Maternal Mortality in Africa: Regional Trends (2000–2017)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

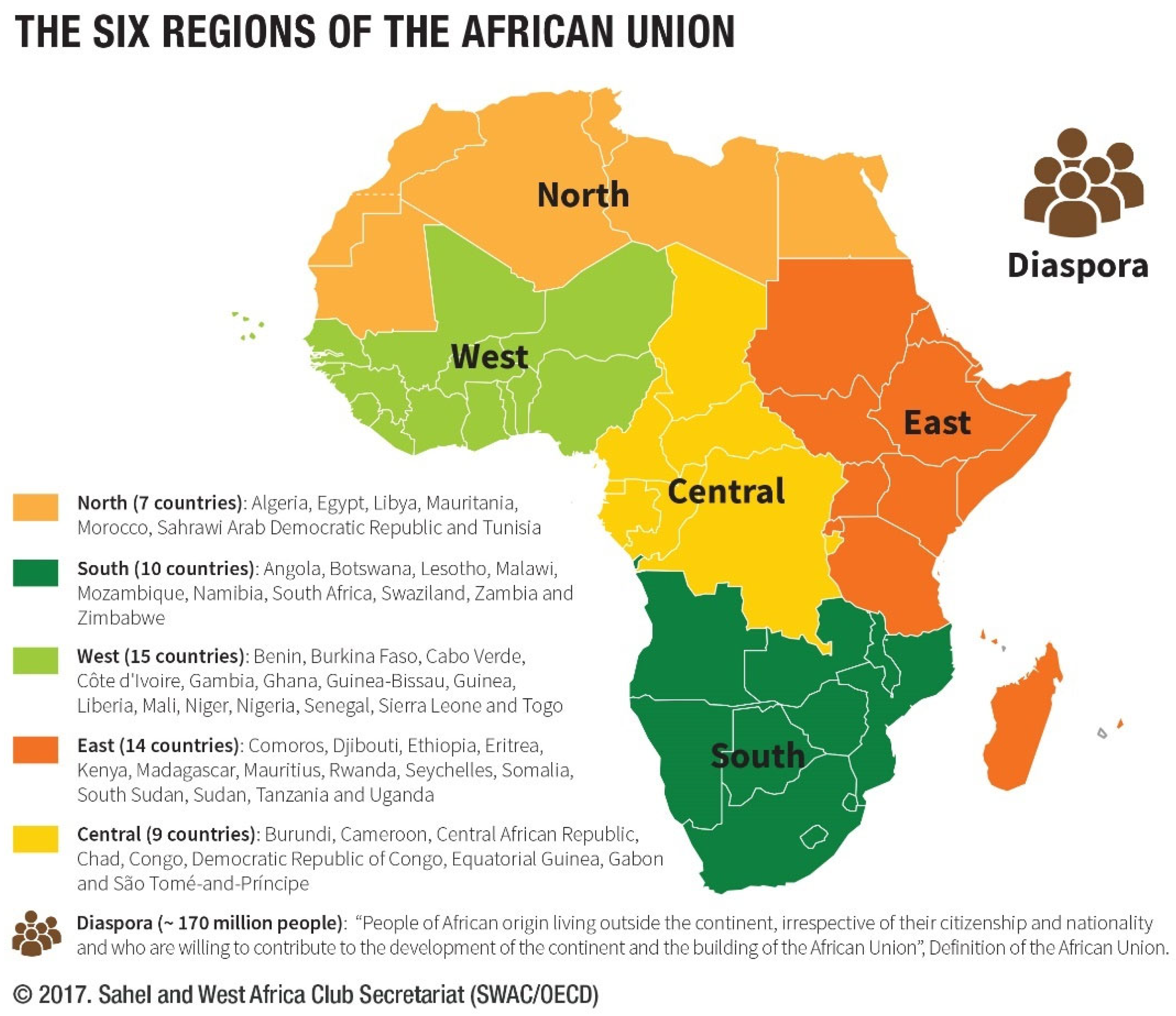

3.1. Region Classification

3.2. Data Sources

3.3. Joinpoint Regression

3.4. Study Variables

3.5. Autocorrelation Empirical Models

3.6. Comparison between Regions

3.7. Software

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of the African Continent

4.2. Analysis of African Regions

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. World Health Organization ICD-10: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Health Related Problems, 10th ed.; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- The Global Health Observatory (WHO). Maternal Deaths. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/indicator-metadata-registry/imr-details/4622 (accessed on 16 April 2022).

