Anorexic Readiness Syndrome in Elite Female Acrobatic Gymnasts—International Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Study Procedures

2.2. Surveys—The Personal Questionnaire and the Eating Attitudes Questionnaire (SGA-20)

2.3. Anthropometric Measurements

2.4. Statistical Analysis

- x2 is the Pearson chi-square statistic from the test,

- N is the sample size involved in the test,

- k is the smaller number of rows or column in contingency table.

3. Results

3.1. Classification of ARS Expression Levels

3.2. Analysis of the Responses Confirming the Risky Behavior in Relation to the ARS Levels

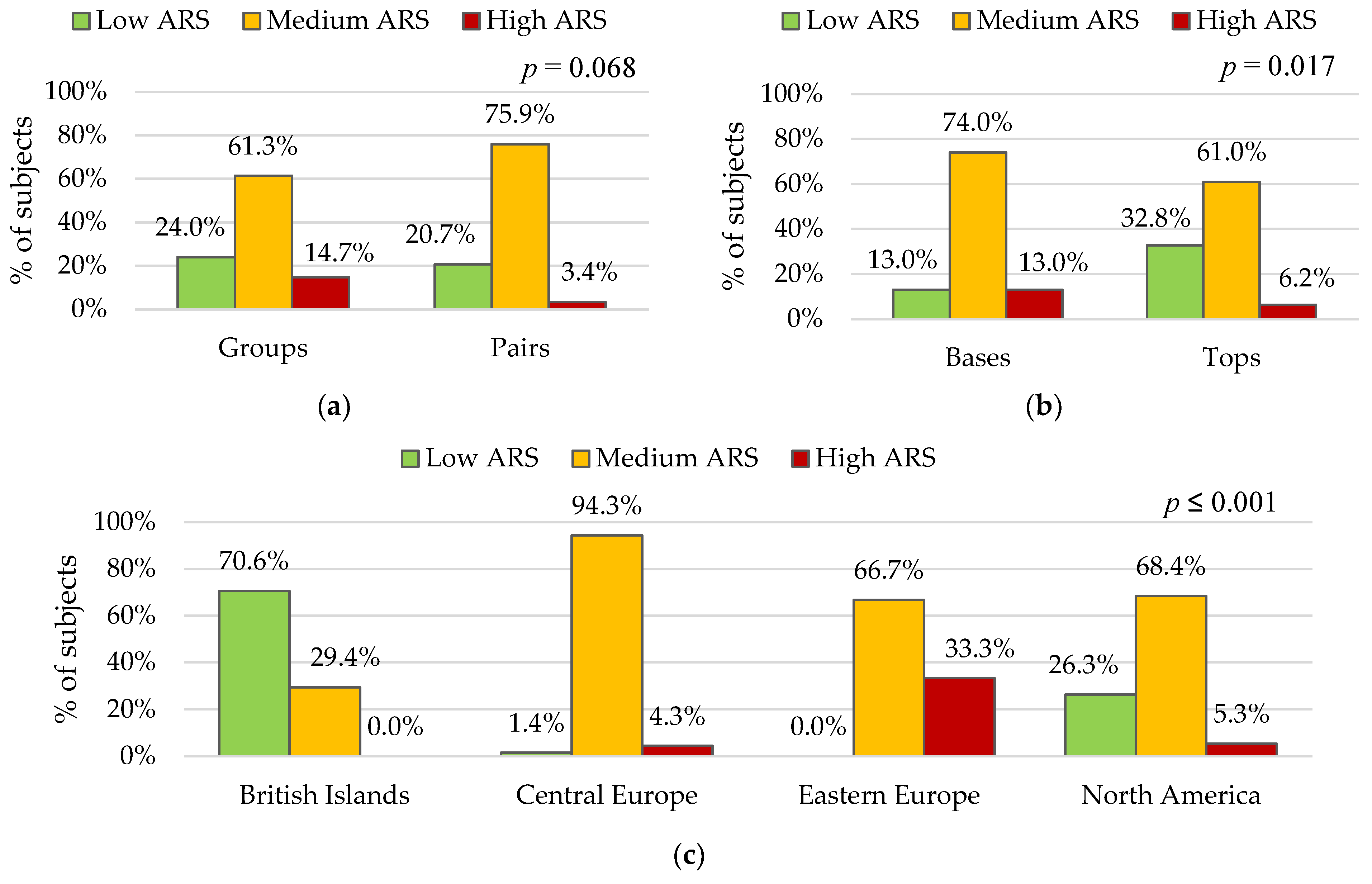

3.3. Relationships between ARS Levels and Sport-Related Factors

3.4. Relationships between the ARS Level and Non-Sport Factors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tomporowski, P.D.; Davis, C.L.; Miller, P.H.; Naglieri, J.A. Exercise and Children’s Intelligence, Cognition, and Academic Achievement. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 20, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagrove, R.; Bruinvels, G.; Read, P. Early Sport Specialization and Intensive Training in Adolescent Female Athletes: Risks and Recommendations. Strength Cond. J. 2017, 39, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mosher, A.; Till, K.; Fraser-Thomas, J.; Baker, J. Revisiting Early Sport Specialization: What’s the Problem? Sports Health 2022, 14, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moeskops, S.; Oliver, J.L.; Read, P.J.; Cronin, J.B.; Myer, G.D.; Lloyd, R.S. The Physiological Demands of Youth Artistic Gymnastics: Applications to Strength and Conditioning. Strength Cond. J. 2019, 41, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeskops, S.; Oliver, J.L.; Read, P.J.; Cronin, J.B.; Myer, G.D.; Lloyd, R.S. Practical Strategies for Integrating Strength and Conditioning into Early Specialization Sports. Strength Cond. J. 2022, 44, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sands, W.A.; McNeal, J.R.; Penitente, G.; Murray, S.R.; Nassar, L.; Jemni, M.; Mizuguchi, S.; Stone, M.H. Stretching the Spines of Gymnasts: A Review. Sport. Med. 2016, 46, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.; Barela, J.A.; Viana, A.R.; Barela, A.M.F. Influence of Gymnastics Training on the Development of Postural Control. Neurosci. Lett. 2011, 492, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kontele, I.; Vassilakou, T.; Donti, O. Weight Pressures and Eating Disorder Symptoms among Adolescent Female Gymnasts of Different Performance Levels in Greece. Children 2022, 9, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tournis, S.; Michopoulou, E.; Fatouros, I.G.; Paspati, I.; Michalopoulou, M.; Raptou, P.; Leontsini, D.; Avloniti, A.; Krekoukia, M.; Zouvelou, V.; et al. Effect of Rhythmic Gymnastics on Volumetric Bone Mineral Density and Bone Geometry in Premenarcheal Female Athletes and Controls. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 95, 2755–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Exupério, I.N.; Agostinete, R.R.; Werneck, A.O.; Maillane-Vanegas, S.; Luiz-de-Marco, R.; Mesquita, E.D.L.; Kemper, H.C.G.; Fernandes, R.A. Impact of Artistic Gymnastics on Bone Formation Marker, Density and Geometry in Female Adolescents: ABCD-Growth Study. J. Bone Metab. 2019, 26, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachner-Melman, R.; Zohar, A.H.; Ebstein, R.P.; Elizur, Y.; Constantini, N. How Anorexic-like Are the Symptom and Personality Profiles of Aesthetic Athletes? Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2006, 38, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibley, B.A.; Etnier, J.L. The Relationship between Physical Activity and Cognition in Children: A Meta-Analysis. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2003, 15, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sadowski, J.; Mastalerz, A.; Niznikowski, T. Benefits of Bandwidth Feedback in Learning a Complex Gymnastic Skill. J. Hum. Kinet. 2013, 37, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinsen, M.; Bahr, R.; Børresen, R.; Holme, I.; Pensgaard, A.M.; Sundgot-Borgen, J. Preventing Eating Disorders among Young Elite Athletes: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2014, 46, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordin, S.; Harris, G.; Cumming, J. Disturbed Eating in Young, Competitive Gymnasts: Differences between Three Gymnastics Disciplines. Eur. J. Sport. Sci. 2003, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, G.; Berman, E.; Souza, M.J.D. Disordered Eating in Women’s Gymnastics: Perspectives of Athletes, Coaches, Parents, and Judges. J. Appl. Sport. Psychol. 2006, 18, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.-R.G.; Silva, H.-H.; Paiva, T. Sleep Duration, Body Composition, Dietary Profile and Eating Behaviours among Children and Adolescents: A Comparison between Portuguese Acrobatic Gymnasts. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2018, 177, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernetta Santana, M.; Montosa, I.; Peláez-Barrios, E. Estima Corporal En Gimnastas Adolescentes de Dos Disciplinas Coreográficas: Gimnasia Rítmica y Gimnasia Acrobática. Psychol. Soc. Educ. 2018, 10, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kontele, I.; Vassilakou, T. Nutritional Risks among Adolescent Athletes with Disordered Eating. Children 2021, 8, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donti, O.; Donti, A.; Gaspari, V.; Pleksida, P.; Psychountaki, M. Are They Too Perfect to Eat Healthy? Association between Eating Disorder Symptoms and Perfectionism in Adolescent Rhythmic Gymnasts. Eat. Behav. 2021, 41, 101514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Calitri, R.; Bloodworth, A.; McNamee, M. Understanding Eating Disorders in Elite Gymnastics. Clin. Sport. Med. 2016, 35, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, C.L.; Hainline, B.; Aron, C.M.; Baron, D.; Baum, A.L.; Bindra, A.; Budgett, R.; Campriani, N.; Castaldelli-Maia, J.M.; Currie, A.; et al. Mental Health in Elite Athletes: International Olympic Committee Consensus Statement. Br. J. Sport. Med. 2019, 53, 667–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wells, K.R.; Jeacocke, N.A.; Appaneal, R.; Smith, H.D.; Vlahovich, N.; Burke, L.M.; Hughes, D. The Australian Institute of Sport (AIS) and National Eating Disorders Collaboration (NEDC) Position Statement on Disordered Eating in High Performance Sport. Br. J. Sport. Med. 2020, 54, 1247–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortes, L.D.S.; Kakeshita, I.S.; Almeida, S.S.; Gomes, A.R.; Ferreira, M.E.C. Eating Behaviours in Youths: A Comparison between Female and Male Athletes and Non-Athletes. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sport. 2014, 24, e62–e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Torstveit, M.K. Prevalence of Eating Disorders in Elite Athletes Is Higher than in the General Population. Clin. J. Sport. Med. 2004, 14, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Currie, A. Sport and Eating Disorders—Understanding and Managing the Risks. Asian J. Sport. Med. 2010, 1, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Torstveit, M.K. Aspects of Disordered Eating Continuum in Elite High-Intensity Sports. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2010, 20 (Suppl. S2), 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krentz, E.M.; Warschburger, P. Sports-Related Correlates of Disordered Eating in Aesthetic Sports. Psychol. Sport. Exerc. 2011, 12, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, R.; Alarcão, M.; Narciso, I. Aesthetic Sports as High-Risk Contexts for Eating Disorders--Young Elite Dancers and Gymnasts Perspectives. Span. J. Psychol. 2012, 15, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gramaglia, C.; Gambaro, E.; Delicato, C.; Marchetti, M.; Sarchiapone, M.; Ferrante, D.; Roncero, M.; Perpiñá, C.; Brytek-Matera, A.; Wojtyna, E.; et al. Orthorexia nervosa, eating patterns and personality traits: A cross-cultural comparison of Italian, Polish and Spanish university students. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Bloodworth, A.; McNamee, M.; Hewitt, J. Investigating Eating Disorders in Elite Gymnasts: Conceptual, Ethical and Methodological Issues. Eur. J. Sport. Sci. 2014, 14, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giel, K.E.; Hermann-Werner, A.; Mayer, J.; Diehl, K.; Schneider, S.; Thiel, A.; Zipfel, S.; GOAL study group. Eating Disorder Pathology in Elite Adolescent Athletes. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2016, 49, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonkiewicz, M.; Wawrzyniak, A. The Relationship between Rigorous Perception of One’s Own Body and Self, Unhealthy Eating Behavior and a High Risk of Anorexic Readiness: A Predictor of Eating Disorders in the Group of Female Ballet Dancers and Artistic Gymnasts at the Beginning of Their Career. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, N.; Heinen, T.; Elbe, A.-M. Factors Associated with Disordered Eating and Eating Disorder Symptoms in Adolescent Elite Athletes. Sport. Psychiatry 2022, 1, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Durme, K.; Goossens, L.; Braet, C. Adolescent Aesthetic Athletes: A Group at Risk for Eating Pathology? Eat. Behav. 2012, 13, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rauh, M.J.; Nichols, J.F.; Barrack, M.T. Relationships among Injury and Disordered Eating, Menstrual Dysfunction, and Low Bone Mineral Density in High School Athletes: A Prospective Study. J. Athl. Train. 2010, 45, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kontele, I.; Grammatikopoulou, M.G.; Vassilakou, T. Level of Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and Weight Status among Adolescent Female Gymnasts: A Cross-Sectional Study. Children 2021, 8, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziółlkowska, B. Uwarunkowania Ekspresji Syndromu Gotowości Anorektycznej [In Polish: Determinants of Anorexia Readiness Syndrom (ARS) Expression]. Sborník Pr. Filoz Fak Brněn. Univ. Ann. Psychol. 2000, 48, 35–55. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, K.A.; Dewoolkar, A.V.; Baker, N.; Dodich, C. The Female Athlete Triad: Special Considerations for Adolescent Female Athletes. Transl. Pediatr. 2017, 6, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sidiropoulos, M. Anorexia Nervosa: The Physiological Consequences of Starvation and the Need for Primary Prevention Efforts. McGill J. Med. MJM 2007, 10, 20–25. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2323541/ (accessed on 20 April 2022). [CrossRef]

