Demands on Health Information and Clinical Practice Guidelines for Patients from the Perspective of Adults with Mental Illness and Family Members: A Qualitative Study with In-Depth Interviews

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

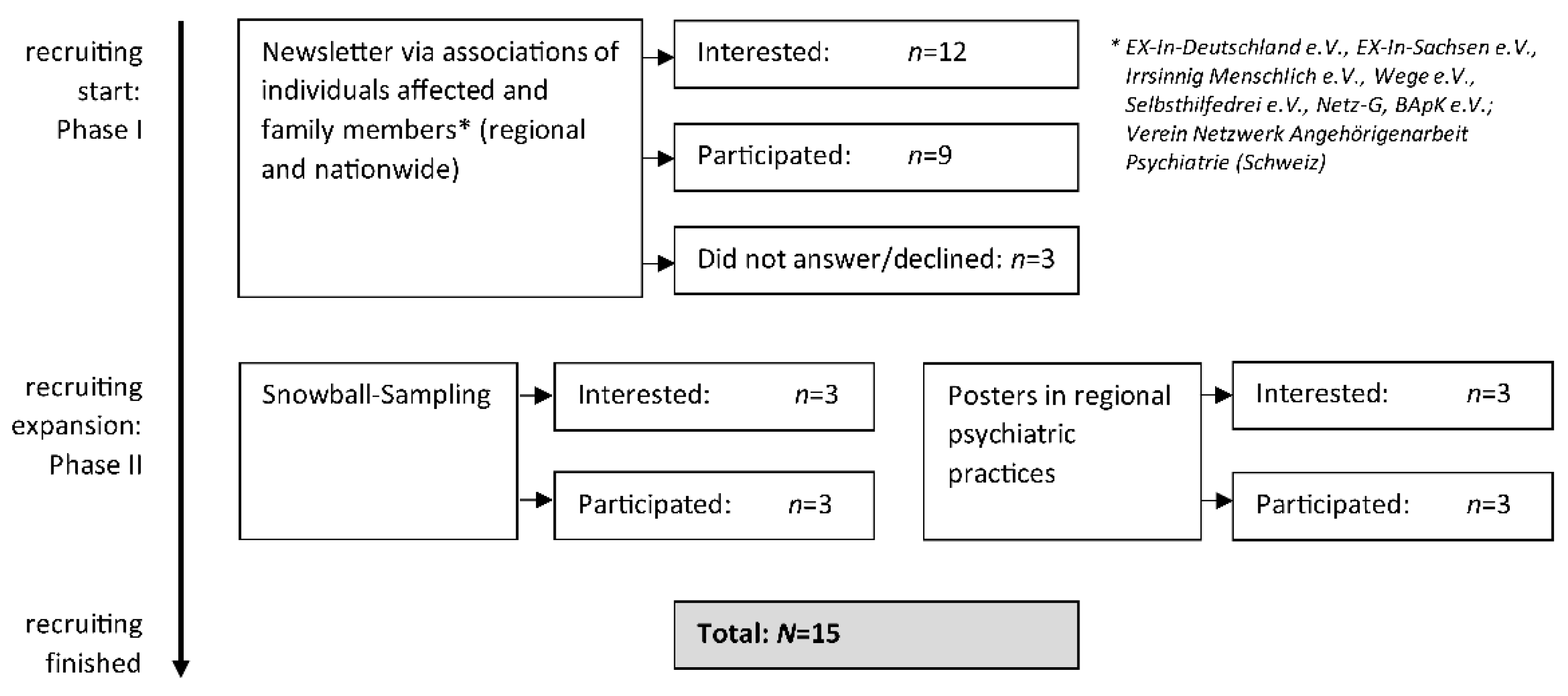

2.2. Participants and Settings

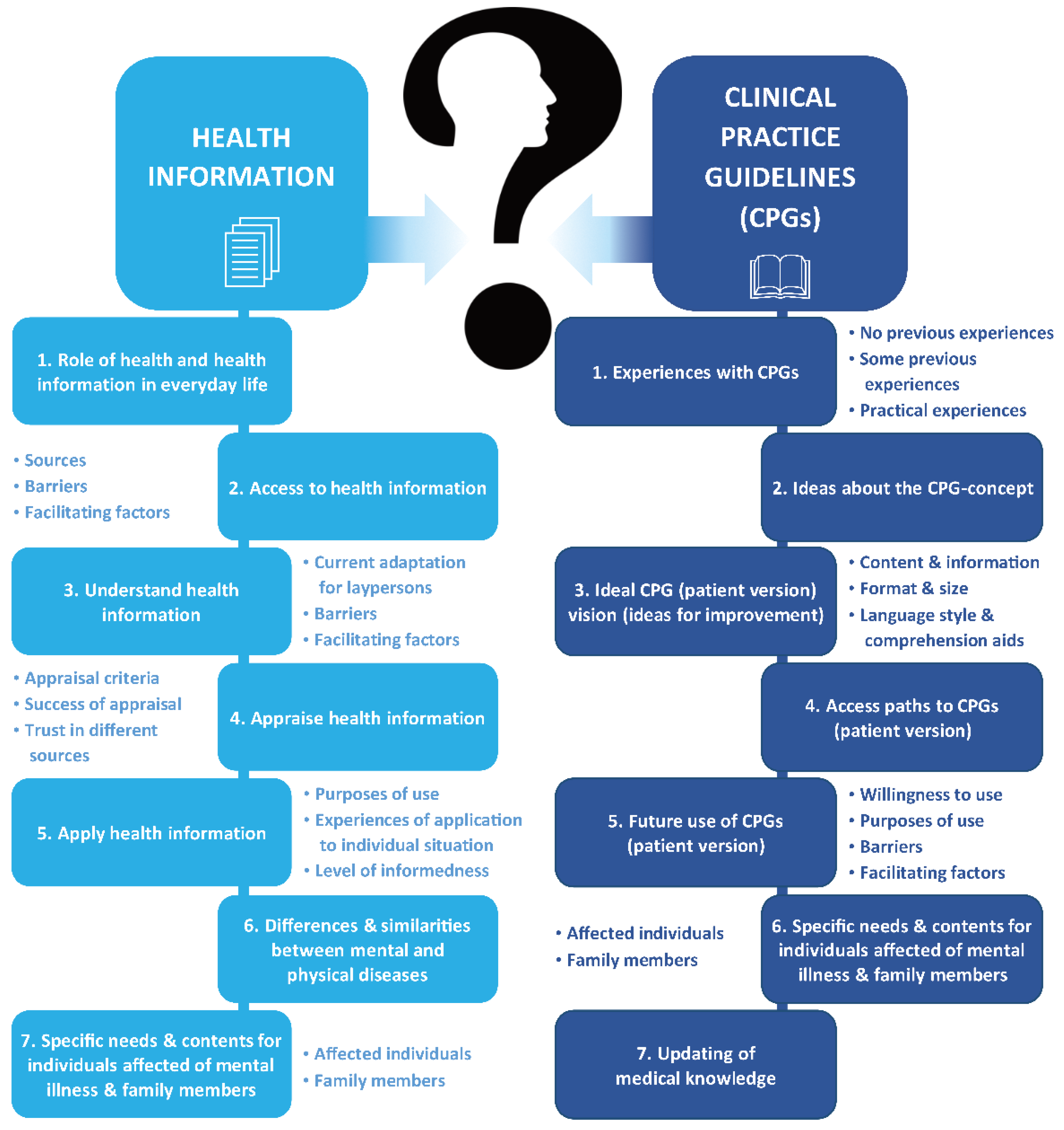

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations and Data Protection

3. Results

3.1. Main Category 1: Health Information

3.1.1. Role of Health and Health Information in Everyday Life

“Yes, a big role, if not the most important, because if you don’t have your health you’re in a bad way. A healthy lifestyle and way of life is the be-all and end-all, so that you can feel well and go about your daily business, your hobbies and so on, and be there for your family […].”(B08)

3.1.2. Access to Health Information

- Daily newspaper

- Associations (e.g., mutual support and self-help, peer counseling) and professional societies

- Health insurance companies (e.g., prevention programs, newsletter)

- Flyer in waiting rooms

- Social environment (e.g., family members, friends, colleagues, persons affected by similar illnesses)

- Documentaries on television, movies, radio programs, podcasts

- Advertisement in public streets and transport

- Academic studies and further education (e.g., medicine, psychology, social work), “health information” days in schools, lay lectures on health topics.

“On the internet […] a quick Google search if I’ve got a niggle and that sort of thing as a source of information. […] I like to pick up health magazines at the pharmacy, sure. But if there are particular issues that affect me, or affect me as a family member particularly now that my mother is ill, then I’ll find literature and books and I’ll look for advice on recommended books at the [author’s note: self-help] association.”(B08)

- Primarily, lack of knowledge about sources for specific information (especially about institutions, associations and consultancy services)

- Information overload (especially when searching online), resulting in difficulties filtering out optimal information for the individual situation from the high number of results

- Difficulties successfully performing a search when very specific information is needed (e.g., on a more specific topic and not on the most common therapy option)

- When a certain prior knowledge was needed as a prerequisite for a successful search (e.g., specialist terms, psychiatric diagnosis)

- Lack of clarity of available support structures as well as bureaucratic barriers (e.g., when applying for financial or socio-medical support)

- Convoluted web portal pages

- Long waiting times for therapy appointments

- Lack of drive (e.g., in acute phases of a mental illness)

- Stigmatization of mental illnesses inhibited seeking help.

“Once you find the right place, you’ll find really good information on certain sites or about certain topics. Well presented, too. I think the real problem is getting there. Or that there’s just too much information out there that’s not necessarily useful.”(B07)

