Lung Cancer Patients’ Conceptualization of Care Coordination in Selected Public Health Facilities of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

Abstract

1. Study Background

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Settings

2.3. Study Participants and Recruiting Approach

2.4. Data Collection and Sampling

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Respondents’ Characteristics

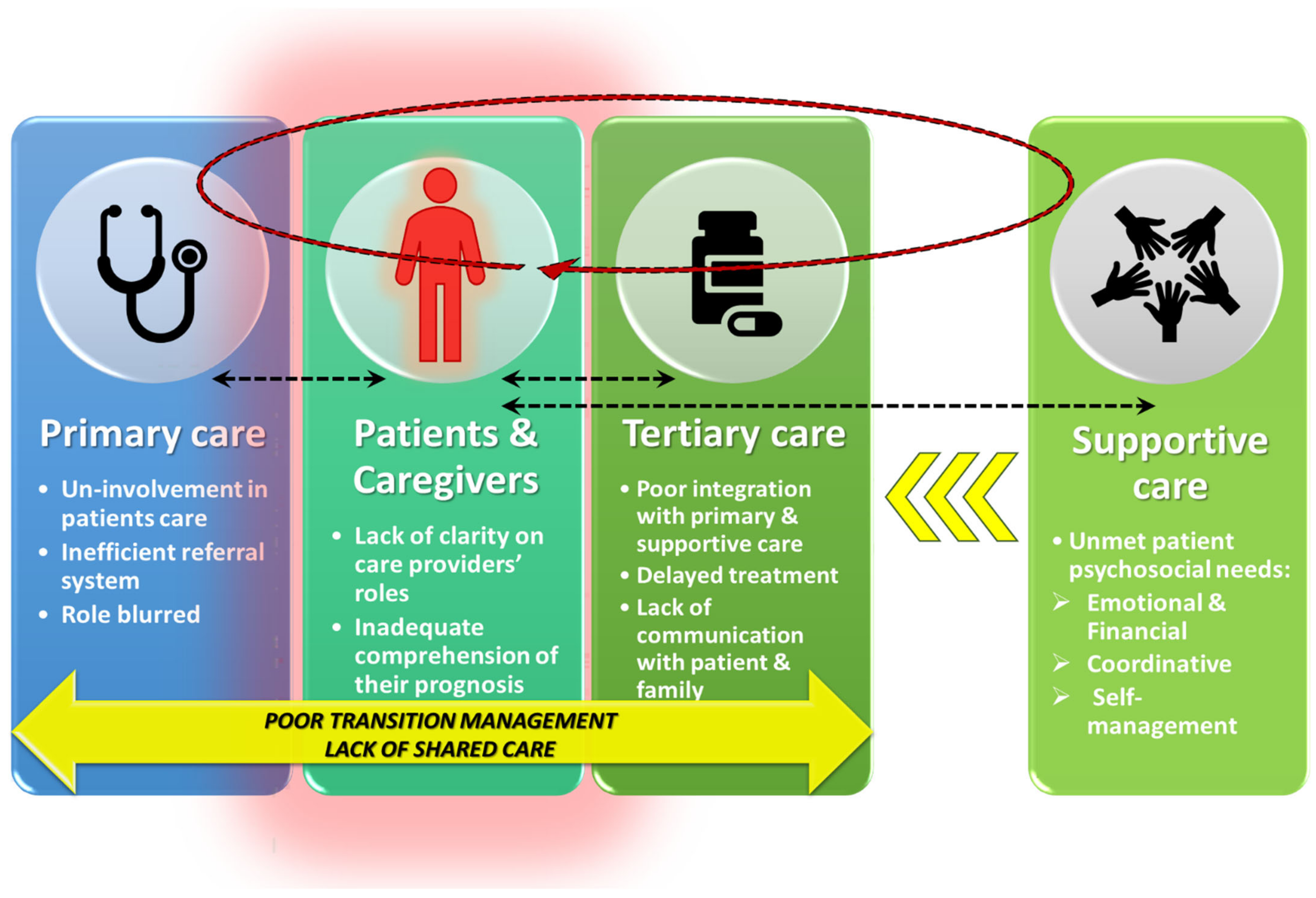

3.2. Lack of Integrated Systems of Care

Yes, there were delays in my treatment, mama [ma’am], and the process of care caused the problems that caused delays; there is a system used to attend to patients. They don’t attend to you even if you are sick to death because you need to go through their referral and booking system, which fails to work most of the time.(Respondent 11)