- WHO. A Regional Strategic Framework for Accelerating Universal Access to Sexual and Reproductive Health, WHO South-East Asia Region, 2020–2024.; World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia: New Delhi, India, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. World Health Statistics 2018: Monitoring Health for the SDGs.; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Ending Preventable Maternal Mortality (EPMM). A Renewed Focus for Improving Maternal and Newborn Health and Well-Being; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, M.C.; Foreman, K.J.; Naghavi, M.; Ahn, S.Y.; Wang, M.; Makela, S.M.; Lopez, A.D.; Lozano, R.; Murray, C.J. Maternal Mortality for 181 Countries, 1980–2008: A Systematic Analysis of Progress towards Millennium Development Goal 5. Lancet 2010, 375, 1609–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Maternal Mortality. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality (accessed on 6 April 2022).

- Jeong, W.; Jang, S.-I.; Park, E.-C.; Nam, J.Y. The Effect of Socioeconomic Status on All-Cause Maternal Mortality: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagher, R.K.; Linares, D.E. A Critical Review on the Complex Interplay between Social Determinants of Health and Maternal and Infant Mortality. Children 2022, 9, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haggaz, A.D.; Radi, E.A.; Adam, I. High Perinatal Mortality in Darfur, Sudan. J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal Med. 2008, 21, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urdal, H.; Che, C.P. War and Gender Inequalities in Health: The Impact of Armed Conflict on Fertility and Maternal Mortality. Int. Interact. 2013, 39, 489–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, C.A.; Linhart, C.L.; Beckley, W.; Pardosi, J.F. Maternal Mortality in Sierra Leone: From Civil War to Ebola and the Sustainable Development Goals. Int. J. Public Health 2018, 63, 431–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatusić, Z.; Kurjak, A.; Grgić, G.; Tulumović, A. The Influence of the War on Perinatal and Maternal Mortality in Bosnia and Herzegovina. J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal Med. 2005, 18, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, N.S. Unsafe Motherhood: Mayan Maternal Mortality and Subjectivity in Post-War Guatemala; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Murty, K.S.; McCamey, J.D. Maternal Health and Maternal Mortality in Post War Liberia: A Survey Analysis. In Applied Demography and Public Health; Hoque, N., McGehee, M.A., Bradshaw, B.S., Eds.; Springer Dordrecht: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 189–231. [Google Scholar]

