The Impact of Mobile Payment on Household Poverty Vulnerability: A Study Based on CHFS2017 in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Research Hypothesis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Source

3.2. Variable Measurement

3.2.1. Explained Variables

3.2.2. Core Explanatory Variable

3.2.3. Other Control Variables

3.3. Model, Variable Processing, and Description

3.4. Identifying Strategy and Estimation Method

4. Results

4.1. Baseline Analysis

4.2. Robustness Check

4.3. Mechanism Analysis

4.3.1. The Role of Entrepreneurial Decision-Making

4.3.2. The Role of Risk Management Capabilities

4.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.4.1. Population Differences

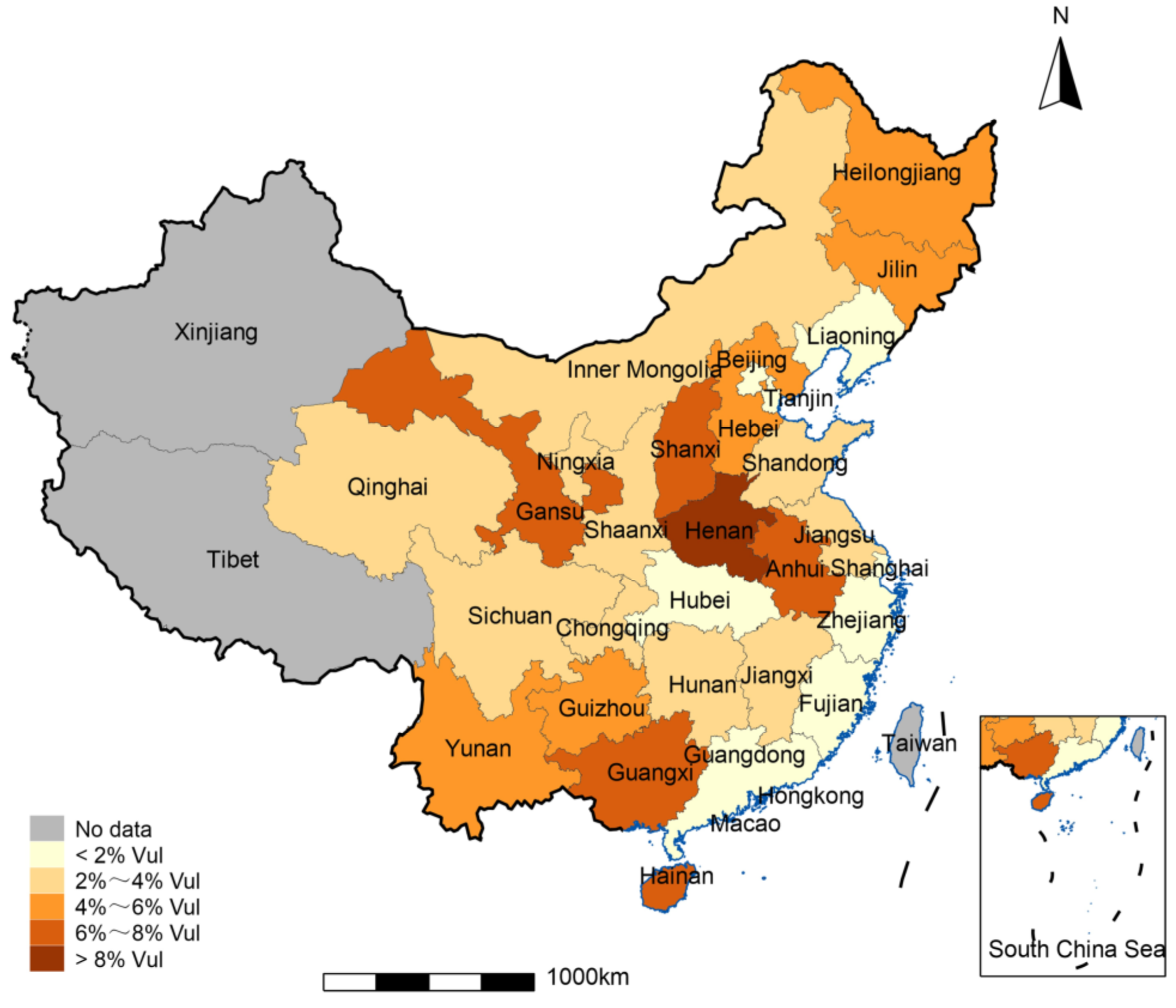

4.4.2. Regional Differences

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2022-02/22/content_5675035.htm (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Available online: http://rmfp.people.com.cn/n1/2020/0817/c406725-31824372.html (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Jeanneney, S.G.; Kpodar, K. Financial Development and Poverty Reduction: Can There Be a Benefit Without a Cost? J. Dev. Stud. 2011, 47, 143–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Pamuk, H.; Ramrattan, R.; Uras, B.R. Payment Instruments, Finance and Development. J. Dev. Econ. 2018, 133, 162–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korenman, S.D. Including Health Insurance in Poverty Measurement: The Impact of Massachusetts Health Reform on Poverty. J. Health Econ. 2016, 9, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pega, F.; Gilsanz, P.; Kawachi, I.; Wilson, N.; Blakely, T. Cumulative Receipt of an Anti-Poverty Tax Credit for Families Did Not Impact Tobacco Smoking among Parents. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 179, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, M.; Jumare, H.; Brick, K. Risk Preferences and Poverty Traps in the Uptake of Credit and Insurance amongst Small-Scale Farmers in South Africa. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2020, 180, 826–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Li, J.; Fang, X.; Wei, H. The Mechanism and Validation of Digital Inclusive Finance Promoting Inclusive Growth. Stat. Res. 2021, 38, 62–75. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, S.; Daly, K.J. Finance and Poverty: Evidence from Fixed Effect Vector Decomposition. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2009, 10, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, K.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F.; Zhao, J. How Inclusive Financial Development Eradicates Energy Poverty in China? The Role of Technological Innovation. Energy Econ. 2022, 109, 106007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, X. Stakeholders Strategies in Poverty Alleviation and Clean Energy Access: A Case Study of China’s PV Poverty Alleviation Program. Energy Policy 2019, 135, 111011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, B.M. Income Inequality, Poverty, and the Liquidity of Stock Markets. J. Dev. Econ. 2018, 130, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, R.P.; Arvin, M.B.; Nair, M.S.; Hall, J.H.; Bennett, S.E. Sustainable Economic Development in India: The Dynamics between Financial Inclusion, ICT Development, and Economic Growth. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 169, 120758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyekum, F.K.; Reddy, K.; Wallace, D.; Wellalage, N.H. Does Technological Inclusion Promote Financial Inclusion among SMEs? Evidence from South-East Asian (SEA) Countries. Glob. Financ. J. 2022, 53, 100618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewa Wellalage, N.; Hunjra, A.I.; Manita, R.; Locke, S.M. Information Communication Technology and Financial Inclusion of Innovative Entrepreneurs. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 163, 120416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Nie, L.; Sun, H.; Sun, W.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. Digital Finance, Green Technological Innovation and Energy-Environmental Performance: Evidence from China’s Regional Economies. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 327, 129458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Guo, J. Impacts of Digital Inclusive Finance on CO2 Emissions from a Spatial Perspective: Evidence from 272 Cities in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 355, 131618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Musibau, H.O.; Genç, S.Y.; Shaheen, R.; Ameen, A.; Tan, Z. Digitalization of Economy Is the Key Factor behind Fourth Industrial Revolution: How G7 Countries Are Overcoming with the Financing Issues? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 165, 120533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B.S. Can Financial Technology Innovate Benefit Distribution in Payments for Ecosystem Services and REDD+? Ecol. Econ. 2017, 139, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, P.N.; Fox, C.A.; Kelley, E.K. To Own or Not to Own: Stock Loans around Dividend Payments. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 140, 539–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkijika, S.F. An Affective Response Model for Understanding the Acceptance of Mobile Payment Systems. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2020, 39, 100905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yan, W.; Hu, B. Resistance to Facial Recognition Payment in China: The Influence of Privacy-Related Factors. Telecommun. Policy 2021, 45, 102155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koomson, I.; Bukari, C.; Villano, R.A. Mobile Money Adoption and Response to Idiosyncratic Shocks: Empirics from Five Selected Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 167, 120728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostad, W.L.; Klevens, J.; Ports, K.A.; Ford, D.C. Impact of the United States Federal Child Tax Credit on Childhood Injuries and Behavior Problems. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 109, 104718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, J.; Križ, K.; Edin, K.; Halpern-Meekin, S. Dignity and Dreams: What the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) Means to Low-Income Families. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2015, 80, 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisner, B.; Blaikie, P.; Cannon, T.; Davis, I. AT RISK: Natural Hazards, People’s Vulnerability and Disasters; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 1994; ISBN 978-0-203-44423-8. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, N.W. Impacts of Disasters and Disaster Risk Management in Malaysia: The Case of Floods. In Resilience and Recovery in Asian Disasters; Aldrich, D.P., Oum, S., Sawada, Y., Eds.; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2015; pp. 239–265. ISBN 978-4-431-55021-1. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, M.A.; Schoon, M.L.; Ke, W.; Börner, K. Scholarly Networks on Resilience, Vulnerability and Adaptation within the Human Dimensions of Global Environmental Change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebow, E.B. At Risk: Natural Hazards, People’s Vulnerability, and Disasters. J. Homel. Secur. Emerg. Manag. 2005, 2, 1547–7355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Han, X. Sustainable Poverty Reduction Effect of Digital Finance: A Perspective of Household Poverty Vulnerability. Chin. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2021, 13, 57–77+119. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri, S. Assessing Household Vulnerability to Poverty from Cross-Sectional Data: A Methodology and Estimates from Indonesia; Department of Economics, Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, I.; Harttgen, K. Estimating Households Vulnerability to Idiosyncratic and Covariate Shocks: A Novel Method Applied in Madagascar. World Dev. 2009, 37, 1222–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L. New progress in poverty vulnerability theory and policy research. Econ. Perspect. 2017, 06, 96–108. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Magrini, E.; Montalbano, P.; Winters, L.A. Households’ Vulnerability from Trade in Vietnam. World Dev. 2018, 112, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayadunne, S.; Park, S. An Economic Model to Evaluate Information Security Investment of Risk-Taking Small and Medium Enterprises. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 182, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, M.M.; Mugera, A.W.; Schilizzi, S.; Siddique, K.H.M. An Assessment of Vulnerability to Poverty in Punjab, Pakistan: Subjective Choices of Poverty Indicators. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 134, 117–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senapati, A.K. Assessing the Vulnerability of Agricultural Households to Covariate and Idiosyncratic Shocks: A Case Study in Odisha, India. Clim. Dev. 2020, 12, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Zhang, D. Financial Inclusion, Household Poverty and Vulnerability. China Econ. Q. 2020, 20, 153–172. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celidoni, M. Vulnerability to Poverty: An Empirical Comparison of Alternative Measures. Appl. Econ. 2013, 45, 1493–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiwaula, L.S.; Witt, R.; Waibel, H. An Asset-Based Approach to Vulnerability: The Case of Small-Scale Fishing Areas in Cameroon and Nigeria. J. Dev. Stud. 2011, 47, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zheng, W.; Jia, R.; Jing, P. Health Insurance, Health Heterogeneity, and Targeted Poverty Reduction: A Vulnerability to Poverty Approach. J. Financ. Res. 2019, 5, 56–75. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Z.; Zhou, W. From Anti-poverty Campaign to Common Prosperity: Dynamic Identification of Relative Poverty and Quantitative Decomposition of Poverty Changes in China. China Ind. Econ. 2021, 10, 59–77. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemu, B.T.; Singh, S.P. How Does Multidimensional Rural Poverty Vary across Agro-Ecologies in Rural Ethiopia? Evidence from the Three Districts. J. Poverty 2021, 25, 480–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchett, L.; Suryahadi, A.; Sumarto, S. Quantifying Vulnerability to Poverty: A Proposed Measure, with Application to Indonesia; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; p. 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klasen, S.; Waibel, H. Vulnerability to Poverty in South-East Asia: Drivers, Measurement, Responses, and Policy Issues. World Dev. 2015, 71, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, L. Does Family Education Expenditure Reduce the Household’s Poverty Vulnerability in Rural China? An Empirical Study Based on CFPS Data. J. Financ. Econ. 2019, 45, 32–44. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.; Wu, T.; Xue, P. Can Mobile Payment Increase Household Income and Mitigate the Lower Income Condition Caused by Health Risks? Evidence from Rural China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.-Y.; Chen, D.C. Consumers’ Switching from Cash to Mobile Payment under the Fear of COVID-19 in Taiwan. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, T.; Jack, W. The Long-Run Poverty and Gender Impacts of Mobile Money. Science 2016, 354, 1288–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikulwe, E.M.; Fischer, E.; Qaim, M. Mobile Money, Smallholder Farmers, and Household Welfare in Kenya. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e109804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Li, X.; Li, W. The Nexus between Credit Channels and Farm Household Vulnerability to Poverty: Evidence from Rural China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fu, Y. Digital Financial Inclusion and Vulnerability to Poverty: Evidence from Chinese Rural Households. CAER 2022, 14, 64–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zameer, H.; Shahbaz, M.; Vo, X.V. Reinforcing Poverty Alleviation Efficiency through Technological Innovation, Globalization, and Financial Development. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 161, 120326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandurra, G.; Thomas, A.; Passaro, R.; Bencini, J.; Carfora, A. Does Climate Finance Reduce Vulnerability in Small Island Developing States? An Empirical Investigation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Shen, Y.; Sun, A. Evaluating the Stimulus Effect of Consumption Vouchers in China. Econ. Res. J. 2020, 55, 4–20. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, T.; Wang, C.; Wan, G. Digital Finance and Household Consumption: Theory and Evidence from China. Manag. World 2020, 36, 48–63. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutter, C.; Bruton, G.D.; Chen, J. Entrepreneurship as a Solution to Extreme Poverty: A Review and Future Research Directions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.C.; Martinez–Perez, A.; Kedir, A.M. Informal Entrepreneurship in Developing Economies: The Impacts of Starting up Unregistered on Firm Performance. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 41, 773–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Kan, B. On the Effect of Internet Finance on Profitability of Commercial Banks. Financ. Econ. 2021, 2, 14–24. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. Mobile Payment and Informal Business: Evidence from China’s Household Panel Data. China World Econ. 2020, 28, 90–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Gong, X. Mobile Payment and Rural Household Consumption: Evidence from China. Telecommun. Policy 2022, 46, 102276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Wu, Y.; Guo, J. Mobile Payment and Chinese Rural Household Consumption. China Econ. Rev. 2022, 71, 101719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Gong, X.; Guo, P. The Impact of Mobile Payment on Entrepreneurship Micro Evidence from China Household Finance Survey. China Ind. Econ. 2019, 3, 119–137. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.; Yin, Z.; Jia, N.; Xu, S.; Ma, S.; Zheng, L. Data You Need to Know about China; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; ISBN 978-3-642-38150-8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Liu, W. Research on the Alleviation Effect of “Single-person Households” Enrollment on the Poverty Vulnerability of Low-income Groups-An Empirical Analysis Based on CFPS Data. Inq. Econ. Issues 2022, 4, 55–78. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Song, Q.; Wu, Y.; Yin, Z. Impact of financial literacy on the survival of entrepreneurship. Sci. Res. Manag. 2020, 41, 133–142. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrea, M.A.; Maldonado, J.H. Vulnerability and Risk Management: The Importance of Financial Inclusion for Beneficiaries of Conditional Transfers in Colombia. Can. J. Dev. Stud./Rev. Can. D’études Du Développement 2011, 32, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Year | Viewpoints | Critical Analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First aspect | Qiu et al., 2022 [47] | Mobile payment can increase rural household income and reduce the health risks of family members | The data need to be further improved |

