Effects of Internet Adoption on Health and Subjective Well-Being of the Internal Migrants in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. SWB of the Rural–Urban Migrants

2.2. Health Status of the Rural–Urban Migrants

2.3. Internet, Social Capital, and Well-Being of the Rural–Urban Migrants

3. Research Design

3.1. Data Sources

3.2. Measurements

3.3. Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

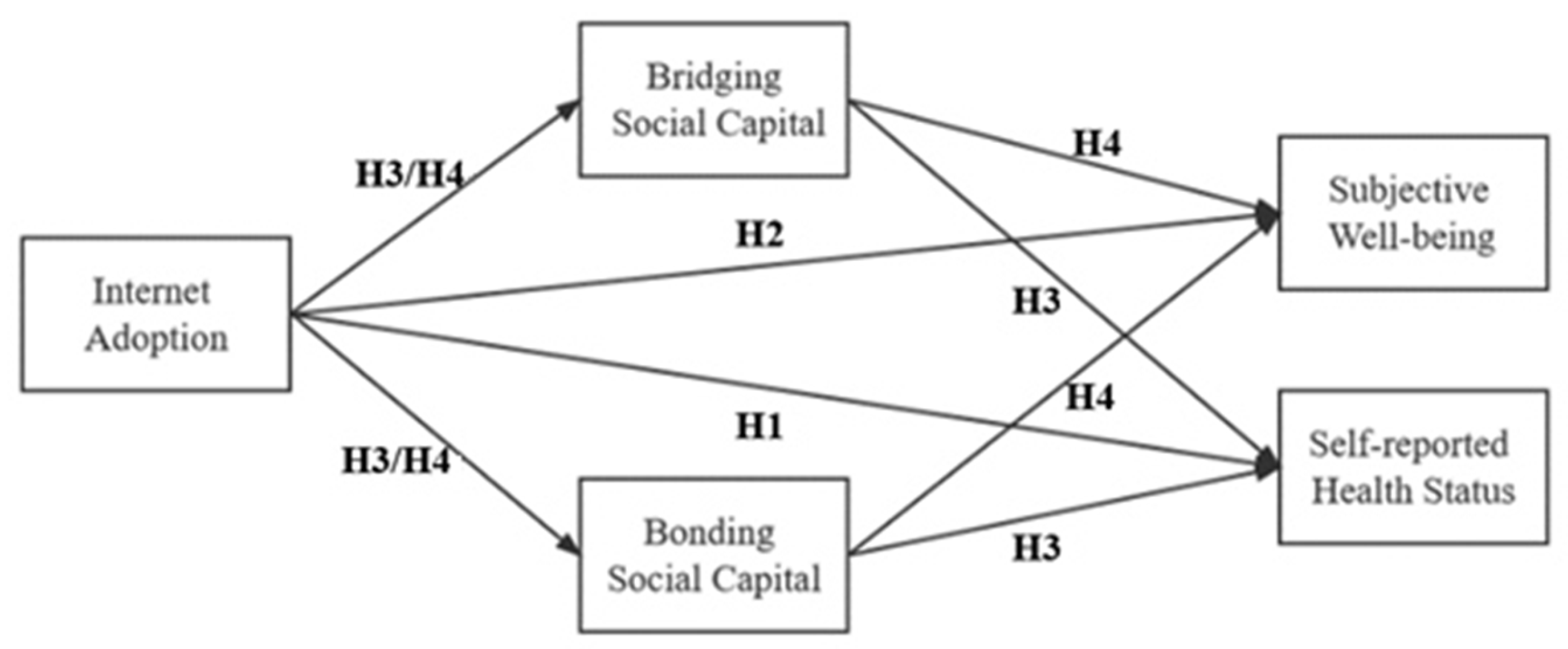

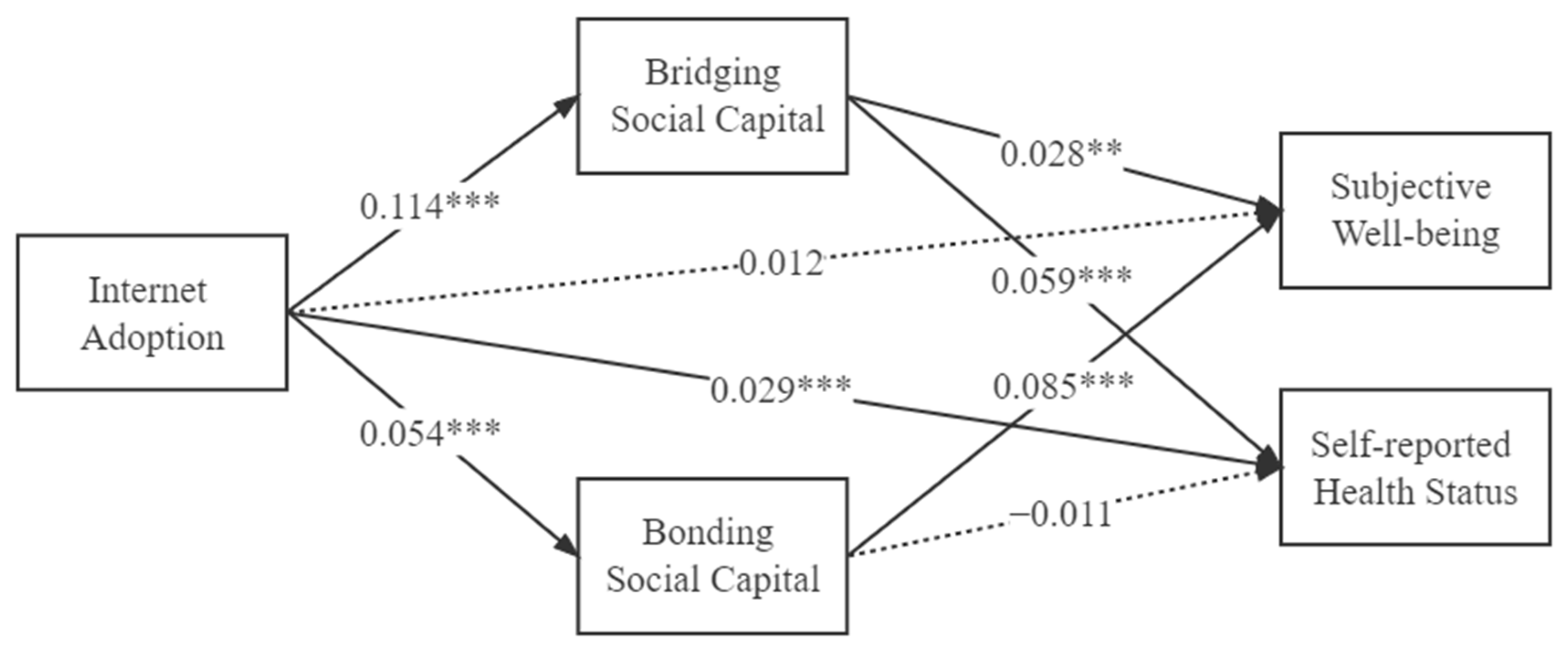

4.2. Structural Equation Modeling with Two Mediators

4.3. Heterogeneous Effect

4.3.1. Heterogeneous Effects of Gender

4.3.2. Heterogeneous Effects of Education Level

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | SWB | SRHS | BRSC | BOSC | SWB | SRHS |

| IA | 0.020 ** | 0.035 *** | 0.114 *** | 0.054 *** | 0.012 | 0.029 *** |

| (2.14) | (3.22) | (10.92) | (6.14) | (1.31) | (2.64) | |

| BRSC | 0.028 ** | 0.059 *** | ||||

| (2.10) | (3.80) | |||||

| BOSC | 0.085 *** | −0.011 | ||||

| (5.55) | (−0.61) | |||||

| Perceived social status | 0.207 *** | 0.139 *** | 0.069 *** | 0.048 *** | 0.201 *** | 0.135 *** |