- Yaya, S.; Uthman, O.A.; Bishwajit, G.; Ekholuenetale, M. Maternal Health Care Service Utilization in Post-War Liberia: Analysis of Nationally Representative Cross-Sectional Household Surveys. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Maternal Death Surveillance and Response: Technical Guidance Information for Action to Prevent Maternal Death; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, H.; Ameh, C.; Roos, N.; Mathai, M.; van den Broek, N. Implementing Maternal Death Surveillance and Response: A Review of Lessons from Country Case Studies. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tura, A.K.; Fage, S.G.; Ibrahim, A.M.; Mohamed, A.; Ahmed, R.; Gure, T.; Zwart, J.; van den Akker, T. Beyond No Blame: Practical Challenges of Conducting Maternal and Perinatal Death Reviews in Eastern Ethiopia. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2020, 8, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouanda, S.; Ouedraogo, O.M.A.; Tchonfiene, P.P.; Lhagadang, F.; Ouedraogo, L.; Conombo Kafando, G.S. Analysis of the Implementation of Maternal Death Surveillance and Response in Chad. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2022, 158, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compaoré, R.; Millogo, T.; Ouedraogo, A.M.; Tougri, H.; Ouedraogo, L.; Tall, F.; Kouanda, S. Maternal and Neonatal Death Surveillance and Response in Liberia: An Assessment of the Implementation Process in Five Counties. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2022, 158, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compaoré, R.; Kouanda, S.; Kuma-Aboagye, P.; Sagoe-Moses, I.; Brew, G.; Deganus, S.; Srofenyo, E.; Dansowaa Doe, R.; Nkurunziza, T.; Tall, F. Transitioning to the Maternal Death Surveillance and Response System from Maternal Death Review in Ghana: Challenges and Lessons Learned. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2022, 158, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musarandega, R.; Machekano, R.; Munjanja, S.P.; Pattinson, R. Methods Used to Measure Maternal Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa from 1980 to 2020: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022, 156, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippi, V.; Chou, D.; Barreix, M.; Say, L. A New Conceptual Framework for Maternal Morbidity. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018, 141, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, B.N.; Sohail, A. Ramification of Healthcare Expenditure on Morbidity Rates and Life Expectancy in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations Countries: A Dynamic Panel Threshold Analysis. Int. J. Health Plann. Manag. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz, N.; He, J.; Sarker, T.; Sui, H. Exploring the Role of Health Expenditure and Maternal Mortality in South Asian Countries: An Approach towards Shaping Better Health Policy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nketiah-Amponsah, E. The Impact of Health Expenditures on Health Outcomes in Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Dev. Soc. 2019, 35, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, V.N.R.; Okunade, A.A. The Core Determinants of Health Expenditure in the African Context: Some Econometric Evidence for Policy. Health Policy 2009, 91, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyu, L.D.; Kadas, A.S.; Mohammed, A.; Abdulllahi, H.M.; Farouk, Z.; Usman, F.; Attah, R.A.; Yusuf, M.; Magashi, M.K.; Miko, M. Impediments to Maternal Mortality Reduction in Africa: A Systemic and Socioeconomic Overview. J. Perinat. Med. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2017: Monitoring Health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Uppsala University Department of Peace and Conflict Research. Uppsala Conflict Data Program. Available online: https://ucdp.uu.se/ (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Themnér, L.; Wallensteen, P. Armed Conflicts, 1946–2011. J. Peace Res. 2012, 49, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Themnér, L.; Wallensteen, P. Armed Conflicts, 1946–2012. J. Peace Res. 2013, 50, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamkhezri, J.; Razzaghi, S.; Khezri, M.; Heshmati, A. Regional Effects of Maternal Mortality Determinants in Africa and the Middle East: How About Political Risks of Conflicts? Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Pregnancy-Related Deaths. Vital Signs 2019, 1–2. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/maternal-deaths/index.html (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Pradhan, T.K.; Qian, J.M.; Sutliff, V.E.; Mantey, S.A.; Jensen, R.T. Identification of CCK-A Receptors on Chief Cells with Use of a Novel, Highly Selective Ligand. Am. J. Physiol. 1995, 268 Pt 1, G605–G612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Say, L.; Chou, D.; Gemmill, A.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Moller, A.-B.; Daniels, J.; Gülmezoglu, A.M.; Temmerman, M.; Alkema, L. Global Causes of Maternal Death: A WHO Systematic Analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2014, 2, e323–e333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassebaum, N.J.; Bertozzi-Villa, A.; Coggeshall, M.S.; Shackelford, K.A.; Steiner, C.; Heuton, K.R.; Gonzalez-Medina, D.; Barber, R.; Huynh, C.; Dicker, D.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Levels and Causes of Maternal Mortality during 1990–2013: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014, 384, 980–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2015 Maternal Mortality Collaborators. Global, Regional, and National Levels of Maternal Mortality, 1990–2015: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016, 388, 1775–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, S.; Mahendra, S.; Bose, K.; Camacho, A.V.; Mathai, M.; Nove, A.; Santana, F.; Matthews, Z. The Causes of Maternal Mortality in Adolescents in Low and Middle Income Countries: A Systematic Review of the Literature. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musarandega, R.; Nyakura, M.; Machekano, R.; Pattinson, R.; Munjanja, S.P. Causes of Maternal Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review of Studies Published from 2015 to 2020. J. Glob. Health 2021, 11, 04048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taye Makuria, A.; Gebremichael, D.; Demoz, H.; Hadush, A.; Abdella, Y.; Berhane, Y.; Kamani, N. Obstetric Hemorrhage and Safe Blood for Transfusion in Ethiopia: The Challenges of Bridging the Gap. Transfusion 2017, 57, 2526–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diallo, A.; Michalek, I.M.; Bah, I.K.; Diallo, I.A.; Sy, T.; Roth-Kleiner, M.; Desseauve, D. Maternal Mortality Risk Indicators: Case-Control Study at a Referral Hospital in Guinea. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 251, 254–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, A.; Malqvist, M.; Pembe, A.B.; Massawe, S.; Hanson, C. Causes of Maternal Deaths and Delays in Care: Comparison between Routine Maternal Death Surveillance and Response System and an Obstetrician Expert Panel in Tanzania. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadush, A.; Dagnaw, F.; Getachew, T.; Bailey, P.E.; Lawley, R.; Ruano, A.L. Triangulating Data Sources for Further Learning from and about the MDSR in Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Review of Facility Based Maternal Death Data from EmONC Assessment and MDSR System. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes-Josiah, D.; Myntti, C.; Augustin, A. The “Three Delays” as a Framework for Examining Maternal Mortality in Haiti. Soc. Sci. Med. 1998, 46, 981–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiruneh, G.T.; Getu, Y.N.; Abdukie, M.A.; Eba, G.G.; Keyes, E.; Bailey, P.E. Distribution of Maternity Waiting Homes and Their Correlation with Perinatal Mortality and Direct Obstetric Complication Rates in Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkema, L.; Chou, D.; Hogan, D.; Zhang, S.; Moller, A.-B.; Gemmill, A.; Fat, D.M.; Boerma, T.; Temmerman, M.; Mathers, C.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Levels and Trends in Maternal Mortality between 1990 and 2015, with Scenario-Based Projections to 2030: A Systematic Analysis by the UN Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group. Lancet 2016, 387, 462–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croke, K.; Gage, A.; Fulcher, I.; Opondo, K.; Nzinga, J.; Tsofa, B.; Haneuse, S.; Kruk, M. Service Delivery Reform for Maternal and Newborn Health in Kakamega County, Kenya: Study Protocol for a Prospective Impact Evaluation and Implementation Science Study. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolossa, T.; Fetensa, G.; Zewde, E.A.; Besho, M.; Jidha, T.D. Magnitude of Postpartum Hemorrhage and Associated Factors among Women Who Gave Birth in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Reprod. Health 2022, 19, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lincetto, O.; Mothebesoane-Anoh, S.; Gomez, P.; Munjanja, S. Opportunities for Africa’s Newborns; WHO, Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- PMNCH. Opportunities for Africa’s Newborns; Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, I.; Walker, P.; Tagbor, H.; Bojang, K.; Coulibaly, S.O.; Kayentao, K.; Williams, J.; Oduro, A.; Milligan, P.; Chandramohan, D.; et al. Seasonal Dynamics of Malaria in Pregnancy in West Africa: Evidence for Carriage of Infections Acquired Before Pregnancy Until First Contact with Antenatal Care. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018, 98, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grange, J.; Adhikari, M.; Ahmed, Y.; Mwaba, P.; Dheda, K.; Hoelscher, M.; Zumla, A. Tuberculosis in Association with HIV/AIDS Emerges as a Major Nonobstetric Cause of Maternal Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2010, 108, 181–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- African Union. Report of the Meeting of Experts from Member States on the Definition of the African Diaspora; African Union: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- African Union. Protocol on the Amendments to the Constitutive Act of the African Union; African Union: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Maternal Mortality Data [Database]. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/resources/dataset/maternal-mortality-data/ (accessed on 21 July 2022).

