Psychological, Psychosocial and Obstetric Differences between Spanish and Immigrant Mothers: Retrospective Observational Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Perinatal Depression

1.2. Sociodemographic Factor

1.3. Psychosocial Factors and Immigration

1.4. Obstetric Problems

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Settings

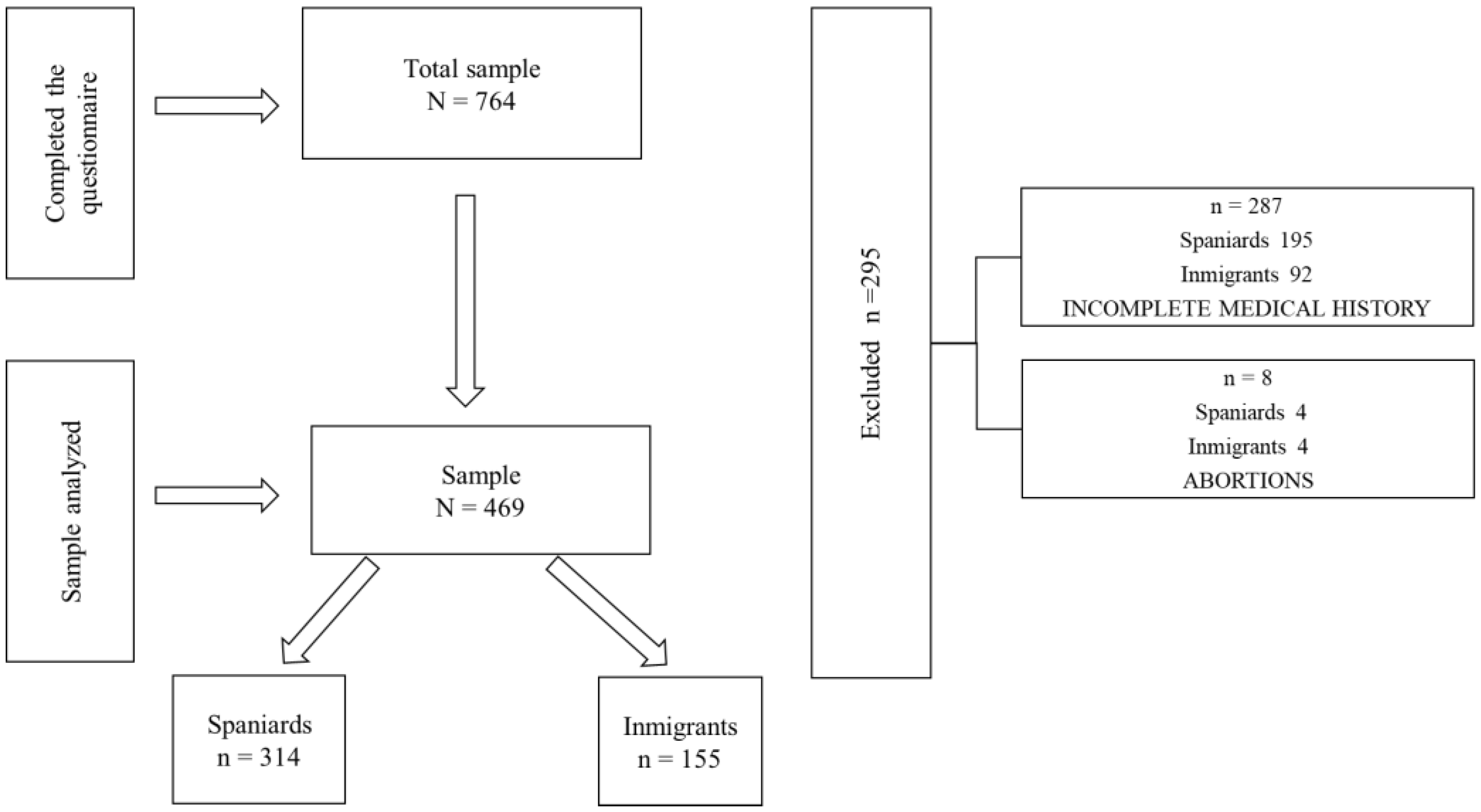

2.3. Participants

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Instruments

2.5.1. PDPI-R

2.5.2. PHQ-9

2.5.3. Obstetric Variables

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Profile of the Participants

3.2. Depression Rates in Women Giving Birth: Severity of Depressive Symptomatology (Total of Spaniards and Immigrants)

3.3. Prevalence of Sociodemographic Factors and Symptoms of Depression by Origin

3.4. Types of Support at the Partner, Family and Friendship Levels

3.5. Pregnancy Complications

3.6. Caesarean Section

3.7. Week of Gestation to Delivery

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fonseca, A.; Ganho-Ávila, A.; Lambregtse-van den Berg, M.; Lupatelli, A.; Rodriguez-Muñoz, M.F.; Ferreira, P.; Radoš, S.N.; Bina, R. Emerging issues and questions on peripartum depression prevention, diagnosis and treatment: A consensus report from the COST Action RISEUP-PPD. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 274, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, J.L.; Carandang, R.R.; Kharel, M.; Shibanuma, A.; Yarotskaya, E.; Basargina, M.; Jimba, M. Effects of mHealth on the psychosocial health of pregnant women and mothers: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e056807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagadec, N.; Steinecker, M.; Kapassi, A.; Magnier, A.M.; Chastang, J.; Roberto, S.; Gaouaou, N.; Ibanez, G. Factors influencing the quality of life of pregnant women: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branquinho, M.; Rodriguez-Muñoz, M.F.; Maia, B.R.; Marques, M.; Matos, M.; Osma, J.; Moreno-Peral, P.; Conejo-Cerón, S.; Fonseca, A.; Vousoura, E. Effectiveness of psychological interventions in the treatment of perinatal depression: A systematic review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 291, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 343: Psychosocial risk factors: Perinatal screening and intervention. Obs. Gynecol. 2006, 108, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Antenatal Care; NICE Guideline, No. 201; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): London, UK, 2021. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK573778/ (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Marcos-Nájera, R.; Rodríguez-Muñoz, M.D.L.F.; Soto Balbuena, C.; Olivares Crespo, M.E.; Izquierdo Mendez, N.; Le, H.N.; Escudero Gomis, A. The prevalence and risk factors for antenatal depression among pregnant immigrant and native women in Spain. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2020, 31, 564–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, R.F. Prevent depression in pregnancy to boost all mental health. Nature 2019, 574, 631–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grotti, V.; Malakasis, C.; Quagliariello, C.; Sahraoui, N. Shifting vulnerabilities: Gender and reproductive care on the migrant trail to Europe. Comp. Migr. Stud. 2018, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuesta, C.R. La salud en la mujer inmigrante; factores psicosociales y patologías más frecuentes. [Health in immigrant women; psychosocial factors and more frequent pathologies]. Psicosomàtica Psiquiatr. 2019, 10, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fair, F.; Raben, L.; Watson, H.; Vivilaki, V.; van den Muijsenbergh, M.; Soltani, H.; ORAMMA Team. Migrant women’s experiences of pregnancy, childbirth and maternity care in European countries: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Martínez, J.G.; de la Cruz, M.A.; Sánchez, Z.F.; del Río Romero, I.; Bonal, Z.N.; Ballarín, P.P.; Garrido, M.P. ¿Es la nacionalidad de la paciente un factor influyente en el proceso de embarazo, parto y puerperio? [Does the nationality of the patient have an influence on the process of pregnancy, childbirth and post-partum?]. Clín. E Investig. En Ginecol. Y Obstet. 