The Effect of the KDL Active School Plan on Children and Adolescents’ Physical Fitness in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

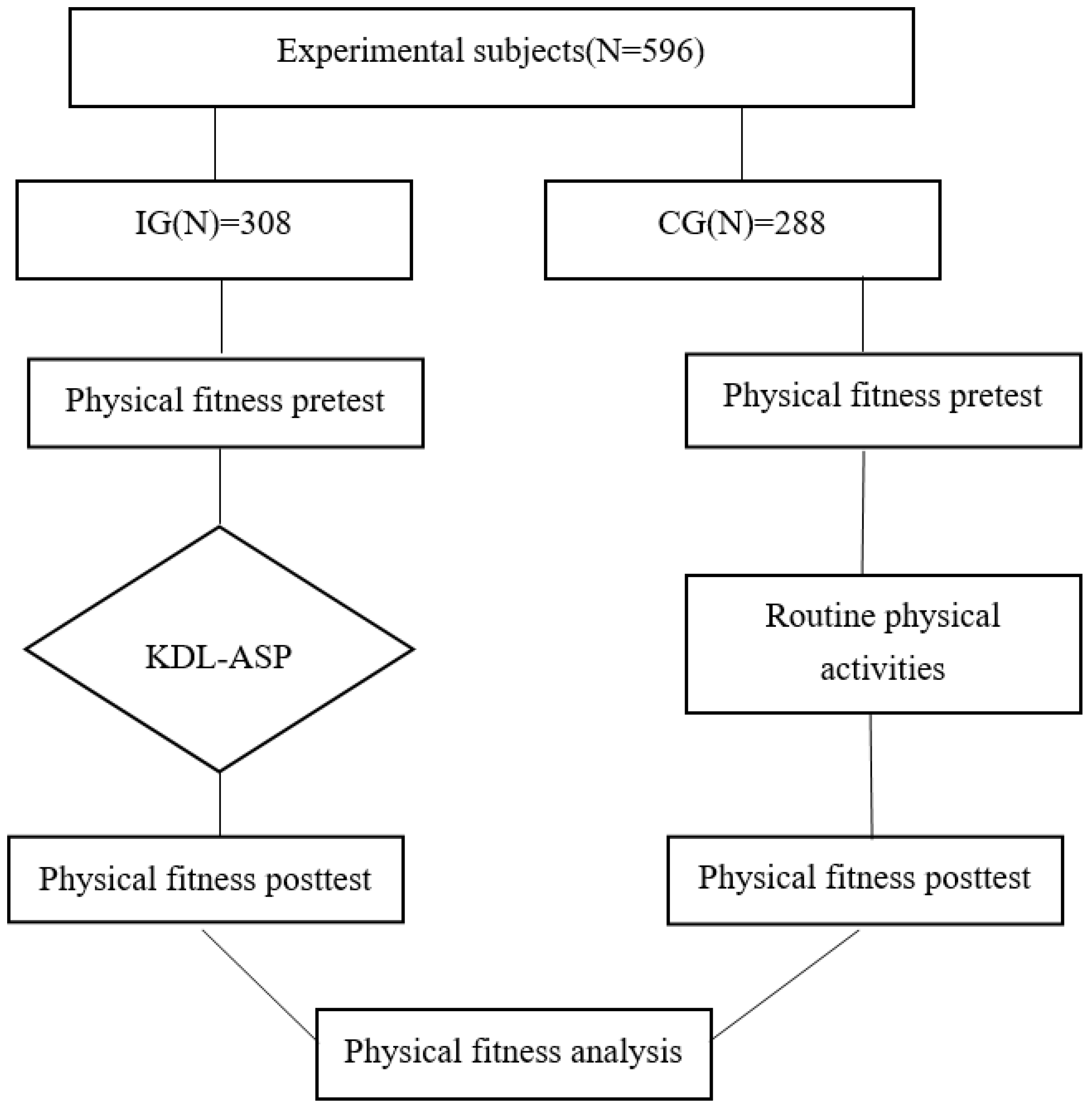

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

