Research on the Influence Mechanisms of the Affective and Cognitive Self-Esteem

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Types of SMU

1.2. Social Media and Loneliness

1.3. Objective Social Isolation

1.4. Self-Esteem

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Techniques

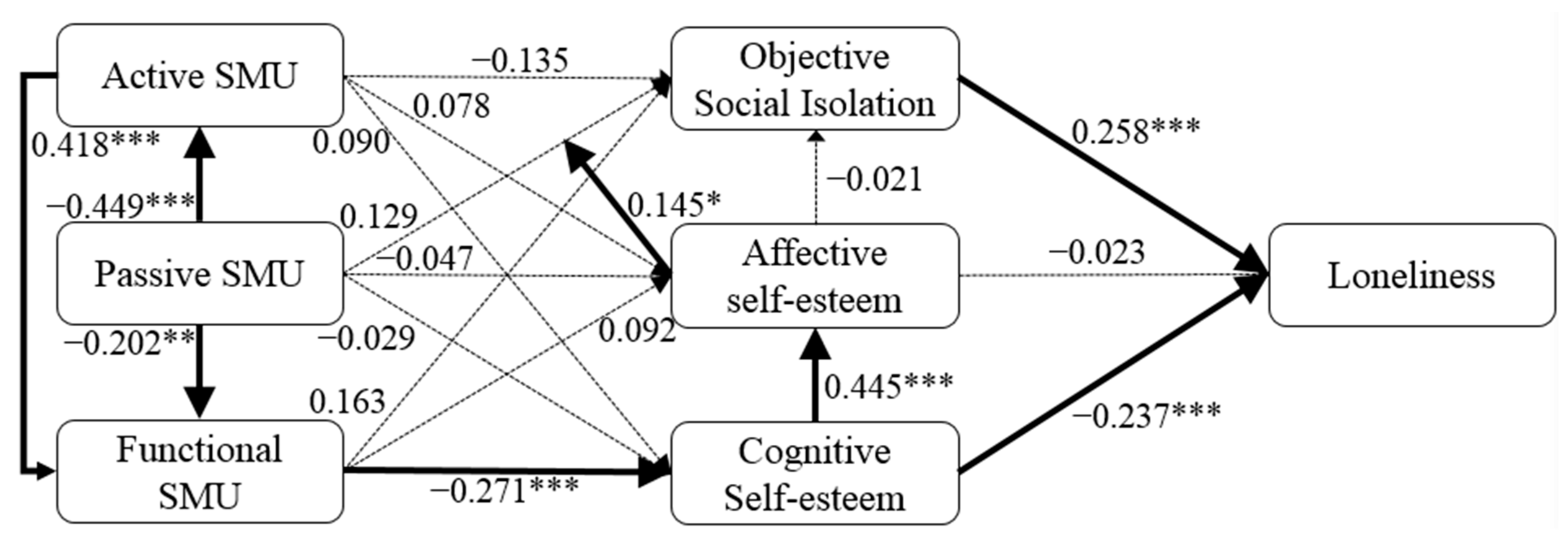

3. Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

5. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dahlberg, L.; Agahi, N.; Lennartsson, C. Lonelier than ever? Loneliness of older people over two decades. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2018, 75, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanratty, B.; Stow, D.; Collingridge Moore, D.; Valtorta, N.K.; Matthews, F. Loneliness as a risk factor for care home admission in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Age Ageing 2018, 47, 896–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cattan, M.; White, M.; Bond, J.; Learmouth, A. Preventing social isolation and loneliness among older people: A systematic review of health promotion interventions. Ageing Soc. 2005, 25, 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McHugh Power, J.E.; Steptoe, A.; Kee, F.; Lawlor, B.A. Loneliness and social engagement in older adults: A bivariate dual change score analysis. Psychol. Aging 2019, 34, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Gabalawy, R.; Mackenzie, C.S.; Thibodeau, M.A.; Asmundson, G.J.G.; Sareen, J. Health anxiety disorders in older adults: Conceptualizing complex conditions in late life. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 33, 1096–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, M.M.; Burgermaster, M.; Mamykina, L. The use of social media in nutrition interventions for adolescents and young adults-A systematic review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2018, 120, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Kleinman, M.; Mertz, J.; Brannick, M. Is social network site usage related to depression? A meta-analysis of Facebook-depression relations. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 248, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, R.L.; Rickwood, D.J. A systematic review of the mental health outcomes associated with Facebook use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 76, 576–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabrook, E.M.; Kern, M.L.; Rickard, N.S. Social Networking Sites, Depression, and Anxiety: A Systematic Review. JMIR Ment. Health 2016, 3, e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baker, D.A.; Algorta, G.P. The Relationship Between Online Social Networking and Depression: A Systematic Review of Quantitative Studies. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2016, 19, 638–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H. Psychological issues and problematic use of smartphone: ADHD’s moderating role in the associations among loneliness, need for social assurance, need for immediate connection, and problematic use of smartphone. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 80, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, G.G.; Boyle, E.A.; Czerniawska, K.; Courtney, A. Posting photos on Facebook: The impact of Narcissism, Social Anxiety, Loneliness, and Shyness. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018, 133, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, K.; Frison, E.; Eggermont, S.; Vandenbosch, L. Active public Facebook use and adolescents’ feelings of loneliness: Evidence for a curvilinear relationship. J. Adolesc. 2018, 67, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentina, E.; Chen, R. Digital natives’ coping with loneliness: Facebook or face-to-face? Inf. Manag. 2019, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reissmann, A.; Hauser, J.; Stollberg, E.; Kaunzinger, I.; Lange, K.W. The role of loneliness in emerging adults’ everyday use of facebook—An experience sampling approach. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 88, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Yang, H. Loneliness and the use of social media to follow celebrities: A moderating role of social presence. Soc. Sci. J. 2019, 56, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blachnio, A.; Przepiorka, A.; Boruch, W.; Balakier, E. Self-presentation styles, privacy, and loneliness as predictors of Facebook use in young people. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 94, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deters, F.G.; Mehl, M.R. Does Posting Facebook Status Updates Increase or Decrease Loneliness? An Online Social Networking Experiment. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2013, 4, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sutcliffe, A.G.; Binder, J.F.; Dunbar, R.I.M. Activity in social media and intimacy in social relationships. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 85, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chopik, W.J. The Benefits of Social Technology Use Among Older Adults Are Mediated by Reduced Loneliness. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2016, 19, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phu, B.; Gow, A.J. Facebook use and its association with subjective happiness and loneliness. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 92, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman, M.; Reich, B. Social media and loneliness: Why an Instagram picture may be worth more than a thousand Twitter words. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 62, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, Y.M.; Bae, Y.; Jang, H. Social and parasocial relationships on social network sites and their differential relationships with users’ psychological well-being. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2013, 16, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, Y.; Song, H.; Vorderer, P. Why do people post and read personal messages in public? The motivation of using personal blogs and its effects on users’ loneliness, belonging, and well-being. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 1626–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Velden, P.G.; Setti, I.; van der Meulen, E.; Das, M. Does social networking sites use predict mental health and sleep problems when prior problems and loneliness are taken into account? A population-based prospective study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 93, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, A.; Konig, H.H. The association between use of online social networks sites and perceived social isolation among individuals in the second half of life: Results based on a nationally representative sample in Germany. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aarts, S.; Peek, S.T.; Wouters, E.J. The relation between social network site usage and loneliness and mental health in community-dwelling older adults. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2015, 30, 942–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorisdottir, I.E.; Sigurvinsdottir, R.; Asgeirsdottir, B.B.; Allegrante, J.P.; Sigfusdottir, I.D. Active and Passive Social Media Use and Symptoms of Anxiety and Depressed Mood Among Icelandic Adolescents. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2019, 22, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnell, K.; George, M.J.; Vollet, J.W.; Ehrenreich, S.E.; Underwood, M.K. Passive social networking site use and well-being: The mediating roles of social comparison and the fear of missing out. Cyberpsychology: J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Escobar-Viera, C.G.; Shensa, A.; Bowman, N.D.; Sidani, J.E.; Knight, J.; James, A.E.; Primack, B.A. Passive and Active Social Media Use and Depressive Symptoms Among United States Adults. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2018, 21, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerson, J.; Plagnol, A.C.; Corr, P.J. Passive and Active Facebook Use Measure (PAUM): Validation and relationship to the Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 117, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frison, E.; Eggermont, S. Exploring the Relationships Between Different Types of Facebook Use, Perceived Online Social Support, and Adolescents Depressed Mood. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2015, 34, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertegal-Vega, M.