Aspects of Wellbeing for Indigenous Youth in CANZUS Countries: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy

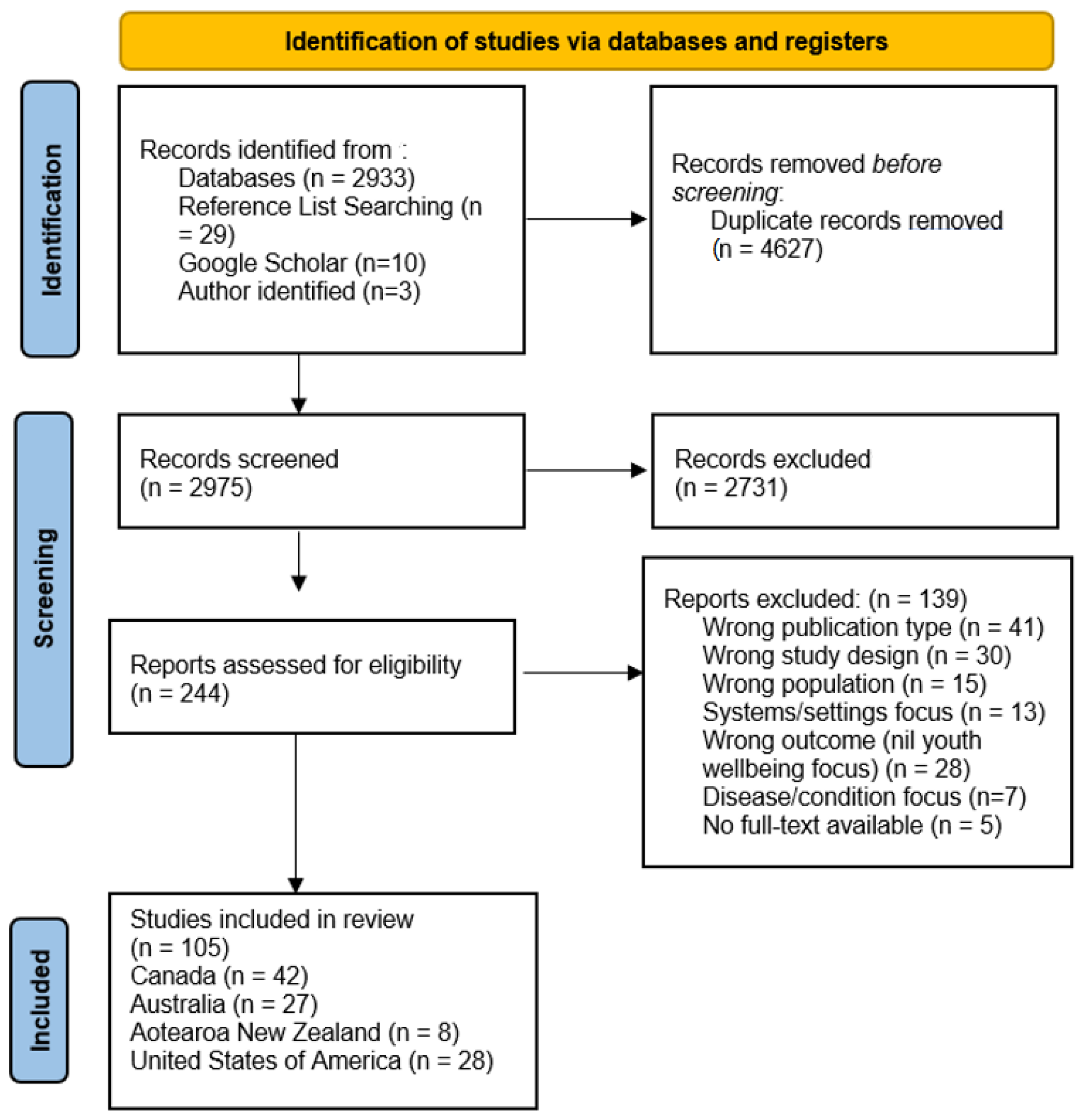

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Paper Characteristics

3.2. Thematic Synthesis

3.2.1. Indigenous Youth in Canada

| Authors (Year) | Region | Study Setting | Indigenous Group | Participant Details | Reporting Person (Youth, Family Proxy, Service Provider Proxy) | Brief Methods | Was Wellbeing Part of Main Aim (YES) or Component of the Broader Research Question (BROAD)? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CANADA | |||||||

| Ansloos et al. (2021) [67] | Vancouver | Community | Indigenous | 8 participants (5 Indigenous participants—analysis only of Indigenous participants) 3F 1M 1Two-Spirit 16–25 years | Youth, retrospective youth | Interviews and observations | BROAD |

| Aylward et al. (2015) [40] | Nunavut | Regional youth program | Nunavut Inuit | 10 Indigenous participants. 5F 5M Alumni who had completed the Northern Youth Abroad Program 2006–2011 | Youth | Semi-structured interviews | BROAD |

| Berman et al. (2009) [41] | South Ontario | Community | NR | 6 Aboriginal participants, out of 19—Aboriginal participant contributions specified All F 14–19 years | Youth | Adapted ethnographic study (field notes and interview style discussion) | BROAD |

| Brown et al. (2012) [42] | Alert Bay | Community | Namgis First nation | Participant details not reported | Youth and Elders | Individual interviews, focus groups | YES |

| Clark et al. (2013) [82] | Kamloops, British Columbia | Community | Melq’ilwiye | 40 Indigenous participants 24F 16M 12–15 years | Youth | Talking circles (40 participants) and surveys | YES |

| Gerlach et al. (2018) [44] | British Columbia | Community services | NR | 35 participants (10 caregivers, 18 workers, 4 Elders, 3 administrative leaders) 30F 2M (excluding administrative leaders) | Indigenous caregivers (mothers, aunties, fathers, Elders) & Aboriginal Infant Development Program workers | In-depth individual and small group interviews | BROAD |

| Hardy et al. (2020) [68] | Toronto | Community | NR | 12 Indigenous participants All self-identified 2SLGBTTQQIA youth | Youth | Focus groups (7 participants) and surveys (5 participants) | BROAD |

| Hatala et al. (2017) [45] Hatala et al. (2019) [77] Hatala et al. (2020) [78] Njeze et al. (2020) [70] | Saskatoon | Community | Plains Cree, Métis Nêhiyaw (Plains Cree), Métis Plains Cree, Métis Nêhiyaw (Cree), Métis, Dene | 28 Indigenous participants 15–25 years 28 Indigenous participants 16F 12M 15–25 years 28 Indigenous participants 16F 12M 16–25 years 6 Indigenous youth (selected from above cohort) 3F 3M | Youth | Photovoice and photo elicitation with open talking circle discussions/ interviews. Four rounds over the course of a year | YES |

| Isaak et al. (2008) [46] | Northern Manitoba | Community | Northern Manitoba First nations | 39 participants (10 adults, 29 children) Children: 13F 16M Children: 12–19 years; Adults: 21–89 years | Youth and proxy reporters (teachers, youth counsellors, community members, Elders, health workers and health board members) | Individual in-depth interviews w/adults; focus groups w/youth | YES |

| Kral (2013) [47] | Igloolik | Community | Inuit | 27 Indigenous participants 11F 15M 17–24 years: 9; 25–44 years: 9; 45+ years: 9 | Youth and proxy community members | Open-ended interviews | YES |

| Kral et al. (2011) [48] | Nunavut | Community | Igloolik, Qikiqtarjuaq | 50 Indigenous participants 25F 25M 14–94 years | Youth and Elders (responses not separated) | Open-ended interviews and surveys | YES |

| Kyoung et al. (2015) [49] | Edmonton | Community | NR | 53 participants (8 Indigenous) 36F 17M 18–51 years | Key informants (44 responsible for care of Aboriginal youths) | Semi-structured interviews, field notes and memos | YES |

| Latimer et al. (2020) [50] | Atlantic region | Community & service delivery | Mi’kmaq, Wolastoq | 220 participants (189 Indigenous community members, 32 professionals in the community; 146 youth participants). Youth: grades 1–12 | Youth, parents and Elders, adult professionals in the community | Semi-structured conversation sessions and interview sessions | BROAD |

| Liebenberg et al. (2022) [79] | Atlantic Canada | Community & service delivery | First Nations | 8 Indigenous participants 14–18 years | Youth | Photovoice, videography, focus group. | YES |

| Lines & Jardine (2019) [51] | Ndilo, Dettah | Community | Yellowknives Dene First Nation | 15 Indigenous participants 13–18 years | Youth and researcher | Photovoice, mural art, sharing circles, observations, field notes, personal reflections | BROAD |