- World Bank. Health Nutrition and Population Statistics: Population Estimates and Projections. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/population-estimates-and-projections# (accessed on 14 April 2022).

- Master Nation. Mother’s Mean Age at First Birth: Countries Compared. Available online: https://www.nationmaster.com/country-info/stats/People/Mother’s-mean-age-at-first-birth# (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- USAID. STATcompiler DHS Program. Available online: https://www.statcompiler.com/en/ (accessed on 21 September 2022).

- Durbin, J.; Watson, G.S. Testing for Serial Correlation in Least Squares Regression. II. Biometrika 1951, 38, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Durbin-Watson Test: Definition & Example—Statology. Available online: https://www.statology.org/durbin-watson-test/ (accessed on 14 April 2022).

- Test for Autocorrelation by Using the Durbin-Watson Statistic—Minitab. Available online: https://support.minitab.com/en-us/minitab/18/help-and-how-to/modeling-statistics/regression/supporting-topics/model-assumptions/test-for-autocorrelation-by-using-the-durbin-watson-statistic/ (accessed on 14 April 2022).

- Kim, H.-J.; Fay, M.P.; Yu, B.; Barrett, M.J.; Feuer, E.J. Comparability of Segmented Line Regression Models. Biometrics 2004, 60, 1005–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minitab 17 Statistical Software. Minitab, Inc.: State College, PA, USA, 2010.

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- R Studio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio; PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- RStudio for Windows. Boston 2022. Available online: https://www.rstudio.com/products/rstudio/download/ (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Statistical Research and Applications Branc. Joinpoint Regression Version; National Cancer Institute: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.J.; Fay, M.P.; Feuer, E.J.; Midthune, D.N. Permutation Tests for Joinpoint Regression with Applications to Cancer Rates. Stat. Med. 2000, 19, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Data Bank Africa Development Indicators. Available online: http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/africa-development-indicators (accessed on 28 July 2018).

