Recovery Experiences Protect Emotionally Exhausted White-Collar Workers from Gaming Addiction

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Gaming Addiction

2.2.2. Recovery Experiences

2.2.3. Emotional Exhaustion

2.2.4. Demographics

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Bias

3.2. Preliminary Analyses

3.3. Bivariate Correlations

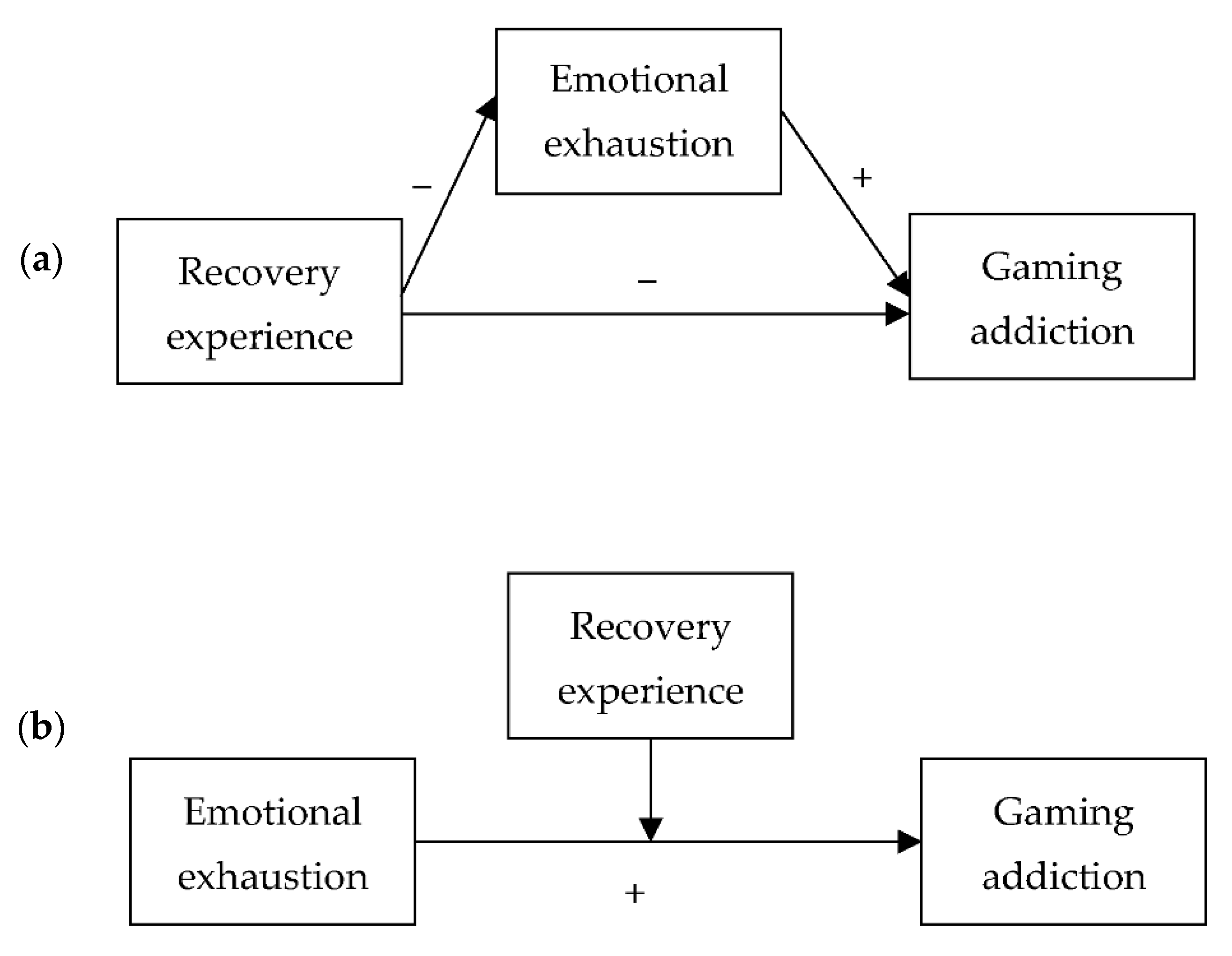

3.4. Testing the Indirect and Buffering Effects of Recovery Experiences

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wan, C.-S.; Chiou, W.-B. Why Are Adolescents Addicted to Online Gaming? An Interview Study in Taiwan. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2006, 9, 762–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization [WHO]. Gaming Disorder; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: http://www.who.int/features/qa/gaming-disorder/en/ (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Stevens, M.W.; Dorstyn, D.; Delfabbro, P.H.; King, D.L. Global prevalence of gaming disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2021, 55, 553–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altintas, E.; Karaca, Y.; Hullaert, T.; Tassi, P. Sleep quality and video game playing: Effect of intensity of video game playing and mental health. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 273, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.D. Internet gaming addiction: A systematic review of empirical research. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2012, 10, 278–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.; Ahsan, S.; Kiani, S.; Shahbaz, K.; Andleeb, S.N. Internet gaming, emotional intelligence, psychological distress, and academic performance among university students. Pak. J. Psychol. Res. 2020, 35, 253–270. [Google Scholar]

- Melodia, F.; Canale, N.; Griffiths, M.D. The role of avoidance coping and escape motives in problematic online gaming: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 20, 996–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Liu, T.; Liu, Y.; Hao, W.; Maurage, P.; Billieux, J. Prevalence and correlates of problematic online gaming: A systematic review of the evidence published in Chinese. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2018, 5, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohayon, M.M.; Roberts, L. Internet gaming disorder and comorbidities among campus-dwelling U.S. university students. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 302, 114043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEntee, A.; Kim, S.; Harrison, N.; Chapman, J.; Roche, A. Patterns and prevalence of daily tobacco smoking in Australia by industry and occupation: 2007–2016. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2021, 23, 2047–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKetta, S.; Prins, S.J.; Bates, L.M.; Platt, J.M.; Keyes, K.M. US trends in binge drinking by gender, occupation, prestige, and work structure among adults in the midlife, 2006–2018. Ann. Epidemiol. 2021, 62, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; Arlington, V.A., Ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, N.R.; Hwang, S.S.-H.; Choi, J.-S.; Kim, D.-J.; Demetrovics, Z.; Király, O.; Nagygyörgy, K.; Griffiths, M.D.; Hyun, S.Y.; Youn, H.C.; et al. Characteristics and psychiatric symptoms of Internet gaming disorder among adults using self-reported DSM-5 criteria. Psychiatry Investig. 2016, 13, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yu, S.; Mao, S.; Wu, A.M.S. The interplay among stress, frustration tolerance, mindfulness, and social support in Internet gaming disorder symptoms among Chinese working adults. Asia-Pac. Psychiatry 2018, 10, e12319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonnentag, S.; Fritz, C. The recovery experience questionnaire: Development and validation of a measure for assessing recuperation and unwinding from work. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 204–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Leiter, M.P. Maslach Burnout Inventory. In Evaluating Stress: A Book of Resources, 3rd ed.; Scarecrow Education: Lanham, MD, USA, 1997; pp. 191–218. [Google Scholar]

- Seidler, A.; Thinschmidt, M.; Deckert, S.; Then, F.; Hegewald, J.; Nieuwenhuijsen, K.; Riedel-Heller, S.G. The role of psychosocial working conditions on burnout and its core component emotional exhaustion—A systematic review. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2014, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sla, B. Physician burnout: A global crisis. Lancet 2019, 394, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Armon, G.; Melamed, S.; Toker, S.; Berliner, S.; Shapira, I. Joint effect of chronic medical illness and burnout on depressive symptoms among employed adults. Health Psychol. 2014, 33, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolatabadi, M.G. The mediating role of self-esteem in the relationship between social support with emotional exhaustion and psychological well-being. J. New Approaches Educ. Adm. 2021, 11, 151–170. [Google Scholar]