| MacDonald et al. (2015) [52] | Nunatisiavut | Community | Inuit | 17 Indigenous participants 15–25 years | Youth | In-depth, semi-structured interviews | YES |

| McHugh et al. (2014) [53] | Alberta | Community | Métis, First Nation, Aboriginal | 8 Indigenous participants All F 15–18 years | Youth | Semi-structured interviews | BROAD |

| Mikraszewicz & Richmond (2019) [54] | Biigtigong Nishnaabeg | Community | Anishinaabe | 9 Indigenous participants (5 youth, 4 adults) Youth: 14–18 years | Youth, and community adults and Elders | Interviews | BROAD |

| Navia et al. (2018) [55] | Calgary | Community | NR | 20 Indigenous participants 11F 9M 18–29 years | Retrospective youth | Interviews and art methods | BROAD |

| Nightingale & Richmond (2021) [69] Nightingale & Richmond (2022) [80] | Biigtigong & Mountain Lake Camp | Community | Anishinaabe | 15 Indigenous participants (4 Elders/knowledge holders, 6 students, 5 camp staff) 11 Indigenous participants (6 students, 5 camp staff) | Youth, Elders/knowledge holders and community camp staff Youth, camp staff | Flexible interviews In-depth story-based interviews | BROAD |

| Oliver et al. (2020) [56] | Vancouver | Community & service delivery | NR | 13 participants (4 Indigenous participants). 9F 4M | Foster parents (level of experience between <1–>20 years) | Semi-structured interviews | BROAD |

| Pace & Gabel (2018) [57] | St Lewis, Labrador | Community | Southern Inuit | 10 Indigenous participants (5 youth, 5 older) Youth: 2F 3M; Adults: 5F 8–24 years: 5; 50–75 years: 5 | Youth and older community members | Co-design workshops and online survey | BROAD |

| Parlee & O’Neil (2007) [58] | Lutsel K’e | Community | Chipewyan Dene | NR | Community members | Open-ended interviews | YES |

| Quinn (2012) [71] | Ontario | Community | NR | 7 Indigenous participants 4F 3M 27–69 years | Retrospective youth proxy | Semi-structured interviews | BROAD |

| Ritchie et al. (2014) [59] | Ontario | Community | Wikwemikong Unceded Indian Reserve | 43 Indigenous participants 16F 27M 12–19 years | Youth | Journals, interviews, talking circles and Elder teachings | YES |

| Sasakamoose et al. (2016) [60] | Canadian prairies | Community | First Nations and Métis | 13 Indigenous participants 14–17 years | Youth | Sharing circles | YES |

| Shea et al. (2013) [61] | Battleford Tribal Council Region | Community | First Nations and Métis | Participant number NR All F 13–16 years | Youth | Photovoice, individual interviews, sharing circles, surveys | YES |

| Skinner & Masuda (2013) [62] | Winnipeg | Community | NR | 8 Indigenous participants 13–20 years | Youth | Focus groups & rap, dance, poetry, photography, painting, mixed media | BROAD |

| Sloan Morgan, Thomas & McNab-Coombs (2022) [81] | Northern British Columbia | Community | First Nations | 6 Indigenous participants | Youth | Photovoice | BROAD |

| Spiegel et al. (2020) [63] | British Columbia | Community | Tsleil-Waututh Nation | Limited description—a mix of family participants within the community | Youth, Elders and families | PhotoVoice & multiple discussion sessions with photos guiding discussions | BROAD |

| Tang & Jardine (2016) [72] | Northwest Canada | Community | Yellowknives Dene | 30 Indigenous participants (11 community members, 19 children) | Youth, parents and community members | Participatory videos by youth & unstructured interviews (youth). Community focus groups (community members) | BROAD |

| Thompson et al. (2013) [64] | NR | Community | First Nations | 15 Indigenous participants 14F 1M | Grandparents | Interview | YES |

| Victor et al. (2016) [65] | Sasketchewan | School setting | First Nations | 14 participants (most identifying as Cree) Grade 8–11 | Youth | Participatory visual photography; interviews; co-researching | YES |

| Wahi et al. (2020) [73] | Ontario & Alberta | Community | Ermineskin Cree Nation, Louis Bull Cree Nation, Samson Cree Nation, and Montana Cree Nation | 60 Indigenous participants (current caregivers of children < 5 years, community members with Indigenous knowledge and community members providing health services) | Caregivers, Elders and community service providers | Single, face-to-face, one-to-one, in-depth, semi-structured interview | BROAD |

| Walls et al. (2014) [74] | Central Canada | Community | First Nations | 66 Indigenous participants (30 Elders, 12 service providers) 21F 21M | Elders and service providers | Focus groups | BROAD |

| Walsh et al. (2020) [75] | Ontario | Community | Cree | 3 Indigenous participants (involved with the land-based intervention the study was based off) | Service providers | Focus group | BROAD |

| Ward et al. (2021) [76] | Newfoundland & Labrador | Community | Innu | 39 Indigenous participants 17–19 years (focus groups); 70+ years (interviews) | Youth and community members | Interviews and focus groups | YES |

| Yuen et al. (2013) [66] | Sasketchewan | School | Cree, Saulteaux, Dakota, Nakota, and Lakota | 18 participants (not specified as Indigenous) 10F 8M Grade 7/8 | Youth | Collaborative activities—games, arts | BROAD |

| AUSTRALIA | |||||||

| Andersen et al. (2016) [83] | Western Sydney | Community | NR | 38 participants (35 Indigenous) 22F 13M 3NR | Familial and service proxy (staff at Aboriginal medical service) | Focus groups | BROAD |

| Canuto et al. (2019) [84] | Yalata, Coober Pedy, Port Lincoln, Adelaide | Community | Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander | 46 Indigenous participants All M 18+ years | Male parents or caregivers | Yarning circle discussions | BROAD |

| Chamberlain et al. (2021) [85] | Melbourne, Alice Springs, Adelaide | Community | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander | 17 Indigenous participants 15F 2M Mean age 29 years | Parents | Parent interviews and discussion groups | BROAD |

| Chenall & Senior (2009) [86] | Northern Territory | Community, school and clinic | Australian Indigenous | 111 participants (not specified as Indigenous— 21 community-based informants; 22 high school students; 8 young women; 50 other community members; 20 non-Aboriginal community members) 42F 27M 42NR High school students: 13–19 years; other informants: <30–50+ years | Youth, community members, school teachers, clinic staff and council staff. | Discussions and workshops | YES |

| Clark et al. (2010) [82] | Tambellup | Community | Noongar | 37 participants (23 Indigenous) | Aboriginal adults and non-Aboriginal leaders from community | Semi-structured interviews with both groups | BROAD |

| Crowe et al. (2017) [87] | South Coast New South Wales | Community and schools | Australian Indigenous | 40 Indigenous participants 24F 16M 12–15 years | Youth | Interviews and surveys | BROAD |

| Dennison et al. (2014) [88] | Far North Queensland | Prison | Australian Indigenous | 41 Indigenous participants All M 21–50 years | Indigenous fathers | Brief questionnaire and a semi-structured interview | BROAD |

| Gee et al. (2022) [89] | Victoria | Community | Koori | 6 Indigenous participants 5F 1M 35–55 years. | Parents | Semi-structured tool and yarning circles | BROAD |

| Gibson et al. (2020) [90] | Wiradjuri country. | Community | Aboriginal | 16 Indigenous participants | Elders | Yarning circle discussion | BROAD |

| Helmer et al. (2015) [91] | Western Australia, Northern Territory, South Australia | Community | NR | 171 participants (88 Indigenous) 100F 71M 16–25 years | Youth | Group discussions and body mapping | BROAD |

| Johnston et al. (2007) [92] | Maningrida | Community | Maningrida Indigenous Australians | 13 Indigenous participants 11F 2M 22–51 years | Adults in the community | Semi-structured interviews | BROAD |

| Kickett-Tucker (2009) [93] | Perth | Community and schools | Noongar | 154 Indigenous participants (focus groups 120; interviews 34) Focus groups: 60F 60M; interviews: 18F 17M Focus groups: 13–17 years; interviews: 8–12 years | Youth | Focus groups and interviews | BROAD |

| Kiraly et al. (2015) [94] | Melbourne | Community | Indigenous Australian | 430 participants (57 looking after Indigenous children; 15 Indigenous) 53F 2M 50–60 years | Caregivers and foster parents | Survey and focus groups | BROAD |

| Kruske et al. (2012) [95] | Northern Australia | Community | Aboriginal | 15 Indigenous mother and baby pairings, plus associated family. All F Mothers: 15–29 years | Mothers, fathers and family members | Ethnographic; interviews every 4–6 weeks; photographs; field notes; observations | BROAD |

