Understanding How Marine Protected Areas Influence Local Prosperity—A Case Study of Gili Matra, Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

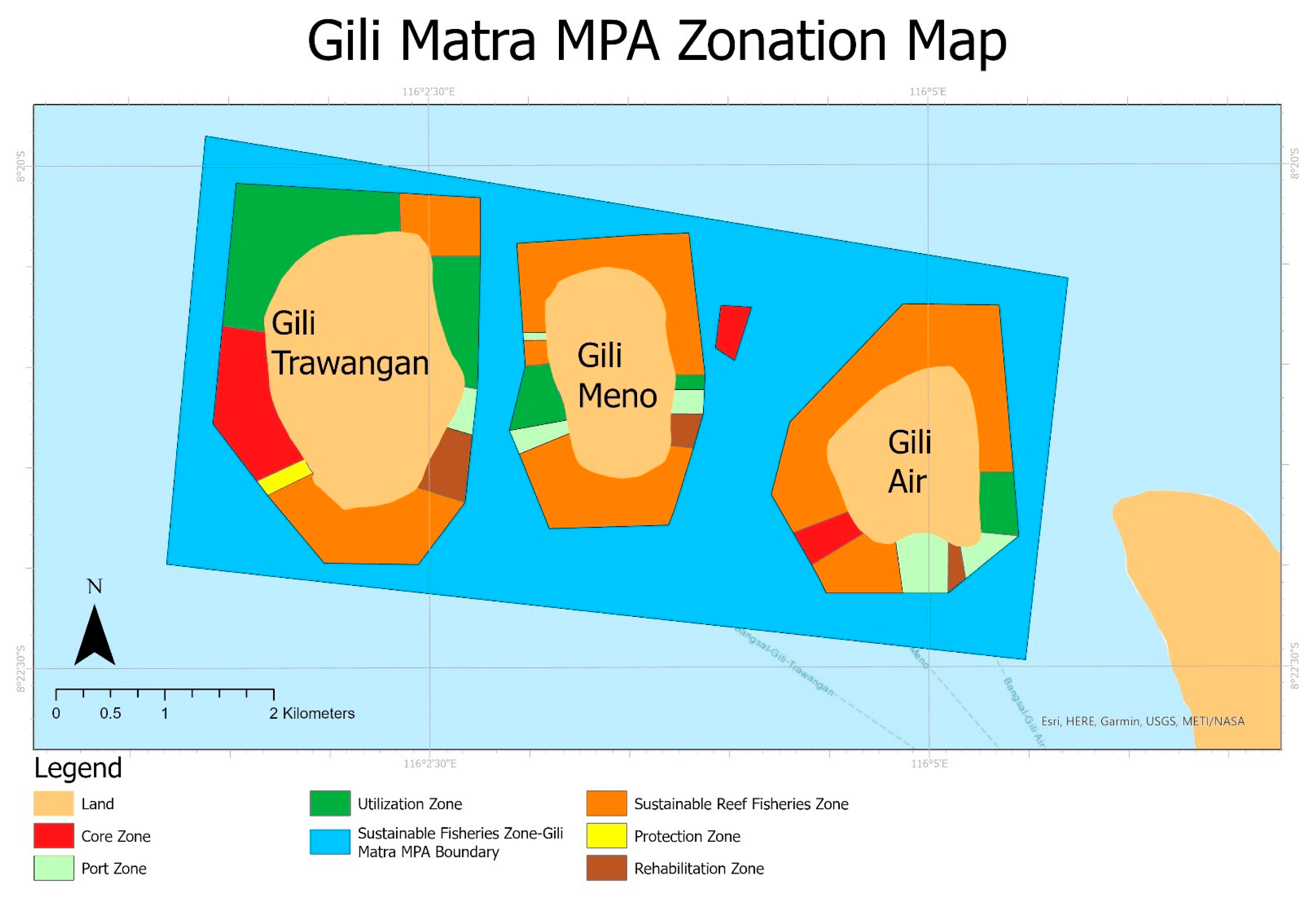

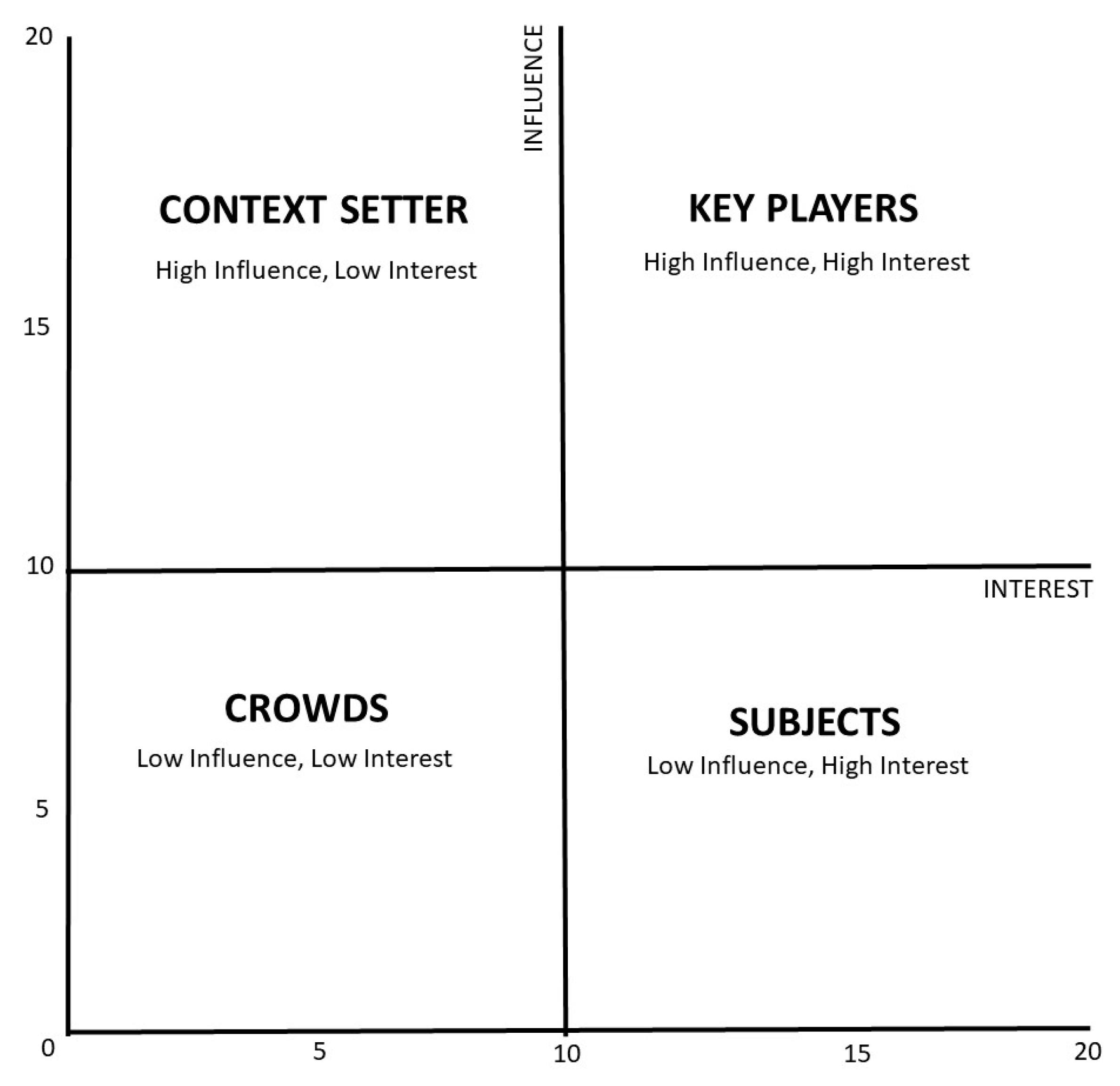

2.1. Stakeholder Identification and Mapping

2.2. Current Conditions and Mental Model

3. Results

3.1. Stakeholder Mental Model on the MPA Influencing Local Prosperity

3.1.1. Opportunity Mental Model of Influential Stakeholders

Gili Matra has been well known for its mass tourism since around 1990; the tourism has caused the community to live much more prosperously. This is the main source of prosperity in the area.(IS 1, 2022)

Gili Matra is one of the world-class tourism destinations. Its potency has led to it being included as one of the national strategic tourism areas. This makes Gili Matra one of the largest contributors for district revenue.(IS 3, 2022)

The prosperity in the MPA could be achieved on the basis of the livelihood formed from the marine tourism; there is a wide range of jobs and economic activity derived from the tourism in the form of guides, accommodation, catering, attraction, and transport.(IS 2, 2022)

