Developing a Scale of Care Work-Related Quality of Life (CWRQoL) for Long-Term Care Workers in England

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

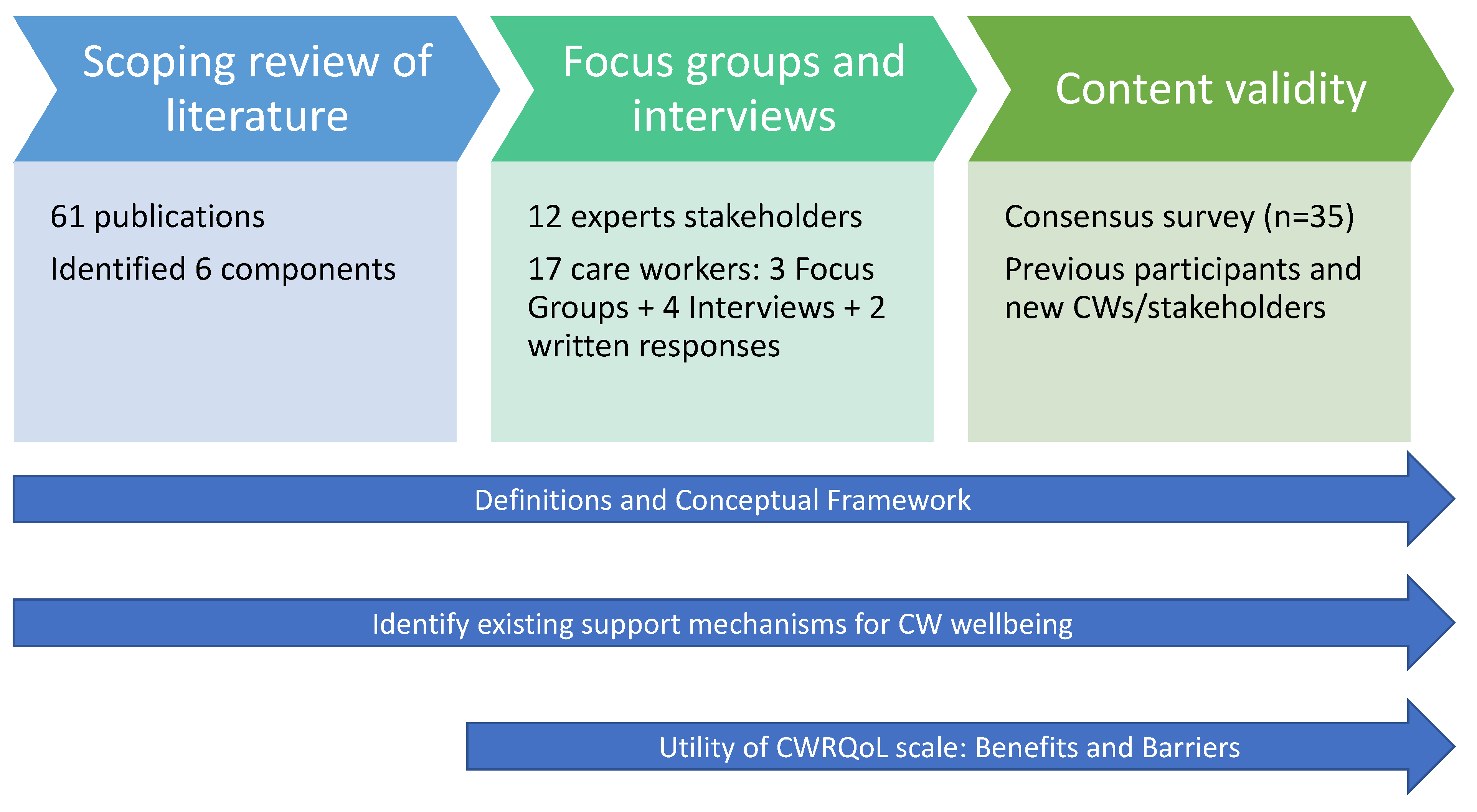

2.1. Overall Study Design

2.2. Data Generation Process

2.3. Analytical Approach

3. Results

3.1. Identifying the Domain and Sub-Domains Constituting the CWRQoL

Oh yes, definitely. And she’s on-call twenty-four seven, I mean you know that if you’ve on a night shift, you’ve got a problem at two o’clock in the morning, you just give her a ring. (Interview, care worker/manager, care home, female)

