Making It Work: The Experiences of Delivering a Community Mental Health Service during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Setting

2.2. Participants

2.3. Interview Method

2.4. Data Analysis

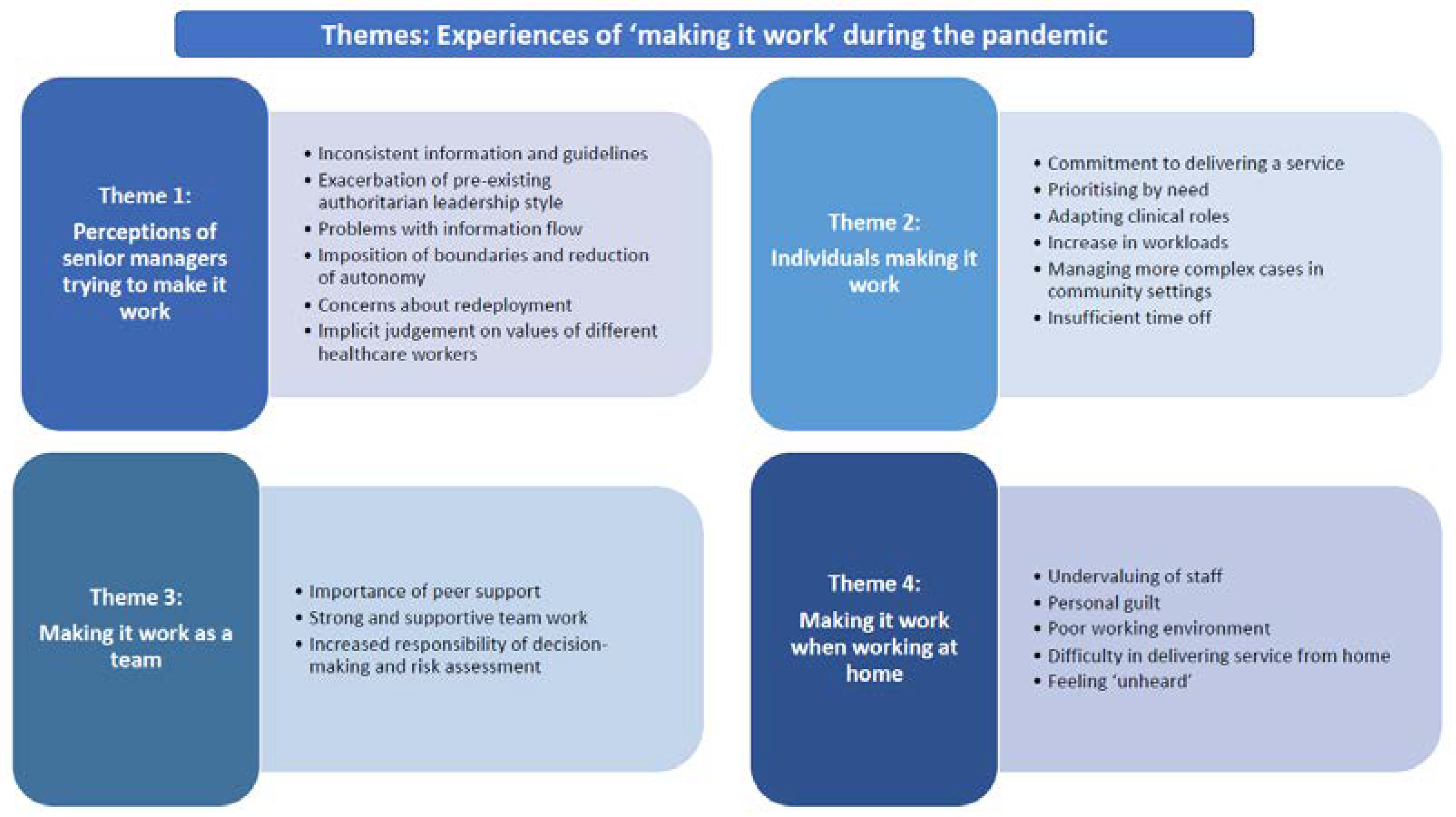

3. Results

3.1. Findings

3.2. Senior Trust Managers Trying to Make it Work

“what we did, we said things like, yes, it’s safe to do group work and we would tell people this at lunch time and then the Prime Minister would deliver his briefing erm an hour later saying people are no long permitted to meet in groups... so the very next morning we would have to contradict our message and so there was something about how we synchronised the advice to give people that undermined their confidence in us”(Respondent 015)