- Offers tailored to specific target group and its needs (e.g., lectures for family members, psychoeducation in day or inpatient clinics or rehabilitation)

- Enabling a targeted internet search via everyday language terms and symptom descriptions

- Provision of information free of charge

- Provision of information in everyday contexts (e.g., daily newspaper or advertisements in public spaces)

- Central platforms or well-known reputable websites as starting points for an internet search

- Receive information automatically without having to act yourself or to ask (e.g., via physicians, socio-medical or psycho-social supporters or health insurance companies)

- Feeling addressed by the presentation of health information (e.g., because of design or appeal).

“When I was first confronted with the illness in 1999 and my son was admitted to hospital, they organized a seminar for family members for the very first time. We were told about the individual illnesses and that happened ten times over the course of an evening, and that was really good.”(B11)

3.1.3. Understand Health Information

“It varies, of course. I’ve seen many texts that I find difficult to understand in the sense that they’ve used medical terms or simply tried to sound fancy, especially when talking about the psyche, so that you always need a certain amount of background knowledge or a certain IQ level, so to speak […].”(B04)

“A bigger problem, as I see it, are statistical estimates and results, for instance. […] Such complex matters just aren’t so easy to explain. And you probably need deeper knowledge of a topic to be able to evaluate study results or to even understand on what basis or how study results are achieved, and what it means to have a result that clearly leads to a certain result in this case.”(B07)

“[…] when affected people read it […] they are mostly going through a phase where they are not doing well at all. They are not being receptive. I’ve experienced it myself. I also noticed in the hospital, in psychoeducation, that the first few times there just went completely past me. I couldn’t absorb it at all because I wasn’t well enough. And it’s exactly the same if you try to read something in that state. Not a lot of it will stick, unfortunately.”(B01)

- Simpler wording, complemented with a version or summary following easy-to-read rules

- Explanation of specialist terms

- Inclusive and stigma-free language style, involving individuals affected by mental illness in the production and revision of health information

- Design elements to promote comprehension (e.g., creating a structure with headings, lists and paragraphs; visualization with graphics, diagrams, pictures and tables)

- Multiple versions: “introductory version” for people with little prior knowledge, “advanced version” for more experienced people

- Inclusion of field reports and case studies

- Additional multi-media elements (e.g., print and digital products, audio and video material).