Yeah, I would like to progress up the career ladder. But I just feel like there isn’t really much career progression up the ladder. (FG interview, care worker, care home, male)

And in terms of autonomy and the decision making, again my experience of our company likes to have staff taking the initiative, of course always working within the same law and within the guidelines, always following the support plans. Still, the attitude is to always try to have staff which is proactive and they like to have staff taking initiatives and besides we are required to take the decision basically on an everyday or daily basis, and I don’t mind, I like it, I like it. (FG, care worker, community support, male)

Yeah, well, like MS3 and [MS] said, I think support workers need to be recognised more than the support workers we have. Yes, they are underpaid, and they are the ones doing it because they are ambitious and because they are caring. And some of them—yes, we all need money to live, but at some point, some of them are doing it because it’s rewarding for them. This is how they are here to care for people. And I do think like in an ideal world, they should be recognised more. (FG, manager, community support, male)

And because of—it is low paid, and obviously they are trying to get work anywhere—and like [MS2] said, they might take annual leave here and go and work somewhere else. I even know people that will do some shifts during the day and go and do a night shift, just to get the money, because it’s not enough of what they need to live. And yeah, I think it does affect them differently in a way where they just want to earn more and have a better living. (FG, manager, community support, male)

3.2. Utility of CWRQoL Scale

I think it will probably give a better insight for the leaders of those organisations if they really took it seriously. ‘Cos, you know, everybody works really hard in social care, so actually you very rarely take the time to stop and reflect and think about a different set of issues, so there’s a positive there. And it might forge better relationships between leadership and workforce, that might—and, you know, that is much needed, I think. (Stakeholder interviewee 04)

One of the things they will always say, “Oh, but each care home is different. Each care agency is different, so generalising is probably not a good idea, or benchmarking is not a good idea.” But then I think, well, all hospitals are different too, aren’t they? So, if we can do it in the hospital sector, the health sector, why can’t we do something similar for the social care sector as well? (Stakeholder interviewee 11)

3.3. Strategies to Support CWRQoL

- Staff surveys and feedback from senior management.

- Employee consultative committees for staff to raise issues with senior/executive management and human resources.

- Employee assistance programmes (confidential helplines, counselling and signposting to further resources and sources of help).

- Financial assistance for staff experiencing hardship during COVID-19.

3.4. The Potential Impact of COVID-19 on CWRQoL

Yeah, so, one of the things I’ve been trying to do is call social care workers, social care professionals, ‘cos the language, particularly at the moment ‘cos of COVID’, is about worker, right? That fails to recognise, I think, the kind of amount of skillsets that people actually have and they actually need to do their jobs, and that leads into that poor status and esteem that’s given to that role by society more generally but also, you know, they are a care worker, let’s send a care worker, rather than a social care professional. So, I think there’s an esteem issue that resonates with care workers, “I am just a care worker,” is what you’ll hear a lot. You know, “Nobody listens to me, I am just a care worker.” So, I think there’s an esteem issue that plays on people’s minds a bit and affects people’s quality of life (Stakeholder interview, Dementia charity, male)

“The fact that the public came out and ‘clapped for carers’ but then all of the attention went away and the care sector is now in a worse position than ever has been detrimental for many people in the sector and how they view themselves and their work.” (Survey respondent, 79980623)

“Although lip service was paid to carers in media (clap for carers etc.) we still feel completely forgotten and disparaged often by government.” (Survey respondent, 79999293)

