1. Introduction

The fourth wave of the COVID-19 pandemic had a dramatic impact in Romania, with unprecedentedly high infection rates, registering the second highest per capita COVID-19 death rate in the world in October 2021 [

1]. With one of the most underdeveloped healthcare systems in the European Union regarding infrastructure, sufficient staffing, and financing [

2], the Romanian healthcare system quickly became overwhelmed [

3,

4]. Mirroring the global trend, nurses’ exposure to PMIEs spiked during this pandemic in Romania, with severe consequences on their wellbeing and psychological health, including—but not restricted to—moral injury [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

Potentially Morally Injurious Events (PMIEs) are events which imply “perpetrating, failing to prevent, bearing witness to, or learning about acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations” [

10] (p. 697). Self-PMIEs are moral transgressions enacted under perceived external coercion, while other-PMIEs are moral transgressions to which the person assists without speaking/acting out, despite feeling as if they should. Exposure to PMIEs was associated with poorer COVID-19 psycho-social functional improvement over time in healthcare providers, especially for self-perpetrated PMIEs [

11]. One potential explanation for this trend is the negative impact of the repeated recall of autobiographical episodic memories of these events. Thus, studies found that nurses’ episodic memories of PMIEs can have a unique negative association with their burnout, work motivation, work satisfaction, and adaptive performance several months after the event, mediated by autonomy thwarting [

12]. Memories of self-PMIEs had stronger associations with burnout and turnover intentions compared to memories of other-PMIEs (i.e., enacted vs. witnessed PMIEs), mediated by the thwarting of all three basic psychological needs [

13]. However, it remains unclear whether both memories of self-PMIEs and other-PMIEs would be associated with more burnout and turnover intentions when compared to a control group. This would be important to ascertain because it would contribute to our currently limited understanding of the distinctive harmful outcomes of exposure to self- and other-PMIEs [

5,

14,

15,

16]. Thus, our first aim was to experimentally investigate these differential associations with nurses’ occupational wellbeing and turnover intentions, mediated by the thwarting of all three basic psychological needs [

17].

To date, protective factors against the negative effects of autobiographical episodic memories on psychological health and wellbeing have not been investigated, to the best of our knowledge. Previous findings suggest that nurses’ memories of PMIEs from the COVID-19 pandemic may not have yet been integrated in their autobiographical knowledge, an integration which might dramatically affect their work identities, behavior, and psychological health, with potential consequences on the healthcare organizational system [

13]. Thus, departing from the mediating factors proposed, we set out to explore two potential moderators for the impact of memories of self- and other-PMIEs on burnout, turnover intentions, and work engagement. Perceived supervisor support and self-disclosure were assessed as moderators for autonomy and, respectively, relatedness thwarting.

1.1. Episodic Memories of PMIEs

Although correlated, self-PMIEs and other-PMIEs are distinct concepts, affecting psychological health differently [

5,

15,

16]. However, this differential impact is still controversial. Thus, one study found that both were associated with increased depressive symptomatology in healthcare workers, but only self-PMIEs were associated with increased anxiety, PTSD, burnout, and disengagement [

5]. Another study indicated that both types of PMIE could be associated with higher burnout, higher depressive symptoms, and worse quality of life in healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic [

14].

According to Self-Determination Theory (SDT), the three basic psychological needs are autonomy (i.e., the need to feel volitional and authentic in actions), competence (i.e., the need to feel effective and efficacious), and relatedness (i.e., the need to feel mutual connectedness and caring) [

17]. In a previous study we conducted, our findings suggested that nurses’ work-related, autobiographical episodic memories of PMIEs during the COVID-19 pandemic had unique associations with increased burnout and, respectively, decreased work motivation, work satisfaction, and adaptive performance compared to their memories of severe moral transgressions (SMTs) [

12]. In this study, we used SMTs as a control group, because they are similar to PMIEs in perceived moral severity, but different in terms of perceived external coercion. Thus, one of the defining characteristics of PMIEs is that they are moral transgressions perpetrated/witnessed against the person’s will (e.g., a nurse who prioritizes a younger patient over an older patient, based on directives according to which age is an indicator of odds of survival, and against their moral and professional ethical code, which would lead them to prioritize according to how critical the patient’s condition was) [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. In contrast, SMTs are more similar to medical errors, in that the outcome of the transgression is very harmful (i.e., high in moral severity) [