“[…] then again, the easy-to-read language is too easy for some people […] It’s important for people with psychiatric diagnoses that there is something between the lofty language or jargon, whether bureaucratic or medical, and the easy-to-read language. There has got to be something in between. And there have been attempts at that, I think. But it shouldn’t come across as didactic, I mean it must be self-explanatory. The vocabulary should be easily understandable.”(B03)

3.1.4. Appraise Health Information

“I think it depends on the source. If I trust the source, then I’m more likely to trust the information too. […] I trust things more if they are presented to me as a possibility and an option and maybe as predominantly good experiences or recommendations, but not as the ultimate truth.”(B10)

“The balance between pros and cons, limitations, possibilities, whatever they may be. Diversity, that is, that they’re not just trying to make a specific point but instead you can see that someone’s considered the big picture, not just the topic at hand or whatever might be in their interest.”(B10)

“I do my best, yes. In books, the sources are mostly stated properly. On the internet, let’s just say, I pay close attention to it, and if it’s a well-founded text, then the sources are usually mentioned. I’d like to think that I’m well-informed these days, if I make the effort. You have to take the time for it, though.”(B15)

“Well, on the internet you have to look closely at whatever it is you found, what the sources are. There are millions of articles out there and not all of them are trustworthy. Compared to that, a book that I’ve picked out or got from the library is a safer source, a good source indeed.”(B08)

3.1.5. Apply Health Information

- Raise awareness of illness progression and deterioration of health status

- Acquire psychoeducation (for themselves and for others)

- Optimize prevention behavior

- Search for therapy options

- Develop rules for dealing with ill family members and friends.

“Yes, of course, if you’ve done some reading, you’re able to, I think, it’s helpful in the sense that you can ask specific questions about a treatment or you can say, look, I’ve heard about this here, could this be an option? It’s useful in that respect.”(B15)

“Yes, by now really well. But that too was a long way. Getting started was slow going, you first had to find out who even is there that can help you along. These days I would say that I’m well-informed, but it wasn’t—. It was a long way to get there.”(B15)

“Often it works. But—. Well, sometimes it’s difficult for family members to judge certain things or to estimate their extent. Or to apply the recommended steps in the first place. That is, to look for a therapy or make an appointment with a specialist, for instance. To even access the appropriate places. I mean, it’s nice that that they say I should see a therapist under certain conditions. But if I can’t reach one or I have to make a large advance payment myself, well that’s a hurdle I’m going to have to clear first.”(B07)

“Yes, very often. When I was sick at home, I did a lot of googling on things like inner restlessness and how to let go. Let go of thoughts I mean. Meditation techniques, relaxation techniques. I did a lot of searching, tried out a lot of things and used them for myself, yes.”(B06)

3.1.6. Differences and Similarities between Mental and Physical Diseases

“I believe, just because physical illness is naturally easier to isolate and describe, that it’s much easier to gather information and to say precisely, this is what the patient has and these are our options. You can see in the body what the problem is. ‘Mental illness’ in comparison, is a massive field, and you can always only make assumptions, also as a psychiatrist or a therapist, based on what you’re told or what you’ve observed. You can’t really look inside a person. And I think because of that the information on physical things is a lot more specific and you can say that if you’ve got a broken leg, then you’ve got—. If you’ve got coeliac disease, you’ve got to do this or that. But for those with autism, there isn’t a single way that applies to everyone. That’s what I meant before, it’s always only about the individual patient. And what’s good for you varies from person to person. That’s why I find information on physical problems is much easier to present and access.”(B09)

3.1.7. Specific Needs and Content for Individuals Affected by Mental Illness and Family Members Regarding Health Information

“I only know that when I was acutely depressed, and I was fairly deeply depressed, I wasn’t able to do or look for anything. I actually could have used someone to take me by the hand or give me a relatively simple text that says: ‘This is what it’s like, these are the typical symptoms. It’s normal, so no need to worry. And these are the treatment options’.”(B01)

“I have depression, and there are other people who have depression for completely different reasons. What helps can also vary. Some people find medication helpful, others not so much. Others find talking more useful, or just some activities or something. That’s why I think a broad perspective is always important.”(B02)

3.2. Main Category 2: Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs)

3.2.1. Experiences with CPGs

“No, it may be that I’ve come across it accidentally while searching online, without realizing that it’s a medical guideline, even if I can’t recall it now. But, that someone would have proactively handed one to me, I wouldn’t be aware of it at least.”(B09)

“I don’t think you can make it shorter. Sure, it was long, but it has to be like this, you can’t condense it any further. It was to the point, without long, convoluted sentences that didn’t pertain to the subject or distracted from the subject. No, it was very good. You could certainly make it a lot longer, but it’s not going to make it more helpful.”(B08)

3.2.2. Ideas about the CPG-Concept

“How would I describe a medical guideline? It’s definitely a mixed bag, a diverse and very large collection of information, where you will definitely find what you’re looking for. And this information will also contain further links or tips and literature references. A mixed bag is an appropriate term, or you could also say ‘compendium’.”(B08)

3.2.3. Ideal CPG (Patient Version) Vision (Ideas for Improvement)

- Commonalities of mental illnesses

- Biopsychosocial model

- Etiology of the specific illness

- Clinical symptomatology

- Prevention and treatment options (medication, psychotherapy, psychosocial therapies)

- Mutual support and self-help groups, associations and counseling centers (including local addresses) as a leaflet or online

- Financial support services, socio-medical offers, and legal rights.