“…you would go from one meeting to the next and advice was changing constantly, so you were giving staff advice one minute and it was changing the next so trying to remember all that, that was quite difficult”(Respondent 021)

“You’re not being asked, you’re not being informed, you’re just gonna do what we [management] say, or not do, and there’s no reasoning behind it”.(Respondent 013)

“every decision that’s been made, everything’s being done without discussion, without asking anyone…, every morning, every afternoon, him and the other managers, they go into a side room, they’re there for a couple of hours, morning and afternoon, they come back out, decisions have been made, discussions have been had, we know nothing until something changes either in the off duty or you know, an email comes out saying this is going to happen”(Respondent 013)

“I don’t feel we are able to use our discretion with it to be honest with you because we’re being told that this is the trust policy, this is what we need to stick to”(Respondent 010)

“…now it’s been forced on them they say well why didn’t we do this in the first place!... they were just adamant that they would not let you work from home. And you know it just couldn’t be done and you know as soon as the COVID thing come, everyone’s working from home”(Respondent 001)

“It wasn’t put out there as a voluntary-as something that you could volunteer for, because we knew that no one basically would volunteer. So it came down as a management instruction from the senior management team in the local division, so that the instruction came down and then the instruction was to have a look at all your teams, look at the minimum amount of staff that you could work, that could maintain the team, and then anything that’s left over then would have to be redeployed”(Respondent 011)

“it caused a huge amount of upset, and there was people really fearful by going back onto the wards because at that point, every night on the news, all you had was news items on the ITUs and staff wearing full PPE [personal protective equipment] and deaths and the rising death toll, and staff who were being redeployed really did feel that they were being put at more risk by being redeployed into the inpatient wards”(Respondent 011)

“for us in the community, even though we’re seeing people are much as probably, you know, we’re seeing a high level of people, there still wasn’t any COVID testing for us…again, we were probably bottom of the chain you know, I think the ward staff, the mental health ward staff, they were all tested, which was rightly so. But for us in the community, we were not tested”(Respondent 009)

“what’s been really difficult as well, because doctors haven’t been going out at all to see patients only if they’ve had to, say, maybe section somebody or a very urgent review. But we’d still be expected to go out and see people... there was a little bit of kind of it was felt are they, their families more important than ours”(Respondent 021)

“we weren’t wearing any PPE in the office at that point we were just told to social distance of course our own common sense had told us by then to do that… Then 2 weeks ago we got guidance that we were all to wear masks, if we get up from our desk and move around the office we now have to wear masks…its little too late that to me”(Respondent 018)

“it’s not been their fault as such-is that the constant backtracking on decision making and that’s happened loads…, like we were hearing instructions coming from senior leadership but then at the five o’clock sort of briefings, Boris would be telling us sort of something else!”(Respondent 011)

3.3. Individuals Making It Work

“the reason you do the job is because we want to help… that’s why we do it, to try and help and for me to say, well sorry right now I can’t do that, and it’s not so good, but yeah I’m not comfortable about it, but I don’t think I should be put in that position either”(Respondent 004)

We’re trying, we’re doing the best that we can with limited resources and limited capability. There’s a lot of stuff that we’re not supposed to be doing, we get the guidelines, we do our best to follow them, of course they’re guidelines, they’re not rules so, if you need to take one or two shortcuts, for instance, so long as everything’s safe, then get on with it, you know? You’ve got to think generally, it’s the service user at the end of the day that needs the support.(Respondent 006)

“…so every visit that we do as community [staff], there’s got to be a rationale for why we’re doing that, what’s the urgency to that, what’s the crisis before we can make that decision to go out and ordinarily you would have made those decisions without passing it by any management, that’s what we would have just done as community nurses in the past”(Respondent 010)

“all I’m doing, all my role is limited to is delivering medication and prescriptions, shopping, and food bank parcels, there’s no kind of one-to-one support”.(Respondent 004)

“There’s 3 patients, really really high-risk patients that are waiting to go in for inpatient, they have a mental health act framework in place, but because there is not a single bed available, we’re trying to manage these risky patients in the community which is increasing a lot of kind of staff pressure and stress”(Respondent 008)

“The caseloads have remained the same within teams, but the workload for those practitioners who can still do face-to-face contacts, their workloads have increased, because they’ve had to take on other service users, because the other care coordinators have not been able to offer face-to-face contacts”(Respondent 011)

