The Physical and Mental Well-Being of Medical Doctors in the Silesian Voivodeship

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characteristics of the Study Group

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Research Tool

2.4. Statistical Analyses

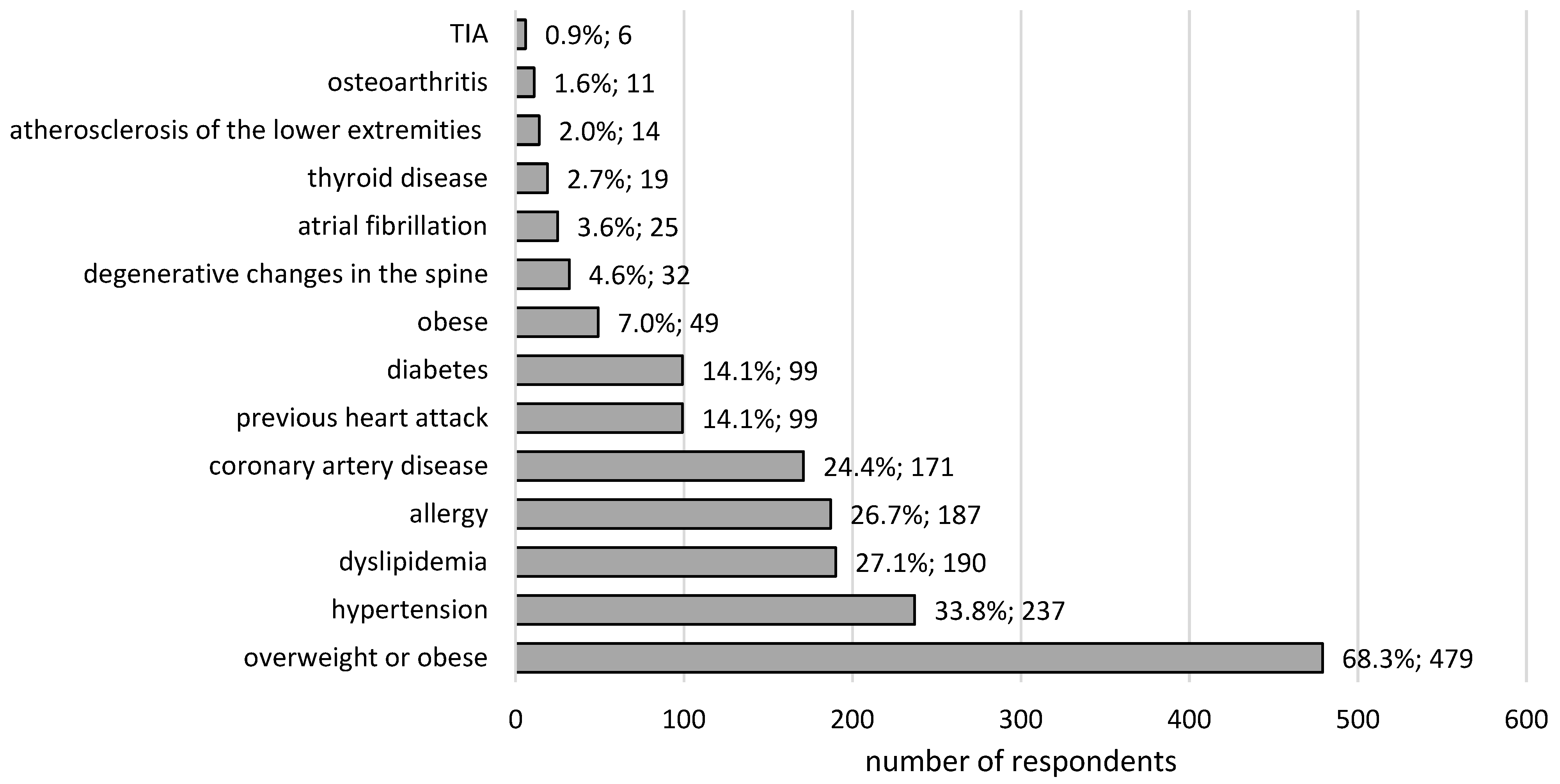

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Świątkowska, B.; Hanke, W. Occupational diseases among health care and social welfare workers in 2009–2016 (In Polish: Choroby zawodowe wśród pracowników opieki zdrowotnej i pomocy społecznej w latach 2009–2016). Medycyna Pracy 2018, 69, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Central Register of Doctors. Statistical Information. Available online: https://nil.org.pl/uploaded_files/1641220880_za-grudzien-2021-zestawienie-nr-03.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2021).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Occupational Hazards in the Health Sector. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/occupational-hazards-in-health-sector (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Kulik, M.M. A suffering that is beyond. On the burnout of doctors working with chronically ill people (In Polish: Cierpienie, które przerasta. Czyli o wypaleniu lekarzy pracujących z ludźmi przewlekle chorymi). Stud. z Psychol. w KUL 2008, 15, 81–112. [Google Scholar]

- Pawełczak, E.; Gaszyński, T. Stressful situations in the profession of an anaesthesiologist and anaesthesiological nurse (In Polish: Sytuacje stresogenne w zawodzie lekarza anestezjologa i pielęgniarki anestezjologicznej). Anestezjol. i Ratow. 2013, 7, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Szemik, S.; Gajda, M.; Kowalska, M. The review of prospective studies on mental health and the quality of life of physicians and medical students (In Polish: Przegląd badań prospektywnych na temat stanu zdrowia psychicznego oraz jakości życia lekarzy i studentów medycyny). Med. Pracy 2020, 71, 483–491. [Google Scholar]

