maslach Burnout Inventory: Third Edition. In Evaluating Stress: A Book of Resources; Scarecrow Education: Lanham, MD, USA, 1997; pp. 191–218. ISBN 0-8108-3231-3. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, A.M.; Schmalbach, B.; Zenger, M.; Brähler, E.; Hinz, A.; Kruse, J.; Kampling, H. Measuring Physical, Cognitive, and Emotional Aspects of Exhaustion with the BOSS II-Short Version—Results from a Representative Population-Based Study in Germany. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuebling, M.; Hegewald, J.; Starke, K.R.; Lincke, H.-J.; Jankowiak, S.; Liebers, F.; Latza, U.; Letzel, S.; Riechmann-Wolf, M.; Gianicolo, E.; et al. The Gutenberg Health Study: A Five-Year Prospective Analysis of Psychosocial Working Conditions Using COPSOQ (Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire) and ERI (Effort-Reward Imbalance). BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg-Beckhoff, G.; Nielsen, G.; Larsen, E.L. Use of Information Communication Technology and Stress, Burnout, and Mental Health in Older, Middle-Aged, and Younger Workers—Results from a Systematic Review. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health 2017, 23, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinecke, L.; Aufenanger, S.; Beutel, M.E.; Dreier, M.; Quiring, O.; Stark, B.; Wölfling, K.; Müller, K.W. Digital Stress over the Life Span: The Effects of Communication Load and Internet Multitasking on Perceived Stress and Psychological Health Impairments in a German Probability Sample. Media Psychol. 2017, 20, 90–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, S.; Stokols, D. Psychological and Health Outcomes of Perceived Information Overload. Environ. Behav. 2012, 44, 737–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, M.; Pati, S. Assoc Comp Machinery Technostress Creators and Burnout: A Job Demands-Resources Perspective. In Proceedings of the 2018 ACM SIGMIS Conference on Computers and People Research, Niagara Falls, NY, USA, 18–20 June 2018; pp. 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakh-Pines, A. The Burnout Measure, Short Version. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2005, 12, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocyba, H.; Voswinkel, S. Krankheitsverleugnung: Betriebliche Gesundheitskulturen Und Neue Arbeitsformen; Hans-Böckler-Stiftung: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, E.M.; Brähler, E.; Dreier, M.; Reinecke, L.; Müller, K.W.; Schmutzer, G.; Wölfling, K.; Beutel, M.E. The German Version of the Perceived Stress Scale—Psychometric Characteristics in a Representative German Community Sample. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cohen, S.; Janicki-Deverts, D.; Miller, G.E. Psychological Stress and Disease. JAMA 2007, 298, 1685–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberti, J.W.; Harrington, L.N.; Storch, E.A. Further Psychometric Support for the 10-Item Version of the Perceived Stress Scale. J. Coll. Couns. 2006, 9, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-8058-5924-9. [Google Scholar]

- Syrek, C.; Bauer-Emmel, C.; Antoni, C. Entwicklung Und Validierung Der Trierer Kurzskala Zur Messung von Work-Life Balance (TKS-WLB). Diagnostica 2011, 57, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Total (n = 1065) | West (n = 896) | East (n = 169) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N | %/Mean | SD | N | %/Mean | SD | N | %/Mean | SD | Significance Test 1 |

| Sociodemographic factors | ||||||||||

| Sex (women) 2 | 535 | 50.20% | 448 | 50% | 87 | 51.50% | χ2 = 0.072 | |||

| Work hours (part-time) 2 | 261 | 24.50% | 230 | 25.70% | 31 | 18.30% | χ2 = 3.739 * | |||

| Household (no partner) 2 | 521 | 48.90% | 446 | 49.80% | 75 | 44.40% | χ2 = 1.449 | |||

| Children (yes) 2 | 708 | 66.50% | 590 | 65.80% | 118 | 69.80% | χ2 = 0.837 | |||

| Age | 1065 | 42.650 | 11.369 | 896 | 42.542 | 11.392 | 169 | 43.219 | 11.259 | F = 0.503 |

| Household income (EUR) | 1065 | 2784.108 | 1164.631 | 896 | 2855.162 | 1173.319 | 169 | 2407.396 | 1042.375 | F = 21.42 *** |

| Psychological factors | ||||||||||

| Exhaustion | 1065 | 29.131 | 19.803 | 896 | 29.667 | 19.973 | 169 | 26.294 | 18.674 | F = 4.136 ** |