- Santana, M.V.; Mirón, I.M.; Vargas, L.A.; Bedoya, J.L. Comparative Analysis of Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Among Girls and Adolescents who Perform Rhythmic Gymnastics. Rev. Bras. Med. Esporte 2019, 25, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peláez-Barrios, E.M.; Vernetta, M. Body Dissatisfaction, Mediterranean Diet Adherence and Anthropometric Data in Female Gymnasts and Adolescent. Apunts Educ. Física Deport. 2022, 149, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziólkowska, B. Ekspresja Syndromu Gotowości Anorektycznej u dziewcząt w stadium adolescencji. In Polish: Expression of the Anorexic Readiness Syndrome in Adolescence; Wydawnictwo Fundacji Humaniora: Poznań, Poland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ziółkowska, B.K.; Ocalewski, J. Anorexia Readiness Syndrome—About the Need for Early Detection of Dietary Restrictions. Pilot Study Findings. Psychiatr. Pol. 2021, 55, 1079–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziółkowska, B.; Ocalewski, J.; Dąbrowska, A. The Associations Between the Anorexic Readiness Syndrome, Familism, and Body Image Among Physically Active Girls. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 765276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. International Classification of Diseases Eleventh Revision (ICD-11); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. Available online: https://icd.who.int/en (accessed on 3 April 2022).

- APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition Text Revision (DSM-5-TR); American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rymarczyk, K. The Role of Personality Traits, Sociocultural Factors, and Body Dissatisfaction in Anorexia Readiness Syndrome in Women. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 9, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Świerczyńska, J. Coexistence of the Features of Perfectionism and Anorexia Readiness in School Youth. Psychiatr. Pol. 2020, 54, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ołpińska–Lischka, M. Assessment of Anorexia Readiness Syndrome and Body Image in Female Dancers from Poland and Germany. J. Educ. 2017, 7, 423–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalcarz, W.; Musieł, A.; Koniuszuk, K. Ocena zachowań anorektycznych tancerek w zależności od poziomu Syndromu Gotowości Anorektycznej. Pol. J. Sport. Med. Sport. 2008, 24, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Chalcarz, W.; Radzimirska-Graczyk, M.; Surosz, B. Porównanie zachowań anorektycznych gimnazjalistek ze szkół sportowych i niesportowych. Med. Sport. 2009, 25, 368–376. [Google Scholar]

- FIG-Fédération Internationale de Gymnastique. Available online: https://www.gymnastics.sport/site/rules/#8 (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Stewart, A.; Marfell-Jones, M.; Olds, T.; Ridder, H. International Standards for Anthropometric Assessment; ISAK: Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Taboada-Iglesias, Y.; Gutiérrez-Sánchez, Á.; Vernetta Santana, M. Anthropometric Profile of Elite Acrobatic Gymnasts and Prediction of Role Performance. J. Sport. Med. Phys. Fit. 2016, 56, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Catela, D.; Serôdio, M.; Seabra, A.P. Body Composition and Proportionality of Base and Top in Acrobatic Gymnastics of Young Portuguese Athletes. Open Access J. Biomed. Sci. 2020, 3, 778–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernetta Santana, M.; Ariza-Vargas, L.; Martínez-Patiño, M.; López Bedoya, J. Injury Profile in Elite Acrobatic Gymnasts Compared by Gender. J. Hum. Sport. Exerc. 2021, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merida, F.; Nista-Piccolo, V.; Merida, M. Redescobrindo a Ginástica Acrobática. Movimento 2008, 14, 155–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrione, P. No Risk of Anorexia Nervosa in Young Rhythmic Gymnasts: What are the Practical Implications of What is Already Know? J. Nutr. Disord. Ther. 2013, 3, e115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ariza-Vargas, L.; Salas-Morillas, A.; López-Bedoya, J.; Vernetta-Santana, M. Percepción de la imagen corporal en adolescentes practicantes y no practicantes de gimnasia acrobática (Perception of body image in adolescent participants and non-participants in acrobatic gymnastics). Retos 2021, 39, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, V.; Jowett, S.; Meyer, C. Eating Psychopathology amongst Athletes: The Importance of Relationships with Parents, Coaches and Teammates. Int. J. Sport. Exerc. Psychol. 2013, 11, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira Coelho, G.M.; de Abreu Soares, E.; Ribeiro, B.G. Are Female Athletes at Increased Risk for Disordered Eating and Its Complications? Appetite 2010, 55, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caine, D.; Bass, S.L.; Daly, R. Does Elite Competition Inhibit Growth and Delay Maturation in Some Gymnasts? Quite Possibly. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2003, 15, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smink, F.R.E.; van Hoeken, D.; Hoek, H.W. Epidemiology of Eating Disorders: Incidence, Prevalence and Mortality Rates. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2012, 14, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Behaviours and Attitudes Determining Anorexic Tendencies (No. in the SGA-20) | Low ARS % (N) | Medium ARS % (N) | High ARS % (N) | p | V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Losing weight methods—ARSW | |||||

| Use of fasting, diets, food restriction (1) | 0.0 (0) | 26.7 (24) | 92.3 (12) | ≤0.001 | 0.54 |