4. Discussion

At a particular time, a care worker’s work-related quality of life corresponds to their experiences of work tasks and interactions, determined by and rewarded within an employment context in which interacting emotional, physical, social and financial components of wellbeing are impacted in work life and non-work life, and potentially shape their engagement with care.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Audit Office. The Adult Social Care Workforce in England; Department of Health and Social Care: London, UK, 2018. Available online: www.nao.org.uk/report/the-adult-social-care-workforce-in-england/ (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Bottery, S. How Covid-19 Has Magnified Some of Social Care’s Key Problems; The King’s Fund: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/covid-19-magnified-social-care-problems (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Bottery, S.; Varrow, M.; Thorlby, R.; Wellings, D. A Fork in the Road: Next Steps for Social Care Funding Reform. The Costs of Social Care Funding Options, Public Attitudes to Them-and the Implications for Policy Reform; The King’s Fund: London, UK, 2018; Available online: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/2018-05/A-fork-in-the-road-next-steps-for-social-care-funding-reform-May-2018.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Anderson, M.; O’Neill, C.; Clark, J.M.; Street, A.; Woods, M.; Johnston-Webber, C.; Charlesworth, A.; Whyte, M.; Foster, M.; Majeed, A.; et al. Securing a sustainable and fit-for-purpose UK health and care workforce. Lancet 2021, 397, 1992–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skills for Care. The State of the Adult Social Care Sector and Workforce in England; Skills for Care: Leeds, UK, 2021; Available online: www.skillsforcare.org.uk/stateof (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Hussein, S. Employment Inequalities among British Minority Ethnic Workers in Health and Social Care at the Time of COVID-19: A Rapid Review of the Literature. Soc. Policy Soc. 2022, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Migration Advisory Committee. Review of the Shortage Occupation List; MAC: London, UK, 2020. Available online: www.gov.uk/government/publications/review-of-the-shortage-occupation-list-2020 (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- McFadden, P.; Ross, J.; Moriarty, J.; Mallett, J.; Schroder, H.; Ravalier, J.; Manthorpe, J.; Currie, D.; Harron, J.; Gillen, P. The role of coping in the wellbeing and work-related quality of life of UK health and social care workers during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGilton, K.S.; Hall, L.M.; Wodchis, W.P.; Petroz, U. Supervisory support, job stress, and job satisfaction among long-term care nursing staff. JONA J. Nurs. Adm. 2007, 37, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braedley, S.; Owusu, P.; Przednowek, A.; Armstrong, P. We’re told, ‘suck it up’: Long-term care workers’ psychological health and safety. Ageing Int. 2018, 43, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, S. Job demand, control and unresolved stress within the emotional work of long-term care in England. Int. J. Care Caring 2018, 2, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harter, J.K.; Schmidt, F.L.; Keyes, C.L. Well-being in the Workplace and Its Relationship to Business Outcomes: A Review of the Gallup Studies. In Flourishing: Positive Psychology and the Life Well-Lived; Keyes, C.L.M., Haidt, J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; pp. 205–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cotton, P.; Hart, P.M. Occupational wellbeing and performance: A review of organisational health research. Aust. Psychol. 2003, 38, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redfern, S.; Hannan, S.; Norman, I.; Martin, F. Work satisfaction, stress, quality of care and morale of older people in a nursing home. Health Soc. Care Community 2002, 10, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zúñiga, F.; Ausserhofer, D.; Hamers, J.P.; Engberg, S.; Simon, M.; Schwendimann, R. Are staffing, work environment, work stressors, and rationing of care related to care workers’ perception of quality of care? A cross-sectional study. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 860–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brotheridge, C.; Grandey, A. Emotional labor and burnout: Comparing two perspectives of ‘people work’. J. Vocat. Behav. 2002, 60, 17–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spenceley, S.; Witcher, C.S.; Hagen, B.; Hall, B.; Kardolus-Wilson, A. Sources of moral distress for nursing staff providing care to residents with dementia. Dementia 2017, 16, 815–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, S. The English Social Care Workforce: The vexed question of low wages and stress. In The Routledge Handbook of Social Care Work around the World; Christensen, K., Billing, D., Eds.; Rutledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 74–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, S. Work Engagement, Burnout and Personal Accomplishments among Social Workers: A Comparison between Those Working in Children and Adults’ Services in England. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2018, 45, 911–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Costello, H.; Walsh, S.; Cooper, C.; Livingston, G. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence and associations of stress and burnout among staff in long-term care facilities for people with dementia. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2019, 31, 1203–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubery, J.; Grimshaw, D.; Hebson, G.; Ugarte, S.M. ‘It’s all about time’: Time as contested terrain in the management and experience of domiciliary care work in England. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 54, 753–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriarty, J.; Manthorpe, J.; Harris, J. Recruitment and Retention in Adult Social Care Services; King’s College: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, S.; Ismail, M.; Manthorpe, J. Changes in turnover and vacancy rates of care workers in England from 2008 to 2010: Panel analysis of national workforce data. Health Soc. Care Community 2016, 24, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stevens, M.; Sharpe, E.; Manthorpe, J.; Moriarty, J.; Hussein, S.; Orme, J.; Green-Lister, P.; Cavagnah, K.; McIntyre, G. Helping others or a rewarding career? Investigating student motivations to train as social workers in England. J. Soc. Work. 2012, 12, 16–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- England, K.; Dyck, I. Managing the body work of home care. Sociol. Health Illn. 2011, 33, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathaniel, A.K. A grounded theory of moral reckoning in nursing. Grounded Theory Rev. 2004, 4, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Danna, K.; Griffin, R.W. Health and well-being in the workplace: A review and synthesis of the literature. J. Manag. 1999, 25, 357–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, P. Wellbeing and the Workplace. In Wellbeing: Foundations of Hedonic Psychology; Kahneman, D., Schwarz, N., Eds.; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.; Leiter, M. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual; Consulting Psychologists Press: Mountain View, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2002, 6, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, E.; LePine, J.; Rich, B. Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delp, L.; Wallace, S.; Geiger-Brown, J.; Muntaner, C. Job Stress and Job Satisfaction: Home Care Workers in a Consumer-Directed Model of Care. Health Serv. Res. 2010, 45, 922–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilberforce, M.; Jacobs, S.; Challis, D.; Manthorpe, J.; Stevens, M.; Jasper, R.; Fernandez, J.-L.; Glendinning, C.; Jones, K.; Knapp, M.; et al. Revisiting the causes of stress in social work: Sources of job demands, control and support in personalised adult social care. Br. J. Soc. Work. 2014, 44, 812–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Woodhead, E.; Northrop, L.; Edelstein, B. Stress, social support, and burnout among long-term care nursing staff. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2016, 35, 84–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoenfisch, A.; Lipscomb, H.; Phillips, L. Safety of union home care aides in Washington State. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2017, 60, 798–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.; Lewis, J. Qualitative Research Practice; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Silarova, B.; Brookes, N.; Palmer, S.; Towers, A.M.; Hussein, S. Understanding and measuring the work-related quality of life among those working in adult social care: A scoping review. Health Soc. Care Community. 2022, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendonk, C.; Kaspar, R.; Bär, M.; Hoben, M. Improving Quality of Work life for Care Providers by Fostering the Emotional well-being of Persons with Dementia: A Cluster-randomized Trial of a Nursing Intervention in German long-term Care Settings. Dementia 2019, 18, 1286–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bielderman, A.; Nieuwenhuis, A.; Hazelhof, T.; van Gaal, B.G.I.; Schoonhoven, L.; Akkermans, R.P.; Gerritsen, D.L. Effects on staff outcomes and process evaluation of the educating nursing staff effectively (TENSE) program for managing challenging behavior in nursing home residents with dementia: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 120, 103982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Towers, A.M.; Palmer, S.; Brookes, N.; Markham, S.; Salisbury, S.; Silarova, B.; Mäkelä, P.; Hussein, S. Quality of Life at Work: What It Means for the Adult Social Care Workforce in England and Recommendations for Actions; Personal Social Services Research Unit: Kent, UK, under review.

