School Disengagement Predicts Accelerated Aging among Black American Youth: Mediation by Psychological Maladjustment and Moderation by Supportive Parenting

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Accelerated Aging Measure

1.2. Psychological Maladjustment as a Mediator

1.3. Supportive Parenting as a Moderator

1.4. Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Measures

2.3. Analytic Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive and Association Analysis

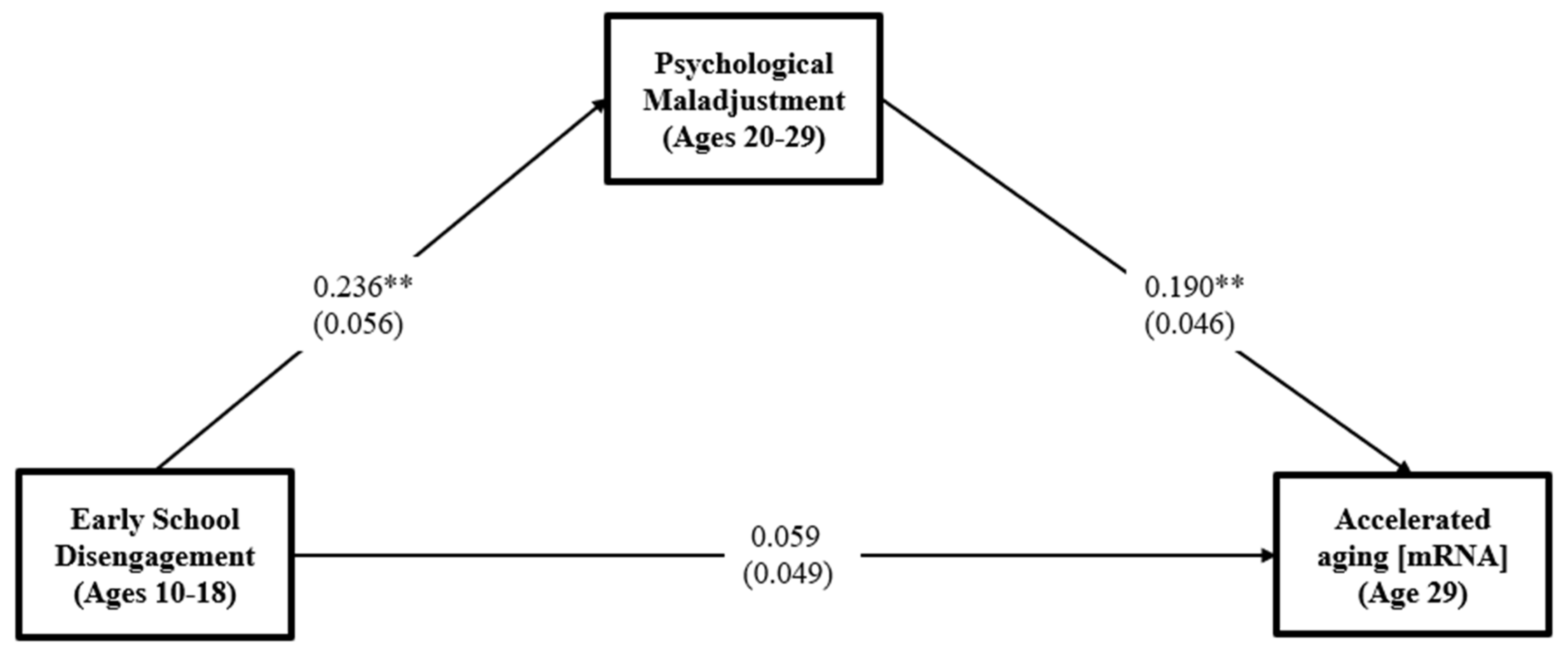

3.2. Test of Mediation Model

3.3. Test of Moderated Mediation Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gardiner, T. Supporting health and educational outcomes through school-based health centers. Pediatric Nurs. 2020, 46, 292–307. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, B.J.; Greene, A.C. Do health and education agencies in the United States share responsibility for academic achievement and health? A review of 25 years of evidence about the relationship of adolescents’ academic achievement and health behaviors. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 52, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, B.; Krohn, M.D. The effects of parental school exclusion on offspring drug use: An intergenerational path analysis. J. Crim. Justice 2020, 69, 101694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askeland, K.G.; Bøe, T.; Lundervold, A.J.; Stormark, K.M.; Hysing, M. The association between symptoms of depression and school absence in a population-based study of late adolescents. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Na, C. The consequences of school dropout among serious adolescent offenders: More offending? More arrest? Both? J. Res. Crime Delinq. 2017, 54, 78–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolf, S.H.; Johnson, R.E.; Phillips, R.L., Jr.; Philipsen, M. Giving everyone the health of the educated: An examination of whether social change would save more lives than medical advances. Am. J. Public Health 2007, 97, 679–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, G.H.; Yu, T.; Miller, G.E.; Chen, E. A family-centered prevention ameliorates the associations of low self-control during childhood with employment income and poverty status in young African American adults. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2020, 61, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinot, D.; Beaton, A.; Tougas, F.; Redersdorff, S.; Rinfret, N. Links between psychological disengagement from school and different forms of self-esteem in the crucial period of early and mid-adolescence. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2020, 23, 1539–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umberson, D.; Thomeer, M.B.; Williams, K.; Thomas, P.A.; Liu, H. Childhood adversity and men’s relationships in adulthood: Life course processes and racial disadvantage. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2016, 71, 902–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbu, J.U. Minority coping responses and school experience. J. Psychohist. 1991, 18, 433–456. [Google Scholar]

