Behind the Silence of the Professional Classroom in Universities: Formation of Cognition-Practice Separation among University Students—A Grounded Theory Study in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

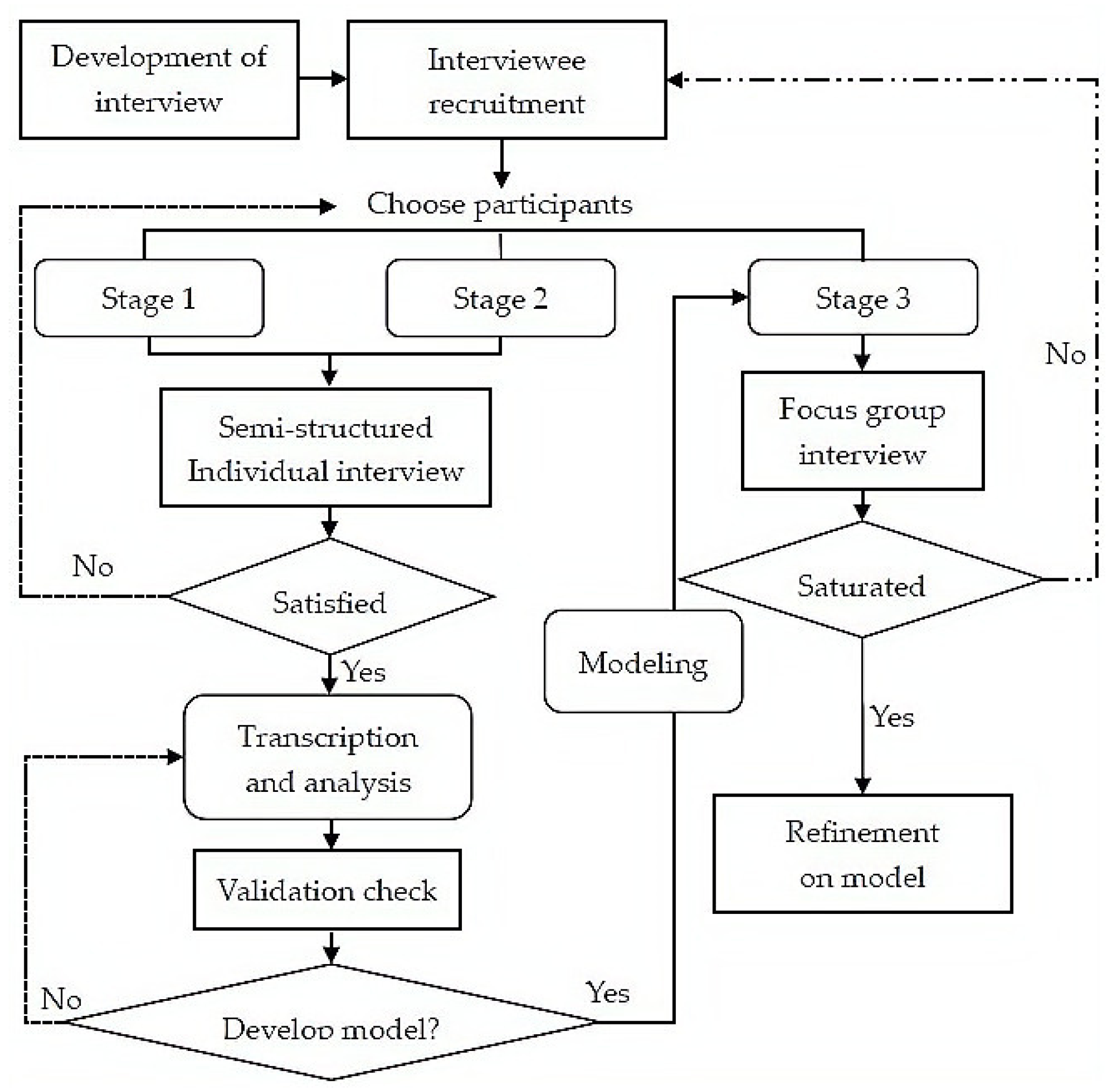

2.2. Procedure

2.2.1. Stage 1

2.2.2. Stage 2

2.2.3. Stage 3

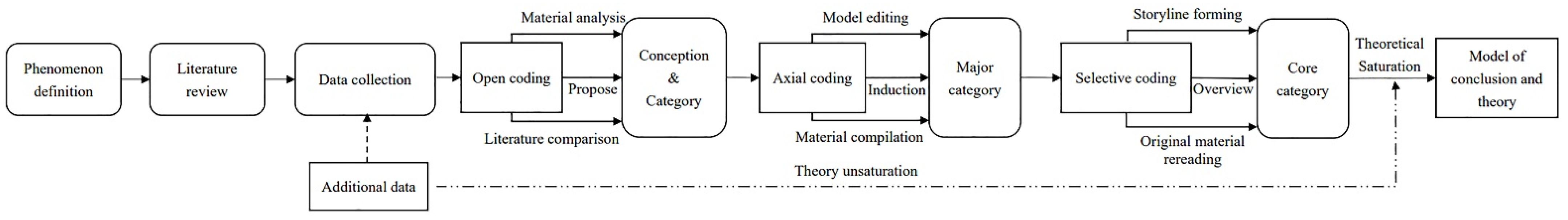

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Theoretical Saturation Test

2.5. Rigor