| Yu et al., 2022 [48] | Using mobile payment helps reduce COVID-19 infection | The impact of the external institutional environment on mobile payment remains to be discussed | |

| Suri et al., 2016 [49] | Mobile payment can lift households out of poverty and increase their consumption | The universality of mobile payment for vulnerable groups is not explained from the perspective of dynamic poverty | |

| Kikulwe et al., 2014 [50] | Mobile payment can help to overcome some of the important smallholder market access constraints that obstruct rural development and poverty reduction | The impact mechanism of mobile payment on informal savings and insurance needs to be explored | |

| Second aspect | Sun et al., 2020 [51] | Credit can reduce vulnerability to poverty | The mechanism of credit channels on poverty vulnerability remains to be explored |

| Wang et al., 2022 [52] | Digital finance can reduce poverty vulnerability | The influence mechanism between the two needs to be explored | |

| Zameer et al., 2020 [53] | Financial development positively contributes to poverty alleviation efficiency in China | Not considered from the perspective of dynamic poverty | |

| Scandurra et al., 2020 [54] | External funds can reduce the vulnerability of small island developing states | The estimation is biased because the political purpose of external funds is not taken into account |

| Variable | Definition |

|---|---|

| Mobile payment | Using mobile payment: 1, otherwise: 0 |

| VEP1 | USD 1.9 poverty line, 29% vulnerability line |

| VEP2 | USD 1.9 poverty line, 50% vulnerability line |

| Age | Householder between the ages of 18 and 65 |

| Gender | Householder gender; male: 1, female: 0 |

| Education (years) | Householder education status; illiteracy: 0, primary school: 6, junior high school: 12, college/higher vocational school undergraduate college: 16, master’s degree: 19, doctoral degree: 22 |

| Risk preference | Householder risk preference: 1, other: 0 |

| Risk aversion | Householder risk aversion: 1, other: 0 |

| Farmer | Householder is a farmer: 1, other: 0 |

| Family size | Number of family members |

| Family size squared | The square of the number of family members |

| Debt | Household debt plus 1, then take the natural logarithm |

| Transfer expenditure | Household’s transfer expenditure plus 1, then take the natural logarithm |

| Unhealthy 1 | Number of people in the household who rated themselves as unhealthy |

| Household nonfinancial assets | Household holdings of nonfinancial assets plus 1, then the natural logarithm |

| Housing ownership | Family owns its own home: 1, other: 0 |

| Rural | Household is in a rural area: 1, other: 0 |

| Variable | Observation | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobile payment | 13,798 | 0.378 | 0.485 | 0 | 1 |

| VEP1 | 13,798 | 0.028 | 0.166 | 0 | 1 |

| VEP2 | 13,798 | 0.012 | 0.107 | 0 | 1 |

| Age | 13,798 | 48.42 | 10.20 | 18 | 65 |

| Gender | 13,798 | 0.839 | 0.368 | 0 | 1 |

| Education | 13,798 | 9.970 | 3.936 | 0 | 22 |

| Risk preference | 13,798 | 0.117 | 0.321 | 0 | 1 |

| Risk aversion | 13,798 | 0.574 | 0.495 | 0 | 1 |

| Farmer | 13,798 | 0.595 | 0.491 | 0 | 1 |

| Family size | 13,798 | 3.291 | 1.411 | 1 | 14 |

| Family size squared | 13,798 | 12.82 | 11.69 | 1 | 196 |

| Debt | 13,798 | 4.415 | 4.992 | 0 | 15.54 |

| Transfer expenditure | 13,798 | 0.474 | 0.507 | 0 | 4.879 |

| Unhealthy | 13,798 | 0.382 | 0.727 | 0 | 6 |

| Household nonfinancial assets | 13,798 | 12.69 | 1.764 | 5.303 | 16.36 |

| Housing ownership | 13,798 | 0.851 | 0.356 | 0 | 1 |

| Rural | 13,798 | 0.350 | 0.477 | 0 | 1 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VEP1 | VEP2 | |||||||