- Shiferaw, K.; Mengistie, B.; Gobena, T.; Dheresa, M.; Seme, A. Neonatal Mortality Rate and Its Determinants: A Community-Based Panel Study in Ethiopia. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 875652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rispel, L.; Moorman, J. Health Legislation and Policy: Context, Process and Progress: Reflections on the Millennium Development Goals. S. Afr. Health Rev. 2010, 2010, 127–142. [Google Scholar]

- Mensah, J. The Global Financial Crisis and Access to Health Care in Africa. Afr. Today 2014, 60, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruckert, A.; Labonté, R. The Global Financial Crisis and Health Equity: Toward a Conceptual Framework. Crit. Public Health 2012, 22, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach-Kemon, K.; Chou, D.P.; Schneider, M.T.; Tardif, A.; Dieleman, J.L.; Brooks, B.P.C.; Hanlon, M.; Murray, C.J.L. The Global Financial Crisis Has Led To A Slowdown In Growth Of Funding To Improve Health In Many Developing Countries. Health Aff. 2012, 31, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutts, A.; Stuckler, D.; Batniji, R.; Ismail, S.; Maziak, W.; McKee, M. The Arab Spring and Health: Two Years On. Int. J. Health Serv. 2013, 43, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bou-Karroum, L.; Daou, K.N.; Nomier, M.; El Arnaout, N.; Fouad, F.M.; El-Jardali, F.; Akl, E.A. Health Care Workers in the Setting of the “Arab Spring”: A Scoping Review for the Lancet-AUB Commission on Syria. J. Glob. Health 2019, 9, 010402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhouma, M. The Arab Spring in Tunisia: Urgent Plea for a Public Health System (r)Evolution. World Neurosurg. 2013, 80, 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirkin, B. Arab Spring: Demographics in a Region in Transition; United Nations Development Programme, Regional Bureau for Arab States: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Obasanjo, I. Social Conflict, Civil Society, and Maternal Mortality in African Countries. Leadership 2018, 14, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karshenas, M.; Moghadam, V.M.; Alami, R. Social Policy after the Arab Spring: States and Social Rights in the MENA Region. World Dev. 2014, 64, 726–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, S.S.; Alameddine, M.S.; Natafgi, N.M.; Mataria, A.; Sabri, B.; Nasher, J.; Zeiton, M.; Ahmad, S.; Siddiqi, S. The Path towards Universal Health Coverage in the Arab Uprising Countries Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Yemen. Lancet 2014, 383, 368–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. GDP per Capita (Current US$)—South Africa [Data Base]. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?contextual=region&locations=ZA&view=chart (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- World Bank. GDP (Current US$)—Mozambique [Database]. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=MZ&view=chart (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- World Bank. GDP (Current US$)—Angola [Data Base]. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=AO&view=chart (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- World Bank. GDP (Current US$)—Zimbabwe [Database]. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=ZW&view=chart (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- United Nations. Standard Country or Area Codes for Statistical Use (M49). Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/ (accessed on 6 April 2022).

- Department of Economical and Social Affairs. Statistics Division. Standard Country or Area Codes for Statistical Use; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sahel and West Africa Club. The Six Regions of the African Union. Maps Facts 2017, 48, 1–2. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/swac/maps/48-six-regions-African-Union.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Ayele, A.A.; Tefera, Y.G.; East, L. Ethiopia’s Commitment towards Achieving Sustainable Development Goal on Reduction of Maternal Mortality: There Is a Long Way to Go. Womens Health 2021, 17, 17455065211067072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. Report on the Status of Civil Registration and Vital Statistics in Africa: Outcome of the Africa Programme on Accelerated Improvement of Civil Registration and Vital Statistics Systems Monitoring Framework; UN. ECA: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sankoh, O.; Dickson, K.E.; Faniran, S.; Lahai, J.I.; Forna, F.; Liyosi, E.; Kamara, M.K.; Jabbi, S.-M.B.-B.; Johnny, A.B.; Conteh-Khali, N.; et al. Births and Deaths Must Be Registered in Africa. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e33–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouchadi, S.; Zhang, W.-H.; De Brouwere, V. Underreporting of Deaths in the Maternal Deaths Surveillance System in One Region of Morocco. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0188070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helleringer, S.; Duthé, G.; Kanté, A.M.; Andro, A.; Sokhna, C.; Trape, J.-F.; Pison, G. Misclassification of Pregnancy-Related Deaths in Adult Mortality Surveys: Case Study in Senegal. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2013, 18, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenneker, M.; Ramnarain, H.; Sebitloane, H. A Clinical Conundrum: Review of Anticoagulation in Pregnant Women with Mechanical Prosthetic Heart Valves. Cardiovasc. J. Afr. 2022, 33, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyu, L.D.; Kadas, A.S.; Abdulsalam, M.; Abdulllahi, H.M.; Farouk, Z.; Usman, F.; Attah, R.A.; Yusuf, M.; Magashi, M.K.; Miko, M. Eclampsia a Preventable Tragedy: An African Overview. J. Perinat. Med. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndiaye, K.; Portillo, E.; Ouedraogo, D.; Mobley, A.; Babalola, S. High-Risk Advanced Maternal Age and High Parity Pregnancy: Tackling a Neglected Need Through Formative Research and Action. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2018, 6, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ataguba, J.E.-O. A Reassessment of Global Antenatal Care Coverage for Improving Maternal Health Using Sub-Saharan Africa as a Case Study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shireen, A.; Horton, L.; Bornstein, M.; Pullum, T. Levels and Trends of Maternal and Child Health Indicators in 11 Middle East and North African Countries. DHS Comparative Report No. 46; ICF: Rockville, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- National Department of Health—NDoH; Statistics South Africa—Stats SA; South African Medical Research Council—SAMRC; ICF. South Africa Demographic and Health Survey 2016; NDoH: Pretoria, South Africa; Stats SA: Pretoria, South Africa; SAMRC: Cape Town, South Africa; ICF: Rockville, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Delivery Care. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/topic/maternal-health/delivery-care/ (accessed on 24 September 2022).