3. Results and Theory

3.1. Open Coding

3.2. Axial Coding

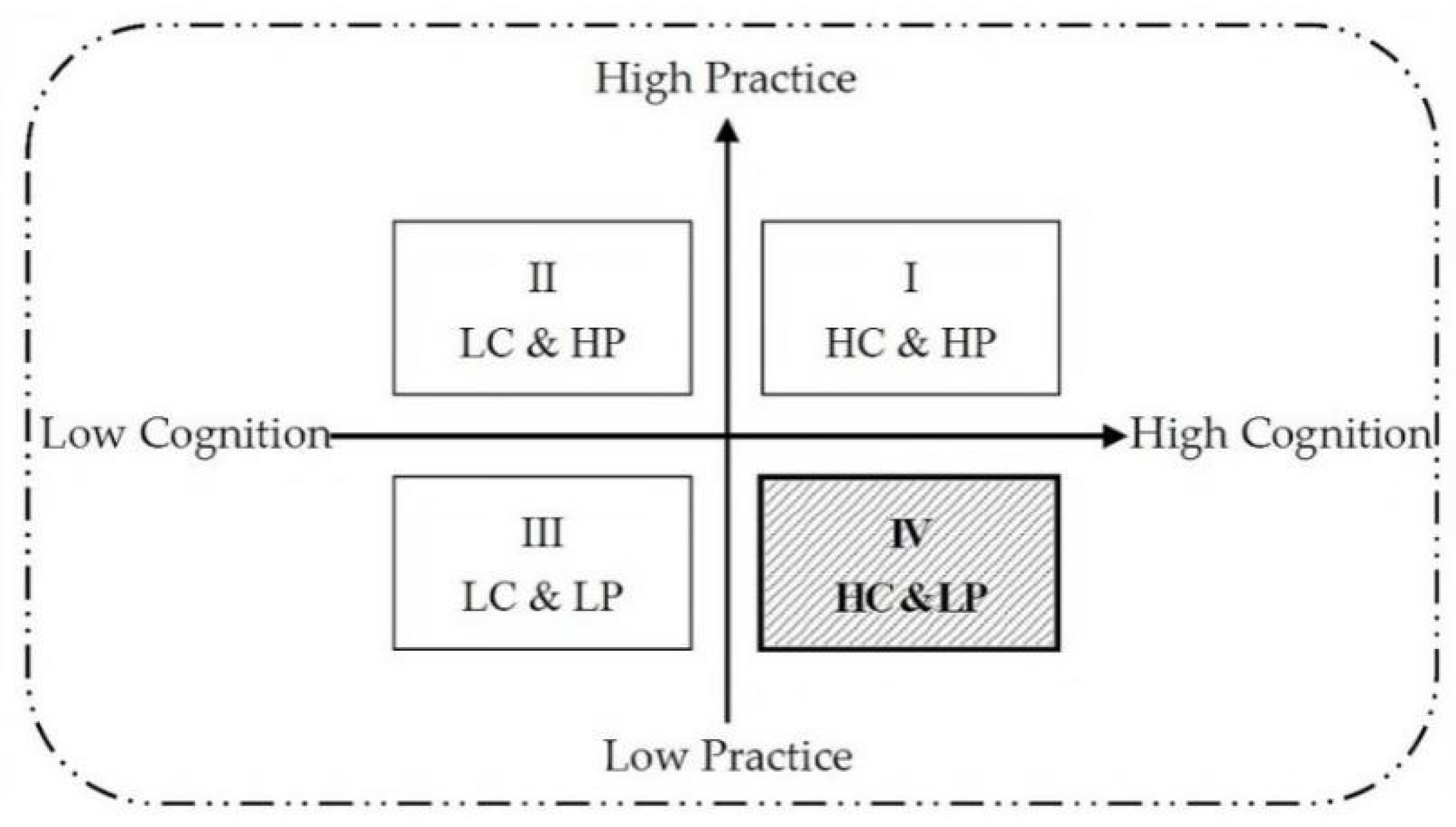

3.3. Selective Coding

3.3.1. Silence Cognition

3.3.2. Silent Behavior

3.3.3. Personality Characteristics

3.3.4. Classroom Experience

3.3.5. Learning Adjustment

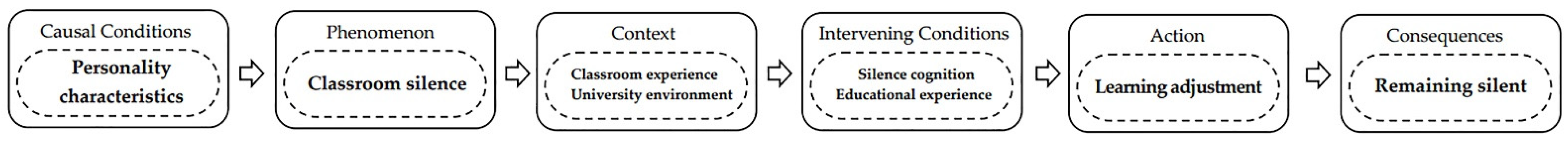

3.4. The Theoretical Model of the Formation and Development of the Phenomenon of Professional Classroom Silence for Chinese Undergraduates Majoring in Education