- Mata, D.A.; Ramos, M.A.; Bansal, N.; Khan, R.; Guille, C.; Di Angelantonio, E.; Sen, S. Prevalence of Depression and Depressive Symptoms Among Resident Physicians: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA 2015, 314, 2373–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wójcik, J. Doctor: Profession or Vocation? Doctors’ Attitudes towards Professional Work (In Polish: Lekarz: Zawód czy Powołanie? Postawy Lekarzy Wobec Pracy Zawodowej); Oficyna Wydawnicza Wacław Walasek: Katowice, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Healthcare Workers: Work Stress & Mental Health. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/healthcare/workstress.html (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- De Hert, S. Burnout in Healthcare Workers: Prevalence, Impact and Preventative Strategies. Local Reg. Anesth. 2020, 13, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medscape National Physician Burnout & Suicide Report 2020. Available online: https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2020-lifestyle-burnout-6012460 (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Baliński, P.; Krajewski, R. Doctors and Dentists in Poland—Demographic Characteristics; Supreme Medical Chamber: Warsaw, Poland, 2018; Available online: https://nil.org.pl/uploaded_images/1575630206_demografia-2017.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2021).

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juczyński, Z. Measurement Tools in Health Promotion and Psychology. SWLS—Life Satisfaction Scale (In Polish: Narzędzia Pomiaru w Promocji i Psychologii Zdrowia. SWLS—Skala Satysfakcji z Życia); Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych Polskiego Towarzystwa Psychologicznego: Warszawa, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Peña-Sánchez, J.N.; Domagała, A.; Dubas-Jakóbczyk, K.; Polak, M. A Multidimensional Questionnaire to Measure Career Satisfaction of Physicians: Validation of the Polish Version of the 4CornerSAT. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohanty, A.; Kabi, A.; Mohanty, A.P. Health problems in healthcare workers: A review. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 2568–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Central Statistical Office. Health of the Polish Population in 2019. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/zdrowie/zdrowie/stan-zdrowia-ludnosci-polski-w-2019-r-,26,1.html (accessed on 17 May 2021).