- UNICEF. Antenatal Care. July 2022. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/topic/maternal-health/antenatal-care/ (accessed on 24 September 2022).

- Okedo-Alex, I.N.; Akamike, I.C.; Ezeanosike, O.B.; Uneke, C.J. Determinants of Antenatal Care Utilisation in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e031890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chol, C.; Negin, J.; Garcia-Basteiro, A.; Gebrehiwot, T.G.; Debru, B.; Chimpolo, M.; Agho, K.; Cumming, R.G.; Abimbola, S. Health System Reforms in Five Sub-Saharan African Countries That Experienced Major Armed Conflicts (Wars) during 1990–2015: A Literature Review. Glob. Health Action 2018, 11, 1517931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Cantero, M.T.; Guijarro-Garvi, M.; Bean, D.R.; Martínez-Riera, J.R.; Fernández-Sáez, J. Governance Commitment to Reduce Maternal Mortality. A Political Determinant beyond the Wealth of the Countries. Health Place 2019, 57, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukenya, B.; Golooba-Mutebi, F. What Explains Sub-National Variation in Maternal Mortality Rates within Developing Countries? A Political Economy Explanation. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 256, 113066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njah, M.; Mahjoub, M.; Atif, M.-L.; Belouali, R. Maternal Mortality in Maghreb: Problems and Challenges of Public Health. Tunis. Med. 2018, 96, 620–627. [Google Scholar]