| Lowell et al. (2018) [96] | Northern Territory | Community | Yolŋu | 36 Indigenous participants (30 community members, 6 children) Children: 3F 3M Children: 2mo–2 years; community members: 18–70 years | Family and community; researcher observations | Longitudinal case studies over 5 years with in-depth interviews, video-reflexive ethnography | BROAD |

| McCalman et al. (2020) [97] | Queensland | Boarding Schools | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander | 9 participants (3 Indigenous) 6F 3M | Boarding school staff | Open-ended interview | BROAD |

| Miller et al. (2020) [98] | New South Wales | Community and health services | Aboriginal | 425 participants (321 Indigenous) 383F 42M 18–50+ years | Parents and carers | Survey with open-ended questions | YES |

| Mohajer et al. (2009) [99] | Rural Australia | Community | Aboriginal | 99 Indigenous participants 59F 40M 12–18 years | Youth | Individual interviews and/or focus group discussions | BROAD |

| Murrup-Stewart et al. (2021) [100] | Naarm/ Melbourne | Community | Aboriginal | 20 Indigenous participants 14F 6M 18–27 years | Retrospective youth | One-on-one yarning sessions | YES |

| Povey et al. (2020) [101] | Northern Territory | Community | Aboriginal | 45 Indigenous participants 10–18 years | Youth | Co-design workshops & online survey | YES |

| Priest, Mackean, et al. (2012) [102] Priest, Mackean, et al. (2012) [103] | Melbourne | Community; community-controlled health sector | Aboriginal | 25 participants (not specified Indigenous) 18F 7M | Parents, family members, grandparents; and Aboriginal child or health workers; and foster parents | Interviews | YES |

| Priest et al. (2017) [104] | Melbourne | Community; community-controlled health sector | Koori | 31 Indigenous participants 19F 12M 8–12 years | Youth | Focus groups and in-depth interviews | YES |

| Senior & Chenall (2012) [105] | Northern Territory | Community | Aboriginal | 59 Indigenous participants All F 14–19 years | Youth | Focus groups | BROAD |

| Smith et al. (2020) [106] | Northern Territory | Community | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander | 41 Indigenous participants (39 Yarning sessions; 18 individuals allowed social media access) All M 14–25 years | Youth | Yarning Sessions; Photovoice analysis of Facebook posts | BROAD |

| Williamson et al. (2010) [107] | Sydney | Community | Aboriginal | 47 participants (not specified Indigenous) 30F 17M | Parents and Aboriginal health workers | Semi-structured focus groups and small-group interviews | YES |

| Young et al. (2017) [108] | New South Wales | Community controlled health services | Aboriginal | 36 participants (not specified Indigenous) 24F 12M 18–65+ year | Community members, health service professionals and youth workers | Interviews | YES |

| AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND | |||||||

| Abel et al. (2001) [109] | Auckland | Community health service | Māori | 150 participants (26 Māori; others Tongan, Samoan, Cook islands, Niuean, Pakeha) Māori: 17F 9M Mid-teens to early 40s | Parents or grandparents | Focus groups | BROAD |

| Abel et al. (2015) [110] | Hawkes Bay and Tairawhiti | Community | Māori | 22 Māori participants (12 mothers of Māori infants, and 10 key informants) Mothers: 12F 19–39 years | Mothers | Focus groups | BROAD |

| Adcock et al. (2021) [111] | NR | Hospital | Māori | 28 Māori participants (19 mothers, 5 fathers, 2 NICU peers, 1 aunt, 1 grandmother) 23F 5M | Family proxy | Focused life story interviews | BROAD |

| Beavis et al. (2019) [112] | Wellington | Community | Māori | 18 Māori participants (11 children, 7 adults Tamariki/Rangatahi: 2–18 years; Adults: 22–43 years | Youth, caregivers and researchers | Adapted-ethnographic study | BROAD |

| Carlson et al. (2022) [113] | Tāmaki Makaurau (Auckland) | Community | Māori | 22 Māori participants (total 56 participants) 16–20 years | Youth | Open-ended individual interviews | YES |

| Hamley et al. (2021) [114] | Aotearoa broadly | Community | Māori | 23 Māori Rangatahi (27 other non-Māori participants) 34F 16M 1NR 12–22 years | Youth | Interviews | BROAD |

| Moewaka Barnes et al. (2019) [115] | Auckland | School | Māori | 400 students (not specified Māori) | Youth, key informants | Survey with open-ended questions | BROAD |

| Page & Rona (2021) [116] | Te Ōnewanewa | Community | Māori | Rangatahi participants Other details not reported | Youth | Hui (meeting/gathering) | YES |

| UNITED STATES | |||||||

| Ayunerak et al. (2014) [117] | Southwest Alaska | Community | Yup’ik | 4 Indigenous participants | Community members and Elders | Narrative manuscript | BROAD |

| Bjorum (2014) [118] | Maine | Community | Wabanaki | 11 participants (10 Indigenous) 9F 2M | Community members and child welfare staff | Focus groups; semi-structured, open-ended design | BROAD |

| Burnette & Cannon (2014) [119] | South-eastern USA | Community | South-eastern tribe | 29 Indigenous participants All F 22–74 years | Mothers and female tribe members | Life history interviews; semi-structured | BROAD |

| Cross & Day (2008) [120] | NR | Community | American Indian | 8 youth-grandparent Indigenous dyads Children: 4F 4M; Grandparents: 7F 1M. Children: 11–17 years; Grandparents: 51–72 years. | Youth and grandparents | Individual, in-person interviews | BROAD |

| Dalla et al. (2010) [121] | Navajo reservation | Community | Navajo | 21 Indigenous participants All F 16–37 years | Young mothers and older mothers | Interviews | BROAD |

| de Schweinitz et. al.(2017) [122] | Alaska rural interior | Community | Athabascan | 37 Indigenous participants 28F 9M | Youth and adults in the community | Focus groups | YES |

| DeCou et al. (2013) [123] | Alaska | Community | Alaska Native | 25 Indigenous participants 18F 7M 18–37 years | Retrospective youth | Individual interviews | BROAD |

| Ford et al. (2012) [124] | Southwestern Alaska | Community | Yup’ik | 25 Indigenous participants 11–18 years | Youth | Life history interviews | BROAD |

| Freeman (2019) [125] | Northern USA | Community | Rotinohshonni | 19 Indigenous participants (14 youth, 5 adults) Youth: 11F 3M; Adults: 4F 1M | Youth and adults | Interviews | YES |

| Friesen et al. (2015) [126] | NR | Community | American Indian, Alaska Native | 33 Indigenous participants 21F 12M 17–23 years | Youth and early adults | Interviews and focus groups | BROAD |

| Goodkind et al. (2012) [127] | Southwestern USA | Community reservation | Diné (Navajo) | 37 Indigenous participants (14 youth, 15 parents/guardians, 8 granparents) Youth: 8F 6M; Parents: 12F 3M; Grandparents: 8F Youth: 12–17 years; Parents: 24–49 years; Grandparents: 54–90 years | Youth, parents and grandparents | Individual interviews | YES |

| Hand (2006) [128] | Northern USA | Community | Ojibwe | Poorly described sample—ethnographic interviews of an Ojibwe community | Elders and community members, child welfare personnel | Critical ethnography | BROAD |

| House et al. (2006) [129] | Southwestern USA | Community | Southwestern American Indian | 24 Indigenous participants (10 youth, 6 parents, 9 Elders) 13–90 years | Youth, parents and Elders | Focus groups | BROAD |

| Isaacson et al. (2018) [130] | Northern Plains reservation | Community | Plains tribe | 14 Indigenous participants (8 youth, 6 Elders) Youth: 7F 1M Youth: 13–17 years | Youth and Elders | Talking circles | YES |

| Lewis et al. (2018) [131] | Dillingham | Community | Yup’ik | 20 Indigenous participants 14F 6M 46–95 years | Grandparents | Semi-structured interviews | BROAD |

| McKinley et al. (2020) [132] | South-eastern USA | Community | Indigenous | 436 Indigenous participants across two tribal communities Youth: 11–23 years; Adults: 24–54 years; Elders: 55+ years | Youth and community members | Individual interviews; family interviews; focus groups | YES |

| Nu & Bersamin (2017) [133] | Southwestern Alaska | Community | Yup’ik | Poor description of participants—community based study | Youth and community | Focus groups | BROAD |

| Rasmus et al. (2014) [134] | Bering Sea Coast Alaska | Community | Yup’ik | 25 Indigenous participants 12F 13M 11–18 years | Youth | Interviews; life history & ‘memoing’ of interviews | YES |