- Sobrino, J.; Domenech, M.; Camafort, M.; Vinyoles, E.; Coca, A. ESTHEN group investigators. Prevalence of masked hypertension and associated factors in normotensive healthcare workers. Blood Press Monit. 2013, 18, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Żołnierczyk-Zreda, D. Long-Term Work and Mental Health and Quality of Life—A Research Review; Central Institute for Labor Protection—National Research Institute: Warszawa, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Han, X.; Zhang, T.; Qu, J. Factors associated with the actual behaviour and intention of rating physicians on physician rating websites: Cross-sectional study. J Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e14417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipka, A.; Janiszewski, M.; Musiałek, M.; Dłużniewski, M. Medical students and a healthy lifestyle (In Polish: Studenci medycyny a zdrowy styl życia). Pedagog. Społeczna 2015, 2, 189–203. [Google Scholar]

- Parużyńska, K.; Nowomiejski, J.; Rasińska, R. Analysis of the phenomenon of occupational burnout of medical personnel (In Polish: Analiza zjawiska wypalenia zawodowego personelu medycznego). Pielęgniarstwo Pol. 2015, 2, 175–180. [Google Scholar]

- Solecki, L.; Klepacka, P. Causes and factors influencing the occurrence of burnout syndrome among physicians employed in public health care sectors (In Polish: Przyczyny oraz czynniki sprzyjające występowaniu zespołu wypalenia zawodowego wśród lekarzy zatrudnionych w publicznych sektorach opieki zdrowotnej). Environ. Med. 2017, 20, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowski, T.M. Positive and negative health consequences of working as a doctor working more than one job (In Polish: Pozytywne i negatywne następstwa zdrowotne pracy lekarza na więcej niż jednym etacie). Pol. Forum Psychol. 2009, 14, 78–89. [Google Scholar]

- Ruscio, A.M.; Hallion, L.S.; Lim, C.C.W.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Al-Hamzawi, A.; Alonso, J.; Andrade, L.H.; Borges, G.; Bromet, E.J.; Bunting, B.; et al. Cross-sectional Comparison of the Epidemiology of DSM-5 Generalized Anxiety Disorder Across the Globe. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yañez, A.M.; Bennasar-Veny, M.; Leiva, A.; García-Toro, M. Implications of personality and parental education on healthy lifestyles among adolescents. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tait, D.; Shanafelt, M.D.; John, H. Noseworthy, Executive Leadership and Physician Well-being: Nine Organizational Strategies to Promote Engagement and Reduce Burnout. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017, 92, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doornenbal, B.M. Big Five personality as a predictor of health: Shortening the questionnaire through the elastic net. Curr. Issues Personal. Psychol. 2021, 9, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güler, Y.; Şengül, S.; Çaliş, H.; Karabulut, Z. Burnout syndrome should not be underestimated. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2019, 65, 1356–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-Calderón, J.; Alonso-Molero, J.; Dierssen-Sotos, T.; Gómez-Acebo, I.; Llorca, J. Burnout syndrome in Spanish medical students. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, H.; Cobucci, R.; Oliveira, A.; Cabral, J.V.; Medeiros, L.; Gurgel, K.; Souza, T.; Gonçalves, A.K. Burnout syndrome among medical residents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Raising Awareness of Stress at Work in Developing Countries. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/924159165X (accessed on 1 October 2022).

| Health Care | Total N = 701 (100%) | 25–50 N = 492 (100%) | 50–80 N = 209 (100%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GP control visits n (%) | no | 52 (7.4) | 35 (7.1) | 17 (8.1) | <0.001 |

| I do not remember | 419 (59.8) | 316 (64.2) | 103 (49.3) | ||

| yes | 230 (32.8) | 141 (28.7) | 89 (42.6) | ||

| GP doctor—last visit (years) | X ± S M (IQR) | 2.3 ± 1.8 2.0 (2.0) | 2.6 ± 2.0 2.0 (2.0) | 1.9 ± 1.5 1.0 (1.0) | <0.01 |

| Specialist control visits n (%) | never | 315 (44.9) | 285 (58.0) | 30 (14.3) | <0.0001 |

| I do not remember | 26 (3.7) | 19 (3.9) | 7 (3.4) | ||

| yes | 360 (51.4) | 188 (38.3) | 172 (82.3) | ||

| Specialist—last visit (years) | X ± S M (IQR) | 2.1 ± 1.8 2.0 (1.0) | 2.4 ± 1.9 2.0 (2.0) | 1.8 ± 1.6 1.0 (1.0) | <0.0001 |

