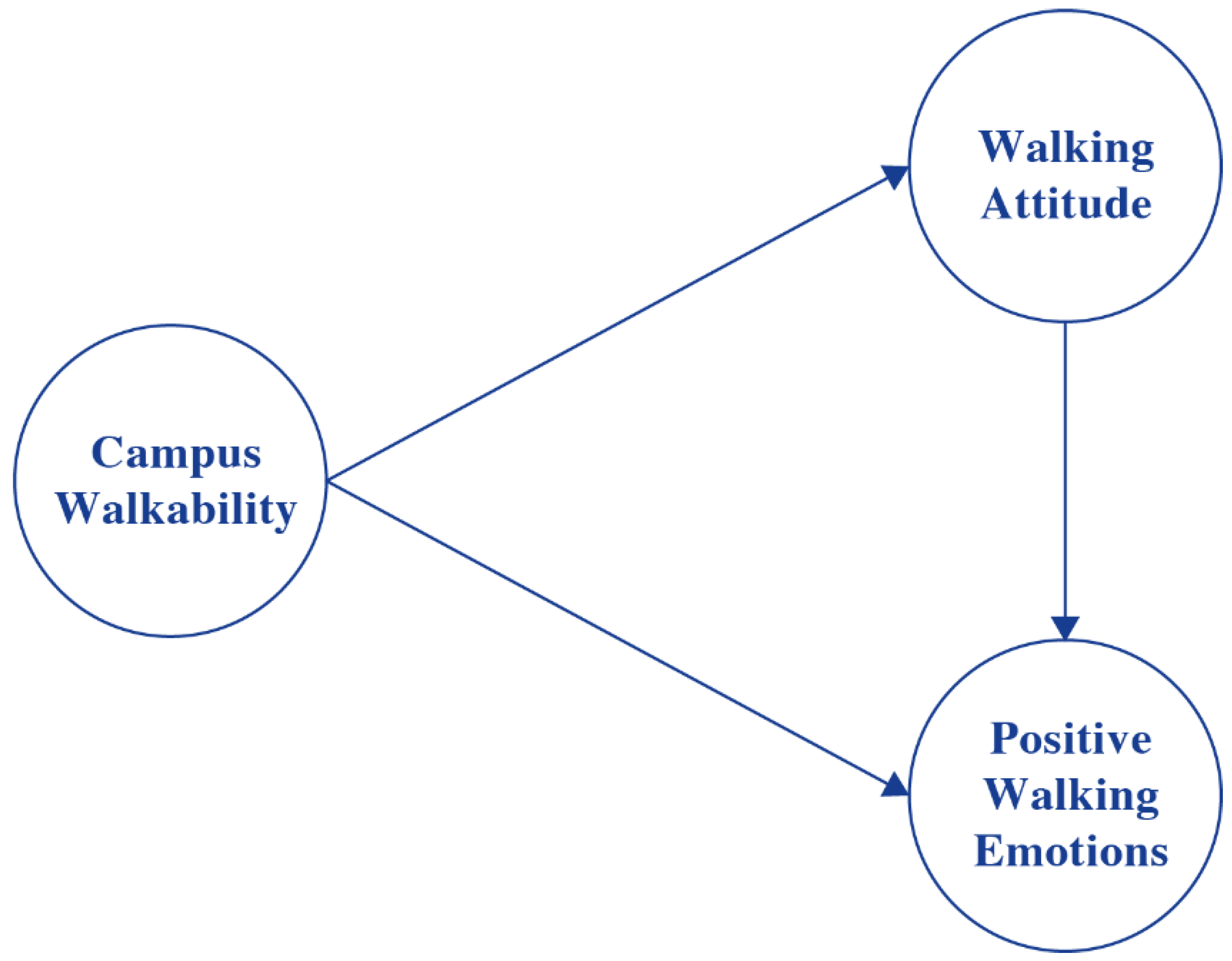

Association between Campus Walkability and Affective Walking Experience, and the Mediating Role of Walking Attitude