| Strickland et al. (2006) [135] | Pacific Northwest | Community | Pacific Northwest Tribe | 49 Indigenous participants (40 parents, 9 Elders) | Parents and Elders | Interviews and focus groups | BROAD |

| Trinidad (2009) [136] | Hawaii | Community | Native Hawaiian | 17 participants (16 Indigenous—8 young adults, 4 youth staff, 2 parents, 2 board members, 1 Elder) 17–25 years youth | Youth, parents, Elders, community advocates | Open-ended interviews | BROAD |

| Trout et al. (2018) [137] | Alaska | Community | Inupiaq | 17 youth researchers (11 Indigenous—10 adults in focus groups, 20 interviews with local researchers 14–25 years youth researchers | Youth, adults and Elders | Q&A sessions, photovoice, digital storytelling, interviews | BROAD |

| West et al. (2012) [138] | Chicago | Community | Chicago American Indian | 107 Indigenous youth and families (15 youth participants) 71F 36M Youth: <18 years | Youth, family members and Elders | Focus groups | BROAD |

| Wexler (2006) [139] Wexler (2009) [140] | Northwest Alaska | Community | Inupiat | 12 focus groups of 3–12 Indigenous participants >50% F 13–21 years | Youth | Focus groups | YES |

| Wexler (2013) [141] | Northwest Alaska | Community | Inupiaq | 23 Indigenous participants (9 youth, 7 adults, 7 Elders) Youth: 14–21 years; Adults: 35–50 years; Elders: 60+ years. | Youth, adults and Elders | Focus groups and interviews; digital stories | BROAD |

| Wexler et al. (2013) [142] Wexler et al. (2014) [143] | Northwest Alaska | Community | Inupiaq | 20 Indigenous participants 10F 10M 11–18 years | Youth | Interviews (3 x 1 h for each participant) | BROAD |

| Wood et al. (2018) [144] | San Diego | Community | Kumeyaay Luiseno | 22 Indigenous participants 17F 5M 14–27 years | Youth and retrospective youth | In depth and semi-structured interviews; focus groups; surveys | YES |

Basic Resources for Survival

Safety and Stability

Relationships with Others

Culture and Spirituality

Knowledge, Opportunities and the Future

Identity

Resilience and Independence

Recreation and Interests

3.2.2. Indigenous Youth in the USA

Safety and Basic Needs

Relationships and Connection

Culture and Tradition

Cultural Identity and Pride

Looking to the Past and the Future

Being Healthy

3.2.3. Māori Youth in Aotearoa New Zealand

Belonging, Care and Support

Ahurea (Culture)

Mātauranga Māori (Māori Knowledge) and Mōhiotanga (Knowing)

Identity and Agency

Physical Health

3.2.4. Indigenous Youth in Australia

Basic Needs

Relationships

Culture

Aspirations for the Future

Identity

Recreational Activities and Interests

Physical and Mental Health

4. Discussion

Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Nation-Specific Themes and Exemplar Quotes

| CANADA |

Basic Resources for Survival

|

Safety and Stability

|

Relationships with Others

|

Culture and Spirituality

|

Knowledge, opportunities and the future

|

Identity

|

Resilience and Independence

|

Recreation and Interests

|

| AUSTRALIA |

Basic Needs

|

Relationships

|

Culture

|

Aspirations for the Future

|

Identity

|

Recreational Activities and Interests

|

Physical and Mental Health

|

| AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND |

Belonging, Care and Support

|

Ahurea (Culture)

|

mātauranga (knowledge) and mōhiotanga (knowing)

|

Identity and Agency

|

Physical Health

|

| USA |

Safety and Basic Needs

|

Relationships and Connection

|

Culture and Tradition

|

Cultural Identity and Pride

|

Looking to the past and future

|

Being Healthy

|

References

- The World Bank. Indigenous Peoples. 2019. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/indigenouspeoples#1 (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- Pulver, L.J.; Haswell, M.R.; Ring, I.; Waldon, J.; Clark, W.; Whetung, V.; Kinnon, D.; Graham, C.; Chino, M.; LaValley, J.; et al. Indigenous Health–Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States-Laying Claim to a Future that Embraces Health for Us All. In World Health Report-Financing for Universal Health Coverage Background Paper; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; No. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, C.; Nettleton, C.; Porter, J.; Willis, R.; Clark, S. Indigenous peoples’ health—Why are they behind everyone, everywhere? Lancet 2005, 366, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples: A Manual for National Human Rights Institutions. 2013. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/documents/issues/ipeoples/undripmanualfornhris.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- Anderson, I.; Robson, B.; Connolly, M.; Al-Yaman, F.; Bjertness, E.; King, A.; Tynan, M.; Madden, R.; Bang, A.; Coimbra, C.E.A.; et al. Indigenous and tribal peoples’ health (The Lancet–Lowitja Institute Global Collaboration): A population study. Lancet 2016, 388, 131–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. Focus on Geography Series, 2016 Census. 2016. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/fogs-spg/Facts-CAN-eng.cfm?Lang=Eng&GK=CAN&GC=01&TOPIC=9 (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. 2016. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-peoples/estimates-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-australians/latest-release#:~:text=There%20were%20798%2C400%20Indigenous%20people%20in%20Australia%20in,Indigenous%20population%2020.3%20years%2C%20Non-Indigenous%20population%2037.8%20years (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- Stats NZ—Taturanga Aotearoa. Māori Population Estimates: At 30 June 2020. Available online: https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/maori-population-estimates-at-30-june-2020 (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- USA Facts. How the Native American Population Changed Since the Last Census. 2022. Available online: https://usafacts.org/articles/how-the-native-american-population-changed-since-the-last-census/#:~:text=While%20the%20median%20age%20for%20all%20Americans%20is,to%20be%2065%20or%20older%20than%20Americans%20overall (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- Gillies, W.M.; Boden, J.M.; Friesen, M.D.; Macfarlane, S.; Fergusson, D.M. Ethnic Differences in Adolescent Mental Health Problems: Examining Early Risk Factors and Deviant Peer Affiliation. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2017, 26, 2889–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, M.L.; de Leeuw, S.N. Social determinants of health and the future well-being of Aboriginal children in Canada. Paediatr Child Health 2012, 17, 381–384. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. The State of Knowledge of Aboriginal Health: A Review of Aboriginal Public Health in Canada; National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Azzopardi, P.S.; Sawyer, S.M.; Carlin, J.B.; Degenhardt, L.; Brown, N.; Brown, A.; Patton, G. Health and wellbeing of Indigenous adolescents in Australia: A systematic synthesis of population data. Lancet 2018, 391, 766–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, G.C.; Sawyer, S.M.; Santelli, J.S.; Ross, D.A.; Afifi, R.; Allen, N.B.; Arora, M.; Azzopardi, P.; Baldwin, W.; Bonell, C.; et al. Our future: A Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet 2016, 387, 2423–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clifford, A.C.; Doran, C.M.; Tsey, K. A systematic review of suicide prevention interventions targeting indigenous peoples in Australia, United States, Canada and New Zealand. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Snijder, M.; Stapinski, L.; Lees, B.; Ward, J.; Conrod, P.; Mushquash, C.; Belone, L.; Champion, K.; Chapman, C.; Teesson, M.; et al. Preventing Substance Use Among Indigenous Adolescents in the USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Prev. Sci. 2020, 21, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Youth Detention Population in Australia 2021; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2021.

- Statistics Canada. Adult and Youth Correctional Statistics in Canada. 2020. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2020001/article/00016-eng.htm (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- Ministry of Justice. Youth Justice Indicators Summary Report; New Zealand Government: Wellington, New Zealand, 2020.