- Bergers, G.P.A.; Marcelissen, F.H.G.; de Wolff, C.H. Vragenlijst Organisatie Stress-D Nijmegen; Vakgroep Arbeids: Leuven, Belgium, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Büssing, A.; Glaser, J.; Höge, T. Screening psychischer Belastungen in der stationären Krankenpflege (Belastungsscreening TAA-KH-S). Diagnostica 2001, 47, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreher, D.E.; Holloway, K.A.; Schoenfelder, E. The vocation identity questionnaire: Measuring the sense of calling. In Research in the Social Scientific Study of Religion; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 18, pp. 99–120. [Google Scholar]

- Willemse, B.M.; Smit, D.; de Lange, J.; Pot, A.M. Nursing home care for people with dementia and residents’ quality of life, quality of care and staff well-being: Design of the Living Arrangements for people with Dementia (LAD)-study. BMC Geriatr. 2011, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- National Association of Care and Support Workers. The Well-being of Professional Care Workers. 2018. Available online: http://www.nacas.org.uk/downloads/research/Well-being%20Research%20Report.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Salignac, F.; Hamilton, M.; Noone, J.; Marjolin, A.; Muir, K. Conceptualizing Financial Wellbeing: An Ecological Life-Course Approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2020, 21, 1581–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maben, J.; Peccei, R.; Adams, M.; Robert, G.; Richardson, A.; Murrells, T.; Morrow, E. Exploring the Relationship between Patients’ Experiences of Care and the Influence of Staff Motivation, Affect and Wellbeing; National Institute for Health Research: Southampton, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, S.; Saloniki, E.; Turnpenny, A.; Collins, G.; Vadean, F.; Bryson, A.; Forth, J.; Allan, S.; Towers, A.M.; Gousia, K.; et al. COVID-19 and the Wellbeing of the Adult Social Care Workforce: Evidence from the UK; The Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent: Canterbury, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristics | Focus Group Participants (n = 11), Focus Group Interviews (n = 4), Written Responses (n = 2) Total (n = 17) | Stakeholder Interviews (n = 12) | Consensus Survey (n = 35) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female, n = 8 Male, n = 9 | Female, n = 6 Male, n = 6 | Female, n = 29 Male, n = 6 |

| Job Role | Frontline care worker, n = 10, Care service manager, n = 6 Dual role care worker/manager, n = 1 | CEO, n = 2 Director of Operations, n = 1 Statistician, n = 1 People Experience Manager Independent Consultant and dignity adviser, n = 1 Trustee, n = 1 Director, n = 1 Director of Clinical Services, n = 1 Policy Director, n = 1 Project manager for evidence and impact, n = 1 Research Director, n = 1 Principal Lecturer and Programme Leader, n = 1 | Direct care role, n = 10 Managerial or supervisory role, n = 7 Care provider employer role, n = 3 Academic or researcher, n = 9 Registered professional, n = 4 Administrative or Support role, n = 2 Policy-maker, n = 2 Non-profit or charity based role, n = 4 Unemployed, n = 1 Other, n = 1 (NB survey respondents could identify with more than one role) |

| Organisation | Care home, n = 6 Community support, n = 10 Home care, n = 1 | Workforce organisation, n = 2 Government, n = 1 Charity, n = 4 Think tank. n = 1 National Homecare provider, n = 1 Telecare organisation, n = 1 Home care trade association, n = 1 University, n = 1 | |

| Years in Current Role | Mean = 3, min = 0, max = 12 Missing, n = 6 | M = 8, min = 1, max = 15 Missing, n = 1 | |

| Age | Mean = 40, min = 20, max = 55 Missing, n = 12 | - | 18–24 years, n = 2 25–34 years, n = 5 35–44 years, n = 5 45–54 years, n = 8 55–64 years, n = 10 ≥65 years, n = 5 |

| Ethnicity | White, n = 4 Other ethnic group, n = 1 Missing, n = 12 | ||

| User Group Cared for | Older adults (65+), n = 2 Adults of all ages with intellectual and developmental disabilities, n = 1 Younger adults (18–64) intellectual and developmental disabilities, n = 2 Missing, n = 12 | - |

| (a) | ||

| Domain and Sub-Domains/Items to be Included in the CWRQoL Scale and their Priorities | % | n |

