Interventions by Caregivers to Promote Motor Development in Young Children, the Caregivers’ Attitudes and Benefits Hereof: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Aim

3. Methods

3.1. Identification of Article

3.2. Search Strategy

3.3. Screening and Selection of Articles

3.4. Extraction and Interpretation of Data

4. Results

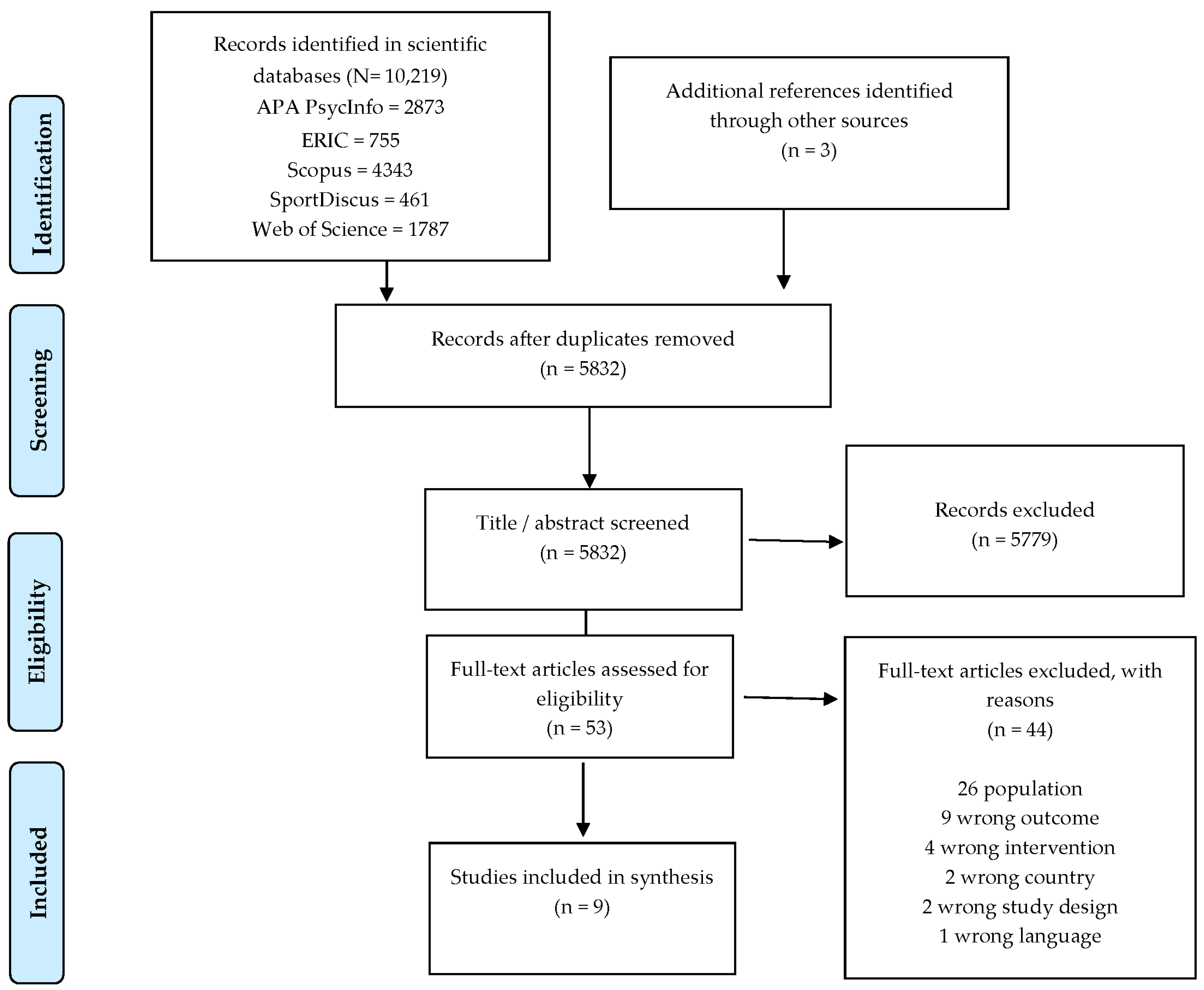

4.1. Number of Included Studies

4.2. Description of the Included Studies

4.3. Summary of Results

4.3.1. Impact of Interventions on the Young Child’s Motor Development

4.3.2. Caregivers’ Attitudes and Benefits of the Interventions

5. Discussion

5.1. Methodological Considerations Relating to the Articles Included in this Review

5.2. Methodological Considerations of This Review

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Logan, S.W.; Robinson, L.E.; Getchell, N.; Webster, E.K.; Liang, L.-Y.; Golden, D. Relationship Between Motor Competence and Physical Activity: A Systematic Review. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2014, 85, A14. [Google Scholar]