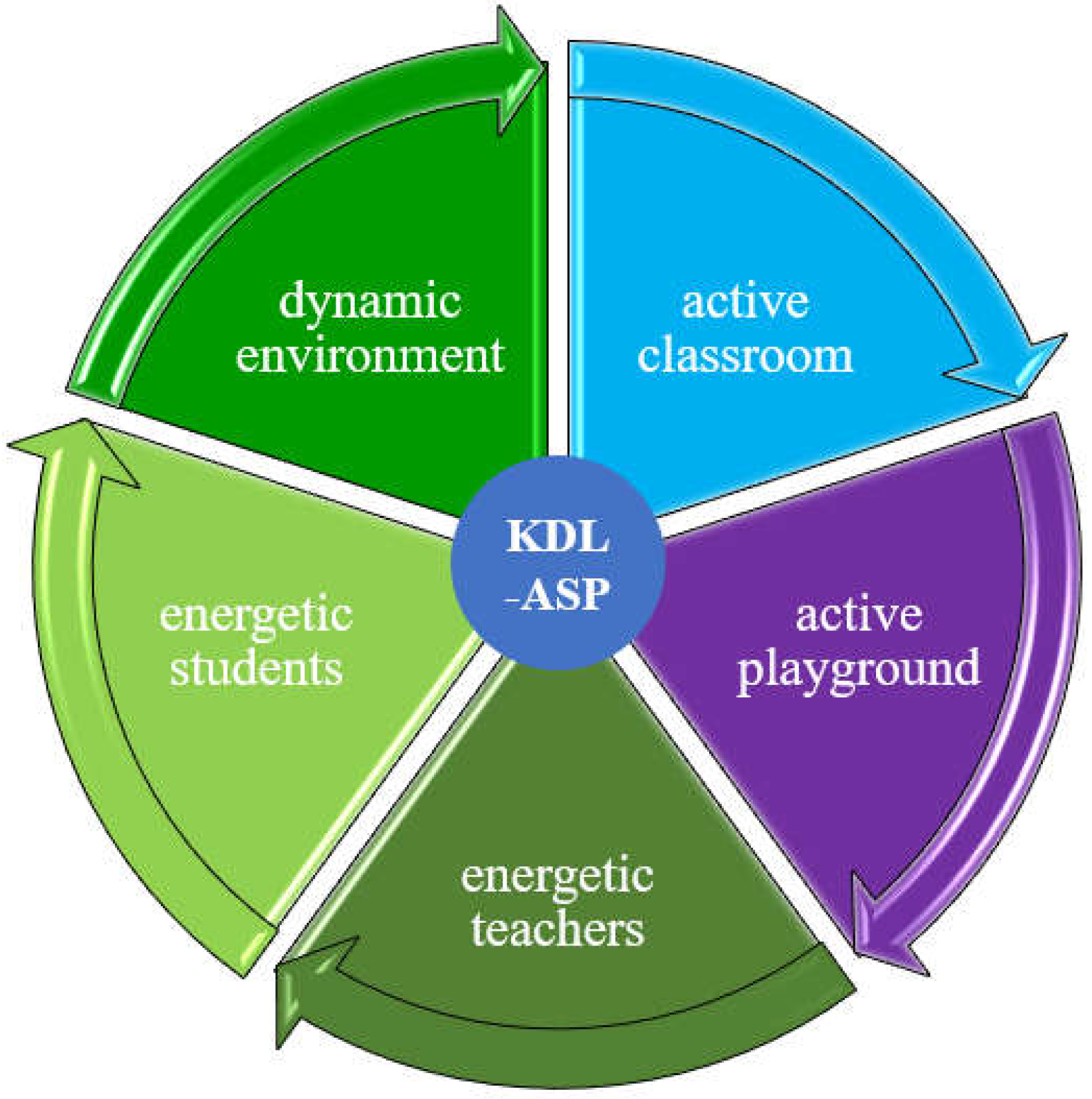

2.3. Intervention Procedures

2.4. Teaching Training

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Impact of Physical Fitness Total Scores Improvement for Children and Adolescents