18,

19,

20], but the transgression is enacted in the absence of perceived external pressures (i.e., a nurse who chooses to come to work even if they are aware of being infected with the new coronavirus and spreads the disease to their patients) [

20]. The differential associations of PMIEs and SMTs with the outcomes specified above were mediated by the extent to which nurses’ autonomy was thwarted in the two memories. Memories of PMIEs were associated with higher autonomy thwarting than memories of SMTs, which, in turn, was associated with more negative psychological health outcomes. However, we did not distinguish between self- and other-PMIEs in this study, treating PMIEs as a singular construct. We also did not explore the mediational role of the other two basic psychological needs (i.e., competence and autonomy) in the differences between PMIEs and SMTs in burnout. We address both these aspects in the current study.

In a different study, we compared nurses’ memories of self-PMIEs to their memories of other-PMIEs during the COVID-19 pandemic and found that the former had a stronger association with increased burnout and turnover intentions, mediated by all three basic psychological needs [

13]. Thus, memories of self-PMIEs were more autonomy- and competence-thwarting than memories of other-PMIEs, a difference which we attributed to the omission bias [

19]. When people enact a moral violation, they judge it as more harmful and blameworthy than when they allow it to happen without interfering. Hence, when forced to perpetrate an immoral act, it is likely that nurses perceived they had less autonomy than when forced to passively witness one, to justify their immoral behavior to themselves [

20]. With moral values being central to their professional identities [

21], their competence was also more threatened during self-PMIEs, which constituted a more direct threat to their identity compared to other-PMIEs [

20,

22]. In contrast, relatedness was more thwarted in memories of other-PMIEs compared to self-PMIEs, because they represent acts of organizational betrayal, put in motion by their peers or superiors [

5,

15,

16]. Other-PMIEs were shown to be perceived as signs of disrespect towards nurses and exclusion from medical decision making [

23,

24,

25], while self-PMIEs represent more distal acts of betrayal [

15,

16]. However, in this research, we did not use a control group in our design, nor did we explore differences in work engagement. Investigating work engagement alongside burnout is important because, although they do not form a single construct, work engagement contributes to our understanding of occupational wellbeing by adding the dimension of studying the characteristics of normal and satisfactory activity to the more pathology-oriented dimensions of burnout [

26,

27].

To our knowledge, so far, there are no studies which compare nurses’ memories of self-PMIEs and other-PMIEs from the COVID-19 pandemic to SMTs (i.e., a control group) in terms of associations with occupational wellbeing, comprising work engagement, and burnout, and, respectively, turnover intentions. Given the mixed findings on the effects of exposure to self- and other-PMIEs [

5,

13,

14,

15,

16], it could be that the impact of memories of other-PMIEs is either not different or smaller than the impact of SMTs, since the latter can be need-thwarting as well, especially in terms of competence. On the other hand, this impact could be greater, because they could be more autonomy-thwarting than memories of SMTs [

12,

13], since they constitute passive moral transgressions perpetrated under environmental constraint [

15,

16]. These perceived environmental constraints represent morally laden limitations imposed on nurses by peers/supervisors/legislators during the pandemic, which could lead to more intense feelings of being disconnected from others and uncared for by them [

15,

16], which could, in turn, translate into more relatedness thwarting for memories of other-PMIEs compared to SMTs. The differential need thwarting of these types of events has direct implications for the types of interventions necessary for addressing the deficits in occupational wellbeing and turnover intentions associated with the two types of memories [

10,

16], as well as for prevention and reparatory efforts, which may focus on improving certain protective factors, such as perceived supervisor support and self-disclosure.

1.2. Perceived Supervisor Support

Perceived supervisor support is an organizational factor shown to influence nurses’ work satisfaction, job performance, and turnover intentions [

28,

29,

30,

31]. When nurses believe their supervisors value their contributions and care about their wellbeing [

28], they experience more autonomy and job satisfaction, have lower turnover intentions, and provide better patient care [

30,

32]. Then, higher perceived supervisor support could decrease the impact of memory-related autonomy thwarting on wellbeing and turnover intentions. Knowing that their supervisor is fair and generally supportive of their autonomy could help them restructure their PMIE memories upon repeated recall as caused by exceptional circumstances uncharacteristic for their workplace [

33].