| Dentist n (%) | 697 (99.4) | 490 (99.6) | 207 (99.0) | 0.74 | |

| Dentist—last visit (years) | X ± S M (IQR) | 1.8 ± 1.0 2.0 (1.0) | 1.7 ± 0.8 2.0 (1.0) | 2.0 ± 1.3 2.0 (1.0) | 0.04 |

| Gynecologist—Nw = 336/243/93 (100%) n (%) | 323 (96.1) | 231 (95.1) | 92 (98.9) | 0.18 | |

| Gynecologist—last visit (years) | X ± S M (IQR) | 2.1 ± 1.5 2.0 (2.0) | 2.1 ± 1.3 2.0 (2.0) | 2.3 ± 1.8 2.0 (2.0) | 0.68 |

| Urologist—NM = 365/249/115 (100%) n (%) | 63 (17.3) | 22 (8.8) | 41 (35.7) | <0.0001 | |

| Urologist—last visit (years) | X ± S M (IQR) | 2.6 ± 1.7 2.0 (1.0) | 2.4 ± 1.3 2.0 (1.0) | 2.7 ± 1.9 2.0 (1.0) | 0.59 |

| Glasses/lenses n (%) | 498 (71) | 320 (65) | 178 (85.2) | <0.0001 | |

| Blood pressure control n (%) | I do not remember | 16 (2.3) | 14 (2.6) | 2 (1.0) | <0.0001 |

| a few years ago | 8 (1.1) | 7 (1.4) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| 1–2 years ago | 49 (7.0) | 48 (9.8) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| several times a year | 290 (41.4) | 267 (54.3) | 23 (11.0) | ||

| several times a month | 253 (36.1) | 133 (27.2) | 120 (57.4) | ||

| a few times a week | 71 (10.1) | 21 (4.3) | 50 (23.9) | ||

| every day | 14 (2.0) | 2 (0.4) | 12 (5.7) | ||

| Glucose control n (%) | never | 5 (0.7) | 5 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | <0.0001 |

| I do not remember | 18 (2.6) | 15 (3.0) | 3 (1.4) | ||

| a few years ago | 113 (16.1) | 106 (21.5) | 7 (3.3) | ||

| 1–2 years ago | 302 (43.1) | 240 (48.8) | 62 (29.7) | ||

| in the last year | 263 (37.5) | 126 (25.6) | 137 (65.6) | ||

| Lipid control n (%) | never | 16 (2.3) | 15 (3.0) | 1 (0.6) | <0.0001 |

| I do not remember | 26 (3.7) | 23 (4.7) | 3 (1.4) | ||

| a few years ago | 104 (14.8) | 101 (20.5) | 3 (1.4) | ||

| 1–2 years ago | 292 (41.7) | 222 (45.1) | 70 (33.4) | ||

| in the last year | 263 (37.5) | 131 (26.6) | 132 (63.2) | ||

| Densitometry n (%) | 104 (14.8) | 18 (3.7) | 49 (23.4) | <0.0001 | |

| Sick leave n (%) | 596 (85.0) | 394 (80.1) | 202 (96.7) | <0.0001 | |

| Sick leave (number of days in the year) | X ± S M (IQR) | 16.7 ± 24.1 10.0 (10.0) | 13.0 ± 20.4 7.0 (9.0) | 23.9 ± 28.7 14.0 (20.0) | <0.0001 |

| Sick leave—term n (%) | never | 104 (14.8) | 97 (19.8) | 7 (3.3) | <0.0001 |

| over 5 years ago | 98 (14.0) | 69 (14.1) | 29 (13.9) | ||

| 3–5 years ago | 152 (21.7) | 121 (24.6) | 31 (14.8) | ||

| 1–2 years ago | 195 (27.8) | 135 (27.5) | 60 (28.7) | ||

| in the last year | 151 (21.5) | 69 (14.1) | 82 (39.2) | ||

| Anthropometric Data/ Social/ Economic: Reference Group | HADS-A | HADS-D | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 25–50 | 50–80 | Total | 25–50 | 50–80 | ||||||||