They [healthcare providers] were clueless because they all started from scratch with their search. Everyone started from the beginning because no one knew anything about his condition. Even the referral letter was just blank; we saw it. The only written thing was that this patient is referred to hospital B and from there to hospital C for a scan, but nothing says to scan for what and what they managed to find. When we got to hospital C, it was the same thing; in fact, that day they even delayed admitting him because they didn’t know the patient was going to be admitted for what.(Respondent 21: Proxy)

Perhaps because I have cancer, I don’t know, maybe they are not saying, perhaps they are thinking I’m supposed to be dead or something like that, I don’t know; perhaps that’s why they’re pushing the dates back so far, and my care is delayed.(Respondent 2)

The hospitals are overwhelmed with the numbers, and I believe it burdened the caretakers, nurses, maybe including the doctors. As a result, they see us now as numbers rather than as humans; that’s where you’ll see the patients complain. So maybe those are the things that may need to be addressed.(Respondent 2)

One thing I realized is that the public hospitals are overloaded with patients, but every doctor that I met was respectful, and the nurses were respectful. I can’t say they did anything; I would not be happy with my father, whom I was taking care of.(Respondent 18: Proxy)

I would say they worked well together because I feel everything is going well, and if I happen to miss my appointment date, they can accommodate me. They phone to organize a new date, which shows that the doctors are working well together.(Respondent 6)

But in terms of the attitudes, honestly, I can’t complain about the nurses. I can’t complain about the doctors; everyone was respectful. I wish they could keep up with that because you know what impresses the patients is not whether they get medication or not sometimes; it’s just the treatment. If they don’t respect the patient, that itself can kill the patient.(Respondent 14)

3.3. Lack of Care Providers’ Engagement with Patients

When my husband was admitted to hospital A, the biggest problem was that they did not explain what was going on. This one time, they made us wait up to 3 weeks, just waiting to do a scan, and for that three weeks, they were not updating us as to what was going on, and we couldn’t visit him in hospital because it was COVID days… Now when doctors come, they come with students. They don’t explain anything to patients, but their students and students also don’t explain anything to patients, and my husband was admitted for three weeks with no information; they kept saying he needed to do some tests but then not specific about what tests, so that was very disappointing.(Respondent 16: Proxy)

I don’t know what was wrong with hospital A; I told you, we tried many times to communicate with the doctor there and even asked the nurse if they could give us even just 2 min as a family; we needed answers, but it was hard.(Respondent 4)

I would say that available health workers do their job well, but I wouldn’t know their communication because the challenge with the big doctors that come to the wards, we couldn’t communicate with them and ask them questions; we were not given that chance even though there was this one particular doctor that we would raise our concerns with, but you would see that he does not pay attention; he has no time for that.(Respondent 14)

When told of my diagnosis, I was confused at first after a long period of not knowing what it was. I did not accept it quite well because of how they informed me. It was as if I would die soon, the manner of approach was not good, but I still survived in those hopeless conditions.(Respondent 17)

I really wish to get more information because I do not have any experience with cancer. It was the first time when I was diagnosed.(Respondent 14)

3.4. Unclear Health Professional Roles and Responsibilities

I wouldn’t say much because we would get different doctors whenever we went to hospital A. After all, whenever we went there, we would find maybe another doctor at that particular time.(Respondent 15)

I will be telling lies if I say there was someone who explained which doctor was going to do what and which doctor would do what. There you find doctors doing their rounds, coming to you as a team, and one doctor would explain to the rest of the team about your condition for them to know but not that they discuss with me as a patient.(Respondent 5)

3.5. Unmet Supportive Care Needs

I am forced to wake up very early at midnight so that I can prepare and get ready to catch the first taxi by 04:30 a.m. because the hospital can get packed. We live far from the hospitals, so we are forced to wake up so early in the dark to catch public transport. From home, I take a taxi to town, and there again I take another taxi to the hospital, and when you get there, you hold the queue. Sometimes the appointment date comes when I don’t have money for transport, I would then knock door to door, borrowing transport money from neighbors to manage to save my life.(Respondent 12)

