Mattering and Depressive Symptoms in Portuguese Postpartum Women: The Indirect Effect of Loneliness

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Loneliness and Depressive Symptoms in the Postpartum Period

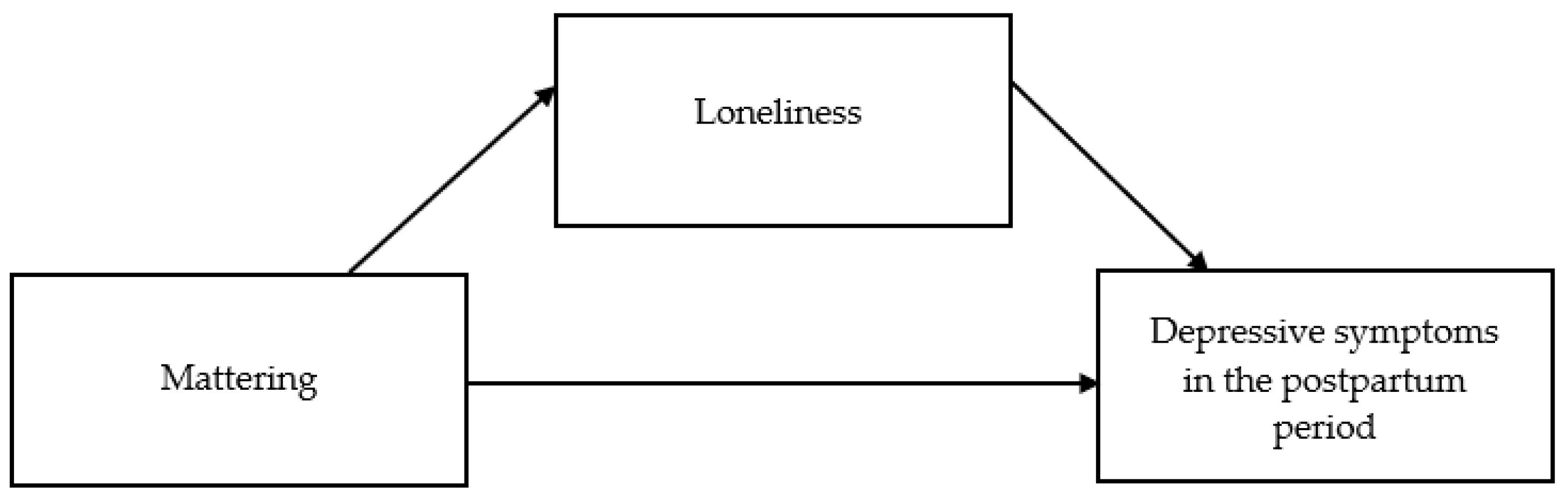

1.2. Mattering and Depressive Symptoms in the Postpartum Period: The Potential Mediating Role of Loneliness

1.3. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedures

2.2. Sample

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Sociodemographic, Clinical, and Infant’s Characteristics

2.3.2. Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)

2.3.3. Loneliness Scale (ULS-6)

2.3.4. General Mattering Scale (GMS; Psychometric Studies of Portuguese Version Ongoing)

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Association between Mattering, Loneliness, and Depressive Symptomatology

3.2. Potential Mediating Role of Loneliness in the Relationship between Mattering and Depressive Symptomatology in Portuguese Women in the Postpartum Period

Preliminary Analyses

3.3. Direct and Indirect Effects of the Relationship between Mattering and Depressive Symptomatology in the Postpartum Period

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Future Research

4.2. Implications for Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wenzel, A.; Kleiman, K. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Perinatal Distress; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara, M.W.; McCabe, J.E. Postpartum depression: Current status and future directions. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 9, 379–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slomian, J.; Honvo, G.; Emonts, P.; Reginster, J.-Y.; Bruyère, O. Consequences of maternal postpartum depression: A systematic review of maternal and infant outcomes. Women’s Health 2019, 15, 1745506519844044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sliwerski, A.; Kossakowska, K.; Jarecka, K.; Switalska, J.; Bielawska-Batorowicz, E. The effect of maternal depression on infant attachment: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letourneau, N.; Duffett-Leger, L.; Dennis, C.L.; Stewart, M.; Tryphonopoulos, P.D. Identifying the support needs of fathers affected by post-partum depression: A pilot study. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2011, 18, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaka, J.; Thompson, S.; Palacios, R. The relation of social isolation, loneliness, and social support to disease outcomes among the elderly. J. Aging Health 2006, 18, 359–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollivier, R.; Aston, M.; Price, S.; Sim, M.; Benoit, B.; Joy, P.; Iduye, D.; Nassaji, N.A. Mental health & parental concerns during COVID-19: The experiences of new mothers amidst social isolation. Midwifery 2021, 94, 102902. [Google Scholar]