- Chase, Y.E.; Ullrich, J.S. A Connectedness Framework: Breaking the Cycle of Child Removal for Black and Indigenous Children. Int. J. Child Maltreat. Res. Policy Pract. 2022, 5, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada. Reducing the Number of Indigenous Children in Care. 2022. Available online: https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1541187352297/1541187392851 (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- Keddell, E.; Hyslop, I. Ethnic inequalities in child welfare: The role of practitioner risk perceptions. Child Fam. Soc. Work. 2019, 24, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SNAICC—National Voice for our Children. The Family Matters Report; SNAICC: Collingwood, VIC, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, E.; Christensen, J.; Andrew, P.; Aubry, T.; Belanger, Y.; Bird, C.; Birdsall-Jones, C.; Bonnycastle, M.M.; Brown, D.; Cherner, R.; et al. Indigenous Homelessness: Perspectives from Canada, Australia, and New Zealand; University of Manitoba Press: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- The New Economics Foundation. A Guide to Measuring Children’s Well-Being; The New Economics Foundation: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Well-Being Concepts. 2018. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hrqol/wellbeing.htm (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- Butler, T.L.; Anderson, K.; Garvey, G.; Cunningham, J.; Ratcliffe, J.; Tong, A.; Whop, L.J.; Cass, A.; Dickson, M.; Howard, K. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s domains of wellbeing: A comprehensive literature review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 233, 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gall, A.; Anderson, K.; Howard, K.; Diaz, A.; King, A.; Willing, E.; Connolly, M.; Lindsay, D.; Garvey, G. Wellbeing of Indigenous Peoples in Canada, Aotearoa (New Zealand) and the United States: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garvey, G.; Anderson, K.; Gall, A.; Butler, T.; Cunningham, J.; Whop, L.; Dickson, M.; Ratcliffe, J.; Cass, A.; Tong, A.; et al. What Matters 2 Adults (WM2Adults): Understanding the Foundations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Wellbeing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garvey, G.; Anderson, K.; Gall, A.; Butler, T.; Whop, L.; Arley, B.; Cunningham, J.; Dickson, M.; Cass, A.; Ratcliffe, J.; et al. The Fabric of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Wellbeing: A Conceptual Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, K.; Anderson, K.; Cunningham, J.; Cass, A.; Ratcliffe, J.; Whop, L.J.; Dickson, M.; Viney, R.; Mulhern, B.; Tong, A.; et al. What Matters 2 Adults: A study protocol to develop a new preference-based wellbeing measure with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults (WM2Adults). BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyer, S.M.; Gomersall, J.S.; Smithers, L.G.; Davy, C.; Coleman, D.T.; Street, J.M. Prevalence and characteristics of overweight and obesity in indigenous Australian children: A systematic review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 1365–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Geia, L.; Broadfield, K.; Grainger, D.; Day, A.; Watkin-Lui, F. Adolescent and young adult substance use in Australian Indigenous communities: A systematic review of demand control program outcomes. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2018, 42, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacPhail, C.; McKay, K. Social determinants in the sexual health of adolescent Aboriginal Australians: A systematic review. Health Soc. Care Community 2018, 26, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarivate Analytics. Endnote 20; Clarivate Analytics: Boston, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- NVivo; Version 12; QSR International Pty Ltd.: Burlington, MA, USA, 2020.

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada. Ongoing Negotiations. 2020. Available online: https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100030285/1529354158736#chp3 (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Aylward, E.; Abu-Zahra, N.; Giles, A. Mobility and Nunavut Inuit youth: Lessons from Northern Youth Abroad. J. Youth Stud. 2015, 18, 553–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, H.; Mulcahy, G.A.; Forchuk, C.; Edmunds, K.A.; Haldenby, A.; Lopez, R. Uprooted and displaced: A critical narrative study of homeless, aboriginal, and newcomer girls in Canada. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2009, 30, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, H.J.; McPherson, G.; Peterson, R.; Newman, V.; Cranmer, B. Our land, our language: Connecting dispossession and health equity in an indigenous context. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2012, 44, 44–63. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, N.; Walton, P.; Drolet, J.; Tribute, T.; Jules, G.; Main, T.; Arnouse, M. Melq’ilwiye: Coming together—Intersections of identity, culture, and health for urban aboriginal youth. CJNR Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2013, 45, 36–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerlach, A.J.; Browne, A.J.; Greenwood, M. Engaging indigenous families in a community-based indigenous early childhood programme in British Columbia, Canada: A cultural safety perspective. Health Soc. Care Community 2017, 25, 1763–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatala, A.R.; Pearl, T.; Bird-Naytowhow, K.; Judge, A.; Sjoblom, E.; Liebenberg, L. I Have Strong Hopes for the Future: Time Orientations and Resilience Among Canadian Indigenous Youth. Qual. Health Res. 2017, 27, 1330–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaak, C.A.; Marchessault, G. Meaning of Health: The Perspectives of Aboriginal Adults and Youth in a Northern Manitoba First Nations Community. Can. J. Diabetes 2008, 32, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kral, M.J. The Weight on Our Shoulders Is Too Much, and We Are Falling. Med. Anthropol. Q. 2013, 27, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kral, M.J.; Idlout, L.; Minore, J.B.; Dyck, R.J.; Kirmayer, L.J. Unikkaartuit: Meanings of well-being, unhappiness, health, and community change among inuit in Nunavut, Canada. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2011, 48, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyoung June, Y.; Landais, E.; Kolahdooz, F.; Sharma, S. Framing Health Matters. Factors Influencing the Health and Wellness of Urban Aboriginal Youths in Canada: Insights of In-Service Professionals, Care Providers, and Stakeholders. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 881–890. [Google Scholar]

- Latimer, M.; Sylliboy, J.R.; Francis, J.; Amey, S.; Rudderham, S.; Finley, G.A.; MacLeod, E.; Paul, K. Co-creating better healthcare experiences for First Nations children and youth: The FIRST approach emerges from Two-Eyed seeing. Paediatr. Neonatal Pain 2020, 2, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lines, L.-A.; Jardine, C.G. Connection to the land as a youth-identified social determinant of Indigenous Peoples’ health. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, J.P.; Willox, A.C.; Ford, J.D.; Shiwak, I.; Wood, M. Protective factors for mental health and well-being in a changing climate: Perspectives from inuit youth in Nunatsiavut, Labrador. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 141, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, T.-L.F.; Coppola, A.M.; Sabiston, C.M. I’m thankful for being Native and my body is part of that: The body pride experiences of young Aboriginal women in Canada. Body Image 2014, 11, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikraszewicz, K.; Richmond, C. Paddling the Biigtig: Mino biimadisiwin practiced through canoeing. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 240, 112548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navia, D.; Henderson, R.I.; First Charger, L. Uncovering Colonial Legacies: Voices of Indigenous Youth on Child Welfare (Dis)Placements. Anthropol. Educ. Q. 2018, 49, 146–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oliver, C. Inclusive foster care: How foster parents support cultural and relational connections for Indigenous children. Child Fam. Soc. Work. 2020, 25, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, J.; Gabel, C. Using Photovoice to understand barriers and enablers to Southern Labrador Inuit intergenerational interaction. J. Intergeneration. Relatsh. 2018, 16, 351–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlee, B.; O’Neil, J. The Dene Way of Life: Perspectives on Health from Canada’s North. J. Can. Stud. 2007, 41, 112–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, S.D.; Wabano, M.J.; Corbiere, R.G.; Restoule, B.M.; Russell, K.C.; Young, N.L. Connecting to the Good Life through outdoor adventure leadership experiences designed for Indigenous youth. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2015, 15, 350–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasakamoose, J.; Scerbe, A.; Wenaus, I.; Scandrett, A. First Nation and Métis Youth Perspectives of Health: An Indigenous Qualitative Inquiry. Qual. Inq. 2016, 22, 636–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, J.; Poudrier, J.; Chad, K.; Jeffrey, B.; Thomas, R.; Burnouf, K. In Their Own Words: First Nations Girls’ Resilience as Reflected through Their Understandings of Health. Pimatisiwin 2013, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, E.; Masuda, J.R. Right to a healthy city? Examining the relationship between urban space and health inequity by Aboriginal youth artist-activists in Winnipeg. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 91, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, S.J.; Thomas, S.; O’Neill, K.; Brondgeest, C.; Thomas, J.; Beltran, J.; Hunt, T.; Yassi, A. Visual storytelling, intergenerational environmental justice and indigenous sovereignty: Exploring images and stories amid a contested oil pipeline project. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thompson, G.E.; Cameron, R.E.; Fuller-Thomson, E. Walking the red road: The role of First Nations grandparents in promoting cultural well-being. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2013, 76, 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victor, J.; Linds, W.; Episkenew, J.-A.; Goulet, L.; Benjoe, D.; Brass, D.; Pandey, M.; Schmidt, K. Kiskenimisowin (self-knowledge): Co-researching Wellbeing with Canadian First Nations Youth Through Participatory Visual Methods. Int. J. Indig. Health 2016, 11, 262–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yuen, F.; Linds, W.; Goulet, L.; Episkenew, J.; Ritenburg, H.; Schmidt, K. You Might as well Call it Planet of the Sioux: Indigenous Youth, Imagination, and Decolonization. Pimatisiwin 2013, 11, 269–281. [Google Scholar]