Hospital C told me to phone them whenever I face any difficulties, but I can’t even phone them because I usually don’t have airtime. I would have called them to report that my burning, swollen feet and bones can be so painful as if someone had been lashing me. So, I just report all the matters when I get there on my appointment date, but I cannot call because of airtime.(Respondent 10)

3.6. Opportunities for Improved Care Coordination

The patient would still be shocked that he is diagnosed with cancer, and cancer is a severe illness, despite the availability of chemo and radiation therapy. However, you are still under the shock that you might die soon. So, I would advise that they [the healthcare providers] allocate a nurse or someone who will stimulate the mindset of the patients and give them hope that even though they are cancer patients, it does not mean that they will die soon.(Respondent 12)

There wasn’t any specific individual that we would say has been assigned to him [patient] that will be a coordinator between ourselves and them [healthcare providers] whenever we go there [healthcare facilities]. Even that could be a good idea if a patient could have a contact person that you know when you have this, you could call.(Respondent 20: Proxy)

So that whenever I see something that might be developing, I would be able to contact that person for awareness even before the appointment date.(Respondent 8)

Mainly, if we could have community support groups, which maybe could be led by retired nurses, other people maybe are retired who could be trained to understand what kind of questions and how are cancer patients different from other patients, be trained to even visit a family once in a while.(Respondent 9)

I want to emphasize the need for a social worker, because this [cancer] is between life and death, and I think they should have them on offer while it is still early. Understand that when the patient is diagnosed, they need that support, because so many things happen, so it should be readily available. My father still needs that support service, and we are struggling. They did not link us with anything or anyone.(Respondent 3: Proxy)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMSF: | Bristol–Myers Squibb Foundation |

| CIDERU: | Cancer & Infectious Diseases Epidemiology Research Unit |

| DBN: | Durban |

| GT: | Grounded theory |

| HICs: | High-income countries |

| IALCH: | Inkosi Albert Luthuli Central Hospital |

| KZN: | KwaZulu-Natal |

| LMICs: | Low- and middle-income counties |

| MLCCP: | Multinational Lung Cancer Control Programme |

| PMB: | Pietermaritzburg |

| SA: | South Africa |

| UKZN: | University of KwaZulu-Natal |

| WHO: | World Health Organization |

References

- The National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD). Cancer in South Africa; The National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD): Tokyo, Japan, 2014.

- Aberg, L.; Albrecht, B.; Rudolph, T. How health systems can improve value in cancer care. Health Int. 2012, 27, 1531–1538. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, J.; Kannampallil, T.; Patel, V. Bridging Gaps in Handoffs: A Continuity of Care based Approach. J. Biomed. Inform. 2011, 45, 240–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Care Coordination; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2018.

- Association, A.M. Management of Chronic Disease; Department of Health and Aged Care: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2004.