The responsibility for establishing proper infrastructure for education belongs to the district government, not the MPA.(IS 2, 2022)

Even until recently, the education infrastructure in Gili Matra has been limited. However, the money from tourism enables them to send their kids to better schools in the mainland; some are even able to pay for education abroad.(IS 3, 2022)

However, although the massive tourism in Gili Matra enables the people to afford an education, it is worrying to see that some of them are not willing to continue their school due to their ability to earn money in the tourism business without a school degree. This issue may be unrelated to the MPA, but it will be much better if the MPA can regulate something to solve this issue.(IS 4, 2022)

3.1.2. Security Mental Model of Influential Stakeholders

Involving the community is essential to ensuring the effectiveness of MPA management. Allowing the community to participate in the management approach could be carried out through encouraging the establishment of thematic community groups, such as the sustainable tourism group, aquaculture group, fisher group, and fish processing group, and through providing them channels to government grants. The mentioned scheme could encourage people to strengthen their organizing skills for social life.(IS 1, 2022)

The crisis resiliency of the Gili Matra people could be high, but it depends on the type of crisis. Reflecting on the massive earthquake in 2018, the people in Gili Matra only needed two months to recover and had the tourism activities back to normal. I conclude that the years of experience in managing tourism have caused the people in Gili Matra to adapt, survive, and work together in recovering Gili Matra whenever crises arise.(IS 3, 2022)

The massive tourism activity in MPA triggers the private sector to invest in health infrastructure in Gili Matra. The MPA may also have contributed to some public health facilities, but it is not significant.(IS 2, 2022)

Since the tourism in Gili Matra proliferated, the private investor’s health facility has grown. Some health facilities from the state are also available. Additionally, Gili Matra also has better sanitation by installing wastewater treatment facilities in multiple sites within the area.(IS 4, 2022)

I am seeing that the MPA in Gili Matra is a government approach to preserving the coral reefs and other marine ecosystems through controlling the utilization of the natural resources.(IS 4, 2022)

The conservation approach in Gili Matra is essential to sustaining tourism. We believe that, without proper control, the ecosystem in Gili Matra will be damaged and no longer support tourism. The people will therefore suffer because they lost their job and their prosperity plummeted.(IS 3, 2022)

From the tourism activities in Gili Matra, numerous economic activities occur from the accommodation, transportation, catering, and guiding, which create livelihood variability. This is the point where the prosperity of the people could arise. However, people have to realize that the actual attraction of Gili Matra is the beauty of the marine ecosystems. Therefore, it is fundamental to preserve the ecosystem to sustain tourism so that the people can prosper.(IS 5, 2022)

The main purpose of the MPA is to create the effectiveness of marine resource management, not only for the environment but also for the surrounding people; thus, the communities could receive benefits sustainably, which includes living prosperously.(IS 1, 2022)

Considering that one of the MPA’s aims is to enrich the population of the fish in the ocean, I believe that, in achieving MPA conservation objectives, the prosperity of the communities in Gili Matra will be automatically increased through alternative livelihoods in fisheries.(IS 5, 2022)

3.1.3. Empowerment Mental Model of Influential Stakeholders

Fundamentally, the MPA design process contains public consultation as an important mechanism to finalize the zonation system. Therefore, the MPA will automatically support the public participation in the institutional process.(IS 1, 2022)

Establishing the MPA in Gili Matra is included as a central government approach; therefore, a wide range of community empowerment funding programs should be available.(IS 4, 2022)

The experience and knowledge of the communities about the touristy spots in the area are beneficial to improving the MPA’s tourism. Therefore, by encouraging community groups, the MPA in Gili Matra is obligated to retrieve and consider the people’s data and information for MPA improvement.(IS 2, 2022)

3.2. Mental Model of Non-Influential Stakeholders

The aim of the MPA itself is to create sustainability management of the ocean ecosystem and enable the communities to derive income from it without damaging the marine environment through a zoning system.(NIS 1, 2022)

This MPA in Gili Matra is a government regulation approach to ensure sustainable practice for the utilization of the marine resources by communities; thus, the ecosystem services will remain positive in influencing the community’s social economy in the future.(NIS 2, 2022)

3.2.1. Opportunity Mental Model of Non-Influential Stakeholders

The people in Gili Matra already prospered enough due to their income from the tourism activity, even before the MPA was established. However, uncontrolled tourism also becomes a concern, as it potentially damages natural beauty, especially the coral reefs ecosystem in Gili Matra, and threatens people’s livelihoods. Therefore, we believe that whenever the MPA objectives are achieved, the prosperity of the people will be stable in the future.(NIS 6, 2022)