1.3. Self-Disclosure

Self-disclosure is the process through which people allow themselves to be known by others [

34], helping them cope with traumatic events [

35,

36], and operating as a protective factor against suicidal behavior [

37]. By boosting social support and belongingness, it also protected war veterans against suicidal ideation after exposure to PMIE [

38]. As such, nurses with higher levels of self-disclosure share their PMIE-related experiences, increasing their sense of belonging and social support, which could mitigate the negative influence of relatedness thwarting on their wellbeing and turnover intentions.

1.4. Occupational Wellbeing and Turnover Intentions during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Nurses’ wellbeing and turnover intentions were dramatically impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, with consequences on patient care and their health [

39,

40]. Exposure to PMIEs and subsequent moral injury have been associated with decreased wellbeing and increased turnover intentions in healthcare providers and other populations, especially since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic [

16,

41,

42,

43]. With severe negative consequences at the individual and the organizational levels, more in-depth investigation in this area is necessary [

39,

41,

44].

Two central work-related wellbeing indicators are work engagement and burnout [

45]. Work engagement is an emotional and cognitive state manifested in vigor, dedication, and absorption [

46]. While nurses’ pandemic-related stress and worries about their own health led to lower work engagement [

47], concerns about the wellbeing of patients predicted higher work engagement [

48,

49]. Consequently, since being exposed to a PMIE leads to feelings of guilt and shame, adversely affecting the self-concept, we can expect that concerns about oneself are stronger than for SMTs, especially due to the high autonomy thwarting in memories of PMIEs [

12]. Thus, after perpetrating an SMT, morally upward counterfactuals help restore the person’s morally good self-concept [

12], guiding their future actions in that direction [

22]. This emphasizes reparatory actions toward the harmed patients, which should lead to higher work engagement. In contrast, memories of PMIEs are not followed by morally upward counterfactuals to the same extent due to higher autonomy thwarting, which blocks mental simulations of alternative future courses of action [

12,

22]. As such, it is likely that work engagement is lower in this case, since the focus of the concerns would be the person rather than the patients.

Burnout is a syndrome characterized by the constant experiencing of work-related stress, expressed through exhaustion, cynicism, negative work attitudes, and low professional efficacy [

50]. Having soared among nurses during this pandemic, it was predicted by nurses’ memories of self- and other-PMIEs, through basic psychological need thwarting [

12,

13,

51], which alone can have a negative effect on burnout for up to two years after the event [

52]. Turnover intentions were found to be the strongest predictor for turnover behavior, designating a conscious and deliberate willfulness to leave the workplace [

53]. They represent “the last in a sequence of withdrawal cognitions, a set to which thinking of quitting and intent to search for alternative employment also belong” [

54] (p. 262). Already higher in nursing [

44], they spiked during the COVID-19 pandemic [

55], being associated with memories of self-and other-PMIEs in this population [

13].

Previous research suggested that burnout and work engagement may be antecedents of nurses’ turnover intentions [

56,

57]. Burnout mediated the relationship between perceived organizational justice and respect, work values, fairness, appropriate recognition and compensation, and, respectively, turnover intentions [

58]. These workplace characteristics were previously linked to low relatedness satisfaction (i.e., low respect and fairness), low autonomy satisfaction (i.e., low perceived organizational justice), and low competence satisfaction (i.e., low recognition and compensation) [

17]. As such, burnout might mediate the relationships between need satisfaction and turnover intentions in our model [

58]. Low autonomy was associated with a decreased work engagement in nurses, as they found their jobs less meaningful and felt less responsible for their work, which was associated with higher turnover intentions [

56]. Work engagement also mediated the relationship between ethical leadership and decision authority, associated with lower competence and relatedness satisfaction [

58], and, respectively, turnover intentions [

56]: the more nurses felt connected to and respected by their leaders, and the more their merits were acknowledged fairly, the lower their turnover intentions [

57]. As such, work engagement might mediate the relationships between need satisfaction and turnover intentions in our model [

54,

55,

56,

57,

58].