| (15.49) | (9.61) | (5.07) | (4.17) | (15.06) | (9.37) | |

| Age | 0.003 *** | −0.017 *** | −0.006 *** | 0.001 | 0.003 *** | −0.017 *** |

| (3.76) | (−15.96) | (−6.13) | (1.47) | (3.86) | (−15.53) | |

| Education | 0.017 | 0.005 | 0.055 *** | 0.041 *** | 0.012 | 0.002 |

| (1.44) | (0.38) | (4.17) | (3.78) | (1.02) | (0.17) | |

| lnincome | −0.004 | 0.012 *** | 0.013 *** | 0.008 *** | −0.005 | 0.011 *** |

| (−1.27) | (3.37) | (4.06) | (2.92) | (−1.63) | (3.19) | |

| Marriage | 0.166 *** | 0.051 * | −0.202 *** | 0.061 *** | 0.166 *** | 0.063 ** |

| (6.59) | (1.82) | (−7.45) | (2.76) | (6.60) | (2.26) | |

| Female | 0.062 *** | −0.109 *** | −0.100 *** | 0.040 ** | 0.061 *** | −0.103 *** |

| (3.05) | (−4.64) | (−4.53) | (2.10) | (3.03) | (−4.36) | |

| Rural Hukou | −0.033 | 0.131 *** | −0.124 *** | −0.061 *** | −0.024 | 0.137 *** |

| (−1.34) | (4.69) | (−4.66) | (−2.74) | (−1.00) | (4.91) | |

| Year of survey fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Province-fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 2.963 *** | 4.016 *** | 2.125 *** | 1.611 *** | 2.767 *** | 3.909 *** |

| (30.73) | (37.00) | (20.34) | (18.29) | (27.56) | (34.21) | |

| Observations | 6212 | 6212 | 6212 | 6212 | 6212 | 6212 |

| R-squared | 0.095 | 0.156 | 0.174 | 0.050 | 0.103 | 0.159 |

References

- Easterlin, R.A. Subjective well-being and economic analysis: A brief introduction. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2001, 45, 225–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.X.; Mo, X.; Tang, C.Q. A study on the “income premium” effect of trade unions: An analysis based on the dynamic monitoring data of China’s floating population. Financ. Theory Pract. 2018, 39, 141–147. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Ren, Y. The reform of Hukou system in Chinese cities and the social inclusion of floating population. South China Popul. 2011, 26, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, J.; Gunatilaka, R. Great expectations? The subjective well-being of rural–urban migrants in China. World Dev. 2010, 38, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kemp, S. Book Reviews: Crime and Punishment in the Future Internet Digital: Frontier Technologies and Criminology in the Twenty-First Century. Eur. J. Probat. 2021, 13, 323–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotten, S.R.; Anderson, W.A.; McCullough, B.M. Impact of internet use on loneliness and contact with others among older adults: Cross-sectional analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013, 15, e2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, J.; Johnson, G.M. Internet use and psychological wellness during late adulthood. Can. J. Aging/La Rev. Can. Du Vieil. 2011, 30, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.; Chun, S.; Lee, S.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, J. Internet use and well-being in older adults. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2015, 18, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Lehto, X.Y. Internet use as a leisure pastime: Older adults’ subjective well-being and its correlates. Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2009, 9, 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelkes, O. Happier and less isolated: Internet use in old age. J. Poverty Soc. Justice 2013, 21, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, H.P.; Huang, Y.W.; Liu, L. Internet Use, Alienation and Rural Residents’ Well-Being: Micro-empirical Evidence Based on CGSS. J. Hainan Univ. 2021, 06, 86–94. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, C.C. Rural-urban migration and gender division of labor in transitional China. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2003, 27, 24–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Y.; Sohail, M.T. Short- and Long-Run Influence of Education on Subjective Well-Being: The Role of Information and Communication Technology in China. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 927562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Xue, S. Social networks and mental health outcomes: Chinese rural–urban migrant experience. J. Popul. Econ. 2020, 33, 155–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, S.C. An analysis of the influence of urban adaptability on floating population’s subjective well-being—A case study of the heilongjiang province. Popul. J. 2015, 4, 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.P.; Chen, L.; Yu, Z.P. Analysis of migrant workers’ life satisfaction and its influencing factors—Based on the data of the third survey on the social status of Chinese women. J. Jilin Norm. Univ. 2015, 06, 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, C. Absolute income, relative income and subjective well-being: Empirical test based on the sample data of urban and rural households in China. J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 35, 79–91. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Wu, F. The effect of neighbourhood social ties on migrants’ subjective wellbeing in Chinese cities. Habitat Int. 2017, 66, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potochnick, S.; Perreira, K.M.; Fuligni, A. Fitting in: The roles of social acceptance and discrimination in shaping the daily psychological well-being of Latino youth. Soc. Sci. Q. 2012, 93, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berry, J.W.; Hou, F. Acculturation, discrimination and wellbeing among second generation of immigrants in Canada. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2017, 61, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Chen, W. A Study on Social Media Use and Subjective Well-being among Urban Newcomers. Int. Press 2015, 37, 114–130. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, L.; Gao, F. Social media, social integration and subjective well-being among new urban migrants in China. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 786–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, Y.H.; Nie, X.Q.; Shi, M.F.; Wang, L.L.; Yuan, X.Q. The level of health literacy and influencing factors of migrant population from 2014 to 2016, China. Chin. J. Health Educ. 2018, 11, 963–967. [Google Scholar]