3.2. Different Levels and Genders’ Progress in Some Indexes between IG and CG

3.3. The Progress of Physical Fitness Indexes for Boys and Girls at Different Levels

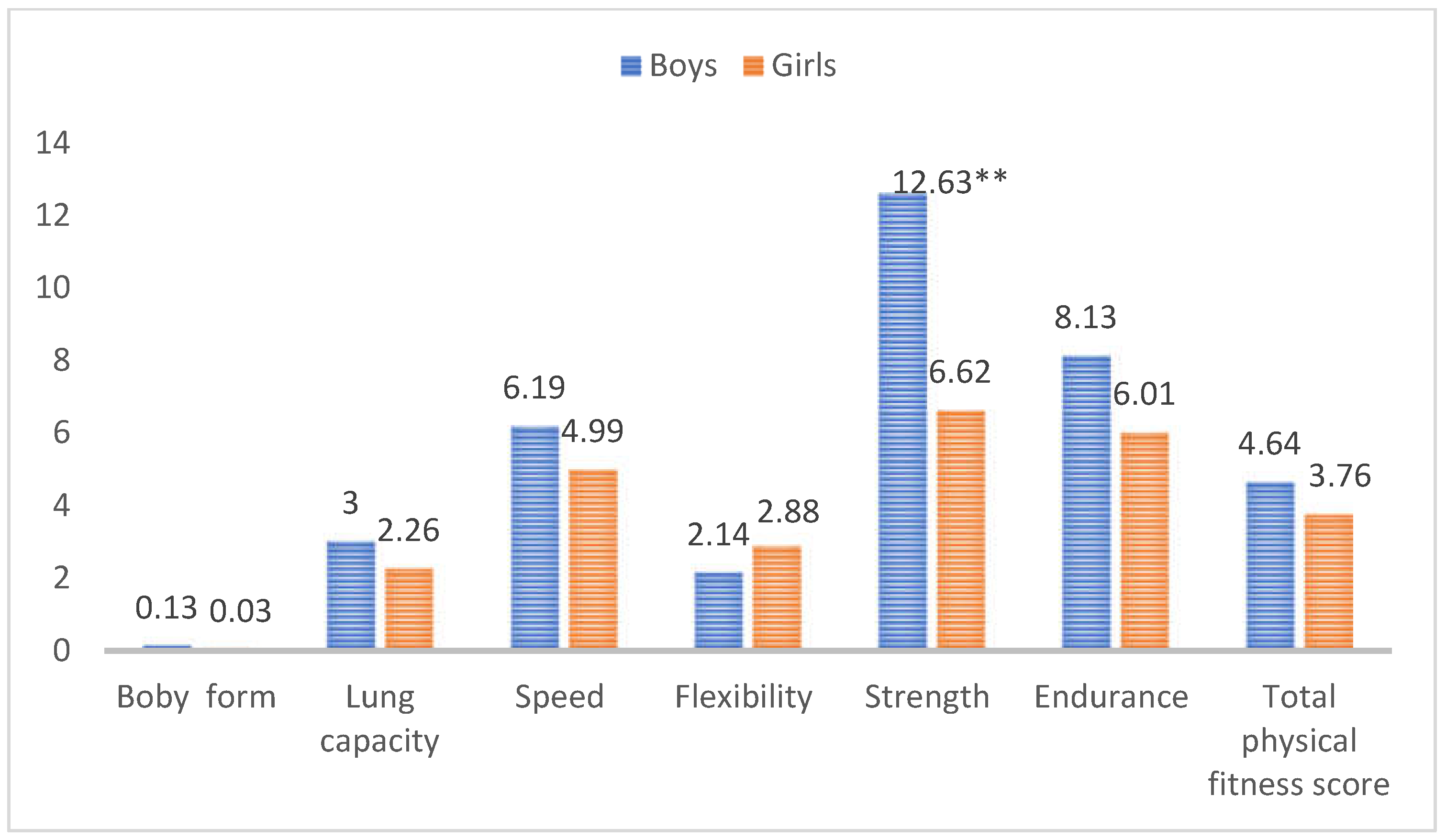

3.4. The Progress of Physical Fitness Indexes of Children and Adolescents between Different Gender

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ortega, F.B.; Ruiz, J.R.; Castillo, M.J.; Sjöström, M. Physical fitness in childhood and adolescence: A powerful marker of health. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z. Prevalence of Physical Activity and Physical Fitness among Chinese Children and Adolescents aged 9–17 Years Old. Ph.D. Thesis, Shanghai University of Sport, Shanghai, China, June 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, S.S.-C.; Zhang, R.; Suzuki, K.; Naito, H.; Balasekaran, G.; Song, J.K.; Park, S.Y.; Liou, Y.-M.; Lu, D.J.; Poh, B.K.; et al. Physical activity and health-related fitness in Asian adolescents: The Asia-fit study. J. Sport. Sci. 2020, 38, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: A pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1.6 million participants. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekelund, U.; Tarp, J.; Steene-Johannessen, J.; Hansen, B.H.; Jefferis, B.; Fagerland, M.W.; Whincup, P.; Diaz, K.M.; Hooker, S.P.; Chernofsky, A.C.; et al. Dose-response associations between accelerometry measured physical activity and sedentary time and all cause mortality: Systematic review and harmonised meta-analysis. BMJ 2019, 366, l4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healthy China Action Promotion Committee. Healthy China Action (2019–2030). Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2019-07/15/content_5409694.htm (accessed on 16 September 2022).