- Dol, J.; Richardson, B.; Aston, M.; Mcmillan, D.; Tomblin Murphy, G.; Campbell-Yeo, M. Impact of COVID-19 restrictions on the postpartum experience of women living in Eastern Canada: A mixed method cohort study. medRxiv 2021. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Ostacoli, L.; Cosma, S.; Bevilacqua, F.; Berchialla, P.; Bovetti, M.; Carosso, A.R.; Malandrone, F.; Carletto, S.; Benedetto, C. Psychosocial factors associated with postpartum psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanardo, V.; Manghina, V.; Giliberti, L.; Vettore, M.; Severino, L.; Straface, G. Psychological impact of COVID-19 quarantine measures in northeastern Italy on mothers in the immediate postpartum period. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2020, 150, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, M.H.; Meyer, S.M.; Meah, V.L.; Strynadka, M.C.; Khurana, R. Moms are not OK: COVID-19 and maternal mental health. Front. Glob. Women’s Health 2020, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluska, H.; Shiffman, N.; Mayer, Y.; Margalit, S.; Daher, R.; Elyasyan, L.; Weiner, M.S.; Miremberg, H.; Kovo, M.; Biron-Shental, T.; et al. Postpartum depression in COVID-19 days: Longitudinal study of risk and protective factors. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinola, O.; Liotti, M.; Speranza, A.M.; Tambelli, R. Effects of COVID-19 epidemic lockdown on postpartum depressive symptoms in a sample of Italian mothers. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 589916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Smith, T.B.; Baker, M.; Harris, T.; Stephenson, D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 10, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Hughes, M.E.; Waite, L.J.; Hawkley, L.C.; Thisted, R.A. Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychol. Aging 2006, 21, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanderWeele, T.J.; Hawkley, L.C.; Thisted, R.A.; Cacioppo, J.T. A marginal structural model analysis for loneliness: Implications for intervention trials and clinical practice. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 79, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutel, M.E.; Klein, E.M.; Brähler, E.; Reiner, I.; Jünger, C.; Michal, M.; Wiltink, J.; Wild, P.S.; Münzel, T.; Lackner, K.J.; et al. Loneliness in the general population: Prevalence, determinants and relations to mental health. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Mann, F.; Lloyd-Evans, B.; Ma, R.; Johnson, S. Associations between loneliness and perceived social support and outcomes of mental health problems: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Yap, C.W.; Ong, R.; Heng, B.H. Social isolation, loneliness and their relationships with depressive symptoms: A population-based study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, V.; Moulds, M.L.; Jones, K. Perceived social support and prenatal wellbeing; The mediating effects of loneliness and repetitive negative thinking on anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic. Women Birth 2022, 35, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, J.A.; Williams, R.A.; Seng, J.S. Considering a relational model for depression in women with postpartum depression. Int. J. Childbirth 2014, 4, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, F.; Nigam, A.; Anjum, R.; Agarwalla, R. Postpartum depression in women: A risk factor analysis. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, QC13–QC16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M.; McCullough, B.C. Mattering: Inferred significance and mental health among adolescents. Res. Community Ment. Health 1981, 2, 163–182. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, S.P.; Longmore, M.A.; Manning, W.D.; Giordano, P.C. Strained dating relationships: A sense of mattering and emerging adults’ depressive symptoms. J. Depress. Anxiety 2015, S1, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, J.; Turner, R.J. A longitudinal study of the role and significance of mattering to others for depressive symptoms. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2001, 42, 310–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flett, G.L.; Galfi-Pechenkov, I.; Molnar, D.S.; Hewitt, P.L.; Goldstein, A.L. Perfectionism, mattering, and depression: A mediational analysis. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2012, 52, 828–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Vasileiou, K.; Barnett, J. ‘Lonely within the mother’: An exploratory study of first-time mothers’ experiences of loneliness. J. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 1334–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McComb, S.E.; Goldberg, J.O.; Flett, G.L.; Rose, A.L. The double jeopardy of feeling lonely and unimportant: State and trait loneliness and feelings and fears of not mattering. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 563420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flett, G.L.; Goldstein, A.L.; Pechenkov, I.G.; Nepon, T.; Wekerle, C. Antecedents, correlates, and consequences of feeling like you don’t matter: Associations with maltreatment, loneliness, social anxiety, and the five-factor model. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2016, 92, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.L.; Holden, J.M.; Sagovsky, R. Detection of postnatal depression. Br. J. Psychiatry 1987, 150, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, B. Depressão Pós-Parto, Interacção Mãe-Bebé e Desenvolvimento Infantil. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Minho, Braga, Portugal, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Neto, F. Psychometric analysis of the short-form UCLA loneliness scale (ULS-6) in older adults. Eur. J. Ageing 2014, 11, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, F.M. Mattering: Its measurement and theoretical significance for social psychology. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Eastern Sociological Association, Cincinnati, OH, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Flett, G. The Psychology of Mattering: Understanding the Human Need to Be Significant; Elsevier Science: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Gou, Z.; Zuo, J. Social support mediates loneliness and depression in elderly people. J. Health Psychol. 2014, 21, 750–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardrop, A.; Popadiuk, N. Women’s experiences with postpartum anxiety: Expectations, relationships, and sociocultural influences. Qual. Rep. 2013, 18, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, N.B.; Harrison, B.; Fambro, S.; Bodnar, S.; Heckman, T.G.; Sikkema, K.J. The structure of coping among older adults living with HIV/AIDS and depressive symptoms. J. Health Psychol. 2012, 18, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkley, L.C.; Cacioppo, J.T. Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann. Behav. Med. 2010, 40, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Robertson, E.; Grace, S.; Wallington, T.; Stewart, D.E. Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: A synthesis of recent literature. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2004, 26, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.L.; Steger, M.F. Giving birth to meaning: Understanding parenthood through the psychology of meaning in life. In Pathways and Barriers to the Transition to Parenthood—Existential Concerns Regarding Fertility, Pregnancy, and Early Parenthood; Taubman-Ben-Ari, O., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, M. The mediation effect of mattering and self-esteem in the relationship between socially prescribed perfectionism and depression: Based on the social disconnection model. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2015, 88, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, M.W. Postpartum depression: What we know. J. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 65, 1258–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchens, B.F.; Kearney, J. Risk factors for postpartum depression: An umbrella review. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2020, 65, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mattering (GMS) | Loneliness (ULS-6) | Depressive Symptoms (EPDS) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GMS | - | ||