“Firstly, an explanation of the illness itself because, if it’s your first time going through something like it, you have no idea what’s happening to you and you’re doubting yourself. […] it would be great if you could easily find something online […] where it says: ‘OK, these are the symptoms of depression’. Just so you’d know that you don’t have to worry so much and be totally afraid, that it’s normal and also treatable. There is hope, you just have to admit yourself to treatment. Of course, you also have to be open to treatment. […] And then, a relatively simple breakdown of therapy options, what they are good for, what effect they are supposed to have. And the piece of information that options like rehabilitation exist […]”(B01)

“To give the affected person or the family, or let’s just say, to give the affected person the feeling that there’s something they can do. And it goes on […] when you notice, I’m doing this well now and I’ve made it back home. What more can I do? And then to give you ideas, oh, here’s another good thing I can do for myself, another way I can support myself in getting better.”(B12)

“That you could get at least halfway back to being well or that you could live a good life as a mentally ill person.”(B11)

“I could imagine a brochure with maybe 15 different descriptions of illnesses. Two to two and a half, two or three pages at most would be good. I think that would be enough to get a good overview.”(B12)

- Different versions: (1) standard version with scientific yet comprehensible language, (2) version in easy-to-read language and (3) a version for children

- Avoidance of specialist terms or explanations when necessary for understanding (glossary should be included)

- Optimistic and encouraging as well as inclusive, non-stigmatizing and gender-neutral wording

- Involvement of target group representatives (e.g., by having individuals affected by mental illness check and improve the wording).

“[…] that you talk about it like you would about any other normal thing and not in a judging tone. […] That the language is kept understandable, as I said, you could perhaps explain medical concepts in simple terms in an aside. That it’s multifaceted […], you could maybe also say, okay, for those who prefer, here’s a link that you can enter on the internet to see an informative video, for instance. For people who are more interested in visual material.”(B04)

- A summary that provided an overview, followed by more in-depth information

- Text structured in blocks, combined with key points and subheadings

- Case studies and field reports

- Visual elements (e.g., diagrams, pictures, speech boxes, graphical depiction of treatment paths)

- Multimedia elements (e.g., supplementary explanatory videos of 3–10 min).

“What I think actually makes sense, or what I always really like and sometimes kind of lightens it up is when there are sections here and there with first-person accounts. […] It lightens the whole thing up because it’s something practical.”(B02)

3.2.4. Access Paths to CPGs (Patient Version)

“They could be available in all sorts of places, flyers maybe or information leaflets. In public libraries or wherever people like to frequent. In opera houses too, for all I care, places of culture like that. Or in bookshops. I wonder who I’m missing though... Where else should they be available? There are cafes with lots of flyers. They could be included. Cinemas as well. Perhaps even places where you wouldn’t necessarily–. Where you wouldn’t expect to be confronted with the topic [author’s note: of mental illnesses]. […] I mean places where you’ll find a great many people and also people of various backgrounds and ages. In order to achieve a really massive reach. Especially in the case of mental illnesses, I don’t think you can–. They need to be in so many places, because I think the number of people affected is incredibly large.”(B12)

3.2.5. Future Use of CPGs (Patient Version)

- enhancing consultation with their doctor about therapy options

- education about alternatives to standard treatment options

- information about self-care (e.g., nutrition, exercise, additional psychosocial therapy)

- addresses of additional support options such as psychosocial counseling

- materials for family members and friends for psychoeducation to reduce stigma associated with mental illness.

“Definitely, because, well, you’ll be informed when you turn up for your consultation. And if you’ve got questions to ask, otherwise you wouldn’t even come up with questions like whether this therapy option would be a possibility. You just wouldn’t know about it. The doctor can’t just recite entire guidelines in a consultation.”(B08)

“Yes, definitely. As I said, all that is not so important to me anymore, now that I know it. I’ve had it for a couple of years now. But in the past it would have been very, very important to me.”(B01)

“There’s nothing that would hinder me directly, other than that such a long text is naturally cumbersome to deal with and it takes a while to get into it.”(B07)

“I think it’s good if it’s easily accessible on the internet. That makes it easier, of course. I personally would buy also a book, no doubt about it, but if it’s available free of charge, whether digitally or as a brochure or a book, that makes it easier, of course.”(B15)

3.2.6. Specific Needs and Content for Individuals Affected of Mental Illness and Family Members Regarding CPGs (Patient Version)

“I see two clearly different situations: I’m someone at the very beginning and notice that things just aren’t working right now. Everyone wants something from me and I can’t handle it somehow. I feel overwhelmed and I’m having emotional outbursts just like that without knowing why. What is needed at that moment is basic, concise information and first-aid guidance, so that you can feel understood and you’ll have a word for it, or that you’ll know where to turn and you don’t have to just take it or wait any longer. And then there are information leaflets that are meant for people whose situation is more advanced, who perhaps are looking for a therapist or who are somehow deeper in it.”(B04)

- Advice for social interaction with the person affected by mental illness (“dos and don’ts”)

- Information on what you can do together at home in everyday life to reduce symptoms and to favorably influence the course of the illness

- Tips for self-care

- Advice for dealing with feelings of powerlessness and despair

- Encouragement to seek help for oneself when needed.