2021, 48, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, F.M.; Hatch, S.L.; Comacchio, C.; Howard, L.M. Prevalence and risk of mental disorders in the perinatal period among migrant women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2017, 20, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, S.D.; Mann, L.; Simán, F.M.; Song, E.; Alonzo, J.; Downs, M.; Lawlo, E.; Martínez, O.; Sun, C.J.; O’Brien, M.C.; et al. The impact of local immigration enforcement policies on the health of immigrant Hispanics/Latinos in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayment-Jones, H.; Harris, J.; Harden, A.; Silverio, S.A.; Turienzo, C.F.; Sandall, J. Project20: Interpreter services for pregnant women with social risk factors in England: What works, for whom, in what circumstances, and how? Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadi, A.F.; Miller, E.R.; Bisetegn, T.A.; Mwanri, L. Global burden of antenatal depression and its association with adverse birth outcomes: An umbrella review. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accortt, E.E.; Cheadle, A.C.; Schetter, C.D. Prenatal depression and adverse birth outcomes: An updated systematic review. Matern. Child Health J. 2015, 19, 1306–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sociedad Española de Ginecología y Obstetricia [SEGO]. Control prenatal del embarazo normal. [Prenatal control of normal pregnancy]. Prog. Obstet. Ginecol. (Ed. Impr.) 2018, 61, 510–527. Available online: https://sego.es/documentos/progresos/v61-2018/n5/GAP_Control%20prenatal%20del%20embarazo%20normal_6105.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Ibarra-Yruegas, B.; Lara, M.A.; Navarrete, L.; Nieto, L.; Kawas Valle, O. Psychometric properties of the Postpartum Depression Predictors Inventory–Revised for pregnant women in Mexico. J. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 1415–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Muñoz, M.F.; Vallejo, L.; Olivares, M.E.; Izquierdo, N.; Soto, C.; Le, H.N. Propiedades Psicométricas Del Inventario de Predictores de Depresión Posparto-Revisado-Versión-prenatal en una Muestra Española de Mujeres Embarazadas. [Psychometric Properties of the Inventory-Revised- Prenatal Version in a Sample of Spanish Pregnant Women]. Revista Española Salud Pública 2017, 91, 20–47. Available online: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1135-57272017000100422&lng=es (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Oppo, A.; Mauri, M.; Ramacciotti, D.; Camilleri, V.; Banti, S.; Borri, C.; Rambelli, C.; Montagnani, M.S.; Cortopassi, S.; Bettini, A.; et al. Risk factors for postpartum depression: The role of the Postpartum Depression Predictors Inventory-Revised (PDPI-R). Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2009, 12, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R. The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr. Ann. 2002, 32, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manea, L.; Gilbody, S.; McMillan, D. A diagnostic meta-analysis of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) algorithm scoring method as a screen for depression. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2015, 37, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College of Obstetrician and Gynecologist. Screening for perinatal depression. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 132, 208–212. Available online: https://www.acog.org/-/media/project/acog/acogorg/clinical/files/committee-opinion/articles/2018/11/screening-for-perinatal-depression.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, M. Symptom Severity and Guideline-Based Treatment Recommendations for Depressed Patients: Implications of DSM-5’s Potential Recommendation of the PHQ-9 as the Measure of Choice for Depression Severity. Psychother. Psychosom. 2012, 81, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbody, S.; Richards, D.; Brealey, S.; Hewitt, C. Screening for depression in medical settings with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): A diagnostic meta-analysis. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2007, 22, 1596–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcos-Nájera, R.; Le, H.N.; Rodríguez-Muñoz, M.F.; Olivares, M.E.; Izquierdo, N. The structure of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 in pregnant women in Spain. Midwifery 2018, 62, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INE. Estadísticas del Movimiento Natural de la Población (Nacimientos, Defunciones y Matrimonios). Año 2019 [Statistics of the Natural Movement of the Population (Births, Deaths and Marriages). Year 2019]. Available online: https://www.ine.es/prensa/mnp_2019_p.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Robertson, E.; Grace, S.; Wallington, T.; Stewart, D. Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: A synthesis of recent literature. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2004, 26, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Castillo Acuña, F.E. La migración de cuerpo y mano de obra femenina a Andalucía. El trabajo doméstico: Una visión antropológica [The migration of female body and workforce to Andalusia. Domestic work: An anthropological vision]. In Diversidad Cultural y Migraciones; Comares: University of Granada: Granada, Spain, 2013; pp. 65–82. Available online: https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/52163103/Diversidadculturalymigraciones_GarciaKressova2013-with-cover-page-v2.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Gaviria, S.L.; Duque, M.; Vergel, J.; Restrepo, D. Síntomas depresivos perinatales: Prevalencia y factores psicosociales asociados [Perinatal depressive symptoms: Prevalence and associated psychosocial factors]. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. 2019, 48, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazier, R.; Elgar, F.; Goel, V.; Holzapfel, S. Stress, social support, and emotional distress in a community sample of pregnant women. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 25, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoozak, L.; Gotman, N.; Smith, M.V.; Belanger, K.; Yonkers, K. Evaluation of a social support measure that may indicate risk of depression during pregnancy. J. Affect. Disord. 2009, 114, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, M.O.; Jiménez, M.R.; Largo, Á.M. Depresión materna perinatal y vínculo madre-bebé: Consideraciones clínicas [Maternal perinatal depression and mother-infant bond: Clinical considerations]. Summa Psicológica UST 2015, 12, 77–87. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5147360 (accessed on 8 July 2022). [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 222: Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Obs. Gynecol 2020, 135, e237–e260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rueda, B.; Alemán, J.F. Anxiety and Depression in Hypertensive Women: Influence on Symptoms and Alexithymia. Arch. Clin. Hypertens. 2015, 1, 10–16. Available online: https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/41629428/ACH-1-103-with-cover-page-v2.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2022). [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Statement on Caesarean Section Rates. 2015. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/161442/WHO_RHR_15.02_eng.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Garcia-Tizon, S.L.; Arevalo-Serrano, J.; Duran Vila, A.; Pintado Recarte, M.P.; Cueto Hernandez, I.; Solis Pierna, A.; Lizarraga Bonelli, S.; Leon-Luis, D. Human Development Index (HDI) of the maternal country of origin as a predictor of perinatal outcomes-a longitudinal study conducted in Spain. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Robson Classification: Implementation Manual. 2017. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259512 (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- Osterman, M.J.; Hamilton, B.E.; Martin, J.A.; Driscoll, A.K.; Valenzuela, C.P. Births: Final Data for 2020. 2022. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/112078 (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Fonseca Pedrero, E.; Pérez-Álvarez, M.; Al-Halabí, S.; Inchausti, F.; Muñiz, J.; López-Navarro, E.; Pérez de Albéniz, A.; Lucas Molina, B.; Debbané, M.; Bobes-Bascarán, M.T.; et al. Evidence-Based Psychological Treatments for Adults: A Selective Review. Psicothema 2021, 33, 188–197. Available online: https://reunido.uniovi.es/index.php/PST/article/view/17086 (accessed on 29 July 2022). [PubMed]