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

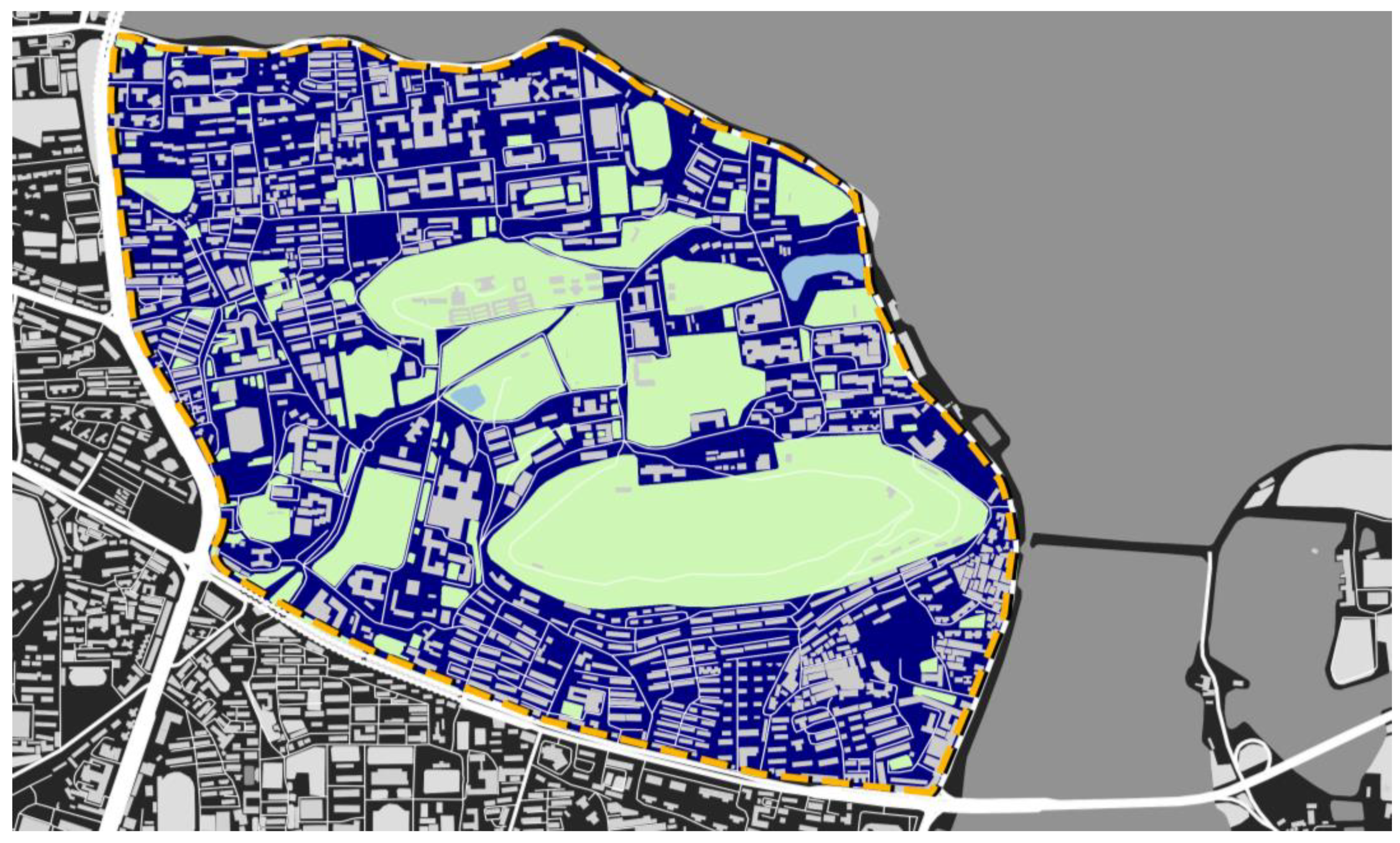

2.1. Study Site and Survey Instrument

2.2. Data Collection and Sample

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ramakreshnan, L.; Fong, C.S.; Sulaiman, N.M.; Aghamohammadi, N. Motivations and built environment factors associated with campus walkability in the tropical settings. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 749, 141457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battista, G.A.; Manaugh, K. Generating walkability from pedestrians’ perspectives using a qualitative GIS method. Travel Behav. Soc. 2019, 17, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, D.W.; Moudon, A.V.; Lee, J. The economic value of walkable neighborhoods. Urban Des. Int. 2012, 17, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyden, K.M. Social capital and the built environment: The importance of walkable neighborhoods. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 1546–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Fisher, T.; Feng, G. Assessing the rationality and walkability of campus layouts. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlKheder, S.; AlRukaibi, F. Enhancing pedestrian safety, walkability and traffic flow with fuzzy logic. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 701, 134454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southworth, M. Designing the walkable city. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2005, 131, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisson, S.B.; McClain, J.J.; Tudor-Locke, C. Campus walkability, pedometer-determined steps, and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity: A comparison of 2 university campuses. J. Am. Coll. Health 2008, 56, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Griffin, S.; Khaw, K.-T.; Wareham, N.; Panter, J. Longitudinal associations between built environment characteristics and changes in active commuting. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 458. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, N.; Cerin, E.; Leslie, E.; Coffee, N.; Frank, L.D.; Bauman, A.E.; Hugo, G.; Saelens, B.E.; Sallis, J.F. Neighborhood walkability and the walking behavior of Australian adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2007, 33, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, S.B.; Kaczynski, A.T.; Knight Wilt, J.; Stowe, E.W. Walkability 101: A Multi-Method Assessment of the Walkability at a University Campus. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 2158244020917954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handy, S.; Cao, X.; Mokhtarian, P. Correlation or causality between the built environment and travel behavior? Evidence from Northern California. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2005, 10, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahm, Y.; Yoon, H.; Choi, Y. The effect of built environments on the walking and shopping behaviors of pedestrians; A study with GPS experiment in Sinchon retail district in Seoul, South Korea. Cities 2019, 89, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okraszewska, R.; Jamroz, K.; Michalski, L.; Żukowska, J.; Grzelec, K.; Birr, K. Analysing ways to achieve a new Urban Agenda-based sustainable metropolitan transport. Sustainability 2019, 11, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghshenas, H.; Vaziri, M.; Gholamialam, A. Sustainable urban transport assessment in Asian cities. Curr. World Environ. 2013, 8, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Oreskovic, N.M.; Lin, H. How do changes to the built environment influence walking behaviors? A longitudinal study within a university campus in Hong Kong. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2014, 13, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bopp, M.; Behrens, T.K.; Velecina, R. Associations of weight status, social factors, and active travel among college students. Am. J. Health Educ. 2014, 45, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horacek, T.M.; White, A.A.; Greene, G.W.; Reznar, M.M.; Quick, V.M.; Morrell, J.S.; Colby, S.M.; Kattelmann, K.K.; Herrick, M.S.; Shelnutt, K.P.; et al. Sneakers and spokes: An assessment of the walkability and bikeability of US postsecondary institutions. J. Environ. Health 2012, 74, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Peachey, A.A.; Baller, S.L. Perceived Built Environment Characteristics of On-Campus and Off-Campus Neighborhoods Associated With Physical Activity of College Students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2015, 63, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczynski, A.T. Neighborhood walkability perceptions: Associations with amount of neighborhood-based physical activity by intensity and purpose. J. Phys. Act. Health 2010, 7, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi-Shekari, Z.; Moeinaddini, M.; Shah, M.Z. A pedestrian level of service method for evaluating and promoting walking facilities on campus streets. Land Use Policy 2014, 38, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinzeo, T.J.; Thayasivam, U.; Sledjeski, E.M. The development of the lifestyle and habits questionnaire-brief version: Relationship to quality of life and stress in college students. Prev. Sci. 2014, 15, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, E.; Sparling, P.B.; Owen, N. University campus settings and the promotion of physical activity in young adults: Lessons from research in Australia and the USA. Health Educ. 2001, 101, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, L.D.; Schmid, T.L.; Sallis, J.F.; Chapman, J.; Saelens, B.E. Linking objectively measured physical activity with objectively measured urban form: Findings from SMARTRAQ. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 28, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, J.; Ainsworth, B. Perceptions of environmental supports on the physical activity behaviors of university men and women: A preliminary investigation. J. Am. Coll. Health 2007, 56, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, J.A.; Phillips, D.A. Relationships between physical activity and the proximity of exercise facilities and home exercise equipment used by undergraduate university students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2005, 53, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roemmich, J.N.; Balantekin, K.N.; Beeler, J.E. Park-like campus settings and physical activity. J. Am. Coll. Health 2015, 63, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Garcia, J.; Castillo, I.; Sallis, J.F. Psychosocial and environmental correlates of active commuting for university students. Prev. Med. 2010, 51, 136–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, D.S.; Pereira, M.; Viana, C.M. Different destination, different commuting pattern? Analyzing the influence of the campus location on commuting. J. Transp. Land Use 2018, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birenboim, A.; Ben-Nun Bloom, P.; Levit, H.; Omer, I. The study of walking, walkability and wellbeing in immersive virtual environments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.T.H.; Li, T.E.; Schwanen, T.; Banister, D. People and their walking environments: An exploratory study of meanings, place and times. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2021, 15, 718–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauwers, L.; Leone, M.; Guyot, M.; Pelgrims, I.; Remmen, R.; den Broeck, K.; Keune, H.; Bastiaens, H. Exploring how the urban neighborhood environment influences mental well-being using walking interviews. Health Place 2021, 67, 102497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Powers, M.; Dye, C.; Vincent, E.; Padua, M. Walking in Your Culture: A Study of Culturally Sensitive Outdoor Walking Space for Chinese Elderly Immigrants. HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2021, 14, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loo, B.P.Y. Walking towards a happy city. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 93, 103078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, J.; Schwanen, T.; Van Acker, V.; Witlox, F. Travel and subjective well-being: A focus on findings, methods and future research needs. Transp. Rev. 2013, 33, 421–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, P.A. Walking (and cycling) to well-being: Modal and other determinants of subjective well-being during the commute. Travel Behav. Soc. 2019, 16, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Cervero, R. Travel and the built environment: A meta-analysis. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2010, 76, 265–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyck, D.; Cardon, G.; Deforche, B.; Owen, N.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I. Relationships between neighborhood walkability and adults’ physical activity: How important is residential self-selection? Health Place 2011, 17, 1011–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dyck, D.; Deforche, B.; Cardon, G.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I. Neighbourhood walkability and its particular importance for adults with a preference for passive transport. Health Place 2009, 15, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, P.; Murphy, M.; Mutrie, N. The health benefits of walking. In Walking; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ettema, D.; Smajic, I. Walking, places and wellbeing. Geogr. J. 2015, 181, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettema, D.; Gärling, T.; Olsson, L.E.; Friman, M. Out-of-home activities, daily travel, and subjective well-being. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2010, 44, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, B.; van den Berg, P.E.W.; van Wesemael, P.J.V.; Arentze, T.A. Individuals’ perception of walkability: Results of a conjoint experiment using videos of virtual environments. Cities 2022, 125, 103650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyck, D.; Cardon, G.; Deforche, B.; Sallis, J.F.; Owen, N.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I. Neighborhood SES and walkability are related to physical activity behavior in Belgian adults. Prev. Med. 2010, 50, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vliet, E.; Dane, G.; Weijs-Perrée, M.; van Leeuwen, E.; van Dinter, M.; van den Berg, P.; Borgers, A.; Chamilothori, K. The Influence of Urban Park Attributes on User Preferences: Evaluation of Virtual Parks in an Online Stated-Choice Experiment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Greenwald, M.J.; Zhang, M.; Walters, J.; Feldman, M.; Cervero, R.; Thomas, J. Measuring the Impact of Urban Form and Transit Access on Mixed Use Site Trip Generation Rates—Portland Pilot Study; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyck, D.; Cardon, G.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I. Which psychological, social and physical environmental characteristics predict changes in physical activity and sedentary behaviors during early retirement? A longitudinal study. PeerJ 2017, 5, e3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dyck, D.; Cardon, G.; Deforche, B.; Giles-Corti, B.; Sallis, J.F.; Owen, N.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I. Environmental and psychosocial correlates of accelerometer-assessed and self-reported physical activity in Belgian adults. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2011, 18, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Shepley, M.M. College campuses and student walkability: Assessing the impact of smartphone use on student perception and evaluation of urban campus routes. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keat, L.K.; Yaacob, N.M.; Hashim, N.R. Campus walkability in Malaysian public universities: A case-study of universiti malaya. Plan. Malays. 2016, 14, 101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, B.; Berg, P.E.W.V.D.; Van Wesemael, P.J.V.; Arentze, T.A. Empirical analysis of walkability using data from the Netherlands. Transp. Res. Part D 2020, 85, 102390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Mokhtarian, P.L.; Handy, S.L. Examining the Impacts of Residential Self-Selection on Travel Behaviour: A Focus on Empirical Findings. Transp. Rev. 2009, 29, 359–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Mokhtarian, P.L.; Handy, S.L. Do changes in neighborhood characteristics lead to changes in travel behavior? A structural equations modeling approach. Transportation 2007, 34, 535–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.-Y.; Zhu, X. From attitude to action: What shapes attitude toward walking to/from school and how does it influence actual behaviors? Prev. Med. 2016, 90, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Handy, S.L.; Mokhtarian, P.L. The influences of the built environment and residential self-selection on pedestrian behavior: Evidence from Austin, TX. Transportation 2006, 33, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paydar, M.; Fard, A.K.; Khaghani, M.M. Walking toward metro stations; the contribution of distance, attitudes, and perceived built environment. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Roux, A.V.D.; Auchincloss, A.H.; Rodriguez, D.A.; Brown, D.G. A spatial agent-based model for the simulation of adults’ daily walking within a city. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 40, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molin, E.; Mokhtarian, P.; Kroesen, M. Multimodal travel groups and attitudes: A latent class cluster analysis of Dutch travelers. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2016, 83, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Wang, D.; Guan, X. The built environment, travel attitude, and travel behavior: Residential self-selection or residential determination? J. Transp. Geogr. 2017, 65, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, R.; Merkies, R.; Damen, W.; Oirbans, L.; Massa, D.; Kroesen, M.; Molin, E. The role of travel-related reasons for location choice in residential self-selection. Travel Behav. Soc. 2021, 25, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerin, E.; Macfarlane, D.J.; Ko, H.-H.; Chan, K.-C.A. Measuring perceived neighbourhood walkability in Hong Kong. Cities 2007, 24, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerin, E.; Saelens, B.E.; Sallis, J.F.; Frank, L.D. Neighborhood environment walkability scale: Validity and development of a short form. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2006, 38, 1682–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saelens, B.E.; Sallis, J.F.; Black, J.B.; Chen, D. Neighborhood-Based Differences in Physical Activity: An Environment Scale Evaluation. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 1552–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saelens, B.E.; Sallis, J.F. Neighborhood environment walkability scale (NEWS). Am. J. Public Health 2002, 93, 73–81. [Google Scholar]

