Gender Inequality in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Associations with Parental Physical Abuse and Moderation by Child Gender

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Gender Inequality in LMICs

1.2. Parental Physical Abuse in LMICs

1.3. Gender Inequality and Parental Physical Abuse

1.4. Possible Differences by Child Gender

1.5. The Present Study

2. Methods

2.1. Data and Sample

2.2. Measures

2.3. Analytic Approach

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Association between Gender Inequality and Physical Abuse

4.2. Association of Gender Inequality and Physical Abuse by Child Gender

4.3. Implications for Policy and Practice

4.4. Limitations and Considerations for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Development Programme. Gender Inequality Index (GII). 2022. Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/thematic-composite-indices/gender-inequality-index#/indicies/GII (accessed on 11 June 2022).

- Phinney, A.; de Hovre, S. Integrating human rights and public health to prevent interpersonal violence. Health Hum. Rights 2003, 6, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yodanis, C.L. Gender inequality, violence against women, and fear: A cross-national test of the feminist theory of violence against women. J. Interpers. Violence 2004, 19, 655–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, E.G.; Dahlberg, L.L.; Mercy, J.A.; Zwi, A.B.; Lozano, R. (Eds.) World Report on Violence and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

- Klevens, J.; Ports, K.A. Gender inequity associated with increased child physical abuse and neglect: A cross-country analysis of population-based surveys and country-level statistics. J. Fam. Violence 2017, 32, 799–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayachandran, S. The roots of gender inequality in developing countries. Annu. Rev. Econ. 2015, 7, 63–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klasen, S. What explains uneven female labor force participation levels and trends in developing countries? World Bank Res. Obs. 2019, 34, 161–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. How Low-Income Countries Are Closing Their Gender Gap. 2015. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2015/12/poorer-countries-close-gender-gap/ (accessed on 10 July 2022).

- Bauserman, M.; Lokangaka, A.; Thorsten, V.; Tshefu, A.; Goudar, S.S.; Esamai, F.; Garces, A.; Saleem, S.; Pasha, O.; Patel, A.; et al. Risk factors for maternal death and trends in maternal mortality in low- and middle-income countries: A prospective longitudinal cohort analysis. Reprod. Health 2015, 12, S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Say, L.; Chou, D.; Gemmill, A.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Moller, A.-B.; Daniels, J.; Gülmezoglu, A.M.; Temmerman, M.; Alkema, L. Global causes of maternal death: A WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2014, 2, E323–E333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Adolescent Pregnancy. 31 January 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-pregnancy (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- World Health Organization. Adolescent Pregnancy Factsheet. 2014. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112320/1/WHO_RHR_14.08_eng.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2015).

- World Health Organization. Maternal Mortality. September 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality (accessed on 10 July 2022).

- Engle, P.L.; Fernald, L.C.; Alderman, H.; Behrman, J.; O′Gara, C.; Yousafzai, A.; Mello, M.C.; Hidrobo, M.; Ulkuer, N.; Ertem, I.; et al. Strategies for reducing inequalities and improving developmental outcomes for young children in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2011, 378, 1339–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congressional Research Service. Women in Globe National: Fact Sheet. April 2022. Available online: https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R45483.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2022).

- Doku, D.T.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Neupane, S. Associations of women’s empowerment with neonatal, infant and under-5 mortality in low- and /middle-income countries: Meta-analysis of individual participant data from 59 countries. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e001558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinda, E.M.; Rajkumar, A.P.; Enemark, U. Association between gender inequality index and child mortality rates: A cross-national study of 138 countries. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Children’s Fund. Gender Equality. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/gender-equality (accessed on 10 July 2022).

- Heise, L.L.; Kotsadam, A. Cross-national and multilevel correlates of partner violence: An analysis of data from population-based surveys. Lancet Glob. Health 2015, 3, e332–e340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willie, T.C.; Kershaw, T.S. An ecological analysis of gender inequality and intimate partner violence in the United States. Prev. Med. 2018, 118, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Violence against Women Prevalence Estimates, 2018; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Rafferty, Y. International dimensions of discrimination and violence against girls: A human rights perspective. J. Int. Womens Stud. 2013, 14, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. “Report of the Consultation on Child Abuse Prevention, 29–31 March 1999, WHO, Geneva,” no. WHO/HSC/PVI/99.1, 1999, [Online]. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/65900 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- United Nations Children’s Fund. Hidden in Plain Sight: A Statistical Analysis of Violence against Children; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/reports/hidden-plain-sight (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Lansford, J.E.; Deater-Deckard, K. Childrearing discipline and violence in developing countries. Child Dev. 2012, 83, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grogan-Kaylor, A.; Castillo, B.; Pace, G.T.; Ward, K.P.; Ma, J.; Lee, S.J.; Knauer, H. Global perspectives on physical and nonphysical discipline: A Bayesian multilevel analysis. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2021, 45, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, G.T.; Lee, S.J.; Grogan-Kaylor, A. Spanking and young children’s socioemotional development in low- and middle-income countries. Child Abus. Negl. 2018, 88, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The United Nations Children’s Fund. The State of the World’s Children 2007. 2006. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/reports/state-worlds-children-2007 (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Conger, R.D.; Donnellan, M.B. An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 175–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, M.A.R.; Conger, R.D. The role of economic pressure in the lives of parents and their adolescents: The Family Stress Model. In Negotiating Adolescence in Times of Social Change; Crockett, L.J., Silbereisen, R.K., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 201–223. [Google Scholar]