“I mean, we’ve reached a dead end with my mother. It would be nice if there were a chapter called ‘How to get out of a dead end’, but I’m being realistic. They are put together in such a way that–. There are many therapies that are being offered, and if the patient is willing to go along with all that, that’s great, but—. Oh, it’s difficult. Anyway, I can’t remember at all if there was a chapter specifically for family members saying ‘do not bury your head in the sand, seek help for yourself before you get burned out on the illnesses of a family member’. That’s also important.”(B08)

3.2.7. Updating of Medical Knowledge

“That may be something that concerns me personally. When you see that things are moving forward. You can somehow compare to situation now to seven years ago. Back then, people used to think this and now the view is different. I find it positive to notice that research is progressing and that at some point, when you’re older, you might be able to compare things.”(B04)

“Very confusing. The thing is, you might read an article today about a study in which it was found that the causes of such and such illness are such and such. Four days later another study comes out that does the exact same thing but with completely opposite results. I think that is the problem and at some point it just gets too much. The sheer volume of it.”(B02)

4. Discussion

4.1. Sources of Health Information and CPGs

4.2. Target-Group Specific Adaption

4.3. Trust-Increasing Features

4.4. Mental Health Literacy and Empowerment

4.5. Specifics of Online Sources of Health Information and CPGs

4.6. Specifics of Mental Illnesses and the Role of Stigma

4.7. Strength and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Steel, Z.; Marnane, C.; Iranpour, C.; Chey, T.; Jackson, J.W.; Patel, V.; Silove, D. The global prevalence of common mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis 1980–2013. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 43, 476–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rehm, J.; Shield, K.D. Global burden of disease and the impact of mental and addictive disorders. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moitra, M.; Santomauro, D.; Collins, P.Y.; Vos, T.; Whiteford, H.; Saxena, S.; Ferrari, A.J. The global gap in treatment coverage for major depressive disorder in 84 countries from 2000–2019: A systematic review and Bayesian meta-regression analysis. PLoS Med. 2022, 19, e1003901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.S.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Alonso, J.; Angermeyer, M.C.; Borges, G.; Bromet, E.J.; Bruffaerts, R.; de Girolamo, G.; de Graaf, R.; Gureje, O.; et al. Use of mental health services for anxiety, mood, and substance disorders in 17 countries in the WHO world mental health surveys. Lancet 2007, 370, 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, P.S.; Angermeyer, M.C.; Borges, G.; Bruffaerts, R.; Tat Chiu, W.; de Girolamo, G.; Fayyad, J.; Gureje, O.; Haro, J.M.; Huang, Y.; et al. Delay and failure in treatment seeking after first onset of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry 2007, 6, 177–185. [Google Scholar]

- Borges, G.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Andrade, L.; Benjet, C.; Cia, A.; Kessler, R.C.; Orozco, R.; Sampson, N.; Stagnaro, J.C.; Torres, Y.; et al. Twelve-month mental health service use in six countries of the Americas: A regional report from the World Mental Health Surveys. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2019, 29, e53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Latzman, N.E.; Ringeisen, H.; Forman-Hoffman, V.L.; Munoz, B.; Miller, S.; Hedden, S.L. Trends in mental health service use by age among adults with serious mental illness. Ann. Epidemiol. 2019, 30, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Girolamo, G.; Dagani, J.; Purcell, R.; Cocchi, A.; McGorry, P.D. Age of onset of mental disorders and use of mental health services: Needs, opportunities and obstacles. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2012, 21, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fikretoglu, D.; Liu, A. Perceived barriers to mental health treatment among individuals with a past-year disorder onset: Findings from a Canadian Population Health Survey. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2015, 50, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, M.K.; Crome, E.; Sunderland, M.; Wuthrich, V.M. Perceived needs for mental health care and barriers to treatment across age groups. Aging Ment. Health 2017, 21, 1072–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, K.; van den Broucke, S.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Pelikan, J.; Slonska, Z.; Brand, H. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HLS-EU Consortium. Comparative Report of Health Literacy in Eight EU Member States. The European Health Literacy Survey HLS-EU (Second Revised and Extended Version). 2014. Available online: https://cdn1.sph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/135/2015/09/neu_rev_hls-eu_report_2015_05_13_lit.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Schaeffer, D.; Berens, E.-M.; Vogt, D.; Gille, S.; Griese, L.; Klinger, J.; Hurrelmann, K. Health literacy in Germany: Findings of a representative follow-up survey. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2021, 118, 723–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degan, T.J.; Kelly, P.J.; Robinson, L.D.; Deane, F.P.; Smith, A.M. Health literacy of people living with mental illness or substance use disorders: A systematic review. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2021, 15, 1454–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutcher, S.; Wei, Y.; Coniglio, C. Mental health literacy: Past, present, and future. Can. J. Psychiatry 2016, 61, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jorm, A.F.; Korten, A.E.; Jacomb, P.A.; Christensen, H.; Rodgers, B.; Pollitt, P. “Mental health literacy”: A survey of the public’s ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Med. J. Aust. 1997, 166, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonabi, H.; Müller, M.; Ajdacic-Gross, V.; Eisele, J.; Rodgers, S.; Seifritz, E.; Rössler, W.; Rüsch, N. Mental health literacy, attitudes to help seeking, and perceived need as predictors of mental health service use: A longitudinal study. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2016, 204, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Waldmann, T.; Staiger, T.; Oexle, N.; Rüsch, N. Mental health literacy and help-seeking among unemployed people with mental health problems. J. Ment. Health 2020, 29, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, H.S.; Fernandez, P.A.; Lim, H.K. Family engagement as part of managing patients with mental illness in primary care. Singap. Med. J. 2021, 62, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, F.; Holzhüter, F.; Heres, S.; Hamann, J. ‘Triadic’ shared decision making in mental health: Experiences and expectations of service users, caregivers and clinicians in Germany. Health Expect. 2021, 24, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Plummer, V.; Lam, L.; Cross, W. Perceptions of shared decision-making in severe mental illness: An integrative review. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 27, 103–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbeitsgruppe GPGI. Gute Praxis Gesundheitsinformation. Z. Evid. Fortbild. Qual. Gesundhwes. 2016, 110–111, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, A.; Ellins, J. Effectiveness of strategies for informing, educating, and involving patients. BMJ 2007, 335, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stacey, D.; Légaré, F.; Lewis, K.; Barry, M.J.; Bennett, C.L.; Eden, K.B.; Holmes-Rovner, M.; Llewellyn-Thomas, H.; Lyddiatt, A.; Thomson, R.; et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 4, CD001431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Spatz, E.S.; Krumholz, H.M.; Moulton, B.W. The new era of informed consent: Getting to a reasonable-patient standard through shared decision making. JAMA 2016, 315, 2063–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gesetz zur Verbesserung der Rechte von Patientinnen und Patienten. Bundesgesetzblatt 2013, 9, 277–282. Available online: http://www.bgbl.de/xaver/bgbl/start.xav?startbk=Bundesanzeiger_BGBl&jumpTo=bgbl113s0277.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2022).