1.5. Present Study

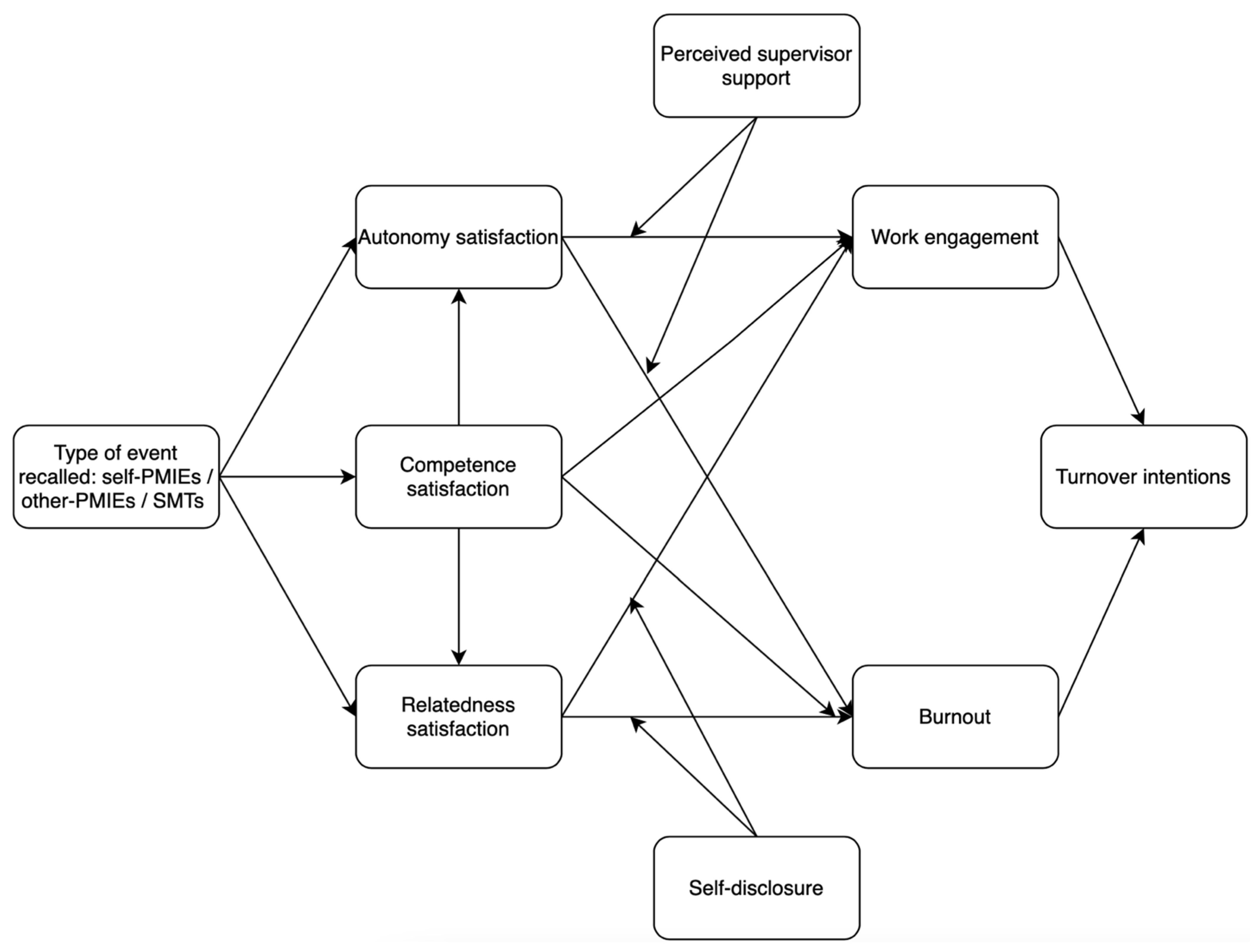

In our study, our first goal is to investigate whether other- and self-PMIEs may differently influence nurses’ occupational wellbeing and turnover intentions compared to SMTs, according to the thwarting of nurses’ basic psychological needs associated to each type of memory (

Figure 1). As such, we hypothesized:

H1: Autonomy will be more thwarted in memories of self-PMIEs than in memories of other-PMIEs and in memories of SMTs.