| OR [95% CI] | p-Value | OR [95% CI] | p-Value | OR [95% CI] | p-Value | OR [95% CI] | p-Value | OR [95% CI] | p-Value | OR [95% CI] | p-Value | ||

| Age: 25–50 years old | 50–80 age group | 4.98 [3.47–7.16] | <0.0001 | - | - | - | - | 6.32 [4.22–9.47] | <0.0001 | - | - | - | - |

| Sex: women | men | 0.76 [0.54–1.07] | 0.11 | 0.54 [0.33–0.89] | 0.02 | 0.88 [0.51–1.52] | 0.65 | 1.38 [0.94–2.02] | 0.10 | 1.02 [0.56–1.84] | 0.95 | 1.66 [0.95–2.91] | 0.08 |

| BMI: norm | underweight | 1.10 [0.12–10.11] | 0.93 | 1.90 [0.20–17.86] | 0.57 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| overweight | 1.68 [1.13–2.52] | 0.01 | 1.63 [0.95–2.83] | 0.08 | 0.74 [0.36–1.56] | 0.44 | 2.63 [1.59–4.36] | <0.001 | 3.74 [1.63–8.58] | <0.01 | 0.98 [0.46–2.08] | 0.95 | |

| obesity | 3.30 [1.70–6.40] | <0.001 | 3.56 [1.30–9.72] | 0.01 | 0.91 [0.33–2.48] | 0.85 | 5.88 [2.83–12.20] | <0.0001 | 7.31 [2.09–25.54] | <0.01 | 1.62 [0.59–4.45] | 0.35 | |

| Family status: free status | in relation with partner | 0.69 [0.29–1.66] | 0.41 | 0.72 [0.28–1.85] | 0.08 | 0.22 [0.02–2.97] | 0.26 | 1.97 [0.77–5.04] | 0.16 | 2.49 [0.89–7.01] | 0.08 | 0.22 [0.02–2.97] | 0.26 |

| married | 2.64 [1.66–4.20] | <0.0001 | 1.48 [0.86–2.56] | 0.59 | 1.25 [0.27–5.77] | 0.78 | 4.57 [2.43–8.60] | <0.0001 | 2.76 [1.27–6.01] | 0.01 | 0.88 [0.19–4.09] | 0.87 | |

| divorced | 4.34 [2.17–8.70] | <0.0001 | 2.93 [1.15–7.47] | 0.02 | 1.58 [0.29–8.61] | 0.60 | 6.32 [2.73–14.66] | <0.0001 | 4.58 [1.40–14.94] | 0.01 | 0.95 [0.17–5.23] | 0.96 | |

| widowed | 9.43 [3.36–26.45] | <0.0001 | - | - | 2.10 [0.36–12.32] | 0.41 | 23.18 [7.61–70.58] | <0.0001 | - | - | 2.10 [0.36–12.32] | 0.41 | |

| Children: no | yes | 1.83 [0.82–4.09] | 0.14 | 1.88 [1.14–3.11] | 0.01 | 0.82 [0.29–2.36] | 0.72 | 4.02 [2.43–6.66] | <0.0001 | 2.86 [1.48–5.54] | <0.01 | 0.79 [0.27–2.25] | 0.65 |

| Partner working in the medical profession: no | yes | 1.22 [0.82–1.81] | 0.33 | 1.15 [0.63–2.10] | 0.65 | 1.20 [0.67–2.16] | 0.54 | 1.19 [0.78–1.82] | 0.43 | 1.31 [0.66–2.62] | 0.44 | 1.03 [0.56–1.86] | 0.93 |

| Subjective assessment of economic status: bad | medium | 0.58 [0.29–1.16] | 0.12 | 0.45 [0.19–1.04] | 0.06 | 0.20 [0.02–1.69] | 0.14 | 0.69 [0.33–1.44] | 0.32 | 0.50 [0.19–1.3] | 0.16 | 0.35 [0.07–1.88] | 0.22 |