| Taking laxatives (4) | 0.0 (0) | 3.3 (3) | 7.7 (1) | 0.379 | 0.12 |

| Taking weight loss supplements/appetite suppressants (12) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 15.4 (2) | ≤0.001 | 0.41 |

| Practicing intense physical exercise (17) | 33.3 (10) | 63.3 (57) | 84.6 (11) | 0.002 | 0.30 |

| Limiting fats and carbohydrates (20) | 10.0 (3) | 73.3 (66) | 100.0 (13) | ≤0.001 | 0.60 |

| Attitudes toward eating—ARSE | |||||

| Paying attention to the quantity and quality of food in the household (10) | 3.3 (1) | 40.0 (36) | 53.8 (7) | ≤0.001 | 0.35 |

| Feeling angry after eating too much (11) | 0.0 (0) | 43.3 (39) | 100.0 (13) | ≤0.001 | 0.55 |

| Knowing the caloric value of many foods (18) | 3.3 (1) | 43.3 (39) | 100.0 (13) | ≤0.001 | 0.59 |

| Style of parenting in family—ARSP | |||||

| Feeling of being criticized/admonished/controlled by parents (5) | 0.0 (0) | 22.2 (20) | 61.5 (8) | ≤0.001 | 0.39 |

| Feeling satisfied with being the best in many areas (6) | 46.7 (14) | 86.7 (78) | 100.0 (13) | ≤0.001 | 0.44 |

| Not feeling fully accepted by parents (14) | 0.0 (0) | 2.2 (2) | 15.4 (2) | 0.019 | 0.24 |

| Perception of own attractiveness—ARSA | |||||

| Perceiving attractive appearance as a condition for achieving success in life (2) | 3.3 (1) | 47.8 (43) | 84.6 (11) | ≤0.001 | 0.47 |

| Paying considerable attention to taking care of oneself and one’s appearance (3) | 46.7 (14) | 72.2 (65) | 92.3 (12) | 0.005 | 0.28 |

| Belief that thinner women are more attractive to men (7) | 26.7 (8) | 56.7 (51) | 76.9 (10) | 0.003 | 0.30 |

| Frequent mood swings and feelings of dissatisfaction with oneself (8) | 3.3 (1) | 21.1 (19) | 46.2 (6) | 0.004 | 0.29 |

| Comparing oneself to models and attractive actresses (9) | 3.3 (1) | 21.1 (19) | 38.5 (5) | 0.016 | 0.25 |

| Seeing one’s own body as disproportionate (13) | 13.3 (4) | 14.4 (13) | 61.5 (8) | 0.001 | 0.36 |

| Monitoring one’s own weight and body size (15) | 63.3 (19) | 87.8 (79) | 100.0 (13) | 0.002 | 0.31 |

| Seeing oneself as unattractive to others (16) | 20.0 (6) | 16.7 (15) | 15.4 (2) | 0.899 | 0.04 |

| The desire to improve the appearance of one’s own body (19) | 3.3 (1) | 54.4 (49) | 92.3 (12) | ≤0.001 | 0.52 |

| Event Category | p1 | |||||

| Groups (N = 75) | Pairs (N = 58) | |||||

| ARSW | 1.5 ± 1.1 | 1.6 ± 1.1 | 0.722 | |||

| ARSE | 1.0 ± 1.1 | 1.3 ± 1.1 | 0.146 | |||

| ARSP | 1.2 ± 0.7 | 0.8 ± 0.6 | ≤0.001 | |||

| ARSA | 3.9 ± 1.7 | 3.3 ± 1.6 | 0.075 | |||

| ARSTS | 7.6 ± 3.6 | 7.0 ± 2.9 | 0.480 | |||

| Role in Partnership | p1 | |||||

| Bases (N = 69) | Tops (N = 64) | |||||

| ARSW | 1.6 ± 1.2 | 1.4 ± 1.0 | 0.211 | |||

| ARSE | 1.2 ± 1.1 | 1.0 ± 1.1 | 0.195 | |||

| ARSP | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 0.8 ± 0.6 | 0.001 | |||