- Suglia, S.F.; Koenen, K.C.; Boynton-Jarrett, R.; Chan, P.S.; Clark, C.J.; Danese, A.; Faith, M.S.; Goldstein, B.I.; Hayman, L.L.; Isasi, C.R. Childhood and adolescent adversity and cardiometabolic outcomes: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018, 137, e15–e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.E.; Chen, E.; Parker, K.J. Psychological stress in childhood and susceptibility to the chronic diseases of aging: Moving toward a model of behavioral and biological mechanisms. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 137, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gonzalez, J.M.R.; Salas-Wright, C.P.; Connell, N.M.; Jetelina, K.K.; Clipper, S.J.; Businelle, M.S. The long-term effects of school dropout and GED attainment on substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016, 158, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.M. Long-term effect of adverse childhood experiences, school disengagement, and reasons for leaving school on delinquency in adolescents who dropout. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, J.; Fini, M.I.; Bailer, C.; Fritsch, R.; de Andrade, D.F. WWH-dropout scale: When, why and how to measure propensity to drop out of undergraduate courses. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2020, 13, 540–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cokley, K.; Moore, P. Moderating and mediating effects of gender and psychological disengagement on the academic achievement of African American college students. J. Black Psychol. 2007, 33, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, F.W.-M.; Zhou, H.; Harel-Fisch, Y. Hidden school disengagement and its relationship to youth risk behaviors: A cross-sectional study in China. Int. J. Educ. 2012, 4, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennison, C.R. Dropping out of college and dropping into crime. Justice Q. 2022, 39, 585–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazer, A.L.; Fite, P.J. Maternal psychological control, use of supportive parenting, and childhood depressive symptoms. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2016, 47, 384–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, J.A.; Colich, N.L.; Uddin, M.; Armstrong, D.; McLaughlin, K.A. Early experiences of threat, but not deprivation, are associated with accelerated biological aging in children and adolescents. Biol. Psychiatry 2019, 85, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambron, C.; Kosterman, R.; Catalano, R.F.; Guttmannova, K.; Herrenkohl, T.I.; Hill, K.G.; Hawkins, J.D. The role of self-regulation in academic and behavioral paths to a high school diploma. J. Dev. Life-Course Criminol. 2017, 3, 304–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, L.K.; Aghajani, M.; Clark, S.L.; Chan, R.F.; Hattab, M.W.; Shabalin, A.A.; Zhao, M.; Kumar, G.; Xie, L.Y.; Jansen, R. Epigenetic aging in major depressive disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 2018, 175, 774–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Miller, G.E.; Yu, T.; Chen, E.; Brody, G.H. Self-control forecasts better psychosocial outcomes but faster epigenetic aging in low-SES youth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015, 112, 10325–10330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafflin, K.; Pfeiffer, C.; Bergman, M.M. Effects of self-esteem and stress on self-assessed health: A Swiss study from adolescence to early adulthood. Qual. Life Res. 2019, 28, 915–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juang, L.P.; Silbereisen, R.K. Supportive parenting and adolescent adjustment across time in former East and West Germany. J. Adolesc. 1999, 22, 719–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, R.H.; Hall, J.; Cluver, L.; Meinck, F. Can supportive parenting protect against school delay amongst violence-exposed adolescents in South Africa? Child Abus. Negl. 2018, 78, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.J.; Joehanes, R.; Pilling, L.C.; Schurmann, C.; Conneely, K.N.; Powell, J.; Reinmaa, E.; Sutphin, G.L.; Zhernakova, A.; Schramm, K. The transcriptional landscape of age in human peripheral blood. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol. 2013, 14, 3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannum, G.; Guinney, J.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, L.; Hughes, G.; Sadda, S.; Klotzle, B.; Bibikova, M.; Fan, J.