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary and Discussion

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smith, D.G. College classroom interactions and critical thinking. J. Educ. Psychol. 1977, 69, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeachie, W.J. Research on college teaching: The historical background. J. Educ. Psychol. 1990, 82, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, A.; Han, F.; Ellis, R.A. Combining university student self-regulated learning indicators and engagement with online learning events to predict academic performance. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 2017, 10, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.H. On the relationships between behaviors and achievement in technology-mediated flipped classrooms: A two-phase online behavioral PLS-SEM model. Comput. Educ. 2019, 142, 103653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J. Silence in the second language classrooms of Japanese universities. Appl. Linguist. 2012, 34, 325–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.H. Turning to the Back of Conservative Behavior: Chinese College Students’ Conservative Learning Propensity and Its Influential System—Based on the Empirical Research on the Undergraduate Students Majored Physics in Nanjing University. J. Distance Educ. 2016, 34, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Clepper, G.; Jia, J.; Liu, W. Designing an Interactive Communication Assistance System for Hearing-Impaired College Students Based on Gesture Recognition and Representation. Future Internet 2022, 14, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, M.T.H.; Kang, S.; Yaghmourian, D.L. Why Students Learn More from Dialogue- Than Monologue-Videos: Analyses of Peer Interactions. J. Learn. Sci. 2016, 26, 10–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Cooper, K.; Stephens, M.; Chi, M.; Brownell, S. Learning from error episodes in dialogue-videos: The influence of prior knowledge. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2021, 37, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercellotti, M.L. Do interactive learning spaces increase student achievement? A comparison of classroom context. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 2018, 19, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flowerdew, J.; Miller, L. On the notion of culture in L2 lectures. TESOL Q. 1995, 29, 345–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.F.; Littlewood, W. Why do many students appear reluctant to participate in classroom learning discourse? System 1997, 25, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy-U, M. Motivation for participation or non-participation in group tasks: A dynamic systems model of task-situated willingness to communicate. System 2015, 50, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W.H. Transitioning to a communication-oriented pedagogy: Taiwanese university freshmen's views on class participation. System 2015, 49, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Bresnahan, M. “They make no contribution!” versus “We should make friends with them!”-American domestic students’ perception of Chinese international students’ reticence and face. J. Int. Stud. 2018, 8, 1614–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; McNamara, O. Undergraduate Student Engagement: Theory and Practice in China and the UK; Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.: Singapore, Singapore, 2018; pp. 130–133, 146–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, Y.; Hiver, P. Using a language socialization framework to explore Chinese Students’ L2 Reticence in English language learning. Linguist. Educ. 2021, 61, 100904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, L.; Olliver-Gray, Y. The significance of silence: Differences in meaning, learning styles, and teaching strategies in cross-cultural settings. Psychologia 2006, 49, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, H.; Chen, Y. Engaging Chinese international undergraduate students in the American university. Learn. Teach. 