| good | 0.28 [0.12–0.64] | <0.01 | 0.29 [0.10–0.84] | 0.02 | 0.05 [0.01–0.50] | 0.01 | 0.24 [0.09–0.62] | <0.01 | 0.11 [0.02–0.60] | 0.01 | 0.10 [0.02–0.60] | 0.01 | |

| no opinion | 0.34 [0.14–0.80] | 0.01 | 0.41 [0.15–1.14] | 0.09 | 0.22 [0.02–2.97] | 0.26 | 0.26 [0.10–0.72] | 0.01 | 0.36 [0.11–1.22] | 0.10 | 0.16 [0.02–1.63] | 0.12 | |

| Place of residence: flat | house | 2.64 [1.86–3.74] | <0.0001 | 1.20 [0.66–2.16] | 0.55 | 1.37 [0.75–2.53] | 0.31 | 3.53 [2.40–5.21] | <0.0001 | 1.81 [0.93–3.53] | 0.08 | 1.48 [0.79–2.77] | 0.23 |

| Credit obligations: no | yes | 0.91 [0.65–1.27] | 0.58 | 1.10 [0.68–1.79] | 0.69 | 0.77 [0.45–1.33] | 0.35 | 0.73 [0.50–1.07] | 0.11 | 0.93 [0.51–1.68] | 0.81 | 0.61 [0.35–1.07] | 0.09 |

| Professional Environment: Reference Group | HADS-A | HADS-D | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 25–50 | 50–80 | Total | 25–50 | 50–80 | ||||||||

| OR [95% CI] | p-Value | OR [95% CI] | p-Value | OR [95% CI] | p-Value | OR [95% CI] | p-Value | OR [95% CI] | p-Value | OR [95% CI] | p-Value | ||

| Primary specialization: no | yes | 3.82 [1.95–7.51] | <0.0001 | 2.06 [1.02–4.16] | 0.04 | - | - | 9.67 [3.02–30.99] | <0.0001 | 4.59 [1.40–15.06] | 0.01 | - | - |

| Additional specialization: no | yes | 1.65 [1.11–2.47] | 0.01 | 1.36 [0.69–2.70] | 0.38 | 0.78 [0.44–1.36] | 0.38 | 1.65 [1.07–2.56] | 0.02 | 2.02 [0.95–4.29] | 0.07 | 0.59 [0.33–1.06] | 0.08 |

| Academic degree: no | yes | 1.20 [0.83–1.75] | 0.33 | 1.98 [1.21–3.25] | 0.01 | 1.06 [0.52–2.14] | 0.87 | 1.06 [0.69–1.61] | 0.80 | 2.05 [1.13–3.73] | 0.02 | 0.92 [0.45–1.88] | 0.82 |

| Hospital: no | yes | 0.28 [0.19–0.40] | <0.0001 | 0.46 [0.24–0.86] | 0.02 | 0.52 [0.30–0.91] | 0.02 | 0.23 [0.15–0.34] | <0.0001 | 0.32 [0.16–0.65] | <0.01 | 0.53 [0.30–0.93] | 0.03 |

| GP clinic: no | yes | 1.07 [0.71–1.61] | 0.75 | 0.86 [0.50–1.48] | 0.59 | 0.82 [0.38–1.73] | 0.60 | 1.26 [0.79–2.02] | 0.33 | 0.94 [0.48–1.83] | 0.85 | 1.03 [0.48–2.21] | 0.95 |

| Having a specialized clinic: no | yes | 2.48 [1.75–3.51] | <0.0001 | 2.18 [1.34–3.54] | 0.002 | 1.08 [0.60–1.96] | 0.79 | 2.85 [1.92–4.23] | <0.0001 | 2.76 [1.51–5.03] | <0.001 | 1.10 [0.60–2.02] | 0.75 |