The education infrastructure in Gili Matra is enough, and the MPA is not responsible for adding more facilities. Therefore, the younger community should pursue higher education on the mainland, and their parents can afford the money from the tourism here.(NIS 4, 2022)

The most directed MPA impact in Gili Matra regarding the education sector is non-formal education regarding marine conservation knowledge. The MPA authority could contribute to improving the capacity of Gili Matra youth’s through the special session in school and spread the essential information about the sustainability of the ocean’s ecosystem.(NIS 11, 2022)

3.2.2. Security Mental Model of Non-Influential Stakeholders

The crisis resiliency of the Gili Matra people can be seen through the earthquake in 2018. Their capacity to manage tourism and their sense of survival united them to recover Gili Matra. Therefore, the tourism activity was restored shortly after the disaster.(NIS 1, 2022)

The health clinic has been growing here since tourism in Gili Matra became very popular, but it is limited to the private clinic, while public health infrastructure is still limited. Considering the MPA status, public health facilities should be more accessible here.(NIS 12, 2022)

If the objective of the MPA in improving the quality of the environment is achieved, the health quality of the people automatically increases. A clean environment is the source of a healthy body.(NIS 2, 2022)

The MPA approach contains several no-take zones that enrich the fish population in Gili Matra’s waters. It is expected that the fish could be one of the ecosystem services to sustain the income of the people in Gili Matra.(NIS 3, 2022)

Gili Matra is blessed with outstanding nature and ecosystem services. During the COVID-19 crisis, we went back to the sea to capture fish to survive. Therefore, conserving the ocean through the MPA is essential for us to live in the future.(NIS 8, 2022)

3.2.3. Empowerment Mental Model of Non-Influential Stakeholders

The MPA mechanism to socialize and spread the essential information of the conservation approach implementation created the opportunity for people here to voice their aspirations. The community also provided their opinions about the zonation design on the MPA. As far as we understand, the mentioned process is called public consultation to improve public participation.(NIS 5, 2022)

Aside from the consultation phase of the zonation system, the MPA also requires the people to establish community groups to receive the training and government grant packages for community development. The circumstances empower the people to unite and collaborate in a semi-formal organizational scheme.(NIS 10, 2022)

However, there are unmatched perspectives between the community practice and the regulation. For example, the community acknowledges the MPA and zonation system, but at the same time, they draw back from the MPA entrance fee regulation, which potentially decreases the tourism enthusiasm in Gili Matra.(NIS 2, 2022)

Although the MPA zonation design is consulted with the public, there are some other regulations that were not approved by the people, such as the MPA entrance fee regulation.(NIS 9, 2022)

In some other areas, the local tradition could strengthen the MPA implementation. Law enforcement and control mechanism value from customary and indigenous knowledge should benefit the MPA to achieve a greater impact and gain people’s trust. Unfortunately, the MPA in Gili Matra does not really apply the value.(NIS 11, 2022)

We understand that the marine ecosystem should be preserved and conserved; thus, the tourism circumstances would remain for decades. However, so far, we have only seen restrictions and higher entrance fees. It makes us wonder whether their objectives are to sustain the ecosystem and the coastal communities’ lives or whether they only want to increase the government income. It seems that the regulation on entrance fees is standardized for all marine national parks in Indonesia, while each marine national park has different characteristics. The current entrance fee regulation cannot be applied in Gili Matra as the low–middle traveler’s tourist characteristic. It is hard to see the direct impact of the entrance fee for Gili Matra. Therefore, instead of following government regulations, we should develop our own initiative to protect Gili Matra’s ecosystem.(NIS 13, 2022)