H2: Autonomy will be more thwarted in memories of other-PMIEs than in memories of SMTs.

H3: Competence will be more thwarted in memories of self-PMIEs and, respectively, in memories of SMTs compared to memories of other-PMIEs.

H4: Relatedness will be more thwarted in memories of other-PMIEs than in memories of self-PMIEs and in memories of SMTs.

H5: Relatedness will be more thwarted in memories of self-PMIEs than in memories of SMTs.

H6: Memories of self-PMIEs will be associated with lower work engagement, higher burnout, and more turnover intentions compared to memories of SMTs and other-PMIEs.

H7: Memories of other-PMIEs will be associated with lower work engagement, higher burnout, and more turnover intentions compared to memories of SMTs.

H8: Autonomy, competence, and relatedness thwarting will mediate the differences in burnout, turnover intentions, and work engagement between memories of self-PMIEs, other-PMIEs, and SMTs.

Our second aim was to investigate whether self-disclosure and perceived autonomy support may operate as protective factors against the influence of basic psychological need thwarting on nurses’ occupational wellbeing and turnover intentions. Thus, we hypothesized:

H9: Nurses with higher levels of perceived autonomy support would experience lower burnout and turnover intentions, and, respectively, higher work engagement, when their memories are highly autonomy-thwarting, compared to nurses with lower levels of perceived autonomy support.

H10: Nurses with higher levels of self-disclosure would experience lower burnout and turnover intentions, and, respectively, higher work engagement, when their memories are highly relatedness-thwarting, compared to nurses with lower levels of perceived autonomy support.

H11: Burnout and work engagement will mediate the relationships between the types of events recalled, competence, relatedness, and autonomy satisfaction, and, respectively, turnover intentions.

4. Discussion

The Romanian healthcare system was the most affected one in Europe during the fourth wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, in terms of the disproportion between resources of all types (e.g., medical supplies, understaffing, insufficient time for patient care) and number of patients requiring medical attention [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Previous research showed that this constituted a fertile ground for PMIEs [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. This study aimed to investigate the differential effects of Romanian nurses’ episodic memories of self- and other-PMIEs during the fourth wave of the COVID-19 pandemic compared to a control group on their occupational wellbeing and turnover intentions, according to basic psychological need thwarting, as well as two potential protective factors for these relationships: perceived supervisor support and self-disclosure. Building on previous studies comparing memories of self-PMIEs to other-PMIEs [

13] and memories of undifferentiated PMIEs to memories of SMTs [

12], we designed an experiment to better isolate the potential outcomes of nurses’ exposure to self-PMIEs from exposure to other-PMIEs, in line with past recommendations [

5,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Our results partially supported our initial hypotheses. The differences in turnover intentions between nurses who recalled memories of self- and other-PMIEs, compared to each other and to the control group, were associated with significant differences in autonomy, competence, and relatedness, which, in turn, were associated with differences in burnout and work engagement. Higher levels of self-disclosure operated as a protective factor for burnout and work engagement, by weakening the strength of their association with relatedness satisfaction and with turnover intentions. Higher perceived supervisor support also helped weaken the association between autonomy satisfaction and work engagement, but it did not have the same effect on burnout in our sample.

The COVID-19 pandemic constituted an unprecedented crisis for healthcare systems all around the world, dramatically impacting patientcare and the psycho-social health and functioning of healthcare professionals. As frontline workers, nurses were among the most affected social categories, especially in terms of exposure to PMIEs [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. This occurred because of the sudden ethical shift brought about by the pandemic: from nursing ethics, which include values from the patient-centered model of care, rooted in deontological ethics, to the public-health-centered approach, rooted in consequentialist ethics, adopted out of necessity during the pandemic [

94,

95,

96]. As such, the transition from morally valuing the life of each patient to maximizing the number of lives saved led to ethical conflicts, amounting to PMIEs in many instances [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Aside from moral injury, exposure to PMIEs may have long-term consequences on a multitude of (occupational) health indicators, many of which remain uninvestigated and unaddressed by specific interventions [

11,

15,

16]. Of these, the impact of the autobiographical episodic memories of self- and other-PMIEs should be of immediate concern, given that research suggests they might not have been integrated in autobiographical knowledge yet [

13].