- Cao, L.Y.; Shi, B. Enlightenment of National Fitness Monitoring Results to School Physical Education. In Proceedings of the 11th National Sports Science Congress, Nanjing, China, 1–3 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, F.B.; Mao, Z.M.; Cheng, T.Y.; Chen, S. “Health China 2030 Program” and School P.E. Reform Strategies (3): For Ensuring No Less than One Hour Physical Activity for Students Per Day. J. Wuhan Inst. Phys. Educ. 2018, 52, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyunwoo, J.; Stacey, P.; David, K. Policy for physical education and school sport in England, 2003–2010: Vested interests and dominant discourses. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2016, 21, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, R.L.; Castelli, D.M.; Beighle, A.; Erwin, H. School-Based Physical Activity Promotion: A Conceptual Framework for Research and Practice. Child. Obes. 2014, 10, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Z. Implementing the physical education and health curriculum standards, realizing high-quality classroom teaching-approaching the KDL physical education and health curriculum. China Sch. Sport. 2019, 4, 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.S. An Experimental Study on the Effect of KDL Game on the Development of Rural Children’s Gross Movements. Master’s Thesis, Yunnan Normal University, Kunming, China, May 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.H.; Zhang, S.P.; Zheng, H.F.; Yin, X.J.; Liang, C.; Chen, N. The influence of KDL curriculum on children’s basic motor skills and physical health level. J. Phys. Educ. 2021, 28, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.F. Experimental Research on the Teaching of Basketball Based on the Concept of KDL Sports and Health Curriculum in Junior Middle School. Master’s Thesis, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China, October 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological systems theory. In Six Theories of Child Development: Revised Formulations and Current Issues; Vasta, R., Ed.; Jessica Kingsley: London, UK, 1992; pp. 187–248. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska, J.O.; DiClemente, C.C. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1983, 51, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfon, N.; Forrest, C.B.; Lerner, R.M.; Faustman, E.M. Handbook of Life Course Health Development; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 18–43. ISBN -13: 978-3-319-47141-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. Compulsory Education Curriculum Standards for Physical Education and Health (Edition 2011); Beijing Normal University Press: Beijing, China, 2011; p. 4. ISBN 9787303133079. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education. Notice of General Administration of Sport on the implementation of the “National Physical Fitness Standards for Students”. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A17/moe_943/moe_947/200704/t20070404_80275.html (accessed on 28 September 2022).

- Committee on Interpretation of National Students’ Physical Fitness Standards. Interpretation of National Students’ Physical Fitness Standards; People’s Education Press: Beijing, China, 2007; pp. 111–126. ISBN 9787107203657. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, P.; Zhi, E.L.; Zhang, W.C.; Sui, L. Promotion of Physical Exercise Intervention Programs on Students’ Physical and Mental Quality in Primary and Middle Schools. China Sport Sci. Techsology 2012, 48, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: New York, NY, USA, 1988; ISBN 9780203771587. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Eta-squared and partial eta-squared in fixed factor ANOVA designs. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1973, 33, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Chen, S.L.; Fang, Q.H. Research Progress and Implications of the United States Comprehensive School Physical Activity Program (CSPAP). J. Beijing Sport Univ. 2019, 42, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messing, S.; Rütten, A.; Abu-Omar, K.; Ungerer-Röhrich, U.; Goodwin, L.; Burlacu, I.; Gediga, G. How can physical activity be promoted among children and adolescents? A systematic review of reviews across settings. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.Z.; A, Y.G.; Chen, P.Y.; Wang, Z.Y. Correlates of Physical Activity of Children and Adolescents: A System Review of Studies in Recent 25 Years. China Sport Sci. Technol. 2022, 58, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, X.S. An Experimental Study on the Effects of Comprehensive Intervention on the Physical Health of Primary School Based on the Home-School Linkage. Phys. Educ. 2021, 41, 76–79. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.Z.; Yang, Y.G.; Kong, L.; Tong, T.T.; Chen, M.Y. A Study on the Development Strategy for Children and Adolescents’ Sports Health Promotion in China. J. Chengdu Sport Univ. 2020, 46, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Luo, D.M.; Hu, P.J.; Yan, X.J.; Zhang, J.S.; Lei, Y.T.; Zhang, B.; Ma, J. Trends of prevalence of excellent health status and physical fitness among Chinese Han students aged 13 to 18 years from 1985 to 2014. J. Peking Univ. Med. Ed. 2020, 52, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.C. Sports Anatomy; High Education Press: Beijing, China, 2010; ISBN 9787040296167. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Z.M.; Ye, L.; Ding, T.C.; Qiu, L.L. Research on Intervention Strategies of Improving Students’ Physique by School Physical Education in New Era from the Perspective of “Three Precision”. J. TUS 2022, 37, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.J. The Changing Characteristics of Physical Quality in the Sensitive Period of Children and Adolescents. Master’s Thesis, Beijing Sport University, Beijing, China, May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, A.K. Physiological Basis of Physical Fitness. Available online: https://wenku.baidu.com/view/6ebf6416227916888486d770.html (accessed on 18 January 2022).