- Birenboim, A.; Dijst, M.; Ettema, D.; de Kruijf, J.; de Leeuw, G.; Dogterom, N. The utilization of immersive virtual environments for the investigation of environmental preferences. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 189, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Berg, P.E.W.V.D.; Ossokina, I.V.; Arentze, T.A. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems Comparing self-navigation and video mode in a choice experiment to measure public space preferences. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2022, 95, 101828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, P.E.W.; Liao, B.; Gorissen, S.; van Wesemael, P.J.V.; Arentze, T.A. The Relationship between Walkability and Place Attachment and the Mediating Role of Neighborhood-Based Social Interaction. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2022, 0739456X221118101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boles, J.S.; Johnston, M.W.; Hair, J.F., Jr. Role stress, work-family conflict and emotional exhaustion: Inter-relationships and effects on some work-related consequences. J. Pers. Sell.Sales Manag. 1997, 17, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M.R. Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2008, 6, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In Testing Structural Equation Models; SAGE: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1993; Volume 154, p. 136. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, K. Integration and Interaction: Redesign the Campus of Wuhan University, China. Master’s Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, C.; Chen, Y.; Duan, J.; Lu, Y.; Cui, J. Exploring the influence of attitudes to walking and cycling on commute mode choice using a hybrid choice model. J. Adv. Transp. 2017, 2017, 8749040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florek, M. No place like home: Perspectives on place attachment and impacts on city management. J. Town City Manag. 2011, 1, 346–354. [Google Scholar]