-B.; Gao, Y. Genome-wide methylation profiles reveal quantitative views of human aging rates. Mol. Cell 2013, 49, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jylhävä, J.; Pedersen, N.L.; Hägg, S. Biological age predictors. EBioMedicine 2017, 21, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, R.L.; Lei, M.-K.; Beach, S.R.; Simons, L.G.; Barr, A.B.; Gibbons, F.X.; Philibert, R.A. Testing life course models whereby juvenile and adult adversity combine to influence speed of biological aging. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2019, 60, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, K. Some social, psychological and educational aspects related to persistent school absenteeism. Res. Educ. 1984, 31, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsky, D.W.; Caspi, A.; Cohen, H.J.; Kraus, W.E.; Ramrakha, S.; Poulton, R.; Moffitt, T.E. Impact of early personal-history characteristics on the Pace of Aging: Implications for clinical trials of therapies to slow aging and extend healthspan. Aging Cell 2017, 16, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, K.L.; Knight, K.E.; Thornberry, T.P. School disengagement as a predictor of dropout, delinquency, and problem substance use during adolescence and early adulthood. J. Youth Adolesc. 2012, 41, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; He, H.; Yang, J.; Feng, X.; Zhao, F.; Lyu, J. Changes in the global burden of depression from 1990 to 2017: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 126, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvik, M.; Idsoe, T.; Bru, E. Depression and school engagement among Norwegian upper secondary vocational school students. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2014, 58, 592–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.K.; Brody, G.H.; Beach, S.R. Intervention effects on self-control decrease speed of biological aging mediated by changes in substance use: A longitudinal study of African American youth. Fam. Process 2021, 61, 659–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccio, C.M. Exploring potential protective factors for the relationship between low self-control in adolescence and negative health outcomes in adulthood. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2021, 65, 1559–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, M.G.; Salas-Wright, C.P.; Maynard, B.R. Dropping out of school and chronic disease in the United States. J. Public Health 2014, 22, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffitt, T.E.; Arseneault, L.; Belsky, D.; Dickson, N.; Hancox, R.J.; Harrington, H.; Houts, R.; Poulton, R.; Roberts, B.W.; Ross, S. A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011, 108, 2693–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakeri, H.; Karimpour, M. Parenting styles and self-esteem. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 29, 758–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeigler-Hill, V.; Wallace, M.T. Self-esteem instability and psychological adjustment. Self Identity 2012, 11, 317–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Song, Y.; Liu, J. The hippocampus underlies the association between self-esteem and physical health. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trzesniewski, K.H.; Donnellan, M.B.; Moffitt, T.E.; Robins, R.W.; Poulton, R.; Caspi, A. Low self-esteem during adolescence predicts poor health, criminal behavior, and limited economic prospects during adulthood. Dev. Psychol. 2006, 42, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamody, R.C.; Thurston, I.B.; Decker, K.M.; Kaufman, C.C.; Sonneville, K.R.; Richmond, T.K. Relating shape/weight based self-esteem, depression, and anxiety with weight and perceived physical health among young adults. Body Image 2018, 25, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batool, S.S. Academic achievement: Interplay of positive parenting, self-esteem, and academic procrastination. Aust. J. Psychol. 2020, 72, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumrind, D. Child care practices anteceding three patterns of preschool behavior. Genet. Psychol. Monogr. 1967, 75, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, E.A.; Chandler, M.; Heffer, R.W. The influence of parenting styles, achievement motivation, and self-efficacy on academic performance in college students. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2009, 50, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Ksinan, A.J.; Vazsonyi, A.T. Maternal support and deviance among rural adolescents: The mediating role of self-esteem. J. Adolesc. 2018, 69, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, A.S.; Criss, M.M.; Silk, J.S.; Houltberg, B.J. The impact of parenting on emotion regulation during childhood and adolescence. Child Dev. Perspect. 