2015, 8, 13–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardelli, D.; Patel, V.K.; Martins-Shannon, J. “Crossing the Rubicon”: Understanding Chinese EFL students’ volitional process underlying in-class participation with the theory of planned behaviour. Educ. Res. Eval. 2017, 23, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, B. The communication patterns of Chinese students with their lecturers in an Australian university. Educ. Stud. 2017, 43, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D. Major Reasons Leading to FLSA. In Foreign Language Learning Anxiety in China; He, D., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, Singapore, 2018; pp. 87–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Hu, W.; McNamara, O. Undergraduate student engagement at a Chinese university: A case study. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 2015, 27, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N. Oral participation in EFL classroom: Perspectives from the administrator, teachers and learners at a Chinese university. System 2015, 53, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Jackson, J. Reticence and Anxiety in Oral English Lessons: A Case Study in China. In Researching Chinese Learners; Jin, L., Cortazzi, M., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2011; pp. 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L. Chinese College Students’Silence in Classroom and Its Evolutive Mechanism—Growing up and adapting of hesitating speaker. China High. Educ. Res. 2018, 12, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wang, Z.; Ma, Q. Teaching Reform of Computer Public Basic Courses in Colleges and Universities in the New Era. Int. J. Inf. Educ. Technol. 2019, 9, 789–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, R.; Liu, P. Educator challenges in the development and delivery of constructivist active and experiential entrepreneurship classrooms in Chinese vocational higher education. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2018, 26, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Kaewsaeng-On, R.; Jin, S.; Anuar, M.M.; Shaikh, J.M.; Mehmood, S. Time lagged investigation of entrepreneurship school innovation climate and students motivational outcomes: Moderating role of students’ attitude toward technology. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 979562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Mok, I.A.C.; Cao, Y. Curriculum reform in China: Student participation in classrooms using a reformed instructional model. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 75, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.X.; Guo, Y.Y. Core competences and scientific literacy: The recent reform of the school science curriculum in China. International J. Sci. Educ. 2018, 40, 1913–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine Transaction: New Brunswick, CA, USA, 1967; pp. 2–3, 1, 61–62, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, H.; Schneider, M. Insights from Alumni: A Grounded Theory Study of a Graduate Program in Sustainability Leadership. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tweed, A.; Charmaz, K. Grounded Theory Methods for Mental Health Practitioners. In Qualitative Research Methods in Mental Health and Psychotherapy: A Guide for Students and Practitioners; Harper, D., Thompson, A.R., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: West Sussex, UK, 2012; pp. 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1998; pp. 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques; SAGE Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1990; p. 197. [Google Scholar]

- Ting, H.; Thurasamy, R. What matters to infrequent customers: A pragmatic approach to understanding perceived value and intention to revisit trendy coffee café. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, C.; Ismail, M.; Ting, H.; Bahri, S.; Sidek, A.; Idris, S.; Tan, R.; Seman, S.; Sethiaram, M.; Ghazali, M.; et al. Consumer behaviour towards pharmaceutical products: A model development. Int. J. Pharm. Healthc. Mark. 2019, 13, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrell, M.C.; Bradley, M.A. Data Collection Methods: Semi-structured Interviews and Focus Groups; RAND: Santa Monica, USA, 2009; pp. 119–121. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A.L. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G. Advances in the Methodology of Grounded Theory: Theoretical Sensitivity; Sociology Press: Mill Valley, CA, USA, 1978; pp. 36–54. [Google Scholar]