“so let’s say somebody was supposed to have an hour’s visit, for personal care, medication and meals, it’s then changed to task and go so basically, they went in, did whatever they had to do and get out as quick as they can. So people were having a reduction in the contact they were having each day.”(Respondent 002)

“I have had to kind of go above and beyond and I have had to adapt my depot clinic to a mobile depot clinic to go to the house in the morning as opposed to them coming in to clinic here, so it kind of has increased my case load in that respect ….so everyone’s kind of got an additional role for seeing people for the depots”.(Respondent 08)

“a lot of mine [service users] are actually at that point of discharge…at the moment I haven’t discharged them ‘cause at least they’ve got a point of contact but how long do I keep them on my caseload until I say, I’m sorry but you’re going now!”(Respondent 002)

“I’ve kind of very much been filling those gaps [in the service] …I haven’t had an opportunity to take any annual leave in those erm…well what is now 4 months”(Respondent 015)

3.4. Making It Work As a Team

“I have to say I’ve been pleasantly surprised at how well, you know, they’ve [management] adjusted to you know the new circumstances and the positivity and feeling that your work is appreciated.”(Respondent 001)

“I think we just as a team really quickly realised, you know, that we were going to have to do something before the lockdown really happened, so we did sort of address all of that, got rotas together and sort of everyone made a list of you know their vulnerable patients and things you know for the people that were on duty that would know about, so…I just felt it was quite well organised really, as a team”(Respondent 010)

“I suppose what we have here, is, I suppose is a very strong team and we cover for each other, and we are very supportive of each other, and I suppose we seem to sort of manage to get through somehow which we do which I think says a lot of the people I work with most definitely, very resourceful, very resilient despite everything.”(Respondent 012)

“I know we’re a good team and when I’ve needed someone to cover an injection because I’ve got other things there is always someone on my team, we’re a really good team so we can kind of support each other in that respect...”(Respondent 008)

“you actually miss that contact don’t you, with your team members…I mean I always find that a lot of my supervision is really informal, you know, you come back after a visit and you chat with one of your colleagues and say, have I done that right, have I made the right decision and you haven’t got that so it does feel quite isolating I think”(Respondent 010)

3.5. Making It Happen through Working at Home

“people who are in the shielding group, it was my understanding that regular contact should be made from somebody. I’ve, the only thing which has been keeping me up to speed with what’s happening with [Trust] is blogs and the Facebook pages (laughs)”(Respondent 014)

“People that haven’t been able to fulfil their role through no fault of their own through health issues or whatever you know have probably struggled more”(Respondent 018)

“I worry about people thinking that I’m not working my full hours or might be having a fine old time at home sort of thing…but I think that’s just my own concerns, not like management have been very strict over that”.(Respondent 010)

“So I think that’s been more of a problem so I think people are holding back really on sensitive information that normally they would have shared with us”(Respondent 010)

“I just didn’t see the, I didn’t see what good it was going to do, not seeing people and just phoning them, but as the weeks have gone on, I mean I’m phoning people I’ve never even met which is really hard ‘cause at least if you’ve met them, you can sort of see their home environment and you know what their care is like, but some of these people I’ve never actually met so you just phone them knowing nothing”.(Respondent 002)

“I know it’s my own fault, but I sit on the settee, which obviously isn’t a good place to sit all day long doing your work, but if you sit on the kitchen table that’s also quite uncomfortable”(Respondent 002)

“I just find it so boring just sat here on my own.”(Respondent 002)

“I’ve got really supportive managers and really supportive other colleagues, we have regular check ins with me, how are you doing? are you sure you’re ok? My manager and line manager both message me regularly, we’ve got a WhatsApp group that we chat on, we have emails off each other.”(Respondent 003)

“But I think I have got used to it and I have noticed that they do appreciate it and they need it, even if it is just a phone call.”(Respondent 002)