2017, 11, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, S.R.H.; Lei, M.K.; Brody, G.H.; Kim, S.; Barton, A.W.; Dogan, M.V.; Philibert, R.A. Parenting, SES-risk, and later young adult health: Exploration of opposing indirect effects via DNA methylation. Child Dev. 2016, 87, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, S.R.; Lei, M.K.; Brody, G.H.; Miller, G.E.; Chen, E.; Mandara, J.; Philibert, R.A. Smoking in young adulthood among African Americans: Interconnected effects of supportive parenting in early adolescence, proinflammatory epitype, and young adult stress. Dev. Psychopathol. 2017, 29, 957–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, S.R.; Lei, M.K.; Simons, R.L.; Barr, A.B.; Simons, L.G.; Ehrlich, K.; Brody, G.H.; Philibert, R.A. When inflammation and depression go together: The longitudinal effects of parent–child relationships. Dev. Psychopathol. 2017, 29, 1969–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, R.L.; Lei, M.-K.; Klopack, E.; Beach, S.R.; Gibbons, F.X.; Philibert, R.A. The effects of social adversity, discrimination, and health risk behaviors on the accelerated aging of African Americans: Further support for the weathering hypothesis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 282, 113169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, M.M.; Armenta, B.E. Trajectories of depressive symptoms among North American indigenous adolescents: Considering predictors and outcomes. Child Dev. 2020, 91, 932–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, P.C.; Wilcox, L.E. Self-control in children: Development of a rating scale. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1979, 47, 1020–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Coco, G.; Salerno, L.; Ingoglia, S.; Tasca, G.A. Self-esteem and binge eating: Do patients with binge eating disorder endorse more negatively worded items of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale? J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 77, 818–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, R.D.; Ge, X.; Elder, G.H., Jr.; Lorenz, F.O.; Simons, R.L. Economic stress, coercive family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Dev. 1994, 65, 541–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.-K.; Simons, R.L. The association between neighborhood disorder and health: Exploring the moderating role of genotype and marriage. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooten, N.N.; Pacheco, N.L.; Smith, J.T.; Evans, M.K. The accelerated aging phenotype: The role of race and social determinants of health on aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 73, 101536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K. Mplus User’s Guide. Version 8; Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, J.E.; Hamilton, M.A. The advantages of using standardized scores in causal analysis. Hum. Commun. Res. 2002, 28, 552–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J.F.; Richter, A.W. Probing three-way interactions in moderated multiple regression: Development and application of a slope difference test. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 917–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, M.E.; Crimmins, E.M. Evidence of accelerated aging among African Americans and its implications for mortality. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 118, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cohen, S. Psychosocial models of the role of social support in the etiology of physical disease. Health Psychol. 1988, 7, 269–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, M.-K.; Berg, M.T.; Simons, R.L.; Simons, L.G.; Beach, S.R. Childhood adversity and cardiovascular disease risk: An appraisal of recall methods with a focus on stress-buffering processes in childhood and adulthood. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 246, 112794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole-Lewis, Y.C.; Hope, E.C.; Mustafaa, F.N.; Jagers, R.J. Incongruent Impressions: Teacher, Parent, and Student Perceptions of Two Black Boys’ School Experiences. J. Adolesc. Res. 2021. Article ASAP. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, S.J.; Helaire, L.J.; Banerjee, M. Reflecting on racism: School involvement and perceived teacher discrimination in African American mothers. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2010, 31, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Accelerated Aging | — | ||||||||||