- Schröders, J.; Nichter, M.; San Sebastian, M.; Nilsson, M.; Dewi, F.S.T. ‘The Devil’s Company’: A Grounded Theory Study on Aging, Loneliness and Social Change Among ‘Older Adult Children’ in Rural Indonesia. Front. Sociol. 2021, 6, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, X.; Zhu, J.; Qin, Z. Risk factors identification of unsafe acts in deep coal mine workers based on grounded theory and HFACS. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 852612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2006; pp. 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, E.; Banner, D.; Estefan, A.; King-Shier, K. Being uncertain: Rural-living cardiac patients’ experience of seeking health care. Qual. Health Res. 2022, 32, 609–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, C.; Sukamdi, S.; Rijanta, R. Exploring migration hold Factors in climate change hazard-prone area using grounded theory study: Evidence from coastal Semarang, Indonesia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.D.; Yu, Q.; Yang, C.R. Barriers to speaking in class: An investigation by interview of undergraduates’ reticence. J. High. Educ. 2017, 38, 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X. Asian students' reticence revisited. System 2000, 28, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, B.; Kasim, Z.M.; Abdullah, A.N.; Rafik-Galea, S. Factors contributing to the use of conversational silence in academic discourse among Malaysian undergraduate students. 3L Lang. Linguist. Lit. 2018, 24, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakane, I. Silence and politeness in intercultural communication in university seminars. J. Pragmat. 2006, 38, 1811–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.F. From silence to talk: Cross-cultural ideas on students participation in academic group discussion. Engl. Specif. Purp. 1999, 18, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, L.-H.; Li, B. Silence as right, choice, resistance and strategy among Chinese “Me Generation” students: Implications for pedagogy. Discourse: Stud. Cult. Politics Educ. 2014, 35, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Q.Y. Understanding Chinese learners' willingness to communicate in a New Zealand ESL classroom: A multiple case study drawing on the theory of planned behavior. System 2013, 41, 740–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Q.; Gao, X.S. Reticence and willingness to communicate (WTC) of East Asian language learners. System 2016, 63, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, L. Does every student have a voice? Critical action research on equitable classroom participation practices. Lang. Teach. Res. 2012, 16, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.Y.; Zhou, J. The Correlative Factors for Chinese College Students’ Reticence in ESL (English as a Second Language) Classrooms. In Proceedings of the Sixth Northeast Asia International Symposium on Language, Literature and Translation, Datong, China, 10 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y.; Yue, Y.; Wang, X.; Luo, Z.; Li, Y. Negative silence in the classroom: A cross-sectional study of undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today 2022, 109, 105221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Moskal, M.; Schweisfurth, M. The social practice of silence in intercultural classrooms at a UK university. Comp. A J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2020, 52, 600–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedova, K.; Navratilova, J. Silent students and the patterns of their participation in classroom talk. J. Learn. Sci. 2020, 29, 681–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wong, D. Learning to be silent: Examining Chinese elementary students’ stories about why they do not speak in class. Lang. Cult. Curric. 2020, 33, 384–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L. Obstacles and opportunities for developing thinking through interaction in language classrooms. Think. Ski. Creat. 2011, 6, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Ni, Y.Y. Impact of curriculum reform: Evidence of change in classroom practice in mainland China. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2011, 50, 1–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y. An investigation into participation in classroom dialogue in mainland China. Cogent Educ. 2015, 2, 1065571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, K.D.; Ivala, E. Silence, voice, and “other languages”: Digital storytelling as a site for resistance and restoration in a South African higher education classroom. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2017, 48, 1164–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic. | Classification | Numbers | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 273 | 69.29% |

| Male | 121 | 30.71% | |

| Education Level | Freshman | 33 | 8.37% |

| Sophomore | 57 | 14.47% | |

| Junior | 278 | 70.56% | |

| Senior | 26 | 6.6% | |

| Major | Education | 198 | 50.25% |

| Preschool Education | 56 | 14.21% | |

| Special Education | 78 | 19.79% | |

| Educational Technology | 33 | 8.38% | |

| Physical Education | 29 | 7.37% |

| Number | Questions |

|---|---|

| 1 | Please tell us about the state of your professional classroom learning. |

| 2 | What is the overall state of classroom learning in your class? |

| 3 | How do you feel about your and your classmates’ silent behavior in class? |

| 4 | Why are you silent? |

| 5 | What steps do you think could be taken to improve classroom silence? |

| Original Statements (Partially Listed) | Labeling | Initial Categories | Major Categories |

|---|---|---|---|

| P27: Silence in the university classroom has become a common occurrence in professional classrooms today, and to me, this is a bad phenomenon. | Attitude | Subjective awareness | Silence cognition |

| P159: Classroom dialogue does not happen and teaching becomes a one-way activity. | Nature | ||

| P131: Silence in the classroom prevents students from learning better and also discourages teachers from teaching. | Hazard | ||

| P14: There are often no students willing to take the initiative to answer questions from the teacher. | Silence frequency | Objective perception | |

| P7: This phenomenon is becoming increasingly common and serious in university classrooms, and the reasons are varied. | Silence degree | ||

| P33: Classroom silence among university students is quite common. | Silence range | ||

| P27: Contemporary university students are always poorly motivated and engaged in the classroom. | Speaking activeness | Speaking situation | Silent behavior |