- Mou, J.; Griffiths, S.M.; Fong, H.; Dawes, M.G. Health of China’s rural–urban migrants and their families: A review of literature from 2000 to 2012. Br. Med. Bull. 2013, 106, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shi, X. Moving out but not for the better: Health consequences of interprovincial rural-urban migration in China. Health Econ. 2022, 31, 555–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.J.; Zhang, H.D.; Liu, H. Analysis of social influencing factors of self-assessment health of knowledge-based immigrants and migrant-type immigrants. J. Univ. Jinan 2019, 29, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.F.; Zhan, Y.H.; Armstrong, H. Population Health and Health Decisive Facotors. Chin. J. Health Educ. 2004, 02, 46–48. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, M. International social work research and health inequalities. J. Comp. Soc. Welf. 2006, 22, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Song, S. Do Nutrition and Health Affect Migrant Workers’ Incomes? Some Evidence from Beijing, China. China World Econ. 2010, 18, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, W.H.; Tsai, Y.-M. Social networking, hardiness and immigrant’s mental health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1986, 27, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paez, D.; Delfino, G.; Vargas-Salfate, S.; Liu, J.H.; Gil de Zúñiga, H.; Khan, S.; Garaigordobil, M. A longitudinal study of the effects of internet use on subjective well-being. Media Psychol. 2020, 23, 676–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraut, R.; Patterson, M.; Lundmark, V.; Kiesler, S.; Mukophadhyay, T.; Scherlis, W. Internet paradox: A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? Am. Psychol. 1998, 53, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Eijnden, R.J.; Meerkerk, G.-J.; Vermulst, A.A.; Spijkerman, R.; Engels, R.C. Online communication, compulsive Internet use, and psychosocial well-being among adolescents: A longitudinal study. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 44, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prizant-Passal, S.; Shechner, T.; Aderka, I.M. Social anxiety and internet use–A meta-analysis: What do we know? What are we missing? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 62, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantic, I. Online social networking and mental health. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2014, 17, 652–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adler, P.S.; Kwon, S.-W. Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, H.; Yasunobu, K. What is social capital? A comprehensive review of the concept. Asian J. Soc. Sci. 2009, 37, 480–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoloff, J.A.; Glanville, J.L.; Bienenstock, E.J. Women’s participation in the labor force: The role of social networks. Soc. Netw. 1999, 21, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, A. Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1998, 24, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y. A literature analysis of social capital’s transnational diffusion in Chinese sociology. Curr. Sociol. 2016, 64, 815–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M.S. The strength of weak ties. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 78, 1360–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Krämer, N.C.; Sauer, V.; Ellison, N. The Strength of Weak Ties Revisited: Further Evidence of the Role of Strong Ties in the Provision of Online Social Support. Soc. Media Soc. 2021, 7, 20563051211024958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krämer, N.C.; Rösner, L.; Eimler, S.C.; Winter, S.; Neubaum, G. Let the Weakest Link Go! Empirical Explorations on the Relative Importance of Weak and Strong Ties on Social Networking Sites. Societies 2014, 4, 785–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kawachi, I.; Berkman, L.F. Social ties and mental health. J. Urban Health 2001, 78, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sampson, R.J.; Raudenbush, S.W.; Earls, F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 1997, 277, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrabski, Á.; Kopp, M.; Kawachi, I. Social capital and collective efficacy in Hungary: Cross sectional associations with middle aged female and male mortality rates. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2004, 58, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Helliwell, J.F.; Putnam, R.D. The social context of well–being. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2004, 359, 1435–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, W.; Van Den Brink, H.M.; Van Praag, B. The compensating income variation of social capital. Soc. Indic. Res. 2007, 82, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, X.; Stanton, B.; Gong, J.; Fang, X.; Li, X. Personal Social Capital Scale: An instrument for health and behavioral research. Health Educ. Res. 2009, 24, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Gao, J.; Nie, X.; Dai, J.; Fu, H. Associations of individual social capital with subjective well-being and mental health among migrants: A survey from five cities in China. Int. Health 2019, 11, S64–S71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J. Online communication and adolescent social ties: Who benefits more from Internet use? J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2009, 14, 509–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trepte, S.; Dienlin, T.; Reinecke, L. Influence of social support received in online and offline contexts on satisfaction with social support and satisfaction with life: A longitudinal study. Media Psychol. 2015, 18, 74–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienlin, T.; Masur, P.K.; Trepte, S. Reinforcement or displacement? The reciprocity of FtF, IM, and SNS communication and their effects on loneliness and life satisfaction. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2017, 22, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gable, S.L.; Reis, H.T. Good news! Capitalizing on positive events in an interpersonal context. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 42, pp. 195–257. [Google Scholar]