- Karačić, J.; Dondio, P.; Buljan, I.; Hren, D.; Marušić, A. Languages for different health information readers: Multitrait-multimethod content analysis of Cochrane systematic reviews textual summary formats. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lühnen, J.; Albrecht, M.; Mühlhauser, I.; Steckelberg, A. Leitlinie Evidenzbasierte Gesundheitsinformation. Available online: http://www.leitlinie-gesundheitsinformation.de/ (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Murad, M.H. Clinical practice guidelines: A primer on development and dissemination. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017, 92, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Institute of Medicine. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust; Institute of Medicine: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; ISBN 9780309164221. [Google Scholar]

- Loudon, K.; Santesso, N.; Callaghan, M.; Thornton, J.; Harbour, J.; Graham, K.; Harbour, R.; Kunnamo, I.; Liira, H.; McFarlane, E.; et al. Patient and public attitudes to and awareness of clinical practice guidelines: A systematic review with thematic and narrative syntheses. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Légaré, F.; Boivin, A.; van der Weijden, T.; Pakenham, C.; Burgers, J.; Légaré, J.; St-Jacques, S.; Gagnon, S. Patient and public involvement in clinical practice guidelines: A knowledge synthesis of existing programs. Med. Decis. Mak. 2011, 31, E45–E74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipper, K.; Bakker, M.; de Wit, M.; Ket, J.C.F.; Abma, T.A. Strategies for disseminating recommendations or guidelines to patients: A systematic review. Implement. Sci. 2016, 11, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Correa, V.C.; Lugo-Agudelo, L.H.; Aguirre-Acevedo, D.C.; Contreras, J.A.P.; Borrero, A.M.P.; Patiño-Lugo, D.F.; Valencia, D.A.C. Individual, health system, and contextual barriers and facilitators for the implementation of clinical practice guidelines: A systematic metareview. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2020, 18, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, E.M.; Moriana, J.A. Clinical guideline implementation strategies for common mental health disorders. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2016, 9, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagliardi, A.R.; Alhabib, S. Trends in guideline implementation: A scoping systematic review. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witzel, A. Das problemzentrierte Interview. In Qualitative Forschung in der Psychologie: Grundfragen, Verfahrensweisen, Anwendungsfelder; Jüttemann, G., Ed.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 1985; pp. 227–255. ISBN 3-407-54680-7. [Google Scholar]

- Roehr, S.; Wittmann, F.; Jung, F.; Hoffmann, R.; Renner, A.; Dams, J.; Grochtdreis, T.; Kersting, A.; König, H.-H.; Riedel-Heller, S.G. Strategien zur Rekrutierung von Geflüchteten für Interventionsstudien: Erkenntnisse aus dem “Sanadak”-Trial. Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol. 2019, 69, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P.; Fenzl, T. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. In Handbuch Methoden der Empirischen Sozialforschung; Baur, N., Blasius, J., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; pp. 633–648. ISBN 978-3-658-21307-7. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, B.J.; McMillen, J.C.; Proctor, E.K.; Carpenter, C.R.; Griffey, R.T.; Bunger, A.C.; Glass, J.E.; York, J.L. A compilation of strategies for implementing clinical innovations in health and mental health. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2012, 69, 123–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Flodgren, G.; Hall, A.M.; Goulding, L.; Eccles, M.P.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Leng, G.C.; Shepperd, S. Tools developed and disseminated by guideline producers to promote the uptake of their guidelines. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 8, CD010669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pereira, V.C.; Silva, S.N.; Carvalho, V.K.S.; Zanghelini, F.; Barreto, J.O.M. Strategies for the implementation of clinical practice guidelines in public health: An overview of systematic reviews. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2022, 20, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, B.J.; Proctor, E.K.; Glass, J.E. A systematic review of strategies for implementing empirically supported mental health interventions. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2014, 24, 192–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gühne, U.; Quittschalle, J.; Kösters, M.; Riedel-Heller, S.G. Psychosoziale Therapien für Eine Verbesserte Partizipation am Gesellschaftlichen Leben: Schulungsmaterial zur Informationsveranstaltung für Menschen mit (Schweren) Psychischen Erkrankungen, 1st ed.; Psychiatrie Verlag: Köln, Germany, 2021; ISBN 9783966051231. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Hay, J.L.; Waters, E.A.; Kiviniemi, M.T.; Biddle, C.; Schofield, E.; Li, Y.; Kaphingst, K.; Orom, H. Health literacy and use and trust in health information. J. Health Commun. 2018, 23, 724–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert Koch-Institut. Informationsbedarf der Bevölkerung Deutschlands zu gesundheitsrelevanten Themen—Ergebnisse der KomPaS-Studie. J. Health Monit. 2021, 2021, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolphi, J.M.; Berg, R.; Marlenga, B. Who and how: Exploring the preferred senders and channels of mental health information for Wisconsin farmers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, E.; Czerwinski, F.; Rosset, M.; Großmann, U. Wie Informieren sich die Deutschen zu Gesundheitsthemen? Überblick und Erste Ergebnisse der HINTS Germany-Studie zum Gesundheitsinformationsverhalten der Deutschen. Available online: https://www.stiftung-gesundheitswissen.de/sites/default/files/pdf/trendmonitor_Ausgabe%201.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2022).