| ULS-6 | −0.69 ** | - | |

| EPDS | −0.48 ** | 0.56 ** | - |

| Age | Education Level | Residence | Baby’s Age | Number of Children | Gestation Week at Birth | EPDS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | - | ||||||

| Educational level | 0.24 ** | - | |||||

| Residence | −0.08 | −0.13 ** | - | ||||

| Baby’s age | 0.08 | 0.01 | −0.08 | - | |||

| Number of children | 0.35 ** | −0.03 | −0.02 | −0.02 | - | ||

| Gestation week at birth | −0.07 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | - | |

| EPDS | −0.10 * | −0.17 ** | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.09 * | 0.00 | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caetano, B.; Branquinho, M.; Canavarro, M.C.; Fonseca, A. Mattering and Depressive Symptoms in Portuguese Postpartum Women: The Indirect Effect of Loneliness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11671. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811671

Caetano B, Branquinho M, Canavarro MC, Fonseca A. Mattering and Depressive Symptoms in Portuguese Postpartum Women: The Indirect Effect of Loneliness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(18):11671. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811671

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaetano, Bárbara, Mariana Branquinho, Maria Cristina Canavarro, and Ana Fonseca. 2022. "Mattering and Depressive Symptoms in Portuguese Postpartum Women: The Indirect Effect of Loneliness" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 18: 11671. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811671