| Work period (years) | 1.08 [1.07–1.10] | <0.0001 | 1.10 [1.06–1.14] | <0.0001 | 1.06 [1.01–1.11] | 0.01 | 1.09 [1.07–1.11] | <0.0001 | 1.14 [1.09–1.20] | <0.0001 | 1.04 [1.00–1.09] | 0.06 | |

| Number of working hours (hour/week) | 0.98 [0.96–0.99] | <0.01 | 0.99 [0.97–1.02] | 0.54 | 0.99 [0.97–1.00] | 0.14 | 0.98 [0.96–0.99] | <0.01 | 1.00 [0.96–1.03] | 0.78 | 0.99 [0.97–1.00] | 0.12 | |

| Post-shift time at the primary workplace: resting | working | 0.99 [0.66–1.47] | 0.95 | 1.28 [0.77–2.13] | 0.34 | 0.44 [0.21–0.91] | 0.03 | 0.82 [0.52–1.30] | 0.41 | 0.99 [0.53–1.86] | 0.98 | 0.45 [0.22–0.96] | 0.04 |

| Place of rest: in the country | abroad | 0.35 [0.17–0.75] | 0.01 | 0.55 [0.20–1.52] | 0.25 | 0.24 [0.07–0.77] | 0.02 | 0.35 [0.15–0.81] | 0.01 | 0.49 [0.14–1.70] | 0.26 | 2.56 [1.34–4.87] | <0.01 |

| in the country and abroad | 0.35 [0.24–0.50] | <0.0001 | 0.44 [0.26–0.73] | <0.01 | 0.53 [0.29–0.98] | 0.04 | 0.25 [0.17–0.39] | <0.0001 | 0.33 [0.18–0.62] | <0.001 | 0.79 [0.23–2.73] | 0.71 | |

| Annual sick leave (days) | 0.95 [0.91–1.00] | 0.03 | 0.93 [0.88–1.00] | 0.04 | 1.00 [0.94–1.06] | 0.99 | 0.96 [0.92–1.01] | 0.10 | 0.94 [0.87–1.02] | 0.14 | 1.00 [0.94–1.07] | 0.92 | |

| Leisure trips (N/year) | 0.99 [0.91–1.08] | 0.85 | 1.08 [0.96–1.21] | 0.19 | 0.64 [0.48–0.85] | <0.01 | 0.56 [0.45–0.71] | <0.0001 | 0.70 [0.5–0.99] | 0.04 | 0.61 [0.45–0.83] | <0.01 | |

| Professional satisfaction (points) | 0.94 [0.92–0.96] | <0.0001 | 0.95 [0.92–0.98] | <0.001 | 0.94 [0.91–0.97] | <0.001 | 0.93 [0.91–0.95] | <0.0001 | 0.94 [0.91–0.97] | <0.001 | 0.93 [0.89–0.96] | <0.0001 | |

| Health/ Lifestyle: Reference Group | HADS-A | HADS-D | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 25–50 | 50–80 | Total | 25–50 | 50–80 | ||||||||

| OR [95% CI] | p-Value | OR [95% CI] | p-Value | OR [95% CI] | p-Value | OR [95% CI] | p-Value | OR [95% CI] | p-Value | OR [95% CI] | p-Value | ||

| Chronic disease: no | yes | 5.80 [3.46–9.73] | <0.0001 | 3.14 [1.77–5.55] | <0.0001 | 12.76 [1.63–100.01] | 0.02 | 7.43 [3.82–14.46] | <0.0001 | 3.62 [1.72–7.65] | <0.001 | 9.19 [1.17–72.06] | 0.03 |

| Pharmacotherapy: no | yes | 5.26 [3.23–8.57] | <0.0001 | 3.05 [1.74–5.35] | <0.0001 | 5.5 [1.54–19.62] | <0.01 | 7.28 [3.84–13.80] | <0.0001 | 4.4 [2.02–9.62] | <0.001 | 3.92 [1.10–13.98] | 0.04 |