Á.; Oliva-Delgado, A.; Rodríguez-Meirinhos, A. Systematic review of the current state of research on Online Social Networks: Taxonomy on experience of use. Comunicar. Media Educ. Res. J. 2019, 27, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burke, M.; Marlow, C.; Lento, T. Social network activity and social well-being. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Atlanta, GA, USA, 10–15 April 2010; pp. 1909–1912. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, M.; Kraut, R.; Marlow, C. Social capital on facebook. In Proceedings of the 2011 Annual Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems-CHI ‘11, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 7–12 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- de Jong Gierveld, J. A review of loneliness: Concept and definitions, determinants and consequences. Rev. Clin. Gerontol. 1998, 8, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mahoney, J.; Le Moignan, E.; Long, K.; Wilson, M.; Barnett, J.; Vines, J.; Lawson, S. Feeling alone among 317 million others: Disclosures of loneliness on Twitter. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 98, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailis, D.S.; Chipperfield, J.G.; Perry, R.P. Optimistic Social Comparisons of Older Adults Low in Primary Control: A Prospective Analysis of Hospitalization and Mortality. Health Psychol. 2005, 24, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correa, T.; Hinsley, A.W.; de Zúñiga, H.G. Who interacts on the Web?: The intersection of users’ personality and social media use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatters, L.M.; Taylor, H.O.; Nicklett, E.J.; Taylor, R.J. Correlates of Objective Social Isolation from Family and Friends among Older Adults. Healthcare 2018, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, Y.; Ko, Y.-g. Feeling lonely when not socially isolated: Social isolation moderates the association between loneliness and daily social interaction. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2017, 35, 1340–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, J. Training social skills in groups of depressive elderly patients: Experiences of a day clinic for gerontopsychiatry and psychotherapy. Gruppenpsychother. Gruppendyn. 2004, 40, 130–147. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, D.H.; Noh, G.Y. The influence of social media use on attitude toward suicide through psychological well-being, social isolation, and social support. Info. Commun. Soc. 2020, 23, 1427–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshi, D.; Cotten, S.R.; Bender, A.R. Problematic Social Media Use and Perceived Social Isolation in Older Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. Gerontology 2020, 66, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, H.F.; Li, X.M.; Chi, P.L.; Zhao, S.R.; Zhao, J.F. Loneliness and self-Esteem in children and adolescents affected by parental HIV: A 3-year longitudinal study. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 2019, 11, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gonzalez-Marin, P.; Puig-Barrachina, V.; Cortes-Franch, I.; Bartoll, X.; Artazcoz, L.; Malmusi, D.; Clotet, E.; Daban, F.; Diez, E.; Cardona, A.; et al. Social and material determinants of health in participants in an active labor market program in Barcelona. Arch. Public Health 2018, 76, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapia, A.J.; Barrios, L.M.; Gonzalez-Forteza, C. Self-esteem, depressive symptomatology, and suicidal ideation in adolescents: Results of three studies. Salud Ment. 2007, 30, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Creemers, D.H.M.; Scholte, R.H.J.; Engels, R.; Prinstein, M.J.; Wiers, R.W. Implicit and explicit self-esteem as concurrent predictors of suicidal ideation, depressive symptoms, and loneliness. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2012, 43, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghafri, R.K.; Al-Badi, A.H. The Effect of Social Media on Self-Esteem. In Proceedings of the 27th International Business Information Management Association Conference, Milan, Italy, 4–5 May 2016; pp. 3228–3237. [Google Scholar]