- Mikolajczak, M.; Brianda, M.E.; Avalosse, H.; Roskam, I. Consequences of parental burnout: Its specific effect on child neglect and violence. Child Abus. Negl. 2018, 80, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E.M.; Skaalvik, S. Dimensions of teacher burnout: Relations with potential stressors at school. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2017, 20, 775–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurm, W.; Vogel, K.; Holl, A.; Ebner, C.; Bayer, D.; Mörkl, S.; Szilagyi, I.-S.; Hotter, E.; Kapfhammer, H.-P.; Hofmann, P. Depression-burnout overlap in physicians. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, Y.; Hayes, J.A. Causes and consequences of burnout among mental health professionals: A practice-oriented review of recent empirical literature. Psychotherapy 2020, 57, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avci, D.K.; Sahin, H.A. Relationship between burnout syndrome and Internet addiction, and the risk factors in healthcare employees in a university hospital. Konuralp Med. J. Konuralp Tip Derg. 2017, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterka-Bonetta, J.; Sindermann, C.; Sha, P.; Zhou, M.; Montag, C. The relationship between Internet use disorder, depression and burnout among Chinese and German college students. Addict. Behav. 2019, 89, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pohl, M.; Feher, G.; Kapus, K.; Feher, A.; Nagy, G.D.; Kiss, J.; Fejes, É.; Horvath, L.; Tibold, A. The association of Internet addiction with burnout, depression, insomnia, and quality of life among Hungarian high school teachers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriwilai, K.; Charoensukmongkol, P. Face it, don’t facebook it: Impacts of social media addiction on mindfulness, coping strategies and the consequence on emotional exhaustion. Stress Health 2016, 32, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Stress, Culture, and Community: The Psychology and Philosophy of Stress; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnentag, S.; Natter, E. Flight attendants’ daily recovery from work: Is there no place like home? Int. J. Stress Manag. 2004, 11, 366–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meijman, T.F.; Mulder, G. Psychological Aspects of Workload. In A Handbook of Work and Organizational Psychology; Psychology Press: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen, A.; De Bloom, J.; Kinnune, U. Relationships between recovery experiences and well-being among younger and older teachers. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2020, 93, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Poulsen, M.G.; Poulsen, A.A.; Khan, A.; Poulsen, E.E.; Khan, S.R. Recovery experience and burnout in cancer workers in Queensland. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2015, 19, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, C.; Sonnentag, S. Recovery, health, and job performance: Effects of weekend experiences. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2005, 10, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fritz, C.; Sonnentag, S. Recovery, well-being, and performance-related outcomes: The role of workload and vacation experiences. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 936–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fauzi, M.F.M.; Yusoff, H.M.; Robat, R.M.; Saruan, N.A.M.; Ismail, K.I.; Haris, A.F.M. Doctors’ mental health in the midst of COVID-19 pandemic: The roles of work demands and recovery experiences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinecke, L. Games and recovery: The use of video and computer games to recuperate from stress and strain. J. Media Psychol. 2009, 21, 126–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lemmens, J.S.; Valkenburg, P.M.; Peter, J. Development and validation of a game addiction scale for adolescents. Media Psychol. 2009, 12, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 3rd ed.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 5th ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Harman, H.H. Modern Factor Analysis; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Egbert, J.; Plonsky, L. Bootstrapping techniques. In A Practical Handbook of Corpus Linguistics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 593–610. [Google Scholar]

- Vukosavljevic-Gvozden, T.; Filipovic, S.; Opacic, G. The mediating role of symptoms of psychopathology between irrational beliefs and internet gaming addiction. J. Ration. Emot. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2015, 33, 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahola, K.; Honkonen, T.; Pirkola, S.; Isometsä, E.; Kalimo, R.; Nykyri, E.; Aromaa, A.; Lönnqvist, J. Alcohol dependence in relation to burnout among the Finnish working population. Addiction 2006, 101, 1438–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; He, J.-Q.; Zou, J.-M.; Zhong, Y. Mobile phone addiction and its association with burnout in Chinese novice nurses: A cross-sectional survey. Nurs. Open 2021, 8, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, F.; Rega, V.; Boursier, V. Problematic Internet use and emotional dysregulation among young people: A literature review. Clin. Neuropsychiatry J. Treat. Eval. 2021, 18, 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Sechi, C.; Loi, G.; Cabras, C. Addictive Internet behaviors: The role of trait emotional intelligence, self-esteem, age, and gender. Scand. J. Psychol. 2021, 62, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fam, J.Y. Prevalence of Internet gaming disorder in adolescents: A meta-analysis across three decades. Scand. J. Psychol. 2018, 59, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, A.M.S.; Chen, J.H.; Tong, K.-K.; Yu, S.; Lau, J.T.F. Prevalence and associated factors of Internet gaming disorder among community dwelling adults in Macao, China. J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, A.A.; Bakker, A.B.; Field, J.G. Recovery from work-related effort: A meta-analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendsche, J.; Lohmann-Haislah, A. A meta-analysis on antecedents and outcomes of detachment from work. Front. Psychol. 2017, 7, 2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lu, L.; Chou, C.Y.; Cooper, C.L. Personal and social resources in coping with long hours of the Chinese work condition: The dual roles of detachment and social motivation. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 33, 1606–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Gehrman, P.R.; Liu, S.; Yang, F.; Ma, R.; Jia, Y.; Yang, X. Recovery experience as the mediating factor in the relationship between sleep disturbance and depressive symptoms among female nurses in Chinese public hospitals: A structural equation modeling analysis. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2020, 13, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vasiliu, O.; Vasile, D. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Internet gaming disorder and alcohol use disorder-A case report. Int. J. Psychol. Psychother. 2017, 2, 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, D.L.; Zhang, M.X.; Leong, K.K.; Wu, A.M.S. The predictive value of emotional intelligence for Internet gaming disorder: A 1-year longitudinal study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- González-Bueso, V.; Santamaría, J.J.; Fernández, D.; Merino, L.; Montero, E.; Ribas, J. Association between Internet gaming disorder or pathological video-game use and comorbid psychopathology: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gaming addiction | 12.63 | 4.46 | -- | |||||||||