- Figer, R.C. Internet Use and Social Capital: The Case of Filipino Migrants in Japan. Online J. Commun. Media Technol. 2014, 4, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooghe, M.; Oser, J. Internet, television and social capital: The effect of ‘screen time’ on social capital. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2015, 18, 1175–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jiang, J.; Song, J. Health Consequences of Online Social Capital among Middle-Aged and Older Adults in China. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2022, 17, 2277–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Shen, Y.; Liang, H.; Guo, R. Housing and Adult Health: Evidence from Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS). Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Kang, R. Temporal heterogeneity of the association between social capital and health: An age-period-cohort analysis in China. Public Health 2019, 172, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; Sun, C. Import trade liberalization and individual happiness: Evidence from Chinese general social survey 2010–2015. Appl. Econ. 2021, 53, 6535–6553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaqiang, Q. Reliability and Validity of Self-Rated General Health. Soc. Chin. J. Sociol. Shehui 2014, 34, 829–837. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, F.; Michaels, J.L.; Bell, S.E. Social Capital’s Influence on Environmental Concern in China: An Analysis of the 2010 Chinese General Social Survey. Sociol. Perspect. 2019, 62, 844–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macias, T.; Williams, K. Know Your Neighbors, Save the Planet:Social Capital and the Widening Wedge of Pro-Environmental Outcomes. Environ. Behav. 2016, 48, 391–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J. Likert data: What to use, parametric or non-parametric? Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2013, 4, 258–264. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, G. Likert scales, levels of measurement and the “laws” of statistics. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. Theory Prac. 2010, 15, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.B.; MacKinnon, D.P.; Tein, J.-Y. Tests of the three-path mediated effect. Organ. Res. Methods 2008, 11, 241–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Ye, B. Analysis of mediation effect: Method and model development. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 22, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Kou, D.; Shao, S.; Li, X.; Wang, W.; Zhang, C. Can urbanization process and carbon emission abatement be harmonious? New evidence from China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2018, 71, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, X.; Cao, J. Environmental regulation and carbon emission: The mediation effect of technical efficiency. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 236, 117599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wang, X.; Su, S.; Su, Y. How green technological innovation ability influences enterprise competitiveness. Technol. Soc. 2019, 59, 101136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year of Survey | Respondents | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 931 | 14.99% |

| 2013 | 973 | 15.66% |

| 2015 | 1020 | 16.42% |

| 2017 | 1645 | 26.48% |

| 2018 | 1643 | 26.45% |

| Variables | Freq. | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Female | ||