| 1. Financial wellbeing (74%) | ||

| Financial wellbeing (enough money to meet your needs) | 69 | 24 |

| Pay and benefits | 46 | 16 |

| Job security | 46 | 16 |

| 2. Mental wellbeing * (54%) | ||

| 2.a Burnout/exhaustion | ||

| Feeling burnt out (unable to cope with work demands) | 77 | 27 |

| Impact of work on mental health (thoughts, feelings, mood) | 74 | 26 |

| Feeling emotionally exhausted at work | 74 | 26 |

| 2.b Satisfaction/motivation | ||

| Feeling a sense of satisfaction from helping others | 71 | 25 |

| Feeling motivated, enthusiastic or energised by work | 69 | 24 |

| 2.c Affected by loss of clients | ||

| Impact of grief when a client dies | 54 | 19 |

| 3. Features of the organisation/workplace (46%) | ||

| 3.a Staffing | ||

| Sufficient staffing | 80 | 28 |

| 3.b Management and supervision | ||

| Style of leadership and management | 77 | 27 |

| Feeling supported to do the job | 77 | 27 |

| Supervision arrangements | 40 | 14 |

| 3.c Working environment | ||

| Feelings of trust and safety within organisation | 74 | 26 |

| Physical work environment | 40 | 14 |

| 3.d Career development | ||

| Recognition of work achievements | 74 | 26 |

| Availability and access to training | 57 | 20 |

| Opportunities for learning and development | 51 | 18 |

| Having career progression options | 40 | 14 |

| 4. What care workers do in their jobs (46%) | ||

| 4.a Time | ||

| Time to appropriately perform care activities | 67 | 24 |

| Time for training | 63 | 22 |

| Working hours and shift pattern | 54 | 19 |

| Time for administrative work (e.g., documenting care) | 40 | 14 |

| 4.b Relations | ||

| Helping improve others’ quality of life | 66 | 23 |

| Developing relationships with clients | 51 | 18 |

| Feeling responsible for clients | 51 | 18 |

| Feedback from clients/families | 51 | 18 |

| Enabling clients to make their own decisions | 40 | 14 |

| 4.c Role & tasks | ||

| Clearly defined roles and responsibilities | 63 | 22 |

| Worrying about making mistakes | 54 | 19 |

| A sense of control over own activities | 51 | 18 |

| Variation in your work activities | 49 | 17 |

| Matching staff to the tasks they are good at | 49 | 17 |

| 4.d Care clients’ needs | ||

| Feeling overwhelmed by needs (e.g., behaviours that challenge) | 69 | 24 |

| Impact of caring for people at the end of life | 57 | 20 |

| 5. Impact of work on home-life * (34%) | ||

| Fatigue or other problems that limit what you do outside work | 77 | 27 |

| A positive mood from work that can improve your home-life | 60 | 21 |

| Work-related thoughts that stay with you off duty | 60 | 21 |

| 6. Professional identity as a care worker (26%) | ||

| 6.1 Feeling valued and respected | ||

| Feeling respected and valued by your employer | 77 | 27 |

| Feeling respected and valued by colleagues | 74 | 26 |

| Feeling respected and valued by clients | 71 | 25 |

| Feeling respected and valued by other professionals | 71 | 25 |

| Feeling respected and valued by the public | 60 | 21 |

| 6.2 Proud of profession | ||

| A sense of pride in your profession | 63 | 22 |

| 7. Physical wellbeing (20%) | ||

| Work-related physical injuries | 63 | 22 |

| Equipment to do the job | 51 | 18 |

| Impact of work on physical wellbeing (e.g., aches and pains) | 47 | 17 |

| Impact of work on healthy behaviours (e.g., eating, sleeping) | 47 | 17 |

| (b) | ||

| Sub-domains to be excluded from the CWRQoL scale: for which <40% respondents ‘Strongly Agree’ | % | n |

| Organisational characteristics | ||

| Rules and procedures | 26 | 9 |

| Job characteristics | ||

| Control over shifts and breaks | 26 | 9 |

| Spillover from work to home | ||

| Skills developed at work that can help in home-life | 31 | 11 |

| Stage 1: Inductive (Literature Review) | Stage 2: Deductive/Inductive (Qualitative Interviews) | Stage 3: Content Validity and Order of Importance (Consensus Survey) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domains | Sub-Domains | Domains | Sub-Domains | Domains | Sub-Domains | Items |

| Organisational Characteristics | Working Culture | Care organisation characteristics | Working environment | Features of care organisation (3) | Staffing | Vacancy rate; sufficient staff to client ratio |

| Working Climate | Staffing | Management and supervision | Style of leadership and management; Feeling supported to do the job; Supervision arrangements | |||

| Management and supervision | Working environment | Feelings of trust and safety within organisation; Physical work environment | ||||