“people are feeling the Zooms aren’t appropriate to raise questions that they want to ask”(Respondent 013)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maben, J.; Bridges, J. COVID-19: Supporting nurses’ psychological and mental health. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 2742–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreffler, J.; Petrey, J.; Huecker, M. The Impact of COVID-19 on Healthcare Worker Wellness: A Scoping Review. West J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 21, 1059–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, J.; Balcom, C. Clinical leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic: Reflections and lessons learned. Healthcare Manag. Forum 2021, 34, 316–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schyve, P.M. Leadership in Healthcare Organizations: A Guide to Joint Commission Leadership Standards, a Governance Institute White Paper; Governance Institute: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yukl, G. Effective leadership behavior: What we know and what questions need more attention. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 26, 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarakoon, K. Leadership Styles for Healthcare. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2019, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hølge-Hazelton, B.; Kjerholt, M.; Rosted, E.; Thestrup Hansen, S.; Zacho Borre, L.; McCormack, B. Improving Person-Centred Leadership: A Qualitative Study of Ward Managers’ Experiences During the COVID-19 Crisis. Risk Manag. Healthcare Policy 2021, 14, 1401–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abualrub, R.F.; Gharaibeh, H.F.; Bashayreh, A.E. The relationships between safety climate, teamwork, and intent to stay at work among Jordanian hospital nurses. Nurs. Forum 2012, 47, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulop, L.; Mark, A. Relational leadership, decision-making and the messiness of context in healthcare. Leadership 2013, 9, 254–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Critical Preparedness, Readiness and Response Actions for COVID-19; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, C. Nurse leadership during a crisis: Ideas to support you and your team. Nurs. Times 2020, 116, 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Reicher, S.; Haslam, S.A.; Hopkins, N. Social identity and the dynamics of leadership: Leaders and followers as collaborative agents in the transformation of social reality. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 547–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, L.E. Trust: The Sublime Duty in Health Care Leadership. Health Care Manag. 2010, 29, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam-Webster Inc. Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 10th ed.; Merriam-Webster Inc.: Springfield, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Searle, R.; Skinner, D. New agendas and perspectives. In Trust and Human Resource Management; Searle, R., Skinner, D., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Berwick, D. Improving the Safety of Patients in England: National Advisory Group 17on the Safety of Patients in England; Department of Health: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fransen, K.; Haslam, S.A.; Steffens, N.K.; Vanbeselaere, N.; De Cuyper, B.; Boen, F. Believing in “us”: Exploring leaders’ capacity to enhance team confidence and performance by building a sense of shared social identity. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 2015, 21, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavel, J.J.V.; Baicker, K.; Boggio, P.S.; Capraro, V.; Cichocka, A.; Cikara, M.; Crockett, M.J.; Crum, A.J.; Douglas, K.M.; Druckman, J.N.; et al. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosser, E.; Westcott, L.; Ali, P.A.; Bosanquet, J.; Castro-Sanchez, E.; Dewing, J.; McCormack, B.; Merrell, J.; Witham, G. The Need for Visible Nursing Leadership During COVID-19. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2020, 52, 459–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobdell, K.W.; Hariharan, S.; Smith, W.; Rose, G.A.; Ferguson, B.; Fussell, C. Improving Health Care Leadership in the COVID-19 Era. NEJM Catal. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, G.; Gulati, K.; Sohal, A.; Spyridonidis, D.; Busari, J.O. Distributing systems level leadership to address the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Leader 2021, 6, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerada, C. Reflections on leadership during the Covid pandemic. Postgrad. Med. 2021, 133, 717–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, I.; Aurelio, M.; Gupta, A.; Blythe, J.; Khanji, M.Y. COVID-19: Causes of anxiety and wellbeing support needs of healthcare professionals in the UK: A cross-sectional survey. Clin. Med. 2021, 21, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemo, O.O.; Tu, S.; Keene, D. How to lead health care workers during unprecedented crises: A qualitative study of the COVID-19 pandemic in Connecticut, USA. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rücker, F.; Hårdstedt, M.; Rücker, S.C.M.; Aspelin, E.; Smirnoff, A.; Lindblom, A.; Gustavsson, C. From chaos to control—Experiences of healthcare workers during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic: A focus group study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahil Feroz, A.; Pradhan, N.A.; Hussain Ahmed, Z.; Shah, M.M.; Asad, N.; Saleem, S.; Siddiqi, S. Perceptions and experiences of healthcare providers during COVID-19 pandemic in Karachi, Pakistan: An exploratory qualitative study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e048984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catania, G.; Zanini, M.; Hayter, M.; Timmins, F.; Dasso, N.; Ottonello, G.; Aleo, G.; Sasso, L.; Bagnasco, A. Lessons from Italian front-line nurses’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative descriptive study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grailey, K.; Lound, A.; Brett, S. Lived experiences of healthcare workers on the front line during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative interview study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e053680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashcroft, R.; Donnelly, C.; Dancey, M.; Gill, S.; Lam, S.; Kourgiantakis, T.; Adamson, K.; Verrilli, D.; Dolovich, L.; Kirvan, A.; et al. Primary care teams’ experiences of delivering mental health care during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2021, 22, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, A.P.; Naumann, D.N.; O’Reilly, D. Mission command: Applying principles of military leadership to the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) crisis. BMJ Mil. Health 2021, 167, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boin, A.; Hart, P.’t.; Stern, E.; Sundelius, B. The Politics of Crisis Management: Public Leadership Under Pressure; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mealer, M.; Jones Rn, J. Methodological and ethical issues related to qualitative telephone interviews on sensitive topics. Nurse Res. 2014, 21, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic analysis. In Encyclopedia of Critical Psychology; Teo, T., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1947–1952. [Google Scholar]