- Aoki, Y. Shared decision making for adults with severe mental illness: A concept analysis. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 2020, 17, e12365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Academy of Medical Sciences. Enhancing the Use of Scientific Evidence to Judge the Potential Benefits and Harms of Medicines. Available online: https://acmedsci.ac.uk/file-download/44970096 (accessed on 2 May 2022).

- Zipkin, D.A.; Umscheid, C.A.; Keating, N.L.; Allen, E.; Aung, K.; Beyth, R.; Kaatz, S.; Mann, D.M.; Sussman, J.B.; Korenstein, D.; et al. Evidence-based risk communication: A systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2014, 161, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gühne, U.; Fricke, R.; Schliebener, G.; Becker, T.; Riedel-Heller, S.G. Psychosoziale Therapien bei Schweren Psychischen Erkrankungen; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; ISBN 978-3-662-58739-3. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesärztekammer (BÄK); Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV); Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF); Deutschen Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik und Nervenheilkunde (DGPPN). Patientenleitlinie zur S3-Leitlinie/Nationalen VersorgungsLeitlinie “Unipolare Depression”, 2nd ed. 2016. Version 2. Available online: https://www.patienten-information.de/medien/patientenleitlinien/depression-2aufl-vers2-pll.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2022). [CrossRef]

- SIGN. Autism: A Booklet for Adults, Friends, Family Members and Carers; Healthcare Improvement Scotland: Edinburgh, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-1-909103-45-0. [Google Scholar]

- SIGN. Eating Disorders: A Booklet for People Living with Eating Disorders; Healthcare Improvement Scotland: Edinburgh, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, E.M.; Moriana, J.A. User involvement in the implementation of clinical guidelines for common mental health disorders: A review and compilation of strategies and resources. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2016, 14, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oxman, A.D.; Glenton, C.; Flottorp, S.; Lewin, S.; Rosenbaum, S.; Fretheim, A. Development of a checklist for people communicating evidence-based information about the effects of healthcare interventions: A mixed methods study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e036348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posch, N.; Horvath, K.; Wratschko, K.; Plath, J.; Brodnig, R.; Siebenhofer, A. Written patient information materials used in general practices fail to meet acceptable quality standards. BMC Fam. Pract. 2020, 21, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gühne, U.; Weinmann, S.; Riedel-Heller, S.G. S3-Leitlinie Psychosoziale Therapien bei schweren psychischen Erkrankungen: S3-Praxisleitlinien in Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; ISBN 978-3-662-58284-8. [Google Scholar]