| Diversity and inclusivity | Career development | Recognition of work achievements; Availability and access to training; Opportunities for learning & development; Having career progression options | ||||

| Career development | ||||||

| Rules and procedures | ||||||

| Job Characteristics | Job-person match | Nature of LTC work | Time | Nature of LTC work (4) | Time | Time to appropriately perform care activities; Time for training; Working hours and shift pattern; Time for administrative work (e.g., documenting care) |

| Autonomy/Control | Relations | Relations | Helping improve others’ quality of life; Developing relationships with clients; Feeling responsible for clients; Feedback from clients/families; Enabling clients to make their own decisions | |||

| Enough time to do the job | Roles and tasks | Roles and Tasks | Clearly defined roles and responsibilities; Worrying about making mistakes; A sense of control over own activities; Variation in your work activities; Matching staff to the tasks they are good at | |||

| Responsibility for people | Care client needs | Care client needs | Feeling overwhelmed by needs (e.g., behaviours that challenge); Impact of caring for people at the end of life | |||

| Learning and Growth | Control over shifts and breaks | |||||

| Mental wellbeing and health | Compassion Satisfaction | Mental Wellbeing | Burnout/exhaustion | Mental wellbeing (2) | Burnout/exhaustion | Feeling burnt out (unable to cope with work demands); Impact of work on mental health (thoughts, feelings, mood); Feeling emotionally exhausted at work |

| Burnout | Satisfaction and motivations | Satisfaction & motivations | Feeling a sense of satisfaction from helping others; Feeling motivated, enthusiastic or energised by work | |||

| Subjective experience of happiness | Affected by loss of client | Impact of grief when a client dies | ||||

| Physical Wellbeing and health | Work-related physical injuries | Physical wellbeing | Work-related physical injuries | Physical wellbeing (7) | Work-related physical injuries | |

| Equipment to do the job | Equipment to do the job | |||||

| Impact of work on physical wellbeing | Impact of work on physical wellbeing | |||||

| Impact of work on healthy behaviours | Impact of work on healthy behaviours | |||||

| Spill-over from work to home | Work related thoughts to stay off duty | Spill-over from work to home | Work related thoughts to stay off duty | Spill-over from work to home (5) | Fatigue or other problems that limit what you do outside work | |

| Skills developed at work that can help in home-life | Work related thoughts to stay off duty | |||||

| Fatigue or other problems that limit what you do outside work | A positive mood from work that can improve your home-life | |||||

| A positive mood from work that can improve your home-life | ||||||

| Professional identity | Professional identity | Valued and respected | Professional identity (6) | Valued and respected | Feeling respected and valued by your employer; Feeling respected and valued by colleagues; Feeling respected and valued by clients; Feeling respected and valued by other professionals; Feeling respected and valued by the public | |

| Proud of profession | Proud of profession | A sense of pride in your profession | ||||

| Financial wellbeing | Enough money to meet needs | Financial wellbeing (1) | Enough money to meet needs | |||

| Pay and benefits | Pay and benefits | |||||

| Job security | Job security | |||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hussein, S.; Towers, A.-M.; Palmer, S.; Brookes, N.; Silarova, B.; Mäkelä, P. Developing a Scale of Care Work-Related Quality of Life (CWRQoL) for Long-Term Care Workers in England. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 945. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020945

Hussein S, Towers A-M, Palmer S, Brookes N, Silarova B, Mäkelä P. Developing a Scale of Care Work-Related Quality of Life (CWRQoL) for Long-Term Care Workers in England. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(2):945. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020945

Chicago/Turabian StyleHussein, Shereen, Ann-Marie Towers, Sinead Palmer, Nadia Brookes, Barbora Silarova, and Petra Mäkelä. 2022. "Developing a Scale of Care Work-Related Quality of Life (CWRQoL) for Long-Term Care Workers in England" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 2: 945. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020945

APA StyleHussein, S., Towers, A.-M., Palmer, S., Brookes, N., Silarova, B., & Mäkelä, P. (2022). Developing a Scale of Care Work-Related Quality of Life (CWRQoL) for Long-Term Care Workers in England. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(2), 945. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020945