| Mean (SD) | 0.50 (0.50) | |

| Age | ||

| Mean (SD) | 41.83 (16.01) | |

| Subjective social class | ||

| Mean (SD) | 2.47 (0.84) | |

| =1 lowest class | 885 | 14.25% |

| =2 low class | 2040 | 32.84% |

| =3 middle class | 2822 | 45.43% |

| =4 high class | 426 | 6.86% |

| =5 highest class | 39 | 0.63% |

| Education | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.63 (1.20) | |

| =1 Illiterate | 306 | 4.93% |

| =2 Primary school | 827 | 13.31% |

| =3 Junior high school | 1700 | 27.37% |

| =4 Senior high school | 1406 | 22.63% |

| =5 College and above | 1973 | 31.76% |

| Rural Hukou | ||

| Mean (SD) | 0.54 (0.50) | |

| Marriage | ||

| Mean (SD) | 0.74 (0.44) | |

| Income (ln) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 9.01 (3.82) |

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Subjective Well-being | 3.87 | 0.80 | 1.00 | ||||

| 2. Self-reported Health Status | 3.88 | 0.97 | 0.18 *** | 1.00 | |||

| 3. Internet Adoption | 3.46 | 1.62 | 0.03 ** | 0.22 *** | 1.00 | ||

| 4. Bridging Social Capital | 2.55 | 0.93 | 0.05 *** | 0.16 *** | 0.33 *** | 1.00 | |

| 5. Bonding Social Capital | 2.21 | 0.73 | 0.11 *** | 0.04 *** | 0.13 *** | 0.39 *** | 1.00 |

| Path | Coef. | Robust SE | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | |||

| Internet Adoption→Subjective Well-being | 0.020 | 0.009 | 0.033 |

| Internet Adoption→Self-reported health status | 0.035 | 0.011 | 0.001 |

| Direct effect | |||

| Internet Adoption→Subjective Well-being | 0.012 | 0.009 | 0.190 |

| Internet Adoption→Self-reported health status | 0.029 | 0.011 | 0.008 |

| Internet Adoption→Bridging Social Capital | 0.114 | 0.010 | 0.000 |

| Internet Adoption→Bonding Social Capital | 0.054 | 0.009 | 0.000 |

| Bridging Social Capital→Subjective Well-being | 0.028 | 0.013 | 0.036 |

| Bonding Social Capital→Subjective Well-being | 0.085 | 0.015 | 0.000 |

| Bridging Social Capital→Self-reported health status | 0.059 | 0.015 | 0.000 |

| Bonding Social Capital→Self-reported health status | −0.011 | 0.018 | 0.542 |

| Indirect effect | Effect size | Bias-corrected LLCI | Bias-corrected ULCI |

| Internet Adoption→Bridging Social Capital→Subjective Well-being | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.005 |

| Internet Adoption→Bonding Social Capital→Subjective Well-being | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.004 |

| Internet Adoption→Bridging Social Capital→Self-reported health status | 0.007 | 0.003 | 0.009 |

| Internet Adoption→Bonding Social Capital→Self-reported health status | - | - | - |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | SWB | SRHS | BRSC | BOSC | SWB | SRHS |

| Female group | ||||||

| IA | 0.019 | 0.039 ** | 0.123 *** | 0.057 *** | 0.011 | 0.035 ** |

| (1.40) | (2.43) | (8.15) | (4.52) | (0.79) | (2.13) | |

| BRSC | 0.035 * | 0.034 | ||||

| (1.96) | (1.53) | |||||

| BOSC | 0.069 *** | 0.007 | ||||

| (3.12) | (0.26) | |||||

| Observations | 3122 | 3122 | 3122 | 3122 | 3122 | 3122 |

| R-squared | 0.098 | 0.160 | 0.186 | 0.062 | 0.104 | 0.161 |

| Male group | ||||||

| IA | 0.022 * | 0.032 ** | 0.104 *** | 0.050 *** | 0.015 | 0.024 |

| (1.69) | (2.11) | (7.20) | (4.04) | (1.17) | (1.59) | |

| BRSC | 0.017 | 0.085 *** | ||||

| (0.87) | (3.93) | |||||

| BOSC | 0.103 *** | −0.027 | ||||

| (4.75) | (−1.08) | |||||

| Observations | 3090 | 3090 | 3090 | 3090 | 3090 | 3090 |

| R-squared | 0.101 | 0.156 | 0.170 | 0.056 | 0.111 | 0.161 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | SWB | SRHS | BRSC | BOSC | SWB | SRHS |

