Time to End-of-Life of Patients Starting Specialised Palliative Care in Denmark: A Descriptive Register-Based Cohort Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Study Design and Setting

2.3. Data Sources

2.4. Variables

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

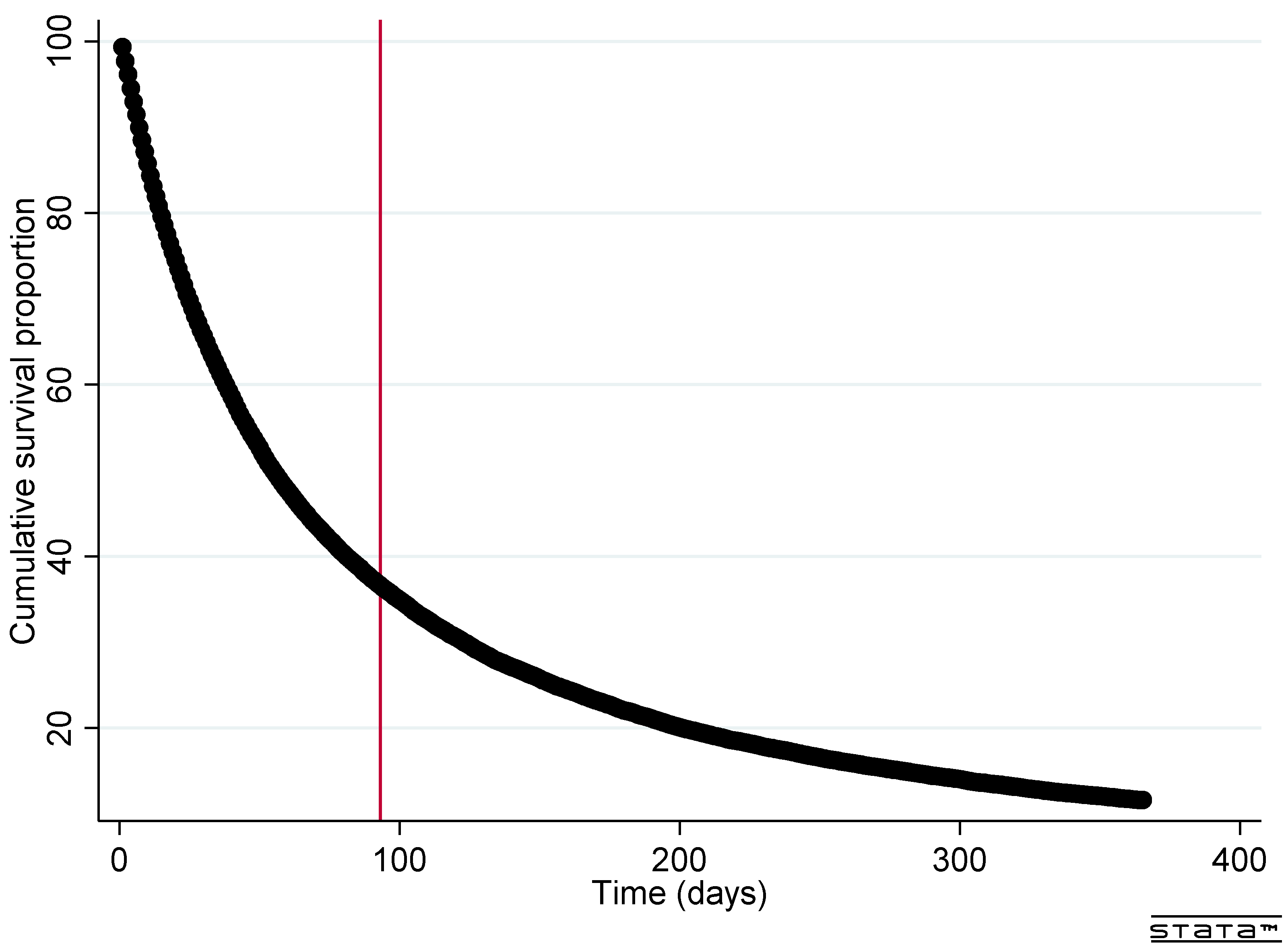

3.2. Time to End-of-Life

3.3. Geographical Variation

4. Discussion

4.1. Prior Studies

4.1.1. Time to End-of-Life

4.1.2. Geographical Variation

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Clinical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. WHO Definition of Palliative Care. Available online: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ (accessed on 7 January 2021).