- Bickell, N.A.; Young, G.J. Coordination of care for early-stage breast cancer patients. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 737–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouwers, M.C.; Vukmirovic, M.; Tomasone, J.R.; Grunfeld, E.; Urquhart, R.; O’Brien, M.A.; Walker, M.; Webster, F.; Fitch, M. Documenting coordination of cancer care between primary care providers and oncology specialists in Canada. Can. Fam. Physician 2016, 62, e616–e625. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cancer Support Community. Access to Care in Cancer 2016: Barriers and Challenges; Research and Training Institute: Washington DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, J.K.; Humiston, S.G.; Meldrum, S.C.; Salamone, C.M.; Jean-Pierre, P.; Epstein, R.M.; Fiscella, K. Patients’ experiences with navigation for cancer care. Patient Educ. Couns. 2010, 80, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavarri-Guerra, Y.; Soto-Perez-de-Celis, E.; Ramos-López, W.; San Miguel de Majors, S.L.; Sanchez-Gonzalez, J.; Ahumada-Tamayo, S.; Viramontes-Aguilar, L.; Sanchez-Gutierrez, O.; Davila-Davila, B.; Rojo-Castillo, P. Patient navigation to enhance access to care for underserved patients with a suspicion or diagnosis of cancer. Oncologist 2019, 24, 1195–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, E. Preparing Patients and Caregivers to Participate in Care Delivered Across Settings: The Care Transitions Intervention. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2004, 52, 1817–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubuzo, B.; Ginindza, T.; Hlongwana, K. Exploring barriers to lung cancer patient access, diagnosis, referral and treatment in Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa: The health providers’ perspectives. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2019, 8, 380–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, E.M.; Pineda, N.; Lonhart, J.; Davies, S.M.; McDonald, K.M. A systematic review of the care coordination measurement landscape. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.C.; Kayamba, V.; Peek, R.M., Jr.; Heimburger, D. Cancer Control in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Is It Time to Consider Screening? J. Glob. Oncol. 2019, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tho, P.C.; Ang, E. The effectiveness of patient navigation programs for adult cancer patients undergoing treatment: A systematic review. JBI Evid. Synth. 2016, 14, 295–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urman, A.; Josyula, S.; Rosenberg, A.; Lounsbury, D.; Rohan, T.; Hosgood, D. Burden of Lung Cancer and Associated Risk Factors in Africa by Region. J. Pulm. Respir. Med. 2016, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, S.J.; Jacobsen, P.B. Cancer care coordination: Opportunities for healthcare delivery research. Transl. Behav. Med. 2018, 8, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Guide to Cancer Early Diagnosis; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Donelan, K.; Mailhot, J.R.; Dutwin, D.; Barnicle, K.; Oo, S.A.; Hobrecker, K.; Percac-Lima, S.; Chabner, B.A. Patient perspectives of clinical care and patient navigation in follow-up of abnormal mammography. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2011, 26, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadori, D.; Serra, P.; Bucchi, L.; Altini, M.; Majinge, C.; Kahima, J.; Botteghi, M.; John, C.; Stefan, D.C.; Masalu, N. The Mwanza Cancer Project. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 146–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balogh, E.P.; Ganz, P.A.; Murphy, S.B.; Nass, S.J.; Ferrell, B.R.; Stovall, E. Patient-centered cancer treatment planning: Improving the quality of oncology care. Summary of an Institute of Medicine workshop. Oncologist 2011, 16, 1800–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Man, Y.; Atsma, F.; Oosterveld-Vlug, M.G.; Brom, L.; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B.D.; Westert, G.P.; Groenewoud, A.S. The Intensity of Hospital Care Utilization by Dutch Patients With Lung or Colorectal Cancer in their Final Months of Life. Cancer Control 2019, 26, 1073274819846574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Health & Human Services. Linking Cancer Care; Victorian Government Department of Human Services: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2007.