- Ansloos, J.P.; Wager, A.C.; Dunn, N.S. Preventing Indigenous youth homelessness in Canada: A qualitative study on structural challenges and upstream prevention in education. J. Community Psychol. 2021, 50, 1918–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, B.-J.; Lesperance, A.; Foote, I.; Firestone, M.; Smylie, J. Meeting Indigenous youth where they are at: Knowing and doing with 2SLGBTTQQIA and gender non-conforming Indigenous youth: A qualitative case study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nightingale, E.; Richmond, C.A.M. Reclaiming Mountain Lake: Applying environmental repossession in Biigtigong Nishnaabeg territory, Canada. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 272, 113706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njeze, C.; Bird-Naytowhow, K.; Pearl, T.; Hatala, A.R. Intersectionality of Resilience: A Strengths-Based Case Study Approach with Indigenous Youth in an Urban Canadian Context. Qual. Health Res. 2020, 30, 2001–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, A.L. Experiences and well-being among Indigenous former youth in care within Canada. Child Abus. Negl. 2022, 123, 105395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, K.; Jardine, C. Our Way of Life: Importance of Indigenous Culture and Tradition to Physical Activity Practices. Int. J. Indig. Health 2016, 11, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahi, G.; Wilson, J.; Oster, R.; Rain, P.; Jack, S.M.; Gittelsohn, J.; Kandasamy, S.; de Souza, R.J.; Martin, C.L.; Toth, E.; et al. Strategies for promoting healthy nutrition and physical activity among young children: Priorities of two indigenous communities in Canada. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, nzz137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walls, M.; Hautala, D.; Hurley, J. Rebuilding our community: HearinG silenced voices on Aboriginal youth suicide. Transcult. Psychiatry 2014, 51, 47–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walsh, R.; Danto, D.; Sommerfeld, J. Land-based intervention: A qualitative study of the knowledge and practices associated with one approach to mental health in a Cree community. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 18, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ward, L.M.; Hill, M.J.; Antane, N.; Chreim, S.; Olsen Harper, A.; Wells, S. The Land Nurtures Our Spirit: Understanding the Role of the Land in Labrador Innu Wellbeing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatala, A.R.; Morton, D.; Njeze, C.; Bird-Naytowhow, K.; Pearl, T. Re-imagining miyo-wicehtowin: Human-nature relations, land-making, and wellness among Indigenous youth in a Canadian urban context. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 230, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatala, A.R.; Njeze, C.; Morton, D.; Pearl, T.; Bird-Naytowhow, K. Land and nature as sources of health and resilience among Indigenous youth in an urban Canadian context: A photovoice exploration. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebenberg, L.; Reich, J.; Denny, J.F.; Gould, M.R.; Hutt-MacLeod, D. Two-eyed Seeing for youth wellness: Promoting positive outcomes with interwoven resilience resources. Transcult. Psychiatry 2022, 13634615221111025. [Google Scholar]