- Okely, A.D.; Booth, M.L.; Patterson, J.W. Relationship of Cardiorespiratory Endurance to Fundamental Movement Skill Proficiency among Adolescents. Pediatric Exerc. Sci. 2001, 13, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, J.R. Effects of physical activity on children’s executive function: Contributions of experimental research on aerobic exercise. Dev. Rev. 2010, 30, 331–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piek, J.P.; Dawson, L.; Smith, L.M.; Gasson, N. The role of early fine and gross motor development on later motor and cognitive ability. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2008, 27, 668–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, H.C.; Hill, E.L. Review: The impact of motor development on typical and atypical social cognition and language: A systematic review. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2014, 19, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenzie, T.L.; Sallis, J.F.; Broyles, S.L.; Zive, M.M.; Nader, P.R.; Berry, C.C.; Brennan, J.J. Childhood Movement Skills: Predictors of Physical Activity in Anglo American and Mexican American Adolescents? Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2002, 73, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, L.M.; Van Beurden, E.; Morgan, P.J.; Brooks, L.O.; Beard, J.R. Childhood Motor Skill Proficiency as a Predictor of Adolescent Physical Activity. J. Adolesc. Health 2009, 44, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandorpe, B.; Vandendriessche, J.; Vaeyens, R.; Pion, J.; Matthys, S.; Lefevre, J.; Philippaerts, R.; Lenoir, M. Relationship between sports participation and the level of motor coordination in childhood: A longitudinal approach. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2011, 15, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piek, J.P.; Baynam, G.B.; Barrett, N.C. The relationship between fine and gross motor ability, self-perceptions and self-worth in children and adolescents. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2006, 25, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, R.A.; Piek, J.P. Psychosocial implications of poor motor coordination in children and adolescents. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2001, 20, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, T.P.; Pant, S.W.; Ammitzbøll, J. Sundhedsplejerskers Bemærkninger til Motorisk Udvikling i det Første Leveår. Temarapport. Børn født i 2017; Databasen Børns Sundhed og Statens Institut for Folkesundhed, SDU: København, Danmark, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brixval, C.S.; Svendsen, M.; Holstein, B.E. Årsrapport for Børn Indskolet i 2009/10 og 2010/11 fra Databasen Børns Sundhed: Motoriske Vanskeligheder; Syddansk Universitet. Statens Institut for Folkesundhed: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pant, S.W.; Pedersen, T.P. Sundhedsprofil for Børn Født i 2016 fra Databasen Børns Sundhed; Databasen Børns Sundhed og Statens Institut for Folkesundhed, SDU: København, Danmark, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Riethmuller, A.M.; Jones, R.A.; Okely, A.D. Efficacy of Interventions to Improve Motor Development in Young Children: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics 2009, 124, e782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldman, S.L.C.; Jones, R.A.; Okely, A.D. Efficacy of gross motor skill interventions in young children: An updated systematic review. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2016, 2, e000067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venetsanou, F.; Kambas, A. Environmental Factors Affecting Preschoolers’ Motor Development. Early Child. Educ. J. 2009, 37, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.; van Jaarsveld, C.H.M.; Llewellyn, C.H.; Fildes, A.; López Sánchez, G.F.; Wardle, J.; Fisher, A. Genetic and Environmental Influences on Developmental Milestones and Movement: Results from the Gemini Cohort Study. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2017, 88, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachry, A.H.; Kitzmann, K.M. Caregiver Awareness of Prone Play Recommendations. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2011, 65, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavousipor, S.; Rassafiani, M.; Gabbard, C.; Pourahmad, S.; Hosseini, S.A.; Soleimani, F.; Ebadi, A. Influence of the home affordances on motor skills in 3- to 18-month-old Iranian children. Early Child Dev. Care 2021, 191, 2626–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathways. Tools to Maximize Child Development. Available online: https://pathways.org/free-tools-maximize-child-development/ (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Dudek-Shriber, L.; Zelazny, S. The effects of prone positioning on the quality and acquisition of developmental milestones in four-month-old infants. Pediatric Phys. Ther. 2007, 19, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y.-L.; Liao, H.-F.; Chen, P.-C.; Hsieh, W.-S.; Hwang, A.-W. The Influence of Wakeful Prone Positioning on Motor Development During the Early Life. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatrics 2008, 29, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewitt, L.; Kerr, E.; Stanley, R.M.; Okely, A.D. Tummy Time and Infant Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics 2020, 145, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines on Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour and Sleep for Children under 5 Years of Age; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Wick, K.; Leeger-Aschmann, C.S.; Monn, N.D.; Radtke, T.; Ott, L.V.; Rebholz, C.E.; Cruz, S.; Gerber, N.; Schmutz, E.A.; Puder, J.J.; et al. Interventions to Promote Fundamental Movement Skills in Childcare and Kindergarten: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 2045–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, A.J.; Redsell, S.A.; Glazebrook, C. Motor Development Interventions for Preterm Infants: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20160147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Implement. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, R.S.; Mendelsohn, A.L.; Yin, H.S.; Tomopoulos, S.; Gross, M.B.; Scheinmann, R.; Messito, M.J. Randomized controlled trial of an early child obesity prevention intervention: Impacts on infant tummy time. Obesity 2017, 25, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobo, M.A.; Galloway, J.C. Enhanced Handling and Positioning in Early Infancy Advances Development Throughout the First Year. Child Dev. 2012, 83, 1290–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-M.; Galloway, J.C. Early Intensive Postural and Movement Training Advances Head Control in Very Young Infants. Phys. Ther. 2012, 92, 935–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendres-Smith, A.E.; Borrero, J.C.; Castillo, M.I.; Davis, B.J.; Becraft, J.L.; Hussey-Gardner, B. Tummy time without the tears: The impact of parent positioning and play: Infant Behavior During Tummy Time. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 2020, 53, 2090–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldman, S.L.C.; Okely, A.D.; Jones, R.A. Promoting gross motor skills in toddlers: The active beginnings pilot cluster randomized trial. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2015, 121, 857–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaub, S.; Ramseier, E.; Neuhauser, A.; Burkhardt, S.C.A.; Lanfranchi, A. Effects of home-based early intervention on child outcomes: A randomized controlled trial of Parents as Teachers in Switzerland. Early Child. Res. Q. 2019, 48, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendelsohn, A.L.; Valdez, P.T.; Flynn, V.; Foley, G.M.; Berkule, S.B.; Tomopoulos, S.; Fierman, A.H.; Tineo, W.; Dreyer, B.P. Use of videotaped interactions during pediatric well-child care: Impact at 33 months on parenting and on child development. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatrics 2007, 28, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewitt, L.; Stephens, S.; Spencer, A.; Stanley, R.M.; Okely, A.D. Weekly group tummy time classes are feasible and acceptable to mothers with infants: A pilot cluster randomized controlled trial. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2020, 6, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, C.F.; Rindler, D.; Leverone, B. Moving into tummy time, together: Touch and transitions aid parent confidence and infant development. Infant. Ment. Health J. 2019, 40, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felzer-Kim, I.T.; Erickson, K.; Adkins, C.; Hauck, J.L. Wakeful Prone “Tummy Time” During Infancy: How Can We Help Parents? Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatrics 2020, 40, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotnoir-Bichelman, N.M.; Thompson, R.H.; McKerchar, P.M.; Haremza, J.L. Training student teachers to reposition infants frequently. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 2006, 39, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Mahoney, G.; Robinson, C.; Perales, F. Early Motor Intervention: The Need for New Treatment Paradigms. Infants Young Child. 2004, 17, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachry, A.H.; Woods, L. Using the Theoretical Domains Framework and the Behavior Change Wheel to Design a Tummy Time Intervention. J. Occup. Ther. Sch. Early Interv. 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, T.E.; Polanin, J.R.; Evenson, A.L.; Troutman, B.R.; Franklin, C.L. Initial validation of the assessment of parenting tool: A task- and domain-level measure of parenting self-efficacy for parents of infants from birth to 24 months of age. Infant Ment. Health J. 2016, 37, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; W. H. Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Tacke, N.; Bailey, L.; Clearfield, M. Socio-economic Status (SES) Affects Infants’ Selective Exploration. Infant Child Dev. 2015, 24, 571–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piallini, G.; Brunoro, S.; Fenocchio, C.; Marini, C.; Simonelli, A.; Biancotto, M.; Zoia, S. How Do Maternal Subclinical Symptoms Influence Infant Motor Development during the First Year of Life? Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorberg, W.H.; Bekkers, V.J.J.M.; Tummers, L.G. A Systematic Review of Co-Creation and Co-Production: Embarking on the social innovation journey. Public Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 1333–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, M.R.L.; Stougaard, M.S.; Ibsen, B. Transferring Knowledge on Motor Development to Socially Vulnerable Parents of Infants: The Practice of Health Visitors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riethmuller, A.; McKeen, K.; Okely, A.D.; Bell, C.; de Silva Sanigorski, A. Developing an active play resource for a range of Australian early childhood settings: Formative findings and recommendations. Australas. J. Early Child. 2009, 34, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, R.H.; Corwyn, R.F. Socioeconomic Status and Child Development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2002, 53, 371–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Population | Population |