| P24: Some students’ classroom participation will be significantly higher if the instructor makes it clear that classroom presentations will be recorded into the overall final grade. | Speaking motivation | ||

| P9: I am not interested in the content taught, and I think I can pass the exam by casually learning. | Learn casually | Course concentration | |

| P78: They use these electronic devices to do things that are not related to the classroom. | Doing other assignments | ||

| P87: Students are more likely to think about whether they can answer well and thus defend their self-esteem with silence. | Self-efficacy | Self-confidence | Personality characteristics |

| P1: I think I can’t answer correctly so I don’t respond. | Speaking competence | ||

| P32: Some reduce the number of times they speak in public out of “saving face” or maintaining a low profile and modest attitude. | Modesty | Disposition | |

| P19: Students generally believe that speaking in class is a thing that “loses face”. | Lose face | ||

| P73: Students who are introverted and reticent may be reluctant to actively speak in class. | Introvert | ||

| P6: The fear of answering incorrectly is also a major reason that prevents students from speaking up. | Fearfulness | Speaking mentality | |

| P34: They are willing to think about the questions asked by the teacher but are not willing to take the initiative to answer them. | Willingness to speak | ||

| P12: They believe that speaking is not necessary for learning, | Speaking needs | ||

| P25: The lecture content format is not attractive and does not motivate students to answer questions. | Teaching situation | Course attractiveness | Classroom experience |

| P275: The teacher-student relationship is not harmonious, and students do not want to answer teachers’ questions. | Student-teacher relationship | ||

| P42: In my opinion, the teachers in the more active classes are generally interesting. | Teacher’s attributes | ||

| P30: If it weren’t for the “usual score” test in class, there would probably be no one in class. | Score incentive | ||

| P37: Lack of interest is a very important reason leading to students’ unwillingness to speak. | Classroom interest | ||

| P28: Students are reluctant to be the first to communicate and fear being alienated or rejected by the group. | Peer pressure | Peer influence | |

| P77: The classroom atmosphere is serious, and students are afraid to break the calmness and take the initiative to speak. | Classroom atmosphere | ||

| P162: The classroom seating arrangement does not facilitate discussion between the teacher and students. | Seating distribution | Interactive convenience | |

| P32: On a physical level, first, large classes make it difficult to create effective interactions. Second, the equipment in the classroom does not support effective dialogue. | Class size | ||

| Equipment constraints | |||

| P36: Exam-oriented education makes students accustomed to the classroom style of teacher lecturing. | Educational Inertia | Educational experience | Learning adjustment |

| P107: The long-time habit from elementary school to high school causes students to maintain their original listening habits and gradually develop classroom silence when they enter the university classroom. | Learning habits | ||

| P35: Basic education establishes the image of teacher authority and knowledge authority, which leads students to be afraid to challenge teachers and textbooks. | Authority awareness | ||

| P2: The strict entry and lenient exit of domestic universities also give students the capital to ignore the classroom. | Management system | University environment | |

| P24: The free and diffuse atmosphere of the university campus somewhat undermines students’ motivation to perform in class. | Learning atmosphere | ||

| P8: Most students simply require that they do not fail the exams in each course. | Self-development | Learning motivation | |

| P2: Because of the different levels of attention, university students are generally scattered and not motivated to study, so it makes sense that they are silent in class. | Learning emphasis |

| Core Category | Attribute | Dimension |

|---|---|---|

| Separation of cognition and practice | Cognitive level | High–low |

| Behavior state | Speaking–No speaking |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, F.; Yang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhu, A.-X. Behind the Silence of the Professional Classroom in Universities: Formation of Cognition-Practice Separation among University Students—A Grounded Theory Study in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14286. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114286

Xu F, Yang Y, Chen J, Zhu A-X. Behind the Silence of the Professional Classroom in Universities: Formation of Cognition-Practice Separation among University Students—A Grounded Theory Study in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(21):14286. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114286

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Fenghua, Yanru Yang, Junyuan Chen, and A-Xing Zhu. 2022. "Behind the Silence of the Professional Classroom in Universities: Formation of Cognition-Practice Separation among University Students—A Grounded Theory Study in China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 21: 14286. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114286

APA StyleXu, F., Yang, Y., Chen, J., & Zhu, A.-X. (2022). Behind the Silence of the Professional Classroom in Universities: Formation of Cognition-Practice Separation among University Students—A Grounded Theory Study in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 14286. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114286