- Nightingale, E.; Richmond, C. Reclaiming Land, Identity and Mental Wellness in Biigtigong Nishnaabeg Territory. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sloan Morgan, O.V.; Thomas, K.; McNab-Coombs, L. Envisioning healthy futures: Youth perceptions of justice-oriented environments and communities in Northern British Columbia Canada. Health Place 2022, 76, 102817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K.D.; Oosthuizen, J.; Beerenfels, S.; Rowell, A.-M.C. Making the best of the early years: The Tambellup way. Rural. Remote Health 2010, 10, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, M.J.; Williamson, A.B.; Fernando, P.; Redman, S.; Vincent, F. There’s a housing crisis going on in Sydney for Aboriginal people: Focus group accounts of housing and perceived associations with health. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Canuto, K.; Towers, K.; Riessen, J.; Perry, J.; Bond, S.; Ah Chee, D.; Brown, A. Anybody can make kids: It takes a real man to look after your kids: Aboriginal men’s discourse on parenting. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, C.; Clark, Y.; Hokke, S.; Hampton, A.; Atkinson, C.; Andrews, S. Healing the Past by Nurturing the Future: Aboriginal parents’ Views of What Helps Support Recovery from Complex Trauma: Indigenous Health and Well-Being: Targeted Primary Health Care across the Life Course; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chenhall, R.; Senior, K. Those Young People All Crankybella. Int. J. Ment. Health 2009, 38, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, R.; Stanley, R.; Probst, Y.; McMahon, A. Culture and healthy lifestyles: A qualitative exploration of the role of food and physical activity in three urban Australian Indigenous communities. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2017, 41, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennison, S.; Smallbone, H.; Stewart, A.; Freiberg, K.; Teague, R. My life is separated: An examination of the challenges and barriers to parenting for Indigenous fathers in prison. Br. J. Criminol. 2014, 54, 1089–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gee, G.; Lesniowska, R.; Santhanam-Martin, R.; Chamberlain, C. Breaking the cycle of trauma—Koori parenting, what works for us. J. First Peoples Child Fam. Rev. 2022, 15, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.; Dudgeon, P.; Crockett, J. Listen, Look & Learn: Exploring Cultural Obligations of Elders and Older Aboriginal People; Taylor & Francis: Oxfordshire, UK, 2020; pp. 193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Helmer, J.; Senior, K.; Davison, B.; Vodic, A. Improving sexual health for young people: Making sexuality education a priority. Sex Educ. 2015, 15, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, F.H.; Jacups, S.P.; Vickery, A.J.; Bowman, D.M.J.S. Ecohealth and Aboriginal testimony of the nexus between human health and place. EcoHealth 2007, 4, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kickett-Tucker, C.S. Moorn (Black)? Djardak (White)? How come I don’t fit in Mum? Exploring the racial identity of Australian Aboriginal children and youth. Health Sociol. Rev. 2009, 18, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kiraly, M.; James, J.; Humphreys, C. It’s a Family Responsibility: Family and Cultural Connection for Aboriginal Children in Kinship Care. Child. Aust. 2015, 40, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruske, S.; Belton, S.; Wardaguga, M.; Narjic, C. Growing up our way: The first year of life in remote aboriginal Australia. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 22, 777–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowell, A.; Maypilama, L.; Fasoli, L.; Guyula, Y.; Guyula, A.; Yunupiŋu, M.; Godwin-Thompson, J.; Gundjarranbuy, R.; Armstrong, E.; Garrutju, J.; et al. The ‘invisible homeless’—Challenges faced by families bringing up their children in a remote Australian Aboriginal community. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCalman, J.; Benveniste, T.; Wenitong, M.; Saunders, V.; Hunter, E. It’s all about relationships: The place of boarding schools in promoting and managing health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander secondary school students. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 113, 104954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, H.M.; Young, C.; Nixon, J.; Talbot-McDonnell, M.; Cutmore, M.; Tong, A.; Craig, J.C.; Woolfenden, S. Parents’ and carers’ views on factors contributing to the health and wellbeing of urban Aboriginal children. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2020, 44, 12992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajer, N.; Bessarab, D.; Earnest, J. There should be more help out here! A qualitative study of the needs of Aboriginal adolescents in rural Australia. Rural. Remote Health 2009, 9, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murrup-Stewart, C.; Whyman, T.; Jobson, L.; Adams, K. Connection to Culture Is Like a Massive Lifeline: Yarning with Aboriginal Young People about Culture and Social and Emotional Wellbeing. Qual. Health Res. 2021, 31, 1833–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Povey, J.; Sweet, M.; Nagel, T.; Mills, P.P.J.R.; Stassi, C.P.; Puruntatameri, A.M.A.; Lowell, A.; Shand, F.; Dingwall, K. Drafting the Aboriginal and Islander Mental Health Initiative for Youth (AIMhi-Y) App: Results of a formative mixed methods study. Internet Interv. 2020, 21, 100318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priest, N.; Mackean, T.; Davis, E.; Briggs, L.; Waters, E. Aboriginal perspectives of child health and wellbeing in an urban setting: Developing a conceptual framework. Health Sociol. Rev. 2012, 21, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priest, N.; Mackean, T.; Davis, E.; Waters, E.; Briggs, L. Strengths and challenges for Koori kids: Harder for Koori kids, Koori kids doing well—Exploring Aboriginal perspectives on social determinants of Aboriginal child health and wellbeing. Health Sociol. Rev. 2012, 21, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priest, N.; Thompson, L.; Mackean, T.; Baker, A.; Waters, E. Yarning up with Koori kids—Hearing the voices of Australian urban Indigenous children about their health and well-being. Ethn. Health 2017, 22, 631–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senior, K.A.; Chenhall, R.D. Boyfriends, babies and basketball: Present lives and future aspirations of young women in a remote Australian Aboriginal community. J. Youth Stud. 2012, 15, 369–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A.; Merlino, A.; Christie, B.; Adams, M.; Bonson, J.; Osborne, R.; Judd, B.; Drummond, M.; Aanundsen, D.; Fleay, J. ‘Dudes Are Meant to be Tough as Nails’: The Complex Nexus Between Masculinities, Culture and Health Literacy from the Perspective of Young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Males—Implications for Policy and Practice. Am. J. Men’s Health 2020, 14, 1557988320936121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, A.B.; Raphael, B.; Redman, S.; Daniels, J.; Eades, S.J.; Mayers, N. Emerging themes in Aboriginal child and adolescent mental health: Findings from a qualitative study in Sydney, New South Wales. Med. J. Aust. 2010, 192, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, C.; Tong, A.; Nixon, J.; Fernando, P.; Kalucy, D.; Sherriff, S.; Clapham, K.; Craig, J.C.; Williamson, A. Perspectives on childhood resilience among the Aboriginal community: An interview study. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2017, 41, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, S.; Park, J.; Tipene-Leach, D.; Finau, S.; Lennan, M. Infant care practices in New Zealand: A cross-cultural qualitative study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2001, 53, 1135–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, S.; Stockdale-Frost, A.; Rolls, R.; Tipene-Leach, D. The Wahakura: A qualitative study of the flax bassinet as a sleep location for New Zealand Māori infants. N. Z. Med. J. 2015, 128, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Adcock, A.; Cram, F.; Edmonds, L.; Lawton, B. He Tamariki Kokoti Tau: Families of Indigenous Infants Talk about Their Experiences of Preterm Birth and Neonatal Intensive Care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beavis, B.S.; McKerchar, C.; Maaka, J.; Mainvil, L.A. Exploration of Māori household experiences of food insecurity. J. Dietit. Assoc. Aust. 2019, 76, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, T.; Calder-Dawe, O.; Jensen-Lesatele, V. ‘You can’t really define it can you?’ Rangatahi perspectives on hauora and wellbeing. J. R. Soc. N. Z. 2022, 52, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamley, L.; Le Grice, J.; Greaves, L.; Groot, S.; Latimer, C.L.; Renfrew, L.; Parkinson, H.; Gillon, A.; Clark, T.C. Te Tapatoru: A model of whanaungatanga to support rangatahi wellbeing. N. Z. J. Soc. Sci. Online 2022, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moewaka Barnes, H.; Henwood, W.; Murray, J.; Waiti, P.; Pomare-Peita, M.; Bercic, S.; Chee, R.; Mitchell, M.; McCreanor, T. Noho Taiao: Reclaiming Māori science with young people. Glob. Health Promot. 2019, 26, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Page, C.; Rona, S. Kia Manaaki te Tangata: Rangatahi Māori Perspectives on Their Rights as Indigenous Youth to Whānau Ora and Collective Wellbeing. Int. J. Stud. Voice 2022, 7, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ayunerak, P.; Alstrom, D.; Moses, C.; Charlie, J., Sr.; Rasmus, S.M. Yup’ik culture and context in Southwest Alaska: Community member perspectives of tradition, social change, and prevention. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2014, 54, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bjorum, E. Those Are Our People and That’s Our Family: Wabanaki Perspectives on Child Welfare Practice in Their Communities. J. Public Child Welf. 2014, 8, 279–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnette, C.E.; Cannon, C. It will always continue unless we can change something: Consequences of intimate partner violence for indigenous women, children, and families. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2014, 5, 24585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cross, S.L.; Day, A. American Indian Grand Families: Eight Adolescent and Grandparent Dyads Share Perceptions on Various Aspects of the Kinship Care Relationship. J. Ethn. Cult. Divers. Soc. Work. 2008, 17, 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla, R.L.; Marchetti, A.M.; Sechrest, E.A.; White, J.L. ‘All the men here have the Peter Pan syndrome—They don’t want to grow up’: Navajo adolescent mothers’ intimate partner relationships—A 15-year perspective. Violence Against Women 2010, 16, 743–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Schweinitz, P.A.; Nation, C.; DeCou, C.R.; Stewart, T.J.; Allen, J. Cultural perspectives on suicide from a rural Athabascan Alaska Native community: Wellness teams as a strengths-based community response. J. Rural. Ment. Health 2017, 41, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCou, C.R.; Skewes, M.C.; López, E.D.S. Traditional living and cultural ways as protective factors against suicide: Perceptions of Alaska Native university students. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2013, 72, 20968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, T.; Rasmus, S.; Allen, J. Being useful: Achieving indigenous youth involvement in a community-based participatory research project in Alaska. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2012, 71, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, B.M. Promoting global health and well-being of Indigenous youth through the connection of land and culture-based activism. Glob. Health Promot. 2019, 26, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friesen, B.J.; Cross, T.L.; Jivanjee, P.; Thirstrup, A.; Bandurraga, A.; Gowen, L.K.; Rountree, J. Meeting the transition needs of urban American Indian/Alaska Native youth through culturally based services. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 42, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodkind, J.R.; Hess, J.M.; Gorman, B.; Parker, D.P. “We’re still in a struggle”: Diné resilience, survival, historical trauma, and healing. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 22, 1019–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hand, C.A. An Ojibwe perspective on the welfare of children: Lessons of the past and visions for the future. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2006, 28, 20–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, L.E.; Stiffman, A.R.; Brown, E. Unraveling Cultural Threads: A Qualitative Study of Culture and Ethnic Identity Among Urban Southwestern American Indian Youth Parents and Elders. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2006, 15, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacson, M.J.; Bott-Knutson, R.C.; Fishback, M.B.; Varnum, A.; Brandenburger, S. Native Elder and Youth Perspectives on Mental Well-Being, the Value of the Horse, and Navigating Two Worlds. Online J. Rural. Nurs. Health Care 2018, 18, 265–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.P.; Boyd, K.; Allen, J.; Rasmus, S.; Henderson, T. ‘We raise our grandchildren as our own:’ Alaska native grandparents raising grandchildren in Southwest Alaska. J. Cross Cult. Gerontol. 2018, 33, 265–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnette, C.E.; Lesesne, R.; Temple, C.; Rodning, C.B. Family as the conduit to promote indigenous women and men’s enculturation and wellness: ‘I wish I had learned earlier’. J. Evid. Based Soc. Work. 2020, 17, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nu, J.; Bersamin, A. Collaborating with Alaska Native Communities to Design a Cultural Food Intervention to Address Nutrition Transition. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. Res. Educ. Action 2017, 11, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmus, S.M.; Allen, J.; Ford, T. “Where I have to learn the ways how to live”: Youth resilience in a Yup’ik village in Alaska. Transcult. Psychiatr. 2014, 51, 713–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Strickland, C.J.; Walsh, E.; Cooper, M. Healing Fractured Families: Parents’ and Elders’ Perspectives on the Impact of Colonization and Youth Suicide Prevention in a Pacific Northwest American Indian Tribe. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2006, 17, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinidad, A.M.O. Toward kuleana (responsibility): A case study of a contextually grounded intervention for Native Hawaiian youth and young adults. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2009, 14, 488–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trout, L.; Wexler, L.; Moses, J. Beyond two worlds: Identity narratives and the aspirational futures of Alaska Native youth. Transcult. Psychiatr. 2018, 55, 800–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- West, A.E.; Williams, E.; Suzukovich, E.; Strangeman, K.; Novins, D. A mental health needs assessment of urban American Indian youth and families. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2012, 49, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wexler, L.M. Inupiat youth suicide and culture loss: Changing community conversations for prevention. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 63, 2938–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wexler, L. Identifying Colonial Discourses in Inupiat Young People’s Narratives as a Way to Understand the No Future of Inupiat Youth Suicide. Am. Indian Alsk. Nativ. Ment. Health Res. 2009, 16, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wexler, L. Looking across three generations of Alaska Natives to explore how culture fosters indigenous resilience. Transcult. Psychiatr. 2013, 51, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wexler, L.; Jernigan, K.; Mazzotti, J.; Baldwin, E.; Griffin, M.; Joule, L.; Garoutte, J.; CIPA Team. Lived Challenges and Getting Through Them: Alaska Native Youth Narratives as a Way to Understand Resilience. Health Promot. Pract. 2013, 15, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wexler, L.; Joule, L.; Garoutte, J.; Mazziotti, J.; Hopper, K. “Being responsible, respectful, trying to keep the tradition alive”: Cultural resilience and growing up in an Alaska Native community. Transcult Psychiatr. 2014, 51, 693–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L.; Kamper, D.; Swanson, K. Spaces of hope? Youth perspectives on health and wellness in indigenous communities. Health Place 2018, 50, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trask, M.B. Historical and contemporary Hawaiian self-determination: A Native Hawaiian perspective. Ariz. J. Int. Comp. L. 1991, 8, 77. [Google Scholar]

- Carlton, B.S.; Goebert, D.A.; Miyamoto, R.H.; Andrade, N.N.; Hishinuma, E.S.; Makini, J.G.K.; Yuen, N.Y.; Bell, C.K.; McCubbin, L.D.; Else, R.; et al. Resilience, Family Adversity and Well-Being Among Hawaiian and Non-Hawaiian Adolescents. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2006, 52, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. The Indigenous World 2022: Hawaii. 2022. Available online: https://www.iwgia.org/en/usa/4688-iw-2022-hawai-i.html (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. The Indigenous World 2022: United States of America. 2022. Available online: https://www.iwgia.org/en/usa/4684-iw-2022-united-states-of-america.html (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- New Zealand Government. Story: Māori. 2022. Available online: https://teara.govt.nz/en/maori (accessed on 22 May 2022).