- Sandman, P. Responding to Community Outrage: Strategies for Effective Risk Communication; American Industrial Hygiene Association: Falls Church, VA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Back, J.; Ross, A.J.; Duncan, M.D.; Jaye, P.; Henderson, K.; Anderson, J.E. Emergency department escalation in theory and practice: A mixed-methods study using a model of organizational resilience. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2017, 70, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvet, T.M.; Corbaz-Kurth, S.; Roos, P.; Benzakour, L.; Cereghetti, S.; Moullec, G.; Suard, J.-C.; Vieux, L.; Wozniak, H.; Pralong, J.A.; et al. Adapting to the unexpected: Problematic work situations and resilience strategies in healthcare institutions during the COVID-19 pandemic’s first wave. Saf. Sci. 2021, 139, 105277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J.; Ross, A.; Macrae, C.; Wiig, S. Defining adaptive capacity in healthcare: A new framework for researching resilient performance. Appl. Ergon. 2020, 87, 103111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorman, T. From command and control to modern approaches to leadership. ICU Manag. Pract. 2017, 17, 196–197. [Google Scholar]

- Ham, C. Improving the performance of health services: The role of clinical leadership. Lancet 2003, 361, 1978–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billings, J.; Ching, B.C.F.; Gkofa, V.; Greene, T.; Bloomfield, M. Experiences of frontline healthcare workers and their views about support during COVID-19 and previous pandemics: A systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensimon, C.M.; Tracy, C.S.; Bernstein, M.; Shaul, R.Z.; Upshur, R.E.G. A qualitative study of the duty to care in communicable disease outbreaks. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 65, 2566–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, P.A.; Benatar, S.R.; Bernstein, M.; Daar, A.S.; Dickens, B.M.; MacRae, S.K.; Upshur, R.E.; Wright, L.; Shaul, R.Z. Ethics and SARS: Lessons from Toronto. BMJ 2003, 327, 1342–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedetti, D.J.; Lewis-Newby, M.; Roberts, J.S.; Diekema, D.S. Pandemics and Beyond: Considerations When Personal Risk and Professional Obligations Converge. J. Clin. Ethics 2021, 32, 20–34. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Creating new solutions to tackle old problems: The first ever evidence-based guidance on emergency risk communication policy and practice. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 2018, 93, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wray, R.J.; Becker, S.M.; Henderson, N.; Glik, D.; Jupka, K.; Middleton, S.; Henderson, C.; Drury, A.; Mitchell, E.W. Communicating with the public about emerging health threats: Lessons from the Pre-Event Message Development Project. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 2214–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoia, E.; Lin, L.; Bernard, D.; Klein, N.; James, L.P.; Guicciardi, S. Public health system research in public health emergency preparedness in the United States (2009–2015): Actionable knowledge base. Am. J. Public Health 2017, 107, e1–e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Cities and Public Health Crises. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70465/WHO_HSE_IHR_LYON_2009.5_eng.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2022).

- Chung, B.P.M.; Wong, T.K.S.; Suen, E.S.B.; Chung, J.W.Y. SARS: Caring for patients in Hong Kong. J. Clin. Nurs. 2005, 14, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broom, J.; Broom, A.; Bowden, V. Ebola outbreak preparedness planning: A qualitative study of clinicians’ experiences. Public Health 2017, 143, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Burton, L.; Wall, A.; Perkins, E. Making It Work: The Experiences of Delivering a Community Mental Health Service during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12056. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912056

Burton L, Wall A, Perkins E. Making It Work: The Experiences of Delivering a Community Mental Health Service during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12056. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912056

Chicago/Turabian StyleBurton, Leanne, Abbie Wall, and Elizabeth Perkins. 2022. "Making It Work: The Experiences of Delivering a Community Mental Health Service during the COVID-19 Pandemic" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12056. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912056

APA StyleBurton, L., Wall, A., & Perkins, E. (2022). Making It Work: The Experiences of Delivering a Community Mental Health Service during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12056. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912056