| Spaniards n (314) 67% | Inmigrants n (155) 33% | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | t | ||

| Age | 34.72 | 4.77 | 31.74 | 5.63 | 5.997 ** | |

| Week of pregnancy | 39.32 | 1.8 | 38.65 | 2.72 | 3.159 ** | |

| n | % | n | % | χ2 | Cramer’s V | |

| Employment | 11.372 * | 0.156 | ||||

| Active | 250 | 80.1 | 103 | 67.3 | ||

| Unemployed | 15 | 4.8 | 18 | 11.8 | ||

| Housewives | 46 | 14.8 | 31 | 20.3 | ||

| Disability | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.7 | ||

| Level of study | 70.293 ** | 0.388 | ||||

| No studies | 4 | 1.3 | 6 | 3.9 | ||

| Basics | 28 | 9 | 20 | 12.9 | ||

| Medium-high | 74 | 23.7 | 89 | 57.4 | ||

| University | 206 | 66 | 40 | 25.8 | ||

| Marital status | 17.722 ** | 0.195 | ||||

| Married | 163 | 52.1 | 67 | 43.8 | ||

| Single | 34 | 10.9 | 38 | 24.8 | ||

| Live with a partner | 114 | 36.4 | 45 | 29.4 | ||

| Widow | 1 | 0.3 | 2 | 1.3 | ||

| Separated/divorced | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.7 | ||

| Smoking | 3.067 | |||||

| Yes | 34 | 18 | 7 | 9.3 | ||

| No | 155 | 82 | 68 | 90.7 | ||

| Drinking alcohol | 1.046 | |||||

| Yes | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5.8 | ||

| No | 162 | 97 | 65 | 94.2 | ||

| Primiparous mothers | 7.200 ** | 0.125 | ||||

| Yes | 151 | 48.9 | 55 | 35.7 | ||

| No | 158 | 51.1 | 99 | 64.3 | ||

| Previous depression | 1.832 | |||||

| Yes | 11 | 3.6 | 2 | 1.3 | ||

| No | 297 | 96.4 | 148 | 98.7 | ||

| Spaniards n | Immigrants n | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | t | ||

| Depression Symptoms | 0.18 | 0.425 | 0.35 | 0.719 | −3.042 ** | |

| PHQ-9 Severity | n | % | n | % | χ2 | Cramer’s V |

| No symptoms of depression (<10) | 264 | 84.1% | 119 | 76.8% | 3.695 | |

| Moderate depression symptoms (10–14) | 45 | 14.3% | 23 | 14.8% | 0.022 | |

| Moderately severe symptoms (15–19) | 5 | 1.6% | 9 | 5.8% | 6.364 * | 0.116 * |

| Severe symptoms (≥20) Major depression epression | 0 | 5 | 3.2% | 10.238 ** | 0.148 * | |

| PHQ-9 | Spaniards | Immigrants | χ2 | Cramer’s V | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||||