- Edwards, L.B.; Greeff, L.E. Exploring grassroots feedback about cancer challenges in South Africa: A discussion of themes derived from content thematic analysis of 316 photo-narratives. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2017, 28, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hlongwana, K.; Lubuzo, B.; Mlaba, P.; Zondo, S.; Ginindza, T. Multistakeholder Experiences of Providing, Receiving, and Setting Priorities for Lung Cancer Care in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2020, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klabunde, C.N.; Han, P.K.; Earle, C.C.; Smith, T.; Ayanian, J.Z.; Lee, R.; Ambs, A.; Rowland, J.H.; Potosky, A.L. Physician roles in the cancer-related follow-up care of cancer survivors. Fam. Med. 2013, 45, 463. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chumbler, N.R.; Mkanta, W.N.; Richardson, L.C.; Harris, L.; Darkins, A.; Kobb, R.; Ryan, P. Remote patient-provider communication and quality of life: Empirical test of a dialogic model of cancer care. J. Telemed. Telecare 2007, 13, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hack, T.F.; Degner, L.F.; Parker, P.A. The communication goals and needs of cancer patients: A review. Psychooncology 2005, 14, 831–845; discussion 846–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momberg, M.; Botha, M.H.; Van der Merwe, F.H.; Moodley, J. Women’s experiences with cervical cancer screening in a colposcopy referral clinic in Cape Town, South Africa: A qualitative analysis. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e013914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Daniel, M.; Rosenstein, A.H. Professional communication and team collaboration. In Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US): Rockville, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sada, Y.; Street, R.L., Jr.; Singh, H.; Shada, R.; Naik, A.D. Primary care and communication in shared cancer care: A qualitative study. Am. J. Manag. Care 2011, 17, 259. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Santoso, J.T.; Engle, D.B.; Schaffer, L.; Wan, J.Y. Cancer diagnosis and treatment: Communication accuracy between patients and their physicians. Cancer J. 2006, 12, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starfield, B.H.; Simborg, D.W.; Horn, S.D.; Yourtee, S.A. Continuity and coordination in primary care: Their achievement and utility. Med. Care 1976, 14, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sussman, J.; Baldwin, L.M. The interface of primary and oncology specialty care: From diagnosis through primary treatment. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2010, 2010, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutcliffe, K.M.; Lewton, E.; Rosenthal, M.M. Communication failures: An insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad. Med. 2004, 79, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.; Young, J.M.; Harrison, J.D.; Butow, P.N.; Solomon, M.J.; Masya, L.; White, K. What is important in cancer care coordination? A qualitative investigation. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2011, 20, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, K.J.; Meiser, B.; Zilliacus, E.; Kaur, R.; Taouk, M.; Girgis, A.; Butow, P.; Goldstein, D.; Hale, S.; Perry, A.; et al. Communicating with patients from minority backgrounds: Individual challenges experienced by oncology health professionals. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2017, 26, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, M.A.; DiazGranados, D.; Dietz, A.S.; Benishek, L.E.; Thompson, D.; Pronovost, P.J.; Weaver, S.J. Teamwork in healthcare: Key discoveries enabling safer, high-quality care. Am. Psychol. 2018, 73, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ethridge, P.; Lamb, G.S. Professional nursing case management improves quality, access and costs. Nurs. Manag. 1989, 20, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, K.M.; Sundaram, V.; Bravata, D.M.; Lewis, R.; Lin, N.; Kraft, S.A.; McKinnon, M.; Paguntalan, H.; Owens, D.K. Closing the Quality Gap: A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategies (Vol. 7: Care Coordination); Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US): Rockville, MD, USA, 2007.

- Schmitt, M.H. Collaboration improves the quality of care: Methodological challenges and evidence from US health care research. J. Interprof. Care 2001, 15, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.; Jones, L.; Richardson, A.; Murad, S.; Irving, A.; Aslett, H.; Ramsay, A.; Coelho, H.; Andreou, P.; Tookman, A. The relationship between patients’ experiences of continuity of cancer care and health outcomes: A mixed methods study. Br. J. Cancer 2008, 98, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schang, L.; Waibel, S.; Thomson, S. Measuring Care Coordination: Health System and Patient Perspectives: Report Prepared for the Main Association of Austrian Social Security Institutions; LSE Health: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yates, P. Achieving coordinated cancer care: Report on the Clinical Oncological Society of Australia care coordination workshop. Cancer Forum 2007, 31, 169–172. [Google Scholar]