| 2. Recovery experience-Detachment | 10.66 | 5.04 | 0.03 | -- | ||||||||

| 3. Recovery experience-Relaxation | 17.22 | 2.41 | −0.16 * | 0.29 *** | -- | |||||||

| 4. Recovery experience-Mastery | 15.61 | 3.14 | −0.07 | −0.12 | −0.07 | -- | ||||||

| 5. Recovery experience-Control | 17.32 | 2.77 | −0.18 ** | 0.11 | 0.39 *** | 0.07 | -- | |||||

| 6. Emotional exhaustion | 11.15 | 5.42 | 0.24 *** | 0.15 * | −0.13 # | −0.14 * | −0.41 *** | -- | ||||

| 7. Work hours | 45.00 | 10.39 | 0.03 | −0.10 | −0.13 | 0.08 | −0.16 * | 0.07 | -- | |||

| 8. Educational level | 4.92 | 0.60 | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.11 | −0.01 | 0.14 | −0.14 | -- | ||

| 9. Age ^ | 3.94 | 1.46 | −0.18 ** | −0.23 *** | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.05 | −0.06 | 0.10 | −0.15 * | -- | |

| 10. Sex ^^ | -- | -- | −0.19 ** | 0.05 | 0.05 | −0.16 * | 0.02 | −0.07 | −0.08 | 0.10 | −0.06 | -- |

| Direct Effect Size [95%CI] | Indirect Effect Size [95%CI] | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Detachment | 0.003 [−0.124, 0.963] | 0.031 [0.003, 0.077] |

| 2. Relaxation | −0.169 [−0.441, 0.224] | −0.010 [−0.083, 0.041] |

| 3. Mastery | −0.028 [−0.219, 0.764] | −0.024 [−0.078, 0.021] |

| 4. Control | −0.113 [−0.362, 0.370] | −0.128 [−0.241, −0.034] |

| Interaction Effect | R2change | Fchange | p | Interaction Effect Size | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Emotional exhaustion × Detachment | <0.001 | 0.06 | 0.80 | 0.002 | [−0.02, 0.02] |

| 2. Emotional exhaustion × Relaxation | 0.02 | 5.08 | 0.02 | −0.05 | [−0.09, −0.01] |

| 3. Emotional exhaustion × Mastery | <0.001 | 0.06 | 0.81 | −0.003 | [−0.12, 0.13] |

| 4. Emotional exhaustion × Control | 0.003 | 0.58 | 0.45 | −0.003 | [−0.13, 0.12] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, M.X.; Lam, L.W.; Wu, A.M.S. Recovery Experiences Protect Emotionally Exhausted White-Collar Workers from Gaming Addiction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912543

Zhang MX, Lam LW, Wu AMS. Recovery Experiences Protect Emotionally Exhausted White-Collar Workers from Gaming Addiction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912543

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Meng Xuan, Long W. Lam, and Anise M. S. Wu. 2022. "Recovery Experiences Protect Emotionally Exhausted White-Collar Workers from Gaming Addiction" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912543