- WHO. WHO Global Atlas of Palliative Care. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/integrated-health-services-(ihs)/csy/palliative-care/whpca_global_atlas_p5_digital_final.pdf?sfvrsn=1b54423a_3 (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Timm, H.U.; Mikkelsen, T.B.; Jarlbæk, L. Specialized palliative care in Danmark lacks capacity and accessibility [Specialiseret palliativ indsats i Danmark mangler kapacitet og tilgængelighed]. Ugeskr. Laeger 2017, 179, 1834–1837. [Google Scholar]

- Skov Benthien, K.; Adsersen, M.; Petersen, M.A.; Vadstrup, E.S.; Sjøgren, P.; Groenvold, M. Is specialized palliative cancer care associated with use of antineoplastic treatment at the end of life? A population-based cohort study. Palliat Med. 2018, 32, 1509–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etkind, S.N.; Bone, A.E.; Gomes, B.; Lovell, N.; Evans, C.J.; Higginson, I.J.; Murtagh, F.E.M. How many people will need palliative care in 2040? Past trends, future projections and implications for services. BMC Med. 2017, 15, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferrell, B.R.; Temel, J.S.; Temin, S.; Alesi, E.R.; Balboni, T.A.; Basch, E.M.; Firn, J.I.; Paice, J.A.; Peppercorn, J.M.; Phillips, T.; et al. Integration of Palliative Care into Standard Oncology Care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clegg, A.; Young, J.; Iliffe, S.; Rikkert, M.O.; Rockwood, K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 2013, 381, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fitzmaurice, C.; Abate, D.; Abbasi, N.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdel-Rahman, O.; Abdelalim, A.; Abdoli, A.; Abdollahpour, I.; Abdulle, A.S.M.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived with Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life-Years for 29 Cancer Groups, 1990 to 2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 1749–1768. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zimmermann, C.; Swami, N.; Krzyzanowska, M.; Hannon, B.; Leighl, N.; Oza, A.; Moore, M.; Rydall, A.; Rodin, G.; Tannock, I.; et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014, 383, 1721–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.P.; Temel, J.S.; Balboni, T.; Glare, P. A review of the trials which examine early integration of outpatient and home palliative care for patients with serious illnesses. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2015, 4, 99–121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jordan, R.I.; Allsop, M.J.; ElMokhallalati, Y.; Jackson, C.E.; Edwards, H.L.; Chapman, E.J.; Deliens, L.; Bennett, M.I. Duration of palliative care before death in international routine practice: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temel, J.S.; Greer, J.A.; El-Jawahri, A.; Pirl, W.F.; Park, E.R.; Jackson, V.A.; Back, A.L.; Kamdar, M.; Jacobsen, J.; Chittenden, E.H.; et al. Effects of Early Integrated Palliative Care in Patients with Lung and GI Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 834–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, D.; Kim, S.H.; Roquemore, J.; Dev, R.; Chisholm, G.; Bruera, E. Impact of timing and setting of palliative care referral on quality of end-of-life care in cancer patients. Cancer 2014, 120, 1743–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddison, A.R.; Asada, Y.; Burge, F.; Johnston, G.M.; Urquhart, R. Inequalities in End-of-Life Care for Colorectal Cancer Patients in Nova Scotia, Canada. J. Palliat. Care 2012, 28, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beccaro, M.; The ISDOC Study Group; Costantini, M.; Merlo, D.F. Inequity in the provision of and access to palliative care for cancer patients. Results from the Italian survey of the dying of cancer (ISDOC). BMC Public Health 2007, 7, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lackan, N.A.; Ostir, G.V.; Freeman, J.L.; Mahnken, J.D.; Goodwin, J.S. Decreasing Variation in the Use of Hospice Among Older Adults with Breast, Colorectal, Lung, and Prostate Cancer. Med. Care 2004, 42, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allsop, M.J.; E Ziegler, L.; Mulvey, M.R.; Russell, S.; Taylor, R.; Bennett, M. Duration and determinants of hospice-based specialist palliative care: A national retrospective cohort study. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 1322–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hansen, M.B.; Grønvold, M. The Danish Palliative Care Database Annual Report 2019 [Dansk Palliative Database Årsrapport 2019]. Available online: http://www.dmcgpal.dk/files/dpd/aarsrapport/aarsrapport_dpd_2019.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2022).