- Wang, W.X. New Concept of Physical Training for Contemporary Children and Adolescents. In Proceedings of the Chinese Young Children’s Physical Coach Certification Training, Guangzhou, China, 24–28 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhen, Z.P.; Li, H.R.; Chen, Q.X.; Wang, R.H.; Zhang, Y.M.; Wan, X. Since the Reform and Opening Up, the Physical Fitness of Chinese Students has Developed Research on the Trend of Change in Sensitive Periods. J. BNU Nat. Sci. Ed. 2021, 57, 283–293. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.Q.; Tang, Y. PE Examination in the Senior High School Entrance Examination: Functions, Problems and Solutions. J. Beijing Sport Univ. 2021, 44, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.T. Experimental Study on the Influence of Campus Football on the Physical Health of Primary School Students. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an Physical Education University, Xi’an, China, June 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.J. Study on Physical Fitness of Han Students Aged 7–18 in Gansu Province—Take 2010–2014 as An Example. Sport. Sci. Technol. Lit. Bull. 2020, 28, 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Xu, Q.P. An experimental study on the influence of “Dynamic Campus” Action Plan on students’ interest in physical education. Phys. Educ. 2018, 38, 58–59. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.A.; Yin, R.B.; Liu, J.H.; Chen, P.Y. Correlation Study on Participation Factors of Leisure Sports of Middle School Students of Different Gender. J. Chengdu Sport Univ. 2017, 43, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.F.; Wang, H.J.; Wang, D.T.; Su, C.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, H.R.; Ou-Yang, Y.F.; Zhang, B. Analysis of physical activity and sedentary behaviors in children and adolescents from 12 provinces /municipalities in China. J. Hyg. Res. 2016, 45, 394–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulkes, J.D.; Knowles, Z.; Fairclough, S.J.; Stratton, G.; O’Dwyer, M.; Ridgers, N.D.; Foweather, L. Fundamental Movement Skills of Preschool Children in Northwest England. Percept. Mot. Ski. Phys. Dev. Meas. 2015, 121, 260–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, B. An Evaluation of Preschool Children’s Physical Activity within Indoor Preschool Play Environments. Master’s Thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Level | Grade | Gender | IG | CG | Total | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 2 | 3rd grade | Boys | 20 | 15 | 74 | 12.4% |

| Girls | 20 | 19 | ||||

| Level 3 | 5th grade | Boys | 24 | 25 | 91 | 15.3% |

| Girls | 22 | 20 | ||||

| Level 4 | 7th grade | Boys | 19 | 22 | 82 | 13.8% |

| Girls | 23 | 18 | ||||

| 8th grade | Boys | 25 | 20 | 91 | 15.3% | |

| Girls | 25 | 21 | ||||

| 9th grade | Boys | 31 | 26 | 108 | 18.1% | |

| Girls | 25 | 26 | ||||

| Level 5 | 11th grade | Boys | 40 | 44 | 150 | 25.1% |

| Girls | 34 | 32 | ||||

| Total | Boys | 159 | 152 | 596 | 100% | |

| Girls | 149 | 136 |

| Physical Fitness | Test Items | Test Equipment |

|---|---|---|

| Body form | Body Mass Index abc | Height and weight instruments |

| Lung capacity | Lung capacity (mL) abc | Automatic Electronic Spirometer |

| Speed | 50 m running (s) abc | Stopwatch; Starting flag; Whistle |

| Flexibility | Sit and reach (cm) abc | Sit and reach tester |

| Strength | 1 min sit-ups (number) abc | Stopwatch; Exercise mat |

| 1 min pull-ups (number) c | Horizontal bar | |

| Endurance | 50 × 8 shuttle running (m/s) b | Stopwatch; Starting flag; Whistle |