| Mobile payment | −0.076 *** | −0.048 *** | −0.030 *** | −0.037 *** | −0.037 *** | −0.022 *** | −0.013 *** | −0.013 *** |

| (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.005) | (0.006) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.003) | (0.005) | |

| Gender | 0.025 *** | 0.016 *** | 0.016 *** | 0.008 ** | 0.005 * | 0.006 * | ||

| (0.006) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.004) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |||

| Age | 0.001 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.001 *** | ||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||

| Education | −0.005 *** | −0.003 *** | −0.002 *** | −0.003 *** | −0.002 *** | −0.001 *** | ||

| (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||

| Risk preference | −0.012 *** | −0.002 | −0.001 | −0.003 | 0.005 | 0.006 * | ||

| (0.004) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |||

| Risk aversion | −0.005 | 0.004 ** | 0.003 * | −0.002 | 0.003 ** | 0.003 ** | ||

| (0.003) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |||

| Farmer | 0.047 *** | 0.027 *** | 0.024 *** | 0.027 *** | 0.019 *** | 0.018 *** | ||

| (0.007) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.005) | |||

| Family size | 0.053 *** | 0.054 *** | 0.033 *** | 0.032 *** | ||||

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |||||

| Family size squared | −0.004 *** | −0.004 *** | −0.002 *** | −0.002 *** | ||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||

| Housing ownership | 0.066 *** | 0.061 *** | 0.034 *** | 0.031 *** | ||||

| (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.006) | (0.006) | |||||

| Rural | 0.019 *** | 0.016 *** | 0.006 *** | 0.004 *** | ||||

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |||||

| Debt | −0.000 ** | −0.000 * | −0.001 *** | −0.001 *** | ||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||

| Transfer expenditure | −0.056 *** | −0.053 *** | −0.036 *** | −0.033 *** | ||||

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.006) | (0.006) | |||||

| Unhealthy | −0.000 | −0.001 | −0.000 | −0.000 | ||||

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |||||

| Household nonfinancial assets | −0.025 *** | −0.023 *** | −0.014 *** | −0.013 *** | ||||

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||

| Province fixed effects | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 12,030 | 12,030 | 12,030 | 11,984 | 10,394 | 10,394 | 10,394 | 10,354 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.140 | 0.235 | 0.666 | 0.127 | 0.231 | 0.742 | ||

| F test | 426.33 | 426.33 | ||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VEP1 | VEP2 | |||||||

| Mobile payment | −0.160 *** | −0.028 *** | −0.050 *** | −0.032 *** | −0.074 ** | −0.013 *** | −0.029 *** | −0.020 *** |

| (0.051) | (0.005) | (0.007) | (0.005) | (0.031) | (0.003) | (0.007) | (0.004) | |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Province fixed effects | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 13,796 | 12,030 | 13,798 | 13,798 | 13,796 | 10,394 | 13,798 | 13,798 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.669 | 0.563 | 0.742 | 0.746 | 0.489 | 0.747 | ||

| Kleibergen–Paap rk LM Statistic | 18.889 | 18.889 | ||||||

| Cragg–Donald Wald F statistic | 157.721 | 157.721 | ||||||

| Hausman test | 12.157 *** | 6.600 ** | ||||||

| (p-value) | (0.002) | (0.016) | ||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurship | VEP1 | VEP2 | Entrepreneurship Survival | ||||