- Hansen, M.B.; Grønvold, M. The Danish Palliative Care Database Annual Report 2020 [Dansk Palliativ Database Årsrapport 2020]. Available online: http://www.dmcgpal.dk/files/aarsrapport_dpd_2020_med_3_reglen23_6_21.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2022).

- Radbruch, L.; Andersohn, F.; Walker, J. Oversupply Curative—Undersupply Palliative? Analysis of Selected End-of-Life Treatments [Ûberversogung Lurativ—Unterversorgung Palliativ? Analyse Ausgewählter. Behandlungen am Lebensende]. 2015. Available online: https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/fileadmin/files/BSt/Publikationen/GrauePublikationen/Studie_VV__FCG_Ueber-Unterversorgung-palliativ.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2022).

- Lynge, E.; Sandegaard, J.L.; Rebolj, M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand. J. Public Health 2011, 39, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Schmidt, S.A.J.; Sandegaard, J.L.; Ehrenstein, V.; Pedersen, L.; Sørensen, H.T. The Danish National Patient Registry: A review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin. Epidemiol. 2015, 7, 449–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adsersen, M.; Thygesen, L.; Neergaard, M.A.; Jensen, A.B.; Sjøgren, P.; Damkier, A.; Grønvold, M. Admittance to specialized palliative care (SPC) of patients with an assessed need: A study from the Danish palliative care database (DPD). Acta Oncol. 2017, 56, 1210–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Groenvold, M.; Adsersen, M.; Hansen, M.B. Danish Palliative Care Database. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 8, 637–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aalen, O.O.; Cook, R.J.; Røysland, K. Does Cox analysis of a randomized survival study yield a causal treatment effect? Lifetime Data Anal. 2015, 21, 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andersen, P.K.; Perme, M.P. Pseudo-observations in survival analysis. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2009, 19, 71–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boltezar, L.; Novakovic, B.J.; Moltara, M.E. Trends in specialized palliative care referrals at an oncology center from 2007 to 2019. BMC Palliat. Care 2021, 20, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parajuli, J.; Hupcey, J.E. A Systematic Review on Barriers to Palliative Care in Oncology. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2021, 38, 1361–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, N.; Reid, F.; Harris, A.; Harries, P.; Stone, P. A Systematic Review of Predictions of Survival in Palliative Care: How Accurate Are Clinicians and Who Are the Experts? PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161407. [Google Scholar]

- Gramling, R.; Gajary-Coots, E.; Cimino, J.; Fiscella, K.; Epstein, R.; Ladwig, S.; Anderson, W.; Alexander, S.C.; Han, P.K.; Gramling, D.; et al. Palliative Care Clinician Overestimation of Survival in Advanced Cancer: Disparities and Association with End-of-Life Care. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2019, 57, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Paiva, C.E.; del Fabbro, E.G.; Steer, C.; Naberhuis, J.; van de Wetering, M.; Fernández-Ortega, P.; Morita, T.; Suh, S.Y.; Bruera, E.; et al. Prognostication in advanced cancer: Update and directions for future research. Support Care Cancer 2019, 27, 1973–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakitas, M.A.; Tosteson, T.D.; Li, Z.; Lyons, K.; Hull, J.G.; Li, Z.; Dionne-Odom, J.N.; Frost, J.; Dragnev, K.H.; Hegel, M.T.; et al. Early Versus Delayed Initiation of Concurrent Palliative Oncology Care: Patient Outcomes in the ENABLE III Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 1438–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burge, F.I.; Lawson, B.J.; Johnston, G.M.; Grunfeld, E. A Population-based Study of Age Inequalities in Access to Palliative Care among Cancer Patients. Med. Care 2008, 46, 1203–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cerni, J.; Rhee, J.; Hosseinzadeh, H. End-of-Life Cancer Care Resource Utilisation in Rural Versus Urban Settings: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| 27,724 (100) | 6676 (100) | 7051 (100) | 6944 (100) | 7053 (100) | |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 13,443 (48.5) | 3240 (48.5) | 3427 (48.6) | 3395 (48.9) | 3381 (47.9) |