- Dahab, R.; Sakellariou, D. Barriers to Accessing Maternal Care in Low Income Countries in Africa: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchemi, O.M.; Gichogo, A.W.; Mungai, J.G.; Roka, Z.G. Trends in Health Facility Based Maternal Mortality in Central Region, Kenya: 2008–2012. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2016, 23, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camara, B.S.; Delamou, A.; Grovogui, F.M.; de Kok, B.C.; Benova, L.; El Ayadi, A.M.; Gerrets, R.; Grietens, K.P.; Delvaux, T. Interventions to Increase Facility Births and Provision of Postpartum Care in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Scoping Review. Reprod. Health 2021, 18, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfay, N.; Tariku, R.; Zenebe, A.; Mohammed, F.; Woldeyohannes, F. Area of Focus to Handle Delays Related to Maternal Death in Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Combs Thorsen, V.; Sundby, J.; Malata, A. Piecing Together the Maternal Death Puzzle through Narratives: The Three Delays Model Revisited. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e52090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmonds, A.; Brazier, E.; Musick, B.S.; Yotebieng, M.; Humphrey, J.; Abuogi, L.L.; Adedimeji, A.; Keiser, O.; Msukwa, M.; Carlucci, J.G.; et al. Clinical and Programmatic Outcomes of HIV-Exposed Infants Enrolled in Care at Geographically Diverse Clinics, 1997–2021: A Cohort Study. PLoS Med. 2022, 19, e1004089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS). Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2016; UBOS: Kampala, Uganda, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Comfort, A.B.; El Ayadi, A.M.; Camlin, C.S.; Tsai, A.C.; Nalubwama, H.; Byamugisha, J.; Walker, D.M.; Moody, J.; Roberts, T.; Senoga, U.; et al. The Role of Informational Support from Women’s Social Networks on Antenatal Care Initiation: Qualitative Evidence from Pregnant Women in Uganda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacoella, F.; Gassmann, F.; Tirivayi, N. Which Communication Technology Is Effective for Promoting Reproductive Health? Television, Radio, and Mobile Phones in Sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0272501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawuki, J.; Gatasi, G.; Sserwanja, Q. Women Empowerment and Health Insurance Utilisation in Rwanda: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Survey. BMC Womens Health 2022, 22, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossman, E.; Johansen, M.A.; Zanaboni, P. MHealth Interventions to Reduce Maternal and Child Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa and Southern Asia: A Systematic Literature Review. Front. Glob. Women’s Health 2022, 3, 942146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattinson, R.; Moodley, J.F.S. Improvements in Maternal Mortality in South Africa. S. Afr. Med. J. 2018, 108, S4–S8. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, P.E.; Andualem, W.; Brun, M.; Freedman, L.; Gbangbade, S.; Kante, M.; Keyes, E.; Libamba, E.; Moran, A.C.; Mouniri, H.; et al. Institutional Maternal and Perinatal Deaths: A Review of 40 Low and Middle Income Countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambounda, N.L.; Woromogo, S.H.; Yagata-Moussa, F.-E.; Ossouka, L.A.O.; Tekem, V.N.S.; Ango, E.O.; Kouanang, A.J. Primary Postpartum Haemorrhage at the Libreville University Hospital Centre: Epidemiological Profile of Women. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngonzi, J.; Tornes, Y.F.; Mukasa, P.K.; Salongo, W.; Kabakyenga, J.; Sezalio, M.; Wouters, K.; Jacqueym, Y.; Van Geertruyden, J.-P. Puerperal Sepsis, the Leading Cause of Maternal Deaths at a Tertiary University Teaching Hospital in Uganda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngwenya, S. Factors Associated with Maternal Mortality from Sepsis in a Low-Resource Setting: A Five-Year Review at Mpilo Central Hospital, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. Trop. Doct. 2020, 50, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenstra, E.D.; Herklots, T.; Said Mbarouk, K.; Meguid, T.; Franx, A.; Jacod, B. Too Busy to Care? Analysing the Impact of System-Related Factors on Maternal Mortality in Zanzibar’s Referral Hospital. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunguya, B.F.; Ge, Y.; Mlunde, L.; Mpembeni, R.; Leyna, G.; Huang, J. High Burden of Anemia among Pregnant Women in Tanzania: A Call to Address Its Determinants. Nutr. J. 2021, 20, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeboye, T.E.; Bodunde, I.O.; Okekunle, A.P. Dietary Iron Intakes and Odds of Iron Deficiency Anaemia among Pregnant Women in Ifako-Ijaiye, Lagos, Nigeria: A Cross-Sectional Study. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2022, 42, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsamy, V.; Bagwandeen, C.; Moodley, J. The Prevalence, Risk Factors and Outcomes of Anaemia in South African Pregnant Women: A Protocol for a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Syst. Rev. 2020, 9, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodley, J.; Pattinson, R.; Baxter, C.; Sibeko, S.; Abdool Karim, Q. Strengthening HIV Services for Pregnant Women: An Opportunity to Reduce Maternal Mortality Rates in Southern Africa/Sub-Saharan Africa. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2011, 118, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godefay, H.; Byass, P.; Graham, W.J.; Kinsman, J.; Mulugeta, A. Risk Factors for Maternal Mortality in Rural Tigray, Northern Ethiopia: A Case-Control Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Periods | Years | APC (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Period | 2000–2017 | −3.0 (−3.3; −2.59) | <0.001 |

| Period 1 | 2000–2003 | −2.4 (−2.6; −2.1) | <0.001 |

| Period 2 | 2003–2008 | −3.9 (−4.1; −4.7) | <0.001 |

| Period 3 | 2008–2015 | −2.7 (−2.6; −2.8) | <0.001 |

| Period 4 | 2015–2017 | −1.3 (−1.8; −0.8) | 0.001 |

| Periods | Years | APC (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| North | |||