|

|

| Type of intervention | Type of intervention |

|

|

| Caregivers | Caregivers |

|

|

| Geographical and cultural area | Geographical and cultural area |

|

|

| Outcome measure | Study type |

|

|

| Search Strategy | |

|---|---|

| SPORTDiscus | |

| Study type | ((real-life or exploratory or natural* or “Community based” or outreach or intervention* OR prospective) N6 (trial* OR experiment* or investigation* or program* or effort or stud*)) |

| AND | |

| Setting | [“home session”] OR “home environment*” OR “family environment*” OR “child care” OR daycare* OR “child day care” OR nurser* OR care-house* OR “care provider*” OR care-giver* OR “care giver*” OR “health visitor*” OR parent* OR mother* OR father* or home-based or family-based) |

| AND | |

| Population | (baby OR babies OR child* or toddler* or infant* or “Early childhood” OR newborn*) |

| AND | |

| Outcome measure | (“motor activit*” OR “motor performance” OR “Motor skill*” or “motor development*” or “physical activity” OR movement* OR DE “MOTOR ability in children” OR DE “CHILD development”) |

| Scopus | |

| Study type | ((TITLE-ABS-KEY (real-life OR exploratory OR natural* OR “community based” OR outreach OR intervention* OR prospective)) W/6 (TITLE-ABS-KEY (trial* OR experiment* OR investigation* OR program* OR effort OR study*)) |

| AND | |

| Setting | (TITLE-ABS-KEY “home session*” OR “home environment*” OR “family environment*” OR “child care” OR daycare* OR “child day care” OR nurser* OR care-house* OR “care provider*” OR care-giver* OR “care giver*” OR “health visitor*” OR parent* OR mother* OR father* or “home-based” or “family-based”)) |

| AND | |

| Population | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (baby OR babies OR child* OR toddler* OR infant* OR “Early childhood” OR newborn*) |

| AND | |

| Outcome measure | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“motor skill*” OR “motor activit*” OR “motor development*” OR “motor performance” OR “physical activity” OR movement*) |

| APA Psycinfo | |

| Study type | ((real-life or exploratory or natural* or community based or outreach or intervention* or prospective) adj6 (trial* or experiment* or investigation* or program* or effort* or stud*)).mp. |

| AND | |

| Setting | ((home session* or home environment* or family environment*).mp. or home environment/or exp child care/or daycare*.mp. or child day care/or nurser*.mp. or care-house*.mp. or care provider*.mp. or care-giver*.mp. or care giver*.mp. or health visitor*.mp. or parent*.mp. or mother*.mp. or father*.mp. or home-based.mp. or family-based.mp.) |

| AND | |

| Population | (baby or babies or child* or toddler* or infant* or Early childhood or newborn*).mp. |

| AND | |

| Outcome measure | (exp Early Childhood Development/or Motor performance or motor activit* or Motor skill* or motor development* or physical activity or movement*) |

| ERIC | |

| Study type | ((“real-life” OR exploratory OR natural* OR “community based” OR outreach OR intervention* OR prospective) N6 (trial* OR experiment* or investigation*or program* OR effort* OR stud*)) |