| Work–life balance | 1065 | 70.043 | 21.894 | 896 | 69.847 | 21.905 | 169 | 71.082 | 21.873 | F = 0.452 |

| ICT use | ||||||||||

| Strain: Internet use | 1065 | 0.585 | 0.945 | 896 | 0.571 | 0.938 | 169 | 0.657 | 0.982 | F = 1.16 |

| E-mails during work time | 1065 | 4.917 | 10.038 | 896 | 5.169 | 10.608 | 169 | 3.586 | 6.053 | F = 3.543 * |

| E-mails during leisure time | 1065 | 1.458 | 5.181 | 896 | 1.519 | 5.548 | 169 | 1.136 | 2.427 | F = 0.776 |

| Social pressure | 1065 | 34.217 | 30.392 | 896 | 33.182 | 30.056 | 169 | 39.701 | 31.646 | F = 6.576 ** |

| Item | t | r | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction with job | −11.732 | −0.323 | <0.001 |

| Perceived self-efficacy | −10.669 | −0.296 | <0.001 |

| Perceived helplessness | 27.087 | 0.619 | <0.001 |

| Total | West | East | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | p3 | Mean | SD | p3 | Mean | SD | p3 | |

| Region | <0.05 | ||||||||

| West | 29.785 | 19.801 | |||||||

| East | 26.543 | 19.105 | |||||||

| Sex | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Male | 25.811 | 18.779 | 26.769 | 19.055 | 20.543 | 16.292 | |||

| Female | 32.553 | 20.043 | 32.742 | 20.088 | 31.654 | 19.894 | |||

| Household | <0.05 | <0.05 | 0.129 | ||||||

| Partner | 27.761 | 18.883 | 28.456 | 19.156 | 24.469 | 17.247 | |||

| No partner | 30.550 | 20.340 | 30.911 | 20.281 | 28.576 | 20.650 | |||

| Children | <0.05 | <0.05 | 0.768 | ||||||

| Yes | 30.802 | 20.108 | 28.877 | 19.553 | 26.259 | 18.986 | |||

| No | 28.443 | 19.473 | 31.504 | 20.178 | 27.105 | 19.469 |

| Factor Score Exhaustion | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Estimates | std. β | std. CI | p 5 | std. p 5 |

| (Intercept) | 52.35 *** | −0.10 | −0.36–0.17 | <0.001 | 0.479 |

| East | −3.47 * | −0.17 | −0.32–−0.03 | 0.020 | 0.020 |

| Female | 4.96 *** | 0.25 | 0.14–0.36 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Part-time (ref = full-time) | 2.95 * | 0.15 | 0.01–0.29 | 0.037 | 0.033 |

| Age | 0.28 *** | 0.16 | 0.10–0.22 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Household (ref = partner) | 3.79 ** | 0.19 | 0.07–0.32 | 0.003 | 0.003 |

| Children (ref = no children) | 3.49 ** | 0.17 | 0.05–0.30 | 0.006 | 0.007 |

| Household income (log) | −2.54 | −0.17 | −0.37–0.02 | 0.070 | 0.079 |

| Work–life balance | −0.35 *** | −0.39 | −0.44–−0.33 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Strain: Internet use | 1.66 ** | 0.08 | 0.02–0.14 | 0.006 | 0.006 |

| E-mails during work time | 0.09 | 0.05 | −0.01–0.10 | 0.112 | 0.112 |

| E-mails during leisure time | 0.08 | 0.02 | −0.03–0.08 | 0.462 | 0.461 |

| Social pressure | 0.06 ** | 0.10 | 0.04–0.15 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Observations | 1065 | ||||

| R2/R2 adjusted | 0.262/0.253 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Braunheim, L.; Otten, D.; Kasinger, C.; Brähler, E.; Beutel, M.E. Individual and Work-Related Predictors of Exhaustion in East and West Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11533. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811533

Braunheim L, Otten D, Kasinger C, Brähler E, Beutel ME. Individual and Work-Related Predictors of Exhaustion in East and West Germany. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(18):11533. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811533

Chicago/Turabian StyleBraunheim, Lisa, Daniëlle Otten, Christoph Kasinger, Elmar Brähler, and Manfred E. Beutel. 2022. "Individual and Work-Related Predictors of Exhaustion in East and West Germany" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 18: 11533. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811533