My concern is when people from the outside, especially the central government, come and try to manage the marine ecosystem here; it does not seem to work. The political situation often creates human resource turnover for the MPA person in charge of Gili Matra. Those circumstances would not achieve strong relationships. Their presence in Gili Matra is still ineffective; we rarely see them here. Therefore, local people in Gili Matra should be more involved in the long term to manage the MPA in Gili Matra instead, as they will provide more presence and control. We also have cultural practices to manage the ocean that are also applicable to MPA implementation.(NIS 7, 2022)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McCleave, J.; Booth, K.; Espiner, S. Love Thy Neighbour? The Relationship Between Kahurangi National Park and the Border Communities of Karamea and Golden Bay, New Zealand. Ann. Leis. Res. 2004, 7, 202–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickland-Munro, J.K.; Allison, H.E.; Moore, S.A. Using resilience concepts to investigate the impacts of protected area tourism on communities. Ann. Tour. Res. 2010, 37, 499–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeman, Y.B.; Yeboah, A.O.; Ashie, E. Protected areas and poverty reduction: The role of ecotourism livelihood in local communities in Ghana. Community Dev. 2019, 50, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakali, S.; Peniston, B.; Basnet, G.; Shrestha, M. Conservation and Prosperity in New Federal Nepal: Opportunities and Challenges; The Asia Foundation: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Day, J.; Dudley, N.; Hockings, M.; Holmes, G.; Laffoley, D.D.A.; Stolton, S.; Wells, S.M. Guidelines for Applying the IUCN Protected Area Management Categories to Marine Protected Areas; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2012; Available online: https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/PAG-019-2nd%20ed.-En.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2021).

- Sanchirico, J.N.; Cochran, K.A.; Emerson, P.M. Marine Protected Areas: Economic and Social Implications; Resources for the Future: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Purwanto; Andradi-Brown, D.A.; Matualage, D.; Rumengan, I.; Awaludinnoer; Pada, D.; Hidayat, N.I.; Amkieltiela; Fox, H.E.; Fox, M.; et al. The Bird’s Head Seascape Marine Protected Area network—Preventing biodiversity and ecosystem service loss amidst rapid change in Papua, Indonesia. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2021, 3, e393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurney, G.G.; Pressey, R.L.; Cinner, J.; Pollnac, R.B.; Campbell, S. Integrated conservation and development: Evaluating a community-based marine protected area project for equality of socioeconomic impacts. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2015, 370, 20140277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Publications. World Development Report 2000-2001: Attacking Poverty, New Edition ed.; World Bank Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Leisher, C.; Carlton, V.A.; Van Beukering, P.; Scherl, L. Nature’s Investment Bank: How Marine Protected Areas Contributed to Poverty Reduction. 2007. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/288676649_Nature’s_investment_bank_Marine_protected_areas_contribute_to_poverty_reduction (accessed on 9 November 2021).

- Brown, K.; Adger, W.; Tompkins, E.; Bacon, P.; Shim, D.; Young, K. Trade-off analysis for marine protected area management. Ecol. Econ. 2001, 37, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, S.E.; Attrill, M.J.; Austen, M.C.; Mangi, S.C.; Rodwell, L.D. A thematic cost-benefit analysis of a marine protected area. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 114, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizrahi, M.; Diedrich, A.; Weeks, R.; Pressey, R.L. A Systematic Review of the Socioeconomic Factors that Influence How Marine Protected Areas Impact on Ecosystems and Livelihoods. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2019, 32, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Beukering, P.J.H.; Scherl, L.M.; Leisher, C. The role of marine protected areas in alleviating poverty in the Asia-Pacific. In Nature’s Wealth: The Economics of Ecosystem Services and Poverty; Papyrakis, E., Bouma, J., van Beukering, P.J.H., Brouwer, R., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013; pp. 115–133. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/natures-wealth/role-of-marine-protected-areas-in-alleviating-poverty-in-the-asiapacific/1FF1F93B5A927CB75DCDB058A1AC7F7E (accessed on 9 November 2021).

- Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries. Rencana Pengelolaan dan Zonasi Taman Wisata Perairan Pulau Gili Ayer, Gili Meno dan Gili Trawangan di Provinsi Nusa Tengara Barat Tahun 2014-2034. In Keputusan Menteri Kelautan dan Perikanan Republik Indonesia No.57/2014; Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kurniawan, F.; Adrianto, L.; Bengen, D.G.; Prasetyo, L.B. Patterns of Landscape Change on Small Islands: A Case of Gili Matra Islands, Marine Tourism Park, Indonesia. Procedia -Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 227, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Murray-Webster, R.; Simon, P. Making sense of stakeholder mapping. PM World Today 2006, 8, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Aligica, P.D. Institutional and Stakeholder Mapping: Frameworks for Policy Analysis and Institutional Change. Public Organ. Rev. 2006, 6, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DE Lopez, T.T. Stakeholder Management for Conservation Projects: A Case Study of Ream National Park, Cambodia 1. Environ. Manag. 2001, 28, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vance-Borland, K.; Holley, J. Conservation stakeholder network mapping, analysis, and weaving. Conserv. Lett. 2011, 4, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, F.; Eden, C. Strategic Management of Stakeholders: Theory and Practice. Long Range Plan. 2011, 44, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golder, B.; Gawler, M. Cross-cutting tool Stakeholder analysis. In Resources for Implementing the WWF Standards; WWF: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Muqorrobin, A.; Yulianda, F.; Taryono, T. Co-management mangrove ecosystem in the Pasarbanggi Village, Rembang District, Central Java. Int. J. Bonorowo Wetl. 2013, 3, 114–131. Available online: https://smujo.id/bw/article/download/2250/2076 (accessed on 9 November 2021).