Autobiographical knowledge refers to semantic information about the self-concept, informing us about who we are and how we should act. Episodic memories of events which are in stark contrast with what we already know about ourselves are difficult to integrate into autobiographical knowledge, but they can guide behavior and shape attitudes prior to integration as well [

64]. For nurses, integrating memories of PMIEs would change their self-concept and work identities, expanding the moral boundaries encompassing their schemas about patientcare and their roles in it [

13]. If they internalize such “lessons” from the pandemic, according to which they and their peers are capable of, for instance, prioritizing resources according to arbitrary (and sometimes, discriminatory) criteria e.g., age; [

95,

96], acts that were once inconceivable outside of crisis situations become possible in more ordinary times. This could result in a catastrophic setback from the model of patient-centered care in nursing.

Aside from organizational and systemic consequences, nurses integrating such morally dissonant identity elements would lead to dehumanization, dissociation mechanisms, and a wide array of pathological outcomes [

15,

16], which could also contribute to decreasing the quality of patientcare. Thus, as our findings show, both memories of self- and other-PMIEs were associated with significant decreases in work engagement and, respectively, increases in burnout and turnover intentions, compared to a control group, outcomes which contribute to poorer job performance [

97,

98]. To prevent and treat these consequences of nurses’ exposure to self- and other-PMIEs, we first have to better distinguish the unique effects of each on occupational wellbeing and turnover intentions, and to identify the mechanisms through which the memories of these events negatively affect these outcomes. This would expand our search for potential paths of intervention, from reconstructing memories to addressing the basic psychological need thwarting through which they might impair nurses’ occupational wellbeing and turnover intentions.

Nurses’ memories of self-PMIEs were associated with lower work engagement, higher burnout, and more turnover intentions compared to both memories of other-PMIEs and memories of SMTs. Furthermore, memories of other-PMIEs were also associated with a similar decrease in nurses’ occupational wellbeing and, respectively, increase in turnover intentions compared to SMTs. These results support previous findings which showed that self-PMIEs have more negative effects on psychological health and functioning compared to other-PMIEs [

5,

13,

15,

16], in contrast to research showing similar effects for these two types of PMIEs [

14].

However, these events thwarted basic psychological needs differently. While autonomy satisfaction was lower in memories of both self- and other-PMIEs compared to the control group, it was most thwarted for memories of self-PMIEs, which significantly mediated the associations with burnout, work engagement, and turnover intentions. Competence satisfaction, on the other hand, was highest in memories of other-PMIEs and lowest in memories of self-PMIEs and SMTs. Finally, relatedness satisfaction was lowest in memories of other-PMIEs compared to memories of SMTs and memories of self-PMIEs, but lower for self-PMIEs than for SMTs. This implies that autonomy thwarting could be the main mechanism through which exposure to self-PMIEs may affect long-term psycho-social functioning and health in nurses, while relatedness thwarting could play this role for exposure to other-PMIEs. Finally, nurses feeling ineffective and inefficacious following exposure to self-PMIEs is comparable to the deficits in competence satisfaction occurring after they committed an SMT at their workplace. From an intervention standpoint, this result would indicate that strategies such as the ones used for overcoming medical errors could be efficient in addressing competence thwarting following exposure to self-PMIEs.

Nurses’ experience of medical errors is arguably more complex compared to other healthcare providers due to their increased contact with patients, which often puts them in problematic situations after a medical error occurs [

99]. Results of a systematic review suggest that disclosing medical errors to patients and family members enabled nurses to feel relief and closure, helping them to emotionally reconcile the event by taking the morally responsible action [

100]. Organizational formal support and informal support from colleagues helped them restore personal integrity and implement constructive changes [

101]. Future studies should investigate whether these two strategies could help restore nurses’ sense of competence following self-PMIEs, although disclosing such events as medical errors to patients would mean taking full responsibility for them, which could be problematic, because of the autonomy thwarting associated with self-PMIEs. Considering that they perpetrated those events under perceived external coercion, future studies should test disclosure to patients as a joint endeavor of the medical staff to alleviate nurses’ distress.