- Conger, R.D.; Conger, K.J.; Martin, M. Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. J. Marriage Fam. 2010, 72, 685–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, E.J.; Font, S.A. Housing insecurity, maternal stress, and child maltreatment: An application of the family stress model. Soc. Serv. Rev. 2015, 89, 9–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, A.; Bott, S.; Garcia-Moreno, C.; Colombini, M. Bridging the gaps: A global review of intersections of violence against women and violence against children. Glob. Health Action 2016, 9, 31516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, C.M.; Cutright, P. Structural and cultural determinants of child homicide: A cross-national snalysis. Violence Vict. 1994, 9, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, L.; Straus, M.A.; Jaffee, D. Legitimate violence, violent sttitudes, and rape: A test of the cultural spillover theory. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1988, 528, 79–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klevens, J.; Ports, K.A.; Austin, C.; Ludlow, I.J.; Hurd, J. A cross-national exploration of societal-level factors associated with child physical abuse and neglect. Glob. Public Health 2017, 13, 1495–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firebaugh, G. Ecological Fallacy, Statistics of. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences; Smelser, N.J., Baltes, P.B., Eds.; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 4023–4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabe-Hesketh, S.; Skrondal, A. Multilevel and Longitudinal Modeling Using Stata, 3rd ed.; Stata Press Publication: College Station, TX, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Akmatov, M.K. Child abuse in 28 developing and transitional countries—Results from the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 40, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Children’s Fund. Gender Equality: Global Annual Results Report 2020; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, K.P.; Grogan-Kaylor, A.; Pace, G.T.; Cuartas, J.; Lee, S. Multilevel ecological analysis of the predictors of spanking across 65 countries. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e046075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.; Boyle, E.H. Disciplinary practices among orphaned children in Sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoltenborgh, M.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; Van Ijzendoorn, M.H.; Alink, L.R.A. Cultural–geographical differences in the occurrence of child physical abuse? A meta-analysis of global prevalence. Int. J. Psychol. 2013, 48, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehlhausen-Hassoen, D. Gender-specific differences in corporal punishment and children’s perceptions of their mothers’ and fathers’ parenting. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP8176–NP8199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Straus, M.; Hamby, S.L.; Finkelhor, D.; Moore, D.W.; Runyan, D. Identification of child maltreatment with the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abus. Negl. 1998, 22, 249–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. World Development Indicators, “GDP per Capita (Current US$)”. 2022. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15; StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ai, C.; Norton, E.C. Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Econ. Lett. 2003, 80, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaca-Mandic, P.; Norton, E.C.; Dowd, B. Interaction terms in nonlinear models. Health Serv. Res. 2011, 47, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffrage, U.; Lindsey, S.; Hertwig, R.; Gigerenzer, G. Communicating statistical information. Science 2000, 290, 2261–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gigerenzer, G. What are natural frequencies? BMJ 2011, 343, d6386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudis, B.; Gandy, D. Waffle: Create Waffle Chart Visualizations. R Package Version 1.0.1. Available online: https://gitlab.com/hrbrmstr/waffle (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- United Nations General Assembly Resolution A/RES/70/1. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E (accessed on 14 January 2021).

- Lansford, J.E.; Godwin, J.; Tirado, L.M.U.; Zelli, A.; Al-Hassan, S.M.; Bacchini, D.; Bombi, A.S.; Bornstein, M.H.; Chang, L.; Deater-Deckard, K.; et al. Individual, family, and culture level contributions to child physical abuse and neglect: A longitudinal study in nine countries. Dev. Psychopathol. 2015, 27, 1417–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Grogan-Kaylor, A.C.; Pace, G.T.; Ward, K.P.; Lee, S.J. The association between spanking and physical abuse of young children in 56 low-and middle-income countries. Child Abus. Negl. 2022, 129, 105662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, J.S.; Freese, J. Regression Models for Categorical Dependent Variables Using Stata, 3rd ed.; Stata Press: College Station, TX, USA, 2014; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Cerna-Turoff, I.; Fang, Z.; Meierkord, A.; Wu, Z.; Yanguela, J.; Bangirana, C.A.; Meinck, F. Factors associated with violence against children in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-regression of nationally representative data. Trauma Violence Abus. 2021, 22, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, M.T.H.; Holton, S.; Romero, L.; Fisher, J. Polyvictimization among children and adolescents in low- and lower-middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abus. 2016, 19, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/ (accessed on 27 July 2022).