- Abbas, R. Mekanisme Perencanaan Partisipasi Stakeholder Taman Nasional Gunung Rinjani. 2005. Available online: https://repository.ipb.ac.id/handle/123456789/41590 (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Jones, N.A.; Ross, H.; Lynam, T.; Perez, P. Eliciting Mental Models: A Comparison of Interview Procedures in the Context of Natural Resource Management. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurmond, V.A. The Point of Triangulation. J. Nurs. Sch. 2001, 33, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N.; Ross, H.; Lynam, T.; Perez, P.; Leitch, A. Mental Models: An Interdisciplinary Synthesis of Theory and Methods. Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, K.; Guerrero, A.M.; Adams, V.; Biggs, D.; Blackman, D.A.; Craven, L.; Dickinson, H.; Ross, H. Mental models for conservation research and practice. Conserv. Lett. 2019, 12, e12642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkhata, B.A.; McCool, S.F. Coupling Protected Area Governance and Management through Planning. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2012, 14, 394–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roitman, S. Top-Down and Bottom-Up Strategies for Housing and Poverty Alleviation in Indonesia: The PNPM Programme in Yogyakarta. In Dynamics and Resilience of Informal Areas: International Perspectives; Attia, S., Shabka, S., Shafik, Z., Ibrahim, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawole, R. Analysis and Mapping of Stakeholders in Traditional Use Zone within Marine Protected Area. J. Manaj. Hutan Trop. J. Trop. For. Manag. 2012, 18, 110–117. Available online: https://journal.ipb.ac.id/index.php/jmht/article/view/6043 (accessed on 9 November 2021). [CrossRef]

- Riahi, Y. Project stakeholders: Analysis and management processes. SSRG Int. J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2017, 4, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, M.; Weeks, R.; Pressey, R.L.; Gleason, M.G.; Eisma-Osorio, R.-L.; Lombard, A.T.; Harris, J.M.; Killmer, A.B.; White, A.; Morrison, T. Real-world progress in overcoming the challenges of adaptive spatial planning in marine protected areas. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 181, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleason, M.; McCreary, S.; Miller-Henson, M.; Ugoretz, J.; Fox, E.; Merrifield, M.; McClintock, W.; Serpa, P.; Hoffman, K. Science-based and stakeholder-driven marine protected area network planning: A successful case study from north central California. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2010, 53, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.J. A governance analysis of the Galápagos Marine Reserve. Mar. Policy 2013, 41, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossiter, J.S.; Levine, A. What makes a “successful” marine protected area? The unique context of Hawaii′s fish replenishment areas. Mar. Policy 2014, 44, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E.; Baine, M.; Killmer, A.; Howard, M. Seaflower marine protected area: Governance for sustainable development. Mar. Policy 2013, 41, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarman, E.T.; Carr, M.H. The California Marine Life Protection Act: A balance of top down and bottom up governance in MPA planning. Mar. Policy 2013, 41, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.J.S. Marine protected areas in the UK: Challenges in combining top-down and bottom-up approaches to governance. Environ. Conserv. 2012, 39, 248–258. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/article/marine-protected-areas-in-the-uk-challenges-in-combining-topdown-and-bottomup-approaches-to-governance/28321D18C253B8FCF08A051D12B7A1A7 (accessed on 9 November 2021). [CrossRef]