| AND | |

| Setting | (DE “Family Environment” OR DE “Child Care” OR “home session*” OR “Home environment*” OR “family environment*” OR daycare* OR “child day care” OR nurser* OR “care-house*” OR “care provider*” OR “care-giver*” OR “care giver*” OR “health visitor*” OR parent* OR mother* OR father* or home-based or family-based) |

| AND | |

| Population | (baby OR babies OR child* OR toddler* or infant* OR “early childhood” OR newborn*) |

| AND | |

| Outcome measure | (“Motor performance” OR “motor activit*” OR “motor skill*” OR “motor development*” OR “physical activity” OR movement* OR DE “Psychomotor Skills” OR DE “Motor Development”) |

| Web of Science | |

| Study type | ((real-life OR exploratory OR natural* OR “community based” OR outreach OR intervention* OR prospective) NEAR/6 (trial* OR experiment* OR investigation* OR program* OR effort OR stud*)) |

| AND | |

| Setting | ((“family environment*” OR “home session*” OR “home environment*” OR “child* care” OR daycare* OR “child* day care” OR nurser* OR care-house* OR “care provider*” OR care-giver* OR “health visitor*” OR “care giver*” OR parent* OR mother* OR father* or “home-based” or “family-based”)) |

| AND | |

| Population | ((baby OR babies OR child* OR toddler* OR infant* OR “Early childhood” OR newborn*)) |

| AND | |

| Outcome measure | (“Motor skill*” OR “motor activit*” OR “motor development*” OR “motor performance” OR “physical activity” OR movement*) |

| - First Author - Country - Year of Publication | Study Type | - Study Population - Age | - Intervention - Control | Duration | Variables | Primary Outcome Measure: Motor Development Outcome Measure | Secondary Outcome Measure: Carers’ Attitudes to and Their Benefits of the Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [29] - Gross - 2017 - USA | Randomised control trial | - Infants Interven-tion (n = 221) Control (n = 235) - 0 months | - An intervention that focuses on increasing the parents’ skills and knowledge in promoting the child’s motor development, e.g., by having the child on its stomach/tummy time, or having the parents place a toy in front of the child while the child is lying on its stomach. - The ordinary everyday life. | 3 months | Motor milestone | In the intervention group, the infants spent significantly more time tolerating the prone position on the floor, compared to the control group. | - |

| [36] - Hewitt - 2020 - Australia | Randomised control trial | - Infants Interven-tion (n = 16) Control (n = 19) - 0–12 weeks | - Mothers received group tummy time classes with their child and family health nurse for 4 weeks at 2 h of lessons. The mothers have to practice with their child at home; moreover, they get messages about practising with their child three times per week. - Mothers received the usual care from their child and family health nurse. | 4 weeks | Motor development was collected at baseline, post-intervention and again when the infants were approximately 6 months old (follow-up). | Post-intervention, there was a moderate effect size for the infant’s ability in prone and sit, favouring the intervention group. | The mothers received the intervention well and found the group practice valuable and relevant. |

| [31] - Lee - USA - 2012 | Non-randomised control trial | - Infants Intervention (n = 11) Control (n = 11) - 1 month | - Caregiver carries out daily activities with a child for 20 min, focusing on improving neck, back, arm and body muscles. Includes rattle and grasp ball. - Caregiver conducts face-to-face communication with the child for 20 min. daily | 1 month | Positioning and head control are measured every two weeks until the baby is 4 months old. | The intervention group has better head control and positioning during the training period and after training stops. | - |

| [30] - Lobo - 2012 - USA | Non-randomised control trial | - Infants Intervention (n = 14) Control (n = 14) - 2 months | - The caregiver carries out a 15-min daily home exercise programme with the child, focusing on back strength and head control (handling and positioning). - The caregiver engages in 15 min of daily face-to-face interaction with the child, with the child lying on its back. | 3 weeks | The child’s motor development was measured immediately after the intervention and with subsequent follow-up tests until the child was 15 months old. | The intervention group scored better in the motor milestone measurements both immediately after the intervention ended and in the follow-up measurements. | The families showed positivity and a greater interest in play and the use of toys with the child |