| ARSA | 4.1 ± 1.6 | 3.2 ± 1.7 | 0.001 | |||

| ARSTS | 8.2 ± 3.3 | 6.4 ± 3.1 | 0.001 | |||

| Region of Residence | p2 | Post-Hoc Test* | ||||

| British Islands (N = 17) | Central Europe (N = 70) | Eastern Europe (N = 27) | North America (N = 19) | |||

| ARSW | 0.9 ± 0.8 | 1.4 ± 1.1 | 2.1 ± 1.1 | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 0.001 | EE–BI; EE–CE |

| ARSE | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 1.0 | 1.9 ± 1.1 | 0.8 ± 1.0 | ≤0.001 | CE–BI; EE–BI; EE–NA |

| ARSP | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.6 | 1.6 ± 0.8 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | ≤0.001 | EE–CE; EE–NA |

| ARSA | 2.3 ± 0.9 | 3.8 ± 1.7 | 4.6 ± 1.4 | 3.1 ± 1.6 | ≤0.001 | CE–BI; EE–BI; EE–NA |

| ARSTS | 4.2 ± 0.8 | 7.2 ± 3.1 | 10.2 ± 2.9 | 6.4 ± 2.8 | ≤0.001 | CE–BI; EE–BI; EE–CE; EE–NA |

| Low ARS (L) (N = 30) | Medium ARS (M) (N = 90) | High ARS (H) (N = 13) | p | p1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 12.5 ± 1.7; 10–17.3 | 14.1 ± 2.1; 10–19 | 16.3 ± 2.6; 11.6–18.9 | ≤0.001 | H − M = 0.040 H − L ≤ 0.001 M − L ≤ 0.001 |

| Weight (kg) | 38.6 ± 10.0; 24.1–63.3 | 46.0 ± 12.9; 22.4–75.4 | 49.8 ± 14.4; 25.9–69.1 | 0.013 | H − L = 0.040 M − L = 0.031 |

| Height (m) | 1.47 ± 0.10; 1.32–1.65 | 1.55 ± 0.12; 1.25–1.75 | 1.54 ± 0.14; 1.29–1.72 | 0.004 | M − L = 0.003 |

| WC (cm) | 60.6 ± 4.9; 53–73 | 63.7 ± 6.3; 50–80 | 64.6 ± 7.9; 50–73 | 0.028 | M − L = 0.050 |

| WHtR | 0.41 ± 0.02; 0.38–0.46 | 0.41 ± 0.02; 0.35–0.47 | 0.42 ± 0.03; 0.37–0.47 | 0.560 | - |

| BMI | 17.7 ± 2.3; 13.8–23.8 | 18.6 ± 2.8; 14.1–25.4 | 20.4 ± 3.3; 14.4–24.1 | 0.020 | H − L = 0.017 |

| Fat% | 14.6 ± 6.6; 1.9–28.1 | 17.5 ± 8.1; 1.0–35.9 | 19.3 ± 8.6, 2.6–29.7 | 0.121 | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Polak, E.; Gardzińska, A.; Zadarko-Domaradzka, M. Anorexic Readiness Syndrome in Elite Female Acrobatic Gymnasts—International Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13181. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013181

Polak E, Gardzińska A, Zadarko-Domaradzka M. Anorexic Readiness Syndrome in Elite Female Acrobatic Gymnasts—International Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(20):13181. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013181

Chicago/Turabian StylePolak, Ewa, Adrianna Gardzińska, and Maria Zadarko-Domaradzka. 2022. "Anorexic Readiness Syndrome in Elite Female Acrobatic Gymnasts—International Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 20: 13181. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013181

APA StylePolak, E., Gardzińska, A., & Zadarko-Domaradzka, M. (2022). Anorexic Readiness Syndrome in Elite Female Acrobatic Gymnasts—International Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13181. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013181