| 2. School Disengagement | 0.101 * | — | |||||||||

| 3. Psy Maladjustment | 0.185 ** | 0.244 ** | — | ||||||||

| 4. Supportive Parenting | −0.133 ** | −0.337 ** | −0.253 ** | — | |||||||

| 5. SEX (Male =1) | −0.090 † | 0.077 | −0.078 | 0.035 | — | ||||||

| 6. Healthy Diet | 0.029 | −0.043 | −0.068 | 0.052 | −0.162 ** | — | |||||

| 7. Exercise | −0.001 | 0.012 | −0.007 | 0.043 | 0.162 ** | 0.168 ** | — | ||||

| 8. Alcohol Consumption | −0.023 | 0.073 | 0.194 ** | −0.084 | 0.156 ** | 0.000 | 0.084 † | — | |||

| 9. Smoking | −0.135 ** | 0.011 | 0.108 * | 0.068 | 0.083 | −0.141 ** | 0.016 | 0.166 ** | — | ||

| 10. Education | −0.015 | −0.217 ** | −0.047 | −0.032 | −0.071 | 0.185 ** | 0.133 ** | 0.130* | −0.184 ** | ||

| 11. SES Risk | 0.034 | 0.032 | −0.039 | −0.039 | −0.050 | −0.022 | −0.010 | −0.090 | 0.135 ** | −0.307 ** | — |

| Mean | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.370 | 3.306 | 2.599 | 0.935 | 0.743 | 13.075 | 0.318 |

| SD | 2.972 | 1.000 | 2.435 | 1.000 | 0.484 | 1.240 | 1.159 | 1.249 | 1.480 | 1.724 | 0.205 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Accelerated Aging (age 29) | — | |||||

| 2. School Disengagement (age 10–18) | 0.101 * | — | ||||

| 3. Depression (age 22–29) | 0.139 ** | 0.122 * | — | |||

| 4. Lack of Self-Regulation (age 22–29) | 0.168 ** | 0.238 ** | 0.439 ** | — | ||

| 5. Low Self-Esteem (age 22–29) | 0.144 ** | 0.235 ** | 0.534 ** | 0.492 ** | — | |

| 6. Supportive Parenting (age 10–18) | −0.133 ** | −0.337 ** | −0.131 * | −0.186 ** | −0.300 ** | — |

| Mean | 0.000 | 0.000 | 2.102 | 16.047 | 8.975 | 0.000 |

| SD | 2.972 | 1.000 | 1.781 | 2.927 | 2.841 | 1.000 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ong, M.L.; Klopack, E.T.; Carter, S.; Simons, R.L.; Beach, S.R.H. School Disengagement Predicts Accelerated Aging among Black American Youth: Mediation by Psychological Maladjustment and Moderation by Supportive Parenting. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12034. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912034

Ong ML, Klopack ET, Carter S, Simons RL, Beach SRH. School Disengagement Predicts Accelerated Aging among Black American Youth: Mediation by Psychological Maladjustment and Moderation by Supportive Parenting. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12034. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912034

Chicago/Turabian StyleOng, Mei Ling, Eric T. Klopack, Sierra Carter, Ronald L. Simons, and Steven R. H. Beach. 2022. "School Disengagement Predicts Accelerated Aging among Black American Youth: Mediation by Psychological Maladjustment and Moderation by Supportive Parenting" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12034. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912034

APA StyleOng, M. L., Klopack, E. T., Carter, S., Simons, R. L., & Beach, S. R. H. (2022). School Disengagement Predicts Accelerated Aging among Black American Youth: Mediation by Psychological Maladjustment and Moderation by Supportive Parenting. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12034. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912034