For the impact of the deficits in autonomy satisfaction associated with both memories of self- and other-PMIEs on our outcomes, we tested perceived supervisor support as a protective factor. Our results show that it operated as a protective factor against a decrease in work engagement for other-PMIEs, and against increases in turnover intentions for self- and other-PMIEs, without contributing to lowering burnout. Having a higher general level of perceived supervisor support could have helped nurses understand that the autonomy thwarting experienced during the self- and other-PMIEs (and associated with their memories of them) are not representative for their workplace and relationship with their supervisors outside of the crisis created by the COVID-19 pandemic. As such, in line with previous research, higher perceived supervisor support lowered the impact of autonomy thwarting on their turnover intentions [

30,

32]. This implies that interventions focused on increasing perceived supervisor support could help prevent and, possibly, restore the increase in nurses’ turnover intentions, attributable to exposure to self- and other-PMIEs during the COVID-19 pandemic. This also suggests that increasing perceived supervisor support could prevent the integration of these memories in nurses’ autobiographical knowledge.

On the other hand, perceived supervisor support did not protect against autonomy thwarting for any of the three groups. One possible explanation could be that burnout is considered a more complex syndrome, which severely affects occupational health, with some arguing it should be included as a distinct mental disorder in the current diagnostic system [

102]. In contrast, work engagement is a positive, affective-motivational state of fulfillment, characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption [

46], without pathological elements [

103]. Higher levels of self-disclosure can have therapeutic properties, as people usually act on their tendency to share their emotional experiences with others, whereas perceived supervisor support is more descriptive of work relationships. This might explain why higher self-disclosure was a significant moderator in our model for burnout, but not for perceived supervisor support.

Unlike perceived supervisor support, which is a result of previous experiences, to a certain extent, self-disclosure is a process of communication in which one naturally engages intentionally, with the purpose of sharing information about themselves and meaningful life events [

34]. Previous studies suggest that self-disclosure leads to decreased loneliness [

104,

105], aiding people to perceive their contexts as empathic, helpful, and affirmative [

106]. Thus, in opposition to perceived supervisor support, which describes a previous mode of relating, self-disclosure could have helped nurses experience social support

after being exposed to PMIEs, and thus exert a reparatory influence. Our results on self-disclosure are in line with past research, which showed that recovery from moral injury was associated with seeking out social support [

107] and reconnection activities [

108]. This could also occur because sharing one’s experience could help them find redemptive meaning in these traumatic events, an ability essential for healing and moving past a PMIE [

107,

108,

109]. In contrast, perceived lack of support following PMIEs led to sustained psychological distress and to the reinforcement of veterans’ sense of moral injury [

110,

111].

The stronger influence of self-disclosure for self-PMIEs can also be explained by past findings. Since self-PMIE exposure was associated with intense shame and guilt [

15,

16], disclosing personal information could open new perspectives about the self and the PMIE, fostering the construction of more affirmative narratives of the events [

36]. Thus, self-disclosing emotions and information about a PMIE could help adaptive coping by moving from distrust and betrayal to bonding, trust, and empowerment [

111].

Our research is not without limitations. Our research was cross-sectional, and we cannot derive any definitive conclusions regarding causality. Future studies should test our results longitudinally. Our sample was not representative of the population of Romanian nurses, although we aimed to collect data from nurses from various specialties. Furthermore, future studies should also explore the content of nurses’ memories of self- and other-PMIEs from the COVID-19 pandemic thematically. Although it would have enriched our research to have participants permit us to employ their data for this purpose, they did not agree, due to its delicate nature. Future studies should aim to achieve this purpose. Finally, we conducted three separate studies in 2022 (including the present study) in which we explored associations between Romanian nurses’ autobiographical episodic memories from the COVID-19 pandemic and several occupational health outcomes. For all three, we employed snowballing sampling. We first contacted participants who took part in previous studies on different topics and invited them to: (a) participate in the current study; and (b) to contact other potential participants from their personal networks who met the eligibility criteria. Since we extended this invitation for all three studies, we may have had people who took part in all three of them, which might have led to their becoming familiar with the purpose of our studies, since they were debriefed after each one. It should also be noted that their personal contacts may have shared socio-demographic characteristics with them, since they were more likely to contact friends/colleagues of similar age and background. This might have decreased the heterogeneity of our samples, but also the external validity of our findings. Future studies should test our results in different geo-cultural settings and on representative samples of nurses.