| 1000/800 m (m/s) c | Stopwatch; Starting flag |

| Active Factor | Exercise Contents | Specific Modalities |

|---|---|---|

| Active classroom | Brain break in academic subjects | Invent or imitate video movements in Chinese, mathematics, and foreign language subjects every day for 3–5 min involving low- to moderate-intensity physical activities. |

| Active playground | KDL PE curriculum | The process in a physical education class was:

|

| Active aerobic exercise | Create rhythmic exercises with the characteristics of their school and promote them in recess activities to improve students’ physical fitness comprehensively. | |

| Campus Guinness challenge | According to the students’ level, PE teachers determine the Guinness records of students at different ages and organize a “challenge qualification competition” involving rope skipping, shuttlecock kicking, and other sports. The selected students will be eligible to challenge for the record. The “3 + 1” cycle (three weeks of practice, one week of competition) rotation mode is adopted. Students will constantly refresh their personal best record after a competition. At the end of the semester, the students with the highest records in each sport are awarded accordingly. | |

| Sport group challenge | Play basketball, football, table tennis, martial arts, and other sports that the students choose according to their interests for 30 min every week. At the end of each month, there is a peer challenge in the class. At the end of each semester, organize a sport challenge in the grade, and according to the results of the challenge promote the students’ health. | |

| Energetic teachers | Walking outdoors with teachers | According to the different grades of the teachers, the school regularly organizes outdoor hiking activities for teachers and staff, and the hiking distance is 5 km each time. |

| Energetic students | Parent–child carnival | With the school as the venue, students of the same grade and their parents are recruited to participate in the sports carnival every month. The content of the activities is primarily fun track and field games, and the winners will be given material rewards at the end of the activity. |

| Dynamic environment | Sport and health promotion campaign | Post periodically on the class bulletin board and propaganda board about physical health. |

| Exercise Frequency | Duration | Exercise Contents | Exercise Intensity (HRmean) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 time/day | 20 min × 1 | Actively aerobic exercise | (220–age) × (60–80%) |

| 4 times/week (elementary school) 3 times/week (junior high school and high school) | 40 min × 4 40 min × 3 | KDL curriculum | 125–140 times/minute 140–160 times/minute |

| 1 time/day | 3–5 min × 1 | Brain break in academic subjects | 100–130 times/minute |

| 3 times/week | 30 min × 3 | Campus Guinness challenge; Sport group challenge | Over 160 times/minute |

| 1 time/week | 30 min × 1 | Walking outdoors with teachers | (220–age) × (60–80%) |

| 1 time/month | 60 min × 1 | Parent–child carnival | (220–age) × (60–80%) |

| Level | Physical Fitness Weight Calculation Formula |

|---|---|

| Level 2 | Standard weight for height × 0.2 + sit-ups × 0.4 + 50 m running × 0.4 |

| Level 3 | Standard weight for height × 0.1 + lung capacity × 0.2 + 50 × 8 shuttle running × 0.3 + sit-ups × 0.2 + 50 m running × 0.2 |

| Levels 4 and 5 | Standard weight for height × 0.1+ lung capacity × 0.2 + 1000/800 m × 0.3 + sit-ups/pull-ups × 0.2 + 50 m running × 0.2 |

| Source of Variation | Type Sum of Squares | Degree of Freedom | MS | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correct model | 1725.462 a | 15 | 115.031 | 4.933 | 0.000 |

| Intercept | 7515.129 | 1 | 7515.129 | 322.312 | 0.000 |

| Level | 41.192 | 3 | 13.731 | 0.589 | 0.622 |

| Intervention | 280.481 | 1 | 280.481 | 12.029 | 0.001 ** |

| Sex | 114.563 | 1 | 114.563 | 4.913 | 0.027 * |

| Level × Intervention | 673.511 | 3 | 224.504 | 9.629 | 0.000 ** |

| Level × Sex | 72.902 | 3 | 24.301 | 1.042 | 0.373 |

| Intervention × Sex | 0.143 | 1 | 0.143 | 0.006 | 0.938 |

| Level × Intervention × Sex | 33.349 | 3 | 11.116 | 0.477 | 0.699 |

| Error | 12217.760 | 524 | 23.316 | ||

| Total | 21908.150 | 540 | |||

| Revised total | 13943.222 | 539 |

| Level/Sex | Index (Progress) | Category | N | M ± SD | T | p | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2/Girls | Speed | IG | 20 | 8.75 ± 3.683 | 2.442 | 0.019 * | 0.782 |