- Aiello Bowles, E.J.; Tuzzio, L.; Wiese, C.J.; Kirlin, B.; Greene, S.M.; Clauser, S.B.; Wagner, E.H. Understanding high-quality cancer care: A summary of expert perspectives. Cancer 2008, 112, 934–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanchard, C.; Lubuzo, B.; Asirwa, F.C.; Dlamini, X.; Msadabwe-Chikuni, S.C.; Mwachiro, M.; Shyirambere, C.; Ruhangaza, D.; Milner, D.A., Jr.; Van Loon, K. Multisector Collaborations and Global Oncology: The Only Way Forward. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2021, 7, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubuzo, B.; Hlongwana, K.; Ginindza, T. Cancer care reform in South Africa: A case for cancer care coordination: A narrative review. Palliat. Support. Care 2021, 20, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubuzo, B.; Hlongwana, K.W.; Ginindza, T.G. Improving Timely Access to Diagnostic and Treatment Services for Lung Cancer Patients in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: Priority-Setting through Nominal Group Techniques. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, M.; Holzman, E.; Erwin, E.; Michelen, S.; Rositch, A.F.; Kumar, S.; Vanderpuye, V.; Yeates, K.; Liebermann, E.J.; Ginsburg, O. Patient navigation services for cancer care in low-and middle-income countries: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, H.P. Patient navigation: A community centered approach to reducing cancer mortality. J. Cancer Educ. 2006, 21, S11–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, H.P. The origin, evolution, and principles of patient navigation. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2012, 21, 1614–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, H.P.; Rodriguez, R.L. History and principles of patient navigation. Cancer 2011, 117, 3539–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freund, K.M. Implementation of evidence-based patient navigation programs. Acta Oncol. 2017, 56, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, S.A.; Chambers, D.A. Leveraging implementation science to improve cancer care delivery and patient outcomes. J. Oncol. Pract. 2017, 13, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koczwara, B. Cancer and Chronic Conditions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia, T.A.; Gunn, C.M.; Bak, S.M.; Flacks, J.; Nelson, K.P.; Wang, N.; Ko, N.Y.; Morton, S.J. Patient navigation to address sociolegal barriers for patients with cancer: A comparative-effectiveness study. Cancer 2022, 128, 2623–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis-Thames, M.W.; Tom, L.S.; Leung, I.S.; Yang, A.; Simon, M.A. An examination of the implementation of a patient navigation program to improve breast and cervical cancer screening rates of Chinese immigrant women: A qualitative study. BMC Womens Health 2022, 22, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mboineki, J.F.; Wang, P.; Dhakal, K.; Getu, M.A.; Chen, C. The Effect of Peer-Led Navigation Approach as a Form of Task Shifting in Promoting Cervical Cancer Screening Knowledge, Intention, and Practices Among Urban Women in Tanzania: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Cancer Control 2022, 29, 10732748221089480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, J.; Ahn, S. Effects of Nurse Navigators During the Transition from Cancer Screening to the First Treatment Phase: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Asian Nurs. Res. Korean Soc. Nurs. Sci. 2021, 15, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.L.; Schneider, F.; Kalinke, L.P.; Kempfer, S.S.; Backes, V.M.S. Clinical outcomes of patient navigation performed by nurses in the oncology setting: An integrative review. Rev. Bras. Enferm 2021, 74, e20190804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamez-Salazar, J.; Mireles-Aguilar, T.; de la Garza-Ramos, C.; Garcia-Garcia, M.; Ferrigno, A.S.; Platas, A.; Villarreal-Garza, C. Prioritization of Patients with Abnormal Breast Findings in the Alerta Rosa Navigation Program to Reduce Diagnostic Delays. Oncologist 2020, 25, 1047–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubuzo, B.; Hlongwana, K.W.; Hlongwa, M.; Ginindza, T.G. Coordination Models for Cancer Care in Low-and Middle-Income Countries: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannigan, B.; Simpson, A.; Coffey, M.; Barlow, S.; Jones, A. Care coordination as imagined, care coordination as done: Findings from a cross-national mental health systems study. Int. J. Integr. Care 2018, 18, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrillo, J.E.; Carrillo, V.A.; Perez, H.R.; Salas-Lopez, D.; Natale-Pereira, A.; Byron, A.T. Defining and targeting health care access barriers. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2011, 22, 562–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, J.; Garvey, G.; Valery, P.C.; Ball, D.; Fong, K.M.; Vinod, S.; O’Connell, D.L.; Chambers, S.K. Barriers to lung cancer care: Health professionals’ perspectives. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 25, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, B.; Ir, P.; Bigdeli, M.; Annear, P.L.; Van Damme, W. Addressing access barriers to health services: An analytical framework for selecting appropriate interventions in low-income Asian countries. Health Policy Plan. 2012, 27, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joffe, M.; Ayeni, O.; Norris, S.A.; McCormack, V.A.; Ruff, P.; Das, I.; Neugut, A.I.; Jacobson, J.S.; Cubasch, H. Barriers to early presentation of breast cancer among women in Soweto, South Africa. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubuzo, B.; Ginindza, T.; Hlongwana, K. The barriers to initiating lung cancer care in low-and middle-income countries. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2020, 35, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheppers, E.; van Dongen, E.; Dekker, J.; Geertzen, J.; Dekker, J. Potential barriers to the use of health services among ethnic minorities: A review. Fam. Pract. 2006, 23, 325–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, J.; Harrison, J.D.; Young, J.M.; Butow, P.N.; Solomon, M.J.; Masya, L. What are the current barriers to effective cancer care coordination? A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2010, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton, L.; McNeill, R.; Stevens, W.; Murray, M.; Lewis, C.; Aitken, D.; Garrett, J. Patient perceptions of barriers to the early diagnosis of lung cancer and advice for health service improvement. Fam. Pract. 2013, 30, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zondo, S. The extrinsic factors affecting patient access, referral and treatment of lung cancer in selected oncology public health facilities in KwaZulu-Natal. Healthc. Low-Resour. Settings 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Haig, B. Grounded theory as scientific method. In The Philosophy of Education’s 1995 Yearbook; Neiman, A., Ed.; Philosophy of Education Society: Champaign, IL, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa. General Household Survey 2021; Africa, S.S., Ed.; Statistics South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2022; pp. 23–25.