- Böhm, M.; Stiglbauer, B. Verbesserung der Lebensqualität durch psychosoziale Nachsorge? Psychiatr. Prax. 2021, 48, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burr, C.; Rother, K.; Elhilali, L.; Winter, A.; Kozel, B.; Weidling, K.; Zuaboni, G. Rollen und Arbeitsinhalte von Peers und Expertinnen und Experten durch Erfahrung in Praxis, Bildung, Entwicklung und Forschung in der Psychiatrie. Psychiatr. Prax. 2021, 48, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Xie, B. Health literacy in the eHealth era: A systematic review of the literature. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brijnath, B.; Protheroe, J.; Mahtani, K.R.; Antoniades, J. Do web-based mental health literacy interventions improve the mental health literacy of adult consumers? Results from a systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gühne, U.; Quittschalle, J.; Riedel-Heller, S. Thera-Part.de: Die Patientenleitlinie Psychosoziale Therapien bei schweren psychischen Erkrankungen geht online. Psychiatr. Prax. 2019, 46, 412–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbaffi, L.; Rowley, J. Trust and credibility in web-based health information: A review and agenda for future research. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y. Trust in health information websites: A systematic literature review on the antecedents of trust. Health Inform. J. 2016, 22, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sillence, E.; Blythe, J.M.; Briggs, P.; Moss, M. A revised model of trust in internet-based health information and advice: Cross-sectional questionnaire study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e11125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhnen, M.; Dreier, M.; Freuck, J.; Härter, M.; Dirmaier, J. Akzeptanz und Nutzung einer Website mit Gesundheitsinformationen zu psychischen Erkrankungen—www.psychenet.de. Psychiatr. Prax. 2022, 49, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitila, M.; Nummelin, J.; Kortteisto, T.; Pitkänen, A. Service users’ views regarding user involvement in mental health services: A qualitative study. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2018, 32, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doody, O.; Butler, M.P.; Lyons, R.; Newman, D. Families’ experiences of involvement in care planning in mental health services: An integrative literature review. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2017, 24, 412–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schomerus, G.; Stolzenburg, S.; Freitag, S.; Speerforck, S.; Janowitz, D.; Evans-Lacko, S.; Muehlan, H.; Schmidt, S. Stigma as a barrier to recognizing personal mental illness and seeking help: A prospective study among untreated persons with mental illness. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2019, 269, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, A.; Kostaki, E.; Kyriakopoulos, M. The stigma of mental illness in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 243, 469–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aguirre Velasco, A.; Cruz, I.S.S.; Billings, J.; Jimenez, M.; Rowe, S. What are the barriers, facilitators and interventions targeting help-seeking behaviours for common mental health problems in adolescents? A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slade, M.; Longden, E. Empirical evidence about recovery and mental health. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Avdibegović, E.; Hasanović, M. The stigma of mental illness and recovery. Psychiatr. Danub. 2017, 29, 900–905. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kelly, C.M.; Jorm, A.F.; Wright, A. Improving mental health literacy as a strategy to facilitate early intervention for mental disorders. Med. J. Aust. 2007, 187, S26–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patafio, B.; Miller, P.; Baldwin, R.; Taylor, N.; Hyder, S. A systematic mapping review of interventions to improve adolescent mental health literacy, attitudes and behaviours. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2021, 15, 1470–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freţian, A.M.; Graf, P.; Kirchhoff, S.; Glinphratum, G.; Bollweg, T.M.; Sauzet, O.; Bauer, U. The long-term effectiveness of interventions addressing mental health literacy and stigma of mental illness in children and adolescents: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Public Health 2021, 66, 1604072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, B.; Hansson, L. How mental health literacy and experience of mental illness relate to stigmatizing attitudes and social distance towards people with depression or psychosis: A cross-sectional study. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2016, 70, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.E.; Edwards, R. How Many Qualitative Interviews is Enough: Expert Voices and Early Career Reflections on Sampling and Cases in Qualita-tive Research. Available online: https://cris.brighton.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/301922/how_many_interviews.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How many interviews are enough? Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handbuch Methoden der Empirischen Sozialforschung; Baur, N.; Blasius, J. (Eds.) Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; ISBN 978-3-658-21307-7. [Google Scholar]

- von Peter, S.; Bär, G.; Behrisch, B.; Bethmann, A.; Hartung, S.; Kasberg, A.; Wulff, I.; Wright, M. Partizipative Gesundheitsforschung in Deutschland—Quo vadis? Gesundheitswesen 2020, 82, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeker, T.; Glück, R.K.; Ziegenhagen, J.; Göppert, L.; Jänchen, P.; Krispin, H.; Schwarz, J.; von Peter, S. Designed to clash? Reflecting on the practical, personal, and structural challenges of collaborative research in psychiatry. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 701312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total | Affected by Mental Illness | Relative of an Individual Affected by Mental Illness | Both Affected and Relative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 12 | 3 | 5 | 4 |

| Male | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Age in years: minimum–maximum | 30–74 | 30–56 | 36–74 | 33–67 |

| Highest school degree, n | ||||

| Secondary school diploma | 4 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| High school diploma/ baccalaureate/A-level | 11 | 2 | 5 | 4 |

| Highest professional education, n1 | ||||

| Vocational training | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Professional school degree | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| University degree | 6 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Employment situation 2, n | ||||

| Full-time employed (≥35 h) | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Part-time employed (15–34 h) | 7 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| Marginally employed (≤14 h) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Parental leave | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Retired | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Else 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Mental illness, n | ||||

| Unipolar depression | 10 | 4 | 0 | 6 |

| Bipolar depression | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Anxiety disorder | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Personality disorder | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Schizophrenia | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Else 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Duration of illness in years: minimum–maximum | 2–27 | 2.5–20 | 3–22 | 2–27 4 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schladitz, K.; Weitzel, E.C.; Löbner, M.; Soltmann, B.; Jessen, F.; Schmitt, J.; Pfennig, A.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; Gühne, U. Demands on Health Information and Clinical Practice Guidelines for Patients from the Perspective of Adults with Mental Illness and Family Members: A Qualitative Study with In-Depth Interviews. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14262. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114262

Schladitz K, Weitzel EC, Löbner M, Soltmann B, Jessen F, Schmitt J, Pfennig A, Riedel-Heller SG, Gühne U. Demands on Health Information and Clinical Practice Guidelines for Patients from the Perspective of Adults with Mental Illness and Family Members: A Qualitative Study with In-Depth Interviews. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(21):14262. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114262

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchladitz, Katja, Elena C. Weitzel, Margrit Löbner, Bettina Soltmann, Frank Jessen, Jochen Schmitt, Andrea Pfennig, Steffi G. Riedel-Heller, and Uta Gühne. 2022. "Demands on Health Information and Clinical Practice Guidelines for Patients from the Perspective of Adults with Mental Illness and Family Members: A Qualitative Study with In-Depth Interviews" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 21: 14262. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114262

APA StyleSchladitz, K., Weitzel, E. C., Löbner, M., Soltmann, B., Jessen, F., Schmitt, J., Pfennig, A., Riedel-Heller, S. G., & Gühne, U. (2022). Demands on Health Information and Clinical Practice Guidelines for Patients from the Perspective of Adults with Mental Illness and Family Members: A Qualitative Study with In-Depth Interviews. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 14262. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114262