- Reid, P.; Cormack, D.; Paine, S.J. Colonial histories, racism and health—The experience of Māori and Indigenous peoples. Public Health 2019, 172, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Indigenous Australians: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People. 2022. Available online: https://aiatsis.gov.au/explore/indigenous-australians-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-people (accessed on 22 May 2022).

- ANTaR. Who We Are. 2022. Available online: https://antar.org.au/our-work/who-we-are (accessed on 22 May 2022).

- Kleinert, S.; Neale, M.; Bancroft, R.; Anderson, T. The Oxford Companion to Aboriginal Art and Culture; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- McCoy, B. ‘Living Between two Worlds’: Who is Living in Whose Worlds? Australas. Psychiatr. 2009, 17 (Suppl. S1), S20–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, C.A.; Fitzgerald, M.O. Living in Two Worlds: The American Indian Experience Illustrated; World Wisdom: Room, Hong Kong, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, H.K.; Felmlee, D.H.; Conger, R.D. The Social Context of Adolescent Friendships: Parents, Peers, and Romantic Partners. Youth Soc. 2014, 49, 679–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagno, A.E.; Brayboy, B.M.J. Culturally Responsive Schooling for Indigenous Youth: A Review of the Literature. Rev. Educ. Res. 2008, 78, 941–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson-Barrett, E.; Lee-Hammond, L. Strengthening Identities and Involvement of Aboriginal Children through Learning on Country. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2018, 43, 86–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogarty, W.; Lovell, M.; Langenberg, J.; Heron, M. Deficit Discourse and Strengths-Based Approaches: Changing the Narrative of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Wellbeing; The Lowitja Institute: Melbourne, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hyett, S.L.; Gabel, C.; Marjerrison, S.; Schwartz, L. Deficit-Based Indigenous Health Research and the Stereotyping of Indigenous Peoples. Can. J. Bioeth. Rev. Can. Bioéthique 2019, 2, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adelson, N. The embodiment of inequity: Health disparities in aboriginal Canada. Can. J. Public Health Rev. Can. Sante Publique 2005, 96 (Suppl. S2), S45–S61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, L.; Zuk, A.M.; Tsuji, L.J.S. Health and Wellness Impacts of Traditional Physical Activity Experiences on Indigenous Youth: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzopardi, P.S.; Kennedy, E.C.; Patton, G.C.; Power, R.; Roseby, R.D.; Sawyer, S.M.; Brown, A.D. The quality of health research for young indigenous australians: Informing health priority, intervention and future research need. Turk. Pediatri. Arsivi. 2013, 48, 74. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, N.; Tulve, N.S.; Heggem, D.T.; Bailey, K. Review of built and natural environment stressors impacting American-Indian/Alaska-Native children. Rev. Environ. Health 2018, 33, 349–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bombak, A.E.; Bruce, S.G. Self-rated health and ethnicity: Focus on indigenous populations. Int. J. Circumpolar Health. 2012, 71, 18538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bombay, A.; Matheson, K.; Anisman, H. The intergenerational effects of Indian residential schools: Implications for the concept of historical trauma. Transcult. Psychiatry 2014, 51, 320–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hawkins, E.H.; Cummins, L.H.; Marlatt, G.A. Preventing Substance Abuse in American Indian and Alaska Native Youth: Promising Strategies for Healthier Communities. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 130, 304–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hishinuma, E.S.; Smith, M.D.; McCarthy, K.; Lee, M.; Goebert, D.A.; Sugimoto-Matsuda, J.J.; Andrade, N.N.; Philip, J.B.; Chung-Do, J.J.; Hamamoto, R.S.; et al. Longitudinal Prediction of Suicide Attempts for a Diverse Adolescent Sample of Native Hawaiians, Pacific Peoples, and Asian Americans. Arch. Suicide Res. 2018, 22, 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongen, C.; McCalman, J.; Bainbridge, R.; Tsey, K. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander maternal and child health and wellbeing: A systematic search of programs and services in Australian primary health care settings. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kairuz, C.A.; Casanelia, L.M.; Bennett-Brook, K.; Coombes, J.; Yadav, U.N. Impact of racism and discrimination on physical and mental health among Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander peoples living in Australia: A systematic scoping review. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilian, A.; Williamson, A. What is known about pathways to mental health care for Australian Aboriginal young people?: A narrative review. Int. J. Equity Health 2018, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kirmayer, L.J.; Brass, G.M.; Tait, C.L. The mental health of Aboriginal peoples: Transformations of identity and community. Can. J. Psychiatry 2000, 45, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kirmayer, L.; Simpson, C.; Cargo, M. Healing traditions: Culture, community and mental health promotion with Canadian Aboriginal peoples. Australas. Psychiatry 2003, 11 (Suppl. S1), S15–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.M.K.I.; Alameda, C.K. Social determinants of health for Native Hawaiian children and adolescents. Hawaii Med. J. 2011, 70 (Suppl. S2), 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lucero, N.M.; Leake, R. Expressions of Culture in American Indian/Alaska Native Tribal Child Welfare Work: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis. J. Public Child Welf. 2016, 10, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priest, N.; Mackean, T.; Waters, E.; Davis, E.; Riggs, E. Indigenous child health research: A critical analysis of Australian studies. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2009, 33, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rountree, J.; Smith, A. Strength-based well-being indicators for Indigenous children and families: A literature review of Indigenous communities’ identified well-being indicators. Am. Indian Alsk. Nativ. Ment. Health Res. 2016, 23, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, A.J.; Hetherington, R. A decade of research in Inuit children, youth, and maternal health in Canada: Areas of concentrations and scarcities. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2012, 71, 18383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Smallwood, R.; Woods, C.; Power, T.; Usher, K. Understanding the Impact of Historical Trauma Due to Colonization on the Health and Well-Being of Indigenous Young Peoples: A Systematic Scoping Review. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2021, 32, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Population | Title/Abstract search: “First Nation *” OR “First people *” OR Indigenous OR Aborig * OR “Torres Strait Islander *” OR “Torres Strait” OR “Indigenous Australia *” or “First Australia *” OR “American Indian *” OR Inuit* OR Māori* OR Maori * OR “Native American *” OR ((Canadian OR Canada) AND Aborigin *) OR “native Canadian” OR “Indigenous population*” OR Metis OR Métis OR “Alaska * Native” OR “Native Alaska *” OR “Native Hawaiian *” OR tribal |

| Population controlled vocabulary | MH “Indigenous peoples” |

| Wellbeing terms | Title/Abstract search: wellbeing OR well-being OR SEWB OR “quality of life” OR HR-QOL OR HRQOL OR QOL OR wellness OR “life quality” OR “quality adjusted life year” OR “QALY” |

| Wellbeing controlled vocabulary | (MM “Child Welfare”) OR (MH “Infant Welfare”) OR (MM “Quality of Life”) OR (MM “Quality-Adjusted Life Years”) |

| Youth terms | Title/Abstract search: child * OR children OR infant OR toddler OR ‘preschool’ OR school OR teen * OR “young adult” OR youth * OR adolescen* OR paediatric OR “young people” OR “juvenile” OR pepe OR pepi OR tamariki OR rangatahi |

| Youth controlled vocabulary | (MM “Adolescent”) OR (MH “Child+”) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anderson, K.; Elder-Robinson, E.; Gall, A.; Ngampromwongse, K.; Connolly, M.; Letendre, A.; Willing, E.; Akuhata-Huntington, Z.; Howard, K.; Dickson, M.; et al. Aspects of Wellbeing for Indigenous Youth in CANZUS Countries: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13688. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013688

Anderson K, Elder-Robinson E, Gall A, Ngampromwongse K, Connolly M, Letendre A, Willing E, Akuhata-Huntington Z, Howard K, Dickson M, et al. Aspects of Wellbeing for Indigenous Youth in CANZUS Countries: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(20):13688. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013688

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnderson, Kate, Elaina Elder-Robinson, Alana Gall, Khwanruethai Ngampromwongse, Michele Connolly, Angeline Letendre, Esther Willing, Zaine Akuhata-Huntington, Kirsten Howard, Michelle Dickson, and et al. 2022. "Aspects of Wellbeing for Indigenous Youth in CANZUS Countries: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 20: 13688. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013688