- Jobson, M. Structure of the Health System in South Africa; Khulumani Support Group: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sedgwick, P. Snowball sampling. BMJ 2013, 347, f7511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, E.R.; Litt, M.; Dunn, L.B.; Wimer, J. Proxy consent to research: The legal landscape. Yale J. Health Policy Law Ethics 2008, 8, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Mourad, M.; Bousleiman, S.; Wapner, R.; Gyamfi-Bannerman, C. Conducting research during the COVID-19 pandemic. Semin. Perinatol. 2020, 44, 151287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilal, A.H.; Alabri, S.S. Using NVivo for data analysis in qualitative research. Int. Interdiscip. J. Educ. 2013, 2, 181–186. [Google Scholar]

- Chun Tie, Y.; Birks, M.; Francis, K. Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers. SAGE Open Med. 2019, 7, 2050312118822927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis; SAGE: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory—Strategies for Qualitative Research (Reimpressão ed.); Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, S.M. Grounded theory and the constant comparative method: Valid research strategies for educators. J. Emerg. Trends Educ. Res. Policy Stud. 2012, 3, 83–86. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, R.S.; Stern, P.N. Using Grounded Theory in Nursing; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Birks, M.; Mills, J. Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide; SAGE: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bitsch, V. Qualitative research: A grounded theory example and evaluation criteria. J. Agribus. 2005, 23, 75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, A.; Charmaz, K. The Sage Handbook of Grounded Theory; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine de Gruyter: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Lingard, L.; Albert, M.; Levinson, W. Grounded theory, mixed methods, and action research. BMJ 2008, 337, a567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreps, G.L.; Arora, N.K.; Nelson, D.E. Consumer/provider communication research: Directions for development. Patient Educ. Couns. 2003, 50, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.; Schore, J.; Archibald, N.; Chen, A.; Peikes, D.; Sautter, K.; Aliotta, S.; Ensor, T. Coordinating Care for Medicare Beneficiaries: Early Experiences of 15 Demonstration Programs, Their Patients, and Providers; Mathematica Policy Research: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mazor, K.M.; Beard, R.L.; Alexander, G.L.; Arora, N.K.; Firneno, C.; Gaglio, B.; Greene, S.M.; Lemay, C.A.; Robinson, B.E.; Roblin, D.W. Patients’ and family members’ views on patient-centered communication during cancer care. Psychooncology 2013, 22, 2487–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreps, G.L.; O’HAIR, D.; Clowers, M. The influences of human communication on health outcomes. Am. Behav. Sci. 1994, 38, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreps, G.L. The impact of communication on cancer risk, incidence, morbidity, mortality, and quality of life. Health Commun. 2003, 15, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seek, A.J.; Hogle, W.P. Modeling a better way: Navigating the healthcare system for patients with lung cancer. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2007, 11, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foerster, M.; Anderson, B.O.; McKenzie, F.; Galukande, M.; Anele, A.; Adisa, C.; Zietsman, A.; Schuz, J.; dos Santos Silva, I.; McCormack, V. Inequities in breast cancer treatment in sub-Saharan Africa: Findings from a prospective multi-country observational study. Breast Cancer Res. 2019, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.; Lao, X.Q.; Ho, K.-F.; Goggins, W.B.; Tse, S.L. Incidence and mortality of lung cancer: Global trends and association with socioeconomic status. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Continuity and Coordination of Care: A Practice Brief to Support Implementation of the WHO Framework on Integrated People-Centred Health Services; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Allison, A.L.; Ishihara-Wong, D.D.; Domingo, J.B.; Nishioka, J.; Wilburn, A.; Tsark, J.U.; Braun, K.L. Helping cancer patients across the care continuum: The navigation program at the Queen’s Medical Center. Hawaii J. Med. Public Health 2013, 72, 116–121. [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia, T.A.; Darnell, J.S.; Ko, N.; Snyder, F.; Paskett, E.D.; Wells, K.J.; Whitley, E.M.; Griggs, J.J.; Karnad, A.; Young, H.; et al. The impact of patient navigation on the delivery of diagnostic breast cancer care in the National Patient Navigation Research Program: A prospective meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2016, 158, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischof, J.J.; Sellers, J.B.; Phillips, A.W.; Petrongelli, J.J.; Stuckey, A.E.; Platts-Mills, T.F. Patient navigation for complex care patients in the emergency department: A survey of oncology patient navigators. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 4359–4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukowski, A.; Chávarri-Guerra, Y.; Goss, P.E. The Potential Role of Patient Navigation in Low- and Middle-Income Countries for Patients With Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 994–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| # | Sex | Age | Type of Participant | Marital Status | Educational Level | Employment Status | Geographic Location | Disease Staging | Treatment (Tx) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 70s | Proxy | Widowed | High school | Pensioner | Urban | 4 | Refused Tx |