| Partner | With partner | 41 | 13.8 | 19 | 13.7 | 17.450 ** | 0.200 |

| No partner | 7 | 2.3 | 13 | 9.3 | |||

| Studies | No studies/ Basics | 39 | 13.1 | 25 | 17.9 | 16.306 ** | 0.193 |

| Medium/ Higher | 9 | 3.1 | 7 | 5 | |||

| Employment situation | Employed | 33 | 11 | 15 | 9.7 | 18.886 ** | 0.208 |

| Unemployed | 11 | 5 | 17 | 12.2 | |||

| Previous depression | 4 | 1.3 | 1 | 0.7 | 28.054 ** | 0.256 | |

| Primiparous mothers | 25 | 8.5 | 7 | 5 | 1.262 | ||

| Lack of partner support | 3 | 1 | 8 | 5.9 | 13.909 ** | 0.181 | |

| Lack of family support | 5 | 1.7 | 10 | 7.3 | 49.150 ** | 0.338 | |

| Lack of friendly support | 5 | 1.7 | 14 | 10.4 | 17.631 ** | 0.204 | |

| Partner dissatisfaction | 2 | 0.8 | 7 | 5.5 | 8.936 * | 0.147 | |

| Problems with the partner | 4 | 1.5 | 3 | 2.4 | 4.861 | ||

| They don’t feel good in the relationship | 45 | 15.7 | 23 | 17.9 | 6.871 | ||

| Social Support | Spaniards | Immigrants | χ2 | Cramer’s V | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Lack of partner support | ||||||

| Emotional | 20 | 6.6 | 20 | 13.4 | 5.709 * | 0.113 |

| Trust | 12 | 4 | 14 | 9.5 | 5.583 * | 0.112 |

| Count on the partner | 12 | 4 | 14 | 9.5 | 5.447 * | 0.110 |

| Practical support | 23 | 7.6 | 22 | 15.1 | 6.050 * | 0.116 |

| Lack of family support | ||||||

| Emotional | 15 | 4.9 | 16 | 10.8 | 5.428 * | 0.109 |

| Trust | 11 | 3.6 | 12 | 8.1 | 4.081 * | 0.095 |

| Count on the family | 10 | 3.3 | 15 | 10.1 | 8.809 ** | 0.139 |

| Practical support | 32 | 10.6 | 32 | 21.8 | 10.191 ** | 0.150 |

| Lack of friendly support | ||||||

| Emotional | 11 | 3.6 | 14 | 9.5 | 6.505 * | 0.120 |

| Trust | 9 | 3 | 27 | 18.6 | 32.079 ** | 0.268 |

| Count on friends | 15 | 5 | 30 | 20.5 | 26.170 ** | 0.242 |

| Practical support | 54 | 18.1 | 49 | 34.5 | 14.548 ** | 0.182 |

| Relationship with partner | ||||||

| Dissatisfaction with the relationship | 12 | 4.1 | 16 | 11.3 | 8.413 ** | 0.139 |

| Partner problems | 20 | 6.7 | 10 | 7.1 | 0.019 | |

| Not well in partner | 17 | 5.7 | 16 | 11.3 | 4.384 * | 0.100 |

| Descriptive Complications | Spaniards | Immigrants | χ2 | Cramer’s V | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| High obstetric risk | 13 | 3.5 | 2 | 0.5 | 2.561 | |

| Intrauterine Growth, Restriction (IUGR) TYPE I | 6 | 1.7 | 1 | 0.3 | 1.099 | |

| IUGR TYPE II | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.493 | ||

| HTA high | 1 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.6 | 1.513 | |

| Mild preeclampsia | 0 | 2 | 0.6 | 4.006 * | 0.106 | |

| Severe preeclampsia | 2 | 0.6 | 2 | 0.6 | 0.512 | |

| Suspicion of threat of early birth labor | 3 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.116 | |

| Placenta praevia | 0 | 3 | 0.8 | 5.975 * | 0.129 | |

| Cervical shortening with pessary | 4 | 1.1 | 2 | 0.6 | 0.000 | |

| Cervical shortening without pessary | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.493 | ||

| High fetal cardiological risk | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.493 | ||

| Vaginal or urinary infections | 2 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.000 | |

| Poor obstetric control | 1 | 0.3 | 3 | 0.8 | 3.123 | |

| Fetus small for gestational age | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.258 | |

| Suspected macrosomic fetus | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.258 | |

| Thrombocytopenia | 13 | 5.2 | 1 | 0.3 | 4.150 * | 0.106 |

| High risk of Down’s Syndrome | 2 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 0.985 | |