| Male | 14,281 (51.5) | 3436 (51.5) | 3624 (51.4) | 3549 (51.1) | 3672 (52.1) |

| Age group | |||||

| 18–30 | 159 (0.6) | 36 (0.5) | 41 (0.6) | 35 (0.5) | 47 (0.7) |

| 31–65 | 9084 (32.8) | 2307 (34.6) | 2317 (32.9) | 2254 (32.5) | 2206 (31.3) |

| 65+ | 18,481 (66.7) | 4333 (64.9) | 4693 (66.6) | 4655 (67.0) | 4800 (68.1) |

| Referred with cancer diagnosis | |||||

| No | 1532 (5.5) | 218 (3.3) | 291 (4.1) | 411 (5.9) | 612 (8.7) |

| Yes | 26,192 (94.5) | 6458 (96.7) | 6760 (95.9) | 6533 (94.1) | 6441 (91.3) |

| Duration from referral to start | |||||

| 0–10 days | 18,507 (66.8) | 4649 (69.6) | 4862 (69.0) | 4573 (65.9) | 4423 (62.7) |

| ≥11 days | 9217 (33.2) | 2027 (30.4) | 2189 (31.0) | 2371 (34.1) | 2630 (37.3) |

| Time to end-of-life | |||||

| <3 months | 17,355 (62.6%) | 4199 (62.9%) | 4489 (63.7%) | 4317 (62.2%) | 4350 (61.7%) |

| 3–12 months | 7149 (25.8%) | 1720 (25.8%) | 1784 (25.3%) | 1799 (25.9%) | 1846 (26.2%) |

| 1+ year | 3220 (11.6%) | 757 (11.3%) | 778 (11.0%) | 828 (11.9%) | 857 (12.2%) |

| Median duration (IQR) | 55 (20–156) | 55 (20–155) | 54 (20–152) | 55 (20–158) | 57 (21–158) |

| % (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | E-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 36.7 (36.2–37.1) | n.a | n.a |

| Region | |||

| Capital Region of Denmark | 40.1 (39.0–41.3) | 1 | 1 |

| Region Zealand | 38.0 (36.8–39.2) | 0.95 (0.91–0.99) | 1.30 |

| Region of Southern Denmark | 37.2 (36.0–38.5) | 0.93 (0.89–0.97) | 1.37 |

| Central Denmark Region | 34.5 (33.3–35.7) | 0.86 (0.82–0.90) | 1.60 |

| North Denmark Region | 32.5 (30.9–34.0) | 0.81 (0.77–0.85) | 1.78 |

| Year | |||

| 2015 | 36.3 (35.0–37.6) | 1 | 1 |

| 2016 | 35.7 (34.5–37.0) | 0.98 (0.94–1.03) | 1.15 |

| 2017 | 37.0 (36.0–38.1) | 1.02 (0.97–1.07) | 1.16 |

| 2018 | 37.5 (36.3–38.6) | 1.03 (0.98–1.08) | 1.21 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jøhnk, C.; Laigaard, H.H.; Pedersen, A.K.; Bauer, E.H.; Brandt, F.; Bollig, G.; Wolff, D.L. Time to End-of-Life of Patients Starting Specialised Palliative Care in Denmark: A Descriptive Register-Based Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13017. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013017

Jøhnk C, Laigaard HH, Pedersen AK, Bauer EH, Brandt F, Bollig G, Wolff DL. Time to End-of-Life of Patients Starting Specialised Palliative Care in Denmark: A Descriptive Register-Based Cohort Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(20):13017. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013017

Chicago/Turabian StyleJøhnk, Camilla, Helene Holm Laigaard, Andreas Kristian Pedersen, Eithne Hayes Bauer, Frans Brandt, Georg Bollig, and Donna Lykke Wolff. 2022. "Time to End-of-Life of Patients Starting Specialised Palliative Care in Denmark: A Descriptive Register-Based Cohort Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 20: 13017. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013017