- Rosa, W. (Ed.) Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. In A New Era in Global Health; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. UN News. 7 March 2003. Available online: https://news.un.org/en/story/2003/03/61252-commemorating-womens-day-annan-calls-prioritizing-womens-needs (accessed on 19 June 2022).

| Variables | Mean or % | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver Physical Abuse | ||||

| No | 92.3 | |||

| Yes | 7.7 | |||

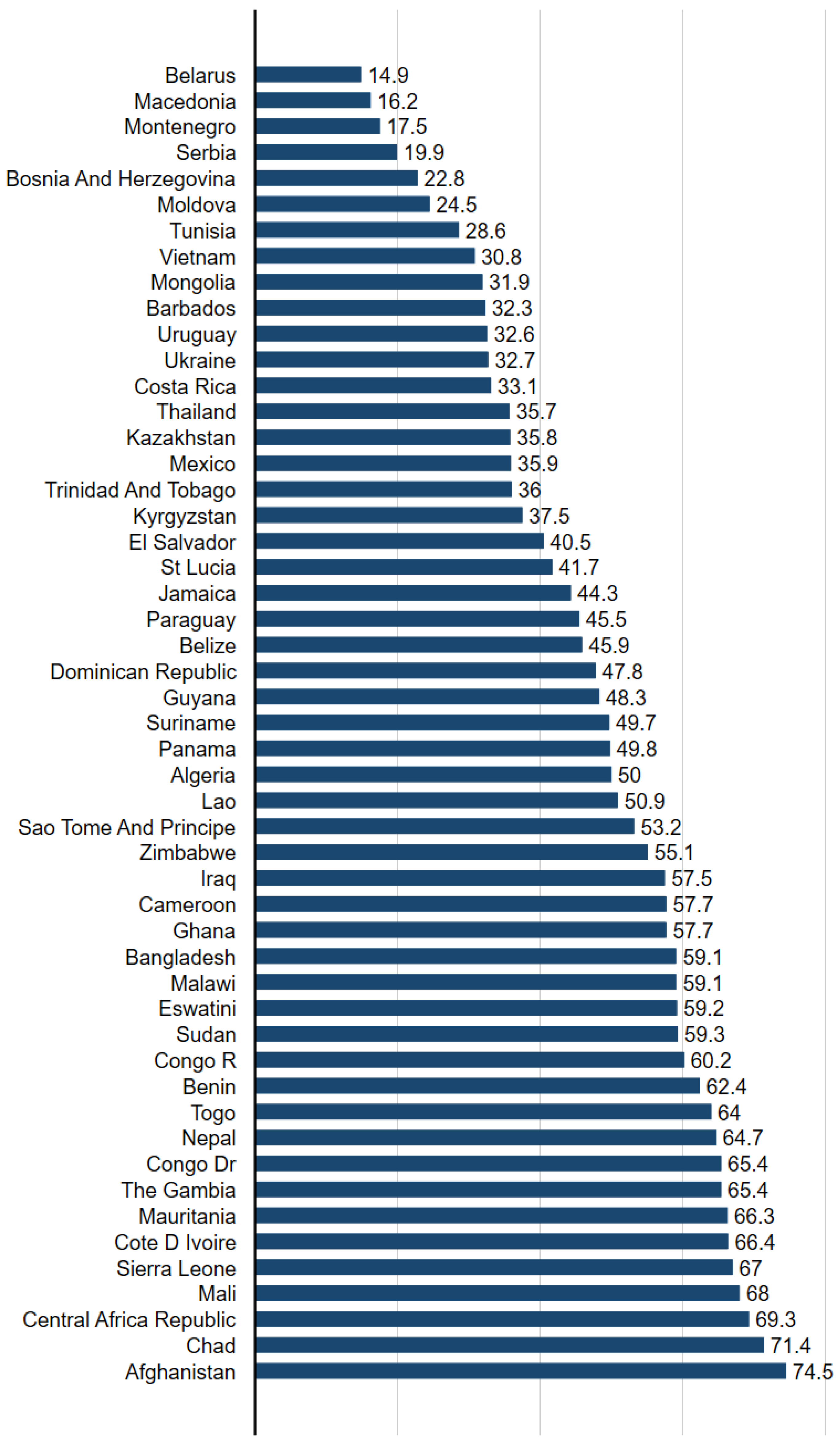

| Gender Inequality Index | 52.3 | 13.4 | 14.9 | 74.5 |

| GDP (1000 US$) | 3.48 | 3.20 | 0.33 | 19.03 |

| Physical Punishment is Necessary | ||||

| No | 79.8 | |||

| Yes | 16.6 | |||

| Don’t know/No opinion | 3.6 | |||

| Respondent is male | 73.2 | |||

| Respondent relationship with child | ||||

| Biological parent | 72.0 | |||

| Grandparent | 19.4 | |||

| Other | 8.6 | |||

| Respondent education | ||||

| None | 14.0 | |||

| Primary | 31.2 | |||

| Secondary or higher | 54.8 | |||

| Number of household members | 5.2 | 2.4 | 1 | 50 |

| Wealth Index | ||||

| Poorest | 20.3 | |||

| Second | 21.6 | |||

| Middle | 19.9 | |||

| Second Richest | 19.9 | |||

| Richest | 18.3 | |||

| Urban residence | 56.0 | |||

| MICS Round | ||||

| Round 4 | 45.3 | |||

| Round 5 | 54.7 | |||

| Child age (years) | 7.5 | 4.0 | 1 | 17 |

| Child is male | 52.2 |

| Predictors | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Household | Individual | Child Sex Moderation | |

| Gender Inequality Index | 1.051 *** | 1.048 *** | 1.042 *** | 1.038 *** |

| (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | |

| GDP (1000 USD) | 0.971 | 0.966 | 0.969 | 0.969 |

| (0.028) | (0.028) | (0.027) | (0.027) | |

| MICS Round 5 | 0.969 | 0.980 | 0.935 * | 0.935 * |

| (0.028) | (0.028) | (0.027) | (0.027) | |

| Wealth Quintile | ||||

| Second Poorest | 0.847 *** | 0.893 *** | 0.893 *** | |

| (0.011) | (0.012) | (0.012) | ||

| Middle | 0.780 *** | 0.850 *** | 0.850 *** | |

| (0.011) | (0.012) | (0.012) | ||

| Second Richest | 0.703 *** | 0.792 *** | 0.793 *** | |

| (0.011) | (0.013) | (0.013) | ||

| Richest | 0.586 *** | 0.713 *** | 0.714 *** | |

| (0.010) | (0.013) | (0.013) | ||

| Urban Residence | 1.108 *** | 1.116 *** | 1.116 *** | |

| (0.013) | (0.014) | (0.014) | ||

| Household Members | 1.031 *** | 1.034 *** | 1.034 *** | |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | ||