| Syphilis | 0 | 1 | 0.8 | 2.014 | ||

| Repeated miscarriages and hypertransaminases | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.493 | ||

| Severe preeclampsia and Intrauterine Growth Restriction (IUGR) | 0 | 2 | 0.6 | 4.006 * | 0.106 | |

| Reason for C-Section | Spaniards | Immigrants | χ2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Cephalic pelvic disproportion | 12 | 3.2 | 2 | 0.5 | 2.187 |

| Podalic presentation | 3 | 0.8 | 0 | 1.481 | |

| Polyhydramnios, transverse lie, uterine hypotonia and high risk of Down’s Syndrome | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.495 | |

| No progression of labor | 13 | 3.5 | 6 | 1.6 | 0.020 |

| Suspected fetal compromise | 22 | 7.7 | 23 | 5.8 | 3.259 |

| Failed labor induction | 7 | 1.9 | 3 | 0.8 | 0.044 |

| Requested by the patient | 2 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.000 |

| Placenta praevia | 4 | 1.1 | 2 | 0.6 | 0.000 |

| Placental abruption | 5 | 1.4 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.726 |

| Iterative | 1 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.6 | 1.502 |

| Iterative with tubal ligation | 1 | 0.3 | 3 | 0.8 | 3.105 |

| Breech presentation | 2 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.989 | |

| Non-reassuring fetal heart rate, sustained fetal bradycardia, loss of fetal well-being | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.255 |

| Difficult extraction of the fetus, very ascended vesicouterine plica, requires dissection 1 with a swab. | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.495 | |

| Urgent caesarean section with LMWH prophylaxis (anticoagulant in pregnancy) | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.495 | |

| IUGR type II | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.495 | |

| Fetal maternal interest | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.255 |

| Scheduled caesarean section | 2 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.989 | |

| Twin gestation (diamniotic dichorionic, scheduled caesarean section for breech-cephalic presentation) | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.495 | |

| Preterm, premature rupture of membranes, tocolysis with Atosiban | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.495 | |

| Placenta praevia, transverse lie | 0 | 1 | 0.3 | 2.006 | |

| Fetal pathology | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.495 | |

| Due to risk of the first baby and feticide of the second fetus, pelvic-cephalic disproportion, premature rupture of the membranes at term | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.495 | |

| Pelvic-cephalic disproportion, premature rupture of membranes at term | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.495 | |

| Severe preeclampsia with macrosomia | 0 | 1 | 0.3 | 2.006 | |

| Metrorrhagia, maternal anemia, suspected placental abruption and fetal malposition | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.495 | |

| Week of Pregnancy at Birth | Spaniards | Immigrants | χ2 | Cramer’s V | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Extremely premature (20–28 weeks) | 0 | 3 | 2 | 5.526 * | 0.124 | |

| Very premature (28–32 weeks) | 0 | 2 | 1.3 | 3.703 | ||

| Moderately premature (32–37 weeks) | 29 | 9.5 | 16 | 10.5 | 0.009 | |

| At term (37–41 weeks) | 232 | 75.8 | 124 | 81.6 | 2.122 | |

| Post-term (41–42 weeks) | 45 | 14.7 | 7 | 4.6 | 9.505 ** | 0.153 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martínez Herreros, M.C.; Rodríguez Muñoz, M.F.; Izquierdo Méndez, N.; Olivares Crespo, M.E. Psychological, Psychosocial and Obstetric Differences between Spanish and Immigrant Mothers: Retrospective Observational Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11782. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811782

Martínez Herreros MC, Rodríguez Muñoz MF, Izquierdo Méndez N, Olivares Crespo ME. Psychological, Psychosocial and Obstetric Differences between Spanish and Immigrant Mothers: Retrospective Observational Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(18):11782. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811782

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartínez Herreros, María Carmen, María Fe Rodríguez Muñoz, Nuria Izquierdo Méndez, and María Eugenia Olivares Crespo. 2022. "Psychological, Psychosocial and Obstetric Differences between Spanish and Immigrant Mothers: Retrospective Observational Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 18: 11782. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811782

APA StyleMartínez Herreros, M. C., Rodríguez Muñoz, M. F., Izquierdo Méndez, N., & Olivares Crespo, M. E. (2022). Psychological, Psychosocial and Obstetric Differences between Spanish and Immigrant Mothers: Retrospective Observational Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11782. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811782