- van Eldik, A.K.; Kneer, J.; Jansz, J. Urban & Online: Social Media Use among Adolescents and Sense of Belonging to a Super-Diverse City. Media Commun. 2019, 7, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djafarova, E.; Trofimenko, O. Exploring the relationships between self-presentation and self-esteem of mothers in social media in Russia. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 73, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivadeneyra, R.; Ward, L.M.; Gordon, M. Distorted reflections: Media exposure and Latino adolescents’ conceptions of self. Media Psychol. 2007, 9, 261–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strubel, J.; Petrie, T.A.; Pookulangara, S. “Like” Me: Shopping, Self-Display, Body Image, and Social Networking Sites. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 2018, 7, 328–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuh, J. The Relationship between Loneliness and Smartphone Addiction Symptoms among Middle School Students: Testing the Mediating Role of Self-Esteem. Korean J. Youth Stud. 2016, 23, 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaksen, K.J.; Roper, S. The commodification of self-Esteem: Branding and british teenagers. Psychol. Mark. 2012, 29, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dancer, L.S. On the multidimensional structure of self-esteem: Facet analysis of Rosenberg’s self-esteem scale. In Facet Theory; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 223–236. [Google Scholar]

- Nisar, T.M.; Prabhakar, G.; Ilavarasan, P.V.; Baabdullah, A.M. Facebook usage and mental health: An empirical study of role of non-directional social comparisons in the UK. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 48, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, W. The Effect of Wording Effects on Factor Structure of Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Master’s Thesis, Guizhou Normal University, Guiyang, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kanten, P.; Kanten, S. The antecedents of procrastination behavior: Personality characteristics, self-esteem and self-efficacy. In Proceedings of the Global Business Research Congress (GBRC), Istanbul, Turkey, 26–27 May 2016; pp. 331–341. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.G.; Bookstein, F.L. Two structural equation models: LISREL and PLS applied to consumer exit-voice theory. J. Mark. Res. 1982, 19, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Willaby, H.W.; Costa, D.S.J.; Burns, B.D.; MacCann, C.; Roberts, R.D. Testing complex models with small sample sizes: A historical overview and empirical demonstration of what partial least squares (PLS) can offer differential psychology. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 84, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malhotra, N.K.; Kim, S.S.; Patil, A. Common method variance in is research: A comparison of alternative approaches and a reanalysis of past research. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 1865–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T.K.; Henseler, J. Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Quart. 2015, 39, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zheng, D.Q.; Huang, L.; Kim, K.J. How ambidextrous social networking service users balance different social capital benefits: An evidence from WeChat. Internet Res. 2021, 31, 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verduyn, P.; Ybarra, O.; Resibois, M.; Jonides, J.; Kross, E. Do Social Network Sites Enhance or Undermine Subjective Well-Being? A Critical Review. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2017, 11, 274–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cronbach’s Alpha | RHO_A | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASMU | 0.918 | 0.918 | 0.960 | 0.924 |

| PSMU | 0.901 | 0.907 | 0.931 | 0.771 |

| FSMU | 0.623 | 0.637 | 0.840 | 0.725 |

| OSI | 0.774 | 0.777 | 0.899 | 0.816 |

| CE | 0.623 | 0.652 | 0.802 | 0.581 |

| AE | 0.648 | 0.650 | 0.810 | 0.588 |

| LN | 0.823 | 0.866 | 0.893 | 0.737 |

| ASMU | PSMU | FSMU | OSI | CE | AE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSMU | 0.493 | |||||

| FSMU | 0.677 | 0.496 | ||||

| OSI | 0.168 | 0.144 | 0.218 | |||

| CE | 0.149 | 0.170 | 0.358 | 0.118 | ||

| AE | 0.169 | 0.134 | 0.084 | 0.126 | 0.675 | |

| LN | 0.106 | 0.198 | 0.175 | 0.330 | 0.337 | 0.163 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, S.; Zhang, M. Research on the Influence Mechanisms of the Affective and Cognitive Self-Esteem. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13232. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013232

Yang S, Zhang M. Research on the Influence Mechanisms of the Affective and Cognitive Self-Esteem. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(20):13232. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013232

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Shufang, and Mingyao Zhang. 2022. "Research on the Influence Mechanisms of the Affective and Cognitive Self-Esteem" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 20: 13232. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013232