| Total Period | 2000–2017 | −2.8 (−3.5; −2.2) | <0.001 |

| Period 1 | 2000–2007 | −4.5 (−4.7; −4.7) | <0.001 |

| Period 2 | 2007–2013 | −2.0 (−2.3; −1.7) | <0.001 |

| Period 3 | 2013–2017 | −1.2 (−1.6; −0.7) | <0.001 |

| East | |||

| Total Period | 2000–2017 | −4.3 (−4.5; −4.1) | <0.001 |

| Period 1 | 2000–2004 | −3.1 (−3.3; −3.0) | <0.001 |

| Period 2 | 2004–2009 | −5.0 (−5.2; −4.9) | <0.001 |

| Period 3 | 2009–2015 | −4.5 (−4.6; −4.4) | <0.001 |

| Period 4 | 2015–2017 | −0.2 (−0.3; 0.8) | 0.370 |

| Central | |||

| Total Period | 2000–2017 | −2.7 (−2.8; −2.5) | <0.001 |

| Period 1 | 2000–2002 | −2.0 (−2.7; −1.2) | <0.001 |

| Period 2 | 2002–2006 | −3.9 (−4.2; −3.7) | <0.001 |

| Period 3 | 2006–2011 | −2.4 (−2.6; −2.4) | <0.001 |

| Period 4 | 2011–2017 | −2.0 (−2.0; −1.9) | <0.001 |

| South | |||

| Total Period | 2000–2015 | −4.8 (−5.0; −4.5) | <0.001 |

| Period 1 | 2000–2004 | −3.0 (−3.1.; −2.8) | <0.001 |

| Period 2 | 2004–2007 | −4.7 (−5.1; −4.3) | <0.001 |

| Period 3 | 2007–2013 | −6.0 (−6.1; −5.9) | <0.001 |

| Period 4 | 2013–2017 | −3.1 (−3.2; −3.0) | <0.001 |

| West | |||

| Total Period | 2000–2015 | −2.0 (−2.1; −1.8) | <0.001 |

| Period 1 | 2000–2003 | −1.5 (−1.8.; −1.3) | <0.001 |

| Period 2 | 2003–2007 | −3.5 (−3.7; −3.2) | <0.001 |

| Period 3 | 2007–2014 | −1.2 (−1.3; −1.2) | <0.001 |

| Period 4 | 2014–2017 | −1.9 (−2.1; −1.6) | <0.001 |

| Country | MMR | Country | MMR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colombia | 83 | Austria | 5 |

| Mexico | 33 | Belgium | 5 |

| Costa Rica | 27 | Ireland | 5 |

| Latvia | 19 | Japan | 5 |

| United States | 19 | Luxembourg | 5 |

| Turkey | 17 | Netherlands | 5 |

| Chile | 13 | Slovakia | 5 |

| Hungary | 12 | Switzerland | 5 |

| Republic of Korea | 11 | Denmark | 4 |

| Canada | 10 | Iceland | 4 |

| Estonia | 9 | Spain | 4 |

| New Zealand | 9 | Sweden | 4 |

| France | 8 | Czechia | 3 |

| Lithuania | 8 | Finland | 3 |

| Portugal | 8 | Greece | 3 |

| Germany | 7 | Israel | 3 |

| Slovenia | 7 | Italy | 2 |

| United Kingdom | 7 | Norway | 2 |

| Australia | 6 | Poland | 2 |

| Region | Mother’s Age at First Birth | 4+ Prenatal Care Visits | Health Facility Births |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central | 19.9 | 50.8% | 71.6% |

| Eastern | 19.7 | 55.5% | 51% |

| Northern | 23.5 | 72.3% | 84.0% |

| Southern | 20.6 | 60.1% | 76.7% |

| Western | 19.0 | 55.5% | 51.4% |

| Total Africa | 20.1 | 58.4% | 64.5% |

| Indicator | Central | East | South | West |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accessibility † | 84.9% | 91.7% | 80.2% | 97.9% |

| Sustainability follow-up in pregnancy ‡ | 82.5% | 89.5 | 71.9% | 86.6% |

| Sustainability follow-up in puerperium ¥ | 50.9% | 58.6% | 65.2% | 17.1% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Onambele, L.; Ortega-Leon, W.; Guillen-Aguinaga, S.; Forjaz, M.J.; Yoseph, A.; Guillen-Aguinaga, L.; Alas-Brun, R.; Arnedo-Pena, A.; Aguinaga-Ontoso, I.; Guillen-Grima, F. Maternal Mortality in Africa: Regional Trends (2000–2017). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13146. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013146

Onambele L, Ortega-Leon W, Guillen-Aguinaga S, Forjaz MJ, Yoseph A, Guillen-Aguinaga L, Alas-Brun R, Arnedo-Pena A, Aguinaga-Ontoso I, Guillen-Grima F. Maternal Mortality in Africa: Regional Trends (2000–2017). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(20):13146. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013146

Chicago/Turabian StyleOnambele, Luc, Wilfrido Ortega-Leon, Sara Guillen-Aguinaga, Maria João Forjaz, Amanuel Yoseph, Laura Guillen-Aguinaga, Rosa Alas-Brun, Alberto Arnedo-Pena, Ines Aguinaga-Ontoso, and Francisco Guillen-Grima. 2022. "Maternal Mortality in Africa: Regional Trends (2000–2017)" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 20: 13146. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013146

APA StyleOnambele, L., Ortega-Leon, W., Guillen-Aguinaga, S., Forjaz, M. J., Yoseph, A., Guillen-Aguinaga, L., Alas-Brun, R., Arnedo-Pena, A., Aguinaga-Ontoso, I., & Guillen-Grima, F. (2022). Maternal Mortality in Africa: Regional Trends (2000–2017). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13146. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013146

_MD__MPH_PhD.png)