| CG | 19 | 5.95 ± 3.472 | |||||

| Total physical fitness score | IG | 20 | 4.92 ± 2.379 | 2.368 | 0.023 * | 0.764 | |

| CG | 19 | 3.30 ± 1.827 | |||||

| 3/Girls | Endurance | IG | 22 | 3.91 ± 2.180 | 2.048 | 0.047 * | 0.637 |

| CG | 20 | 2.65 ± 1.755 | |||||

| 4/Boys | Strength | IG | 75 | 16.91 ± 17.762 | 4.043 | 0.000 ** | 0.675 |

| CG | 68 | 5.82 ± 14.997 | |||||

| Endurance | IG | 75 | 11.56 ± 18.265 | 2.477 | 0.014 * | 0.412 | |

| CG | 68 | 4.88 ± 13.840 | |||||

| Total physical fitness score | IG | 75 | 4.73 ± 6.629 | 2.261 | 0.05 * | 0.377 | |

| CG | 68 | 2.18 ± 6.895 | |||||

| 4/Girls | Flexibility | IG | 73 | 3.75 ± 7.808 | 4.335 | 0.000 ** | 0.741 |

| CG | 65 | −1.75 ± 7.022 | |||||

| Strength | IG | 73 | 5.71 ± 10.560 | 4.820 | 0.000 ** | 0.811 | |

| CG | 65 | −1.49 ± 6.778 | |||||

| Total physical fitness score | IG | 73 | 3.42 ± 4.799 | 3.319 | 0.001 ** | 0.565 | |

| CG | 65 | 0.70 ± 4.83 |

| Sex | Index (Progress) | Level | N | M ± SD | F | p | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | Lung capacity | 2 | 20 | 3.60 ± 0.821 | 13.938 | 0.000 ** | 0.212 |

| 3 | 24 | 5.42 ± 4.413 | |||||

| 4 | 75 | 0.56 ± 1.298 | |||||

| 5 | 40 | 6.88 ± 11.111 | |||||

| Strength | 2 | 20 | 7.55 ± 3.220 | 3.384 | 0.020 * | 0.061 | |

| 3 | 24 | 6.42 ± 2.104 | |||||

| 4 | 75 | 16.91 ± 17.762 | |||||

| 5 | 40 | 10.88 ± 23.322 | |||||

| Endurance | 3 | 24 | 3.29 ± 2.404 | 4.693 | 0.011 * | 0.065 | |

| 4 | 75 | 11.56 ± 18.265 | |||||

| 5 | 40 | 4.60 ± 9.243 | |||||

| Girls | Speed | 2 | 20 | 8.75 ± 3.683 | 7.222 | 0.000 ** | 0.130 |

| 3 | 22 | 7.77 ± 4.659 | |||||

| 4 | 73 | 4.32 ± 6.794 | |||||

| 5 | 34 | 2.41 ± 4.704 | |||||

| Lung capacity | 2 | 20 | 5.65 ± 2.159 | 8.631 | 0.000 ** | 0.152 | |

| 3 | 22 | 3.64 ± 4.562 | |||||

| 4 | 73 | 0.31 ± 0.116 | |||||

| 5 | 34 | 4.21 ± 10.736 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tong, T.; Wang, X.; Zhai, F.; Li, X. The Effect of the KDL Active School Plan on Children and Adolescents’ Physical Fitness in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13286. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013286

Tong T, Wang X, Zhai F, Li X. The Effect of the KDL Active School Plan on Children and Adolescents’ Physical Fitness in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(20):13286. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013286

Chicago/Turabian StyleTong, Tiantian, Xiaozan Wang, Feng Zhai, and Xingying Li. 2022. "The Effect of the KDL Active School Plan on Children and Adolescents’ Physical Fitness in China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 20: 13286. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013286

APA StyleTong, T., Wang, X., Zhai, F., & Li, X. (2022). The Effect of the KDL Active School Plan on Children and Adolescents’ Physical Fitness in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13286. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013286