| Illiterate group | ||||||

| IA | −0.019 | −0.011 | 0.151 ** | 0.077 | −0.025 | −0.026 |

| (−0.34) | (−0.18) | (2.13) | (1.57) | (−0.44) | (−0.40) | |

| BRSC | −0.032 | −0.044 | ||||

| (−0.60) | (−0.62) | |||||

| BOSC | 0.137 * | 0.274 *** | ||||

| (1.80) | (2.60) | |||||

| Observations | 306 | 306 | 306 | 306 | 306 | 306 |

| R-squared | 0.245 | 0.203 | 0.242 | 0.115 | 0.254 | 0.227 |

| Primary Education group | ||||||

| IA | 0.021 | 0.031 | 0.144 *** | 0.080 *** | 0.016 | 0.025 |

| (0.86) | (0.98) | (4.52) | (3.34) | (0.66) | (0.79) | |

| BRSC | −0.024 | 0.083 ** | ||||

| (−0.80) | (2.08) | |||||

| BOSC | 0.102 *** | −0.078 | ||||

| (2.60) | (−1.50) | |||||

| Observations | 827 | 827 | 827 | 827 | 827 | 827 |

| R-squared | 0.167 | 0.168 | 0.104 | 0.096 | 0.173 | 0.174 |

| Junior high school Education group | ||||||

| IA | 0.041 *** | 0.021 | 0.115 *** | 0.054 *** | 0.034 ** | 0.016 |

| (2.61) | (1.16) | (6.47) | (3.65) | (2.21) | (0.89) | |

| BRSC | 0.020 | 0.081 *** | ||||

| (0.83) | (2.81) | |||||

| BOSC | 0.072 ** | −0.087 ** | ||||

| (2.43) | (−2.45) | |||||

| Observations | 1700 | 1700 | 1700 | 1700 | 1700 | 1700 |

| R-squared | 0.128 | 0.182 | 0.127 | 0.051 | 0.134 | 0.188 |

| Senior high school Education group | ||||||

| IA | 0.000 | 0.050 ** | 0.119 *** | 0.046 ** | −0.013 | 0.041 * |

| (0.02) | (2.19) | (5.67) | (2.51) | (−0.66) | (1.80) | |

| BRSC | 0.059 * | 0.045 | ||||

| (1.87) | (1.44) | |||||

| BOSC | 0.135 *** | 0.063 * | ||||

| (3.95) | (1.77) | |||||

| Observations | 1406 | 1406 | 1406 | 1406 | 1406 | 1406 |

| R-squared | 0.091 | 0.209 | 0.176 | 0.044 | 0.111 | 0.214 |

| College degree and above group | ||||||

| IA | 0.017 | 0.023 | 0.065 *** | 0.023 | 0.014 | 0.019 |

| (0.77) | (0.86) | (2.72) | (1.01) | (0.60) | (0.69) | |

| BRSC | 0.039 | 0.074 ** | ||||

| (1.56) | (2.51) | |||||

| BOSC | 0.052 ** | −0.007 | ||||

| (1.99) | (−0.23) | |||||

| Observations | 1973 | 1973 | 1973 | 1973 | 1973 | 1973 |

| R-squared | 0.098 | 0.101 | 0.092 | 0.036 | 0.103 | 0.105 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhou, Y. Effects of Internet Adoption on Health and Subjective Well-Being of the Internal Migrants in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14460. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114460

Guo Y, Xu J, Zhou Y. Effects of Internet Adoption on Health and Subjective Well-Being of the Internal Migrants in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(21):14460. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114460

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Yihan, Junling Xu, and Yuan Zhou. 2022. "Effects of Internet Adoption on Health and Subjective Well-Being of the Internal Migrants in China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 21: 14460. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114460