| Sick leave (days/year) | 1.01 [1.00–1.01] | 0.09 | 1.00 [0.99–1.01] | 0.84 | 1.00 [0.99–1.01] | 0.84 | 1.01 [1.00–1.01] | 0.06 | 1.00 [0.99–1.02] | 0.98 | 1.00 [0.99–1.01] | 0.84 | |

| Physical activity: irregular | frequent | 0.19 [0.07–0.53] | <0.01 | 0.32 [0.10–1.06] | 0.06 | 0.07 [0.01–0.53] | 0.01 | 0.14 [0.03–0.58] | 0.01 | 0.18 [0.02–1.32] | 0.09 | 0.10 [0.01–0.82] | 0.03 |

| Diet: never | yes whenever | 3.33 [2.33–4.77] | <0.0001 | 1.95 [1.12–3.36] | 0.02 | 2.71 [1.55–4.74] | <0.001 | 4.41 [2.98–6.54] | <0.0001 | 3.06 [1.64–5.72] | <0.001 | 2.82 [1.59–4.99] | <0.001 |

| Alcohol: no | yes | 0.78 [0.55–1.09] | 0.15 | 0.58 [0.36–0.94] | 0.03 | 1.07 [0.62–1.84] | 0.81 | 0.99 [0.68–1.44] | 0.94 | 0.86 [0.47–1.55] | 0.61 | 1.13 [0.65–1.96] | 0.67 |

| Chronic fatigue: no | yes | 7.98 [5.47–11.64] | <0.0001 | 6.27 [3.75–10.48] | <0.0001 | 5.23 [2.81–9.73] | <0.0001 | 5.93 [3.95–8.92] | <0.0001 | 2.86 [1.55–5.27] | <0.001 | 5.30 [2.74–10.26] | <0.0001 |

| Sleep (hours) | 0.71 [0.56–0.90] | <0.01 | 0.68 [0.48–0.97] | 0.03 | 1.16 [0.81–1.68] | 0.42 | 0.74 [0.57–0.96] | 0.02 | 0.74 [0.48–1.14] | 0.18 | 1.16 [0.80–1.68] | 0.44 | |

| Smoking: no | yes | 1.26 [0.82–1.93] | 0.29 | 1.30 [0.72–2.35] | 0.39 | 1.39 [0.67–2.86] | 0.37 | 1.50 [0.95–2.37] | 0.08 | 1.96 [1.01–3.83] | 0.05 | 1.35 [0.66–2.78] | 0.42 |

| Packet Years of Smoking | 1.04 [1.01–1.08] | 0.01 | 1.03 [0.97–1.09] | 0.30 | 1.01 [0.96–1.06] | 0.82 | 1.03 [0.99–1.06] | 0.12 | 1.04 [0.98–1.10] | 0.19 | 0.96 [0.91–1.02] | 0.17 | |

| Life satisfaction (points) | 0.77 [0.73–0.82] | <0.0001 | 0.76 [0.70–0.83] | <0.0001 | 0.80 [0.74–0.87] | <0.0001 | 0.81 [0.77–0.86] | <0.0001 | 0.84 [0.77–0.91] | <0.0001 | 0.83 [0.76–0.89] | <0.0001 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Niewiadomska, E.; Łabuz-Roszak, B.; Pawłowski, P.; Wypych-Ślusarska, A. The Physical and Mental Well-Being of Medical Doctors in the Silesian Voivodeship. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13410. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013410

Niewiadomska E, Łabuz-Roszak B, Pawłowski P, Wypych-Ślusarska A. The Physical and Mental Well-Being of Medical Doctors in the Silesian Voivodeship. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(20):13410. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013410

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiewiadomska, Ewa, Beata Łabuz-Roszak, Piotr Pawłowski, and Agata Wypych-Ślusarska. 2022. "The Physical and Mental Well-Being of Medical Doctors in the Silesian Voivodeship" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 20: 13410. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013410

APA StyleNiewiadomska, E., Łabuz-Roszak, B., Pawłowski, P., & Wypych-Ślusarska, A. (2022). The Physical and Mental Well-Being of Medical Doctors in the Silesian Voivodeship. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13410. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013410