- Gaymer, C.F.; Stadel, A.V.; Ban, N.C.; Cárcamo, P.F.; Ierna, J.; Lieberknecht, L.M. Merging top-down and bottom-up approaches in marine protected areas planning: Experiences from around the globe. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2014, 24, 128–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solandt, J.-L.; Jones, P.; Duval-Diop, D.; Kleiven, A.R.; Frangoudes, K. Governance challenges in scaling up from individual MPAs to MPA networks. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2014, 24, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Sánchez, R.D.P.; Maldonado, J. Evaluating the role of co-management in improving governance of marine protected areas: An experimental approach in the Colombian Caribbean. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 2557–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, B.F. Institutional criteria for co-management. Mar. Policy 2000, 24, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, R.; Fennell, D.A. Managing protected areas for sustainable tourism: Prospects for adaptive co-management. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, J. Prospects for co-management in Indonesia’s marine protected areas. Mar. Policy 2003, 27, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, E.R.; Civera, C.; Cortese, D.; Fiandrino, S. Strategising stakeholder empowerment for effective co-management within fishery-based commons. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 2631–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satria, A.; Matsuda, Y.; Sano, M. Questioning Community Based Coral Reef Management Systems: Case Study of Awig-Awig in Gili Indah, Indonesia. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2006, 8, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feruzia, S.; Satria, A. Sustainable coastal resource co-management. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 201, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

| Influence Indicators | Interest Indicators |

|---|---|

| Involvement in Policy Establishment | Involvement in Management |

| Resource Capacity | Achieved Benefit |

| Jurisdiction to Manage | Activities |

| Contribution and Participation | Dependence |

| Name of Stakeholder | Description |

|---|---|

| Influential Stakeholders (IS) | |

| MPA Authority of Gili Matra | This is the primary managing institution of the MPA in Gili Matra. They were appointed by the National Government of Indonesia through the Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries |

| Tourism Agency | Responsible for managing tourism activity in the district, including improving the tourism experience quality in the Gili Matra to attract more visitors. |

| Planning Agency | Designing the district plan and monitoring its implementation through policy approaches, including designing a district revenue stream from the Gili Matra MPA. |

| Fisheries Agency | Managing the fishing activity of the local district, including the fisheries activity in the Gili Matra MPA |

| Environmental Agency | Managing the environmental issue of the local district, including the waste management in the Gili Matra MPA |

| Non-Influential Stakeholders (NIS) | |

| Community Surveillance Group | Local community groups voluntarily surveilling the marine area of the Gili Matra MPA for violations of the MPA zonation and other illegal marine extraction activities |

| Gili Shark Conservation | Local NGO focusing on shark conservation in the Gili Matra MPA |

| Yayasan Gili Matra Bersama | Local NGO focusing on marine conservation and sustainable tourism in the Gili Matra MPA |

| Community Ecotourism Group | Local community group focusing on spreading awareness and practicing community-based sustainable tourism in the Gili Matra MPA |

| Local Activist | Representation of a group of people who actively spread awareness of sustainable tourism and marine conservation in the Gili Matra MPA |

| WCS Indonesia | National NGO working on marine conservation. The Gili Matra MPA is one of their site project locations |

| Local Academician | Representation of local researchers and academics who actively conduct a wide range of research and study programs in the Gili Matra MPA |

| Meno Lestari | Local NGO focusing on marine conservation and sustainable tourism in the Gili Matra MPA |

| Village Officials | Government officials responsible for managing the civil administration of the people in the Gili Matra MPA |

| Gili Eco Trust | Local NGO focusing on marine conservation and sustainable tourism in the Gili Matra MPA |

| Gili Hotel Association | Association for hotel managers in the Gili Matra MPA |

| Gili Business Owner Association | Association for tourism venture owners in Gili Matra. Their members comprise hotels, restaurants, trip operators, caterers, and boat and bar owners in the Gili Matra MPA |

| Small Scale Fishermen Group | Local community organization specifically for the fishermen in the Gili Matra MPA |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rosadi, A.; Dargusch, P.; Taryono, T. Understanding How Marine Protected Areas Influence Local Prosperity—A Case Study of Gili Matra, Indonesia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13508. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013508

Rosadi A, Dargusch P, Taryono T. Understanding How Marine Protected Areas Influence Local Prosperity—A Case Study of Gili Matra, Indonesia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(20):13508. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013508

Chicago/Turabian StyleRosadi, Amrullah, Paul Dargusch, and Taryono Taryono. 2022. "Understanding How Marine Protected Areas Influence Local Prosperity—A Case Study of Gili Matra, Indonesia" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 20: 13508. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013508

APA StyleRosadi, A., Dargusch, P., & Taryono, T. (2022). Understanding How Marine Protected Areas Influence Local Prosperity—A Case Study of Gili Matra, Indonesia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13508. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013508