| 2 | M | 70s | Patient | Married | Primary school | Pensioner | Urban | 4 | Chemotherapy |

| 3 | M | 30s | Proxy | Single | High school | Unemployed | Township | - | Chemotherapy |

| 4 | M | 60s | Patient | Married | Secondary school | Unemployed | Township | 4 | Chemotherapy |

| 5 | M | 60s | Patient | Single | No school | Unemployed | Township | 4 | Not initiated |

| 6 | M | 70s | Patient | Married | High school | Pensioner | Township | 4 | Not initiated |

| 7 | M | 60s | Patient | Married | Primary school | Unemployed | Township | 4 | Chemotherapy |

| 8 | M | 60s | Patient | Married | High school | Unemployed | Township | - | Chemotherapy |

| 9 | M | 60s | Patient | Married | Not shared | Unemployed | Township | - | Chemotherapy |

| 10 | M | 50s | Patient | Married | Primary school | Unemployed | Township | - | Chemotherapy |

| 11 | M | 30s | Patient | Single | Primary school | Unemployed | Township | 4 | Chemotherapy |

| 12 | M | 50s | Patient | Married | High school | Unemployed | Rural | - | Chemotherapy |

| 13 | M | 60s | Patient | Single | Secondary school | Pensioner | Township | - | Chemotherapy |

| 14 | M | 30s | Patient | Single | High school | Unemployed | Rural | - | Chemotherapy |

| 15 | M | 50s | Patient | Married | Not shared | Unemployed | Urban | 4 | Chemotherapy |

| 16 | M | 70s | Proxy | Married | Tertiary | Retired | Urban | - | Chemotherapy |

| 17 | F | 20s | Patient | Single | High school | Unemployed | Rural | 4 | Chemotherapy |

| 18 | M | 40s | Proxy | Single | Primary school | Unemployed | Rural | 4 | Chemotherapy |

| 19 | M | 60s | Patient | Married | High school | Pensioner | Urban | 4 | Chemotherapy |

| 20 | F | 30s | Proxy | Single | Tertiary | Unemployed | Rural | 4 | Not sure |

| 21 | F | 40s | Proxy | Widowed | High school | Unemployed | Township | 4 | Chemotherapy |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lubuzo, B.; Hlongwana, K.W.; Ginindza, T.G. Lung Cancer Patients’ Conceptualization of Care Coordination in Selected Public Health Facilities of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13871. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113871

Lubuzo B, Hlongwana KW, Ginindza TG. Lung Cancer Patients’ Conceptualization of Care Coordination in Selected Public Health Facilities of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(21):13871. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113871

Chicago/Turabian StyleLubuzo, Buhle, Khumbulani W. Hlongwana, and Themba G. Ginindza. 2022. "Lung Cancer Patients’ Conceptualization of Care Coordination in Selected Public Health Facilities of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 21: 13871. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113871

APA StyleLubuzo, B., Hlongwana, K. W., & Ginindza, T. G. (2022). Lung Cancer Patients’ Conceptualization of Care Coordination in Selected Public Health Facilities of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 13871. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113871