| Mobile payment | 0.070 *** | 0.117 *** | 0.044 | 0.059 *** | |||

| (0.023) | (0.026) | (0.031) | (0.016) | ||||

| Entrepreneurship | −0.008 | −0.009 ** | |||||

| (0.006) | (0.004) | ||||||

| Entrepreneurship survival | −0.010 ** | ||||||

| (0.004) | |||||||

| Entrepreneurial exit | −0.003 | ||||||

| (0.006) | |||||||

| Start-up business | −0.002 | ||||||

| (0.005) | |||||||

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Province fixed effects | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 13,750 | 4806 | 8944 | 12,030 | 10,394 | 10,394 | 13,750 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.658 | 0.740 | 0.740 | ||||

| F test | 426.33 | 25.28 | 267.42 | 426.33 | |||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unemployment Insurance | Business Insurance | Cost of Credit | VEP1 | VEP2 | |||||

| Mobile payment | 0.207 *** | 0.146 *** | −0.037 ** | ||||||

| (0.020) | (0.011) | (0.016) | |||||||

| Unemployment insurance | −0.040 *** | −0.029 *** | |||||||

| (0.014) | (0.008) | ||||||||

| Business insurance | −0.027 *** | −0.016 *** | |||||||

| (0.010) | (0.006) | ||||||||

| Cost of credit | 0.008 ** | 0.008 *** | |||||||

| (0.004) | (0.002) | ||||||||

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Province fixed effects | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 13,750 | 13,750 | 13,750 | 12,030 | 12,030 | 12,030 | 10,394 | 10,394 | 10,394 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.424 | 0.423 | 0.422 | 0.445 | 0.452 | 0.455 | |||

| F test | 426.99 | 426.99 | 426.99 | ||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VEP1 | VEP2 | |||||||

| Mobile payment | −0.083 *** | −0.108 *** | −0.036 *** | −0.032 *** | −0.032 *** | −0.029 *** | −0.024 *** | −0.004 |

| (0.023) | (0.010) | (0.004) | (0.008) | (0.011) | (0.007) | (0.003) | (0.005) | |

| West | −0.064 *** | −0.035 *** | ||||||

| (0.004) | (0.003) | |||||||

| Mobile payment × west | −0.022 ** | −0.056 *** | ||||||

| (0.009) | (0.005) | |||||||

| Central | −0.017 *** | −0.006 *** | ||||||

| (0.003) | (0.002) | |||||||

| Mobile payment × central | 0.014 | 0.003 | ||||||

| (0.009) | (0.005) | |||||||

| Housing ownership | 0.066 *** | 0.034 *** | ||||||

| (0.008) | (0.006) | |||||||

| Rural | 0.019 *** | 0.006 *** | ||||||

| (0.003) | (0.002) | |||||||

| Mobile payment × household income | 0.006 ** | 0.002 ** | ||||||

| (0.003) | (0.001) | |||||||

| Household income | −0.000 | −0.000 | ||||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||||

| Mobile payment × housing ownership | 0.078 *** | 0.016 * | ||||||

| (0.009) | (0.009) | |||||||

| Mobile payment × rural | 0.004 | −0.013 * | ||||||

| (0.009) | (0.007) | |||||||

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Province fixed effects | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 12,030 | 12,030 | 12,030 | 12,030 | 10,394 | 10,394 | 10,394 | 10,394 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.667 | 0.666 | 0.666 | 0.666 | 0.744 | 0.742 | 0.744 | 0.743 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Gong, X.; Zhang, J.; Xiang, Z.; Liao, C. The Impact of Mobile Payment on Household Poverty Vulnerability: A Study Based on CHFS2017 in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14001. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114001

Li Y, Gong X, Zhang J, Xiang Z, Liao C. The Impact of Mobile Payment on Household Poverty Vulnerability: A Study Based on CHFS2017 in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(21):14001. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114001

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yuhua, Xiheng Gong, Jingyi Zhang, Ziwei Xiang, and Chengjun Liao. 2022. "The Impact of Mobile Payment on Household Poverty Vulnerability: A Study Based on CHFS2017 in China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 21: 14001. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114001

APA StyleLi, Y., Gong, X., Zhang, J., Xiang, Z., & Liao, C. (2022). The Impact of Mobile Payment on Household Poverty Vulnerability: A Study Based on CHFS2017 in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 14001. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114001