| [35] - Mendelsohn - 2007 - USA | A single-blind randomised control trial | - Infants to toddlers intervention (n = 52) Control (n = 47) - 0–33 months | - Until the child is 33 months old, the intervention group received video recorded sessions, where a child-development-specialist gives the caregivers feedback on how they react to and what to do with the child. Hereafter, the caregivers get activities to practice at home. They also receive developmentally materials, e.g., toys. The program is based on parenting activities, teaching and playing with their child. - Their normal practice. | 33 months | Motor development and parents’ development were measured. | The intervention group was less likely to have motor development delays than the control group. | The caregivers in the intervention group had improved practising with their child and had a stress reduction, compared to the control group. |

| [32] - Mendres-Smith - 2020 - USA | Observational study with intervention | - Infants (n = 7) - 7 weeks to 4 months | - Two different initiatives: Experiment (1) was guided by the experimenter, the child was laid on its stomach, and the experimenter interacted with the child on a mat (performed at least one day a week for five min duration). Experiment (2) each mother placed the baby breast-to-breast and did different activities with the baby, including a play mat with different features (carried out at least one day a week for five min. duration). | 4 months | The child’s head elevation was measured, as well as knowledge about the child’s contentment (e.g., whining or crying). | Experiment (1) no evidence Experiment (2) increase in the child’s motor milestone in head elevation and a reduction in the child’s whining and crying. | The mothers responded that they found Experiment (2) more effective and favourable. |

| [37] - Palmer - 2019 - USA | Randomised control trial | - Infants and their caregivers Interven-tion (n = 23) Control (n = 19) - 2–5 months of age | - The intervention group get movement lessons about how to guide and help their infants to find new movement possibilities, including positions and use of toys, with a focus on bringing the baby from his or her back to the prone. | One week | Motor-milestone | In the intervention group, the infants spent significantly more time, tolerating the prone position in the week following the lesson. | The caregivers in the intervention group had higher values, indicating more reported knowledge and enjoyment of interacting with the infants. |

| [34] - Schaub - 2019 - Switzer-land | Randomised control trial | - Infants and toddlers Interven-tion: (n = 109) Control: (n = 102) - 0 to 36 months. | - The caregivers get a training program for their young child at home, which a qualified parents educator carries out. The caregivers get a minimum of 10 visits per year and at least one group meeting per year. The parents get activities/training program each visit and knowledge about early motor childhood development and the improvement of parental practices. - | 36 months | Motor-milestones | The intervention group had a more significant proportion of developmental milestones and self-help skills, compared to the control group. | - |

| [33] - Veldman - 2015 - Australia | Non-randomised control trial | - Toddlers Interven-tion: children from two daycare centres (n = 32) Control: children from two other daycare centres (n = 28) - 24 months | - The caregivers carry out 10 min of daily activities with the children, alternating between elements of exploration (e.g., jumping) and balance and extension activities (e.g., kicking). - Their normal practice | 8 weeks | The child’s motor development was measured immediately after the intervention. | The intervention group improved their motor development, compared to the control group. | The caregivers were positive and motivated about the implementation of the intervention. |

| Impact on Motor Development | Impact on the Carers’ Attitudes and Benefits of the Intervention | Duration and Dosage of the Interventions | Factors in the Interventions across the Studies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interventions addressed to 0–36-year-old children. | Overall, the interventions promote the young child’s motor development | Increases the caregiver’s motivation and interest in the young child’s motor development. | Different across the studies | - Knowledge of behaviour to promote the young child’s motor development - Help, guidance, and supervision to the caregivers - To get practice demonstration in their everyday surroundings - Concrete/inspiration to activities that promote the young child’s motor development according to the child’s age - Toys can be an element in the interventions to implement and promote the young child’s motor development - Preferably including the child’s carer(s) who are responsible for carrying out the intervention with the child |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pedersen, M.R.L.; Hansen, A.F. Interventions by Caregivers to Promote Motor Development in Young Children, the Caregivers’ Attitudes and Benefits Hereof: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811543

Pedersen MRL, Hansen AF. Interventions by Caregivers to Promote Motor Development in Young Children, the Caregivers’ Attitudes and Benefits Hereof: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(18):11543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811543

Chicago/Turabian StylePedersen, Marlene Rosager Lund, and Anne Faber Hansen. 2022. "Interventions by Caregivers to Promote Motor Development in Young Children, the Caregivers’ Attitudes and Benefits Hereof: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 18: 11543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811543

APA StylePedersen, M. R. L., & Hansen, A. F. (2022). Interventions by Caregivers to Promote Motor Development in Young Children, the Caregivers’ Attitudes and Benefits Hereof: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811543