| Respondent Education (=None) | ||||

| Primary | 1.001 | 1.001 | ||

| (0.012) | (0.012) | |||

| Secondary + | 0.867 *** | 0.867 *** | ||

| (0.013) | (0.013) | |||

| Respondent is Male | 0.864 *** | 0.864 *** | ||

| (0.012) | (0.012) | |||

| Respondent is Biological Parent | ||||

| Grandparent | 0.770 *** | 0.769 *** | ||

| (0.011) | (0.011) | |||

| Other | 0.854 *** | 0.852 *** | ||

| (0.016) | (0.016) | |||

| Physical Punishment is Necessary (=No) | ||||

| Yes | 2.717 *** | 2.716 *** | ||

| (0.027) | (0.027) | |||

| Don’t know/No opinion | 1.658 *** | 1.658 *** | ||

| (0.046) | (0.046) | |||

| Child Age (Years) | 1.001 | 1.001 | ||

| (0.001) | (0.001) | |||

| Child is Female | 0.838 *** | 0.547 *** | ||

| (0.008) | (0.030) | |||

| GII × Female Child | 1.007 *** | |||

| (0.001) | ||||

| Constant | 0.011 *** | 0.012 *** | 0.018 *** | 0.021 *** |

| (0.005) | (0.006) | (0.008) | (0.010) | |

| Observations | 424,414 | 424,414 | 424,414 | 424,414 |

| Number of countries | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, J.; Grogan-Kaylor, A.C.; Lee, S.J.; Ward, K.P.; Pace, G.T. Gender Inequality in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Associations with Parental Physical Abuse and Moderation by Child Gender. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11928. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191911928

Ma J, Grogan-Kaylor AC, Lee SJ, Ward KP, Pace GT. Gender Inequality in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Associations with Parental Physical Abuse and Moderation by Child Gender. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):11928. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191911928

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Julie, Andrew C. Grogan-Kaylor, Shawna J. Lee, Kaitlin P. Ward, and Garrett T. Pace. 2022. "Gender Inequality in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Associations with Parental Physical Abuse and Moderation by Child Gender" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 11928. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191911928

APA StyleMa, J., Grogan-Kaylor, A. C., Lee, S. J., Ward, K. P., & Pace, G. T. (2022). Gender Inequality in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Associations with Parental Physical Abuse and Moderation by Child Gender. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 11928. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191911928