| Sample (N) | Sample (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male students | 151 | 45.2% |

| Female students | 183 | 54.8% |

| Education level | ||

| Undergraduate students | 324 | 97.0% |

| Graduate students | 10 | 3.0% |

| Length of campus residence | ||

| Less than one year | 151 | 45.2% |

| 1–2 years | 164 | 49.1% |

| More than 2 years | 19 | 5.7% |

| Cultural background | ||

| Native students | 309 | 92.5% |

| Non-native students | 25 | 7.5% |

| Total | 334 | 100% |

| Variables | Estimate |

| Campus walkability | |

| 1. About how long would it take to get from your dormitory to the nearest facilities listed below if you walked to them | |

| Classroom buildings | 0.75 |

| Library | 0.68 |

| Canteen | 0.66 |

| Snack bar | 0.67 |

| Fruits store | 0.74 |

| Delivery points | 0.76 |

| Supermarket | 0.56 |

| Department store | 0.68 |

| Gym | 0.75 |

| Outdoor sports space | 0.68 |

| Hospital | 0.59 |

| School bus stop | 0.60 |

| Green space | 0.69 |

| Composite Reliability | 0.901 |

| Average Variance Extracted | 0.505 |

| 2. Access to services | |

| Classroom buildings are within easy walking distance of my dormitory | 0.82 |

| Stores are within easy walking distance of my dormitory | 0.71 |

| Commercial areas are easy to arrive by public transportation | 0.76 |

| There are many places to go within easy walking distance of my dormitory | 0.84 |

| There are many slopes that make the road difficult to walk * | 0.57 |

| There are many obstacles that make the road difficult to walk * | 0.66 |

| There are many pedestrians on the street at peak hours * | 0.67 |

| There are many pedestrians on the street at non-peak hours * | 0.66 |

| Composite Reliability | 0.893 |

| Average Variance Extracted | 0.513 |

| 3. Streets on my campus | |

| The streets on my campus do not have many, or any, cul-de-sacs | 0.39 |

| The distance between intersections on my campus is usually short | 0.76 |

| There are many alternative routes for getting from place to place | 0.89 |

| Composite Reliability | 0.738 |

| Average Variance Extracted | 0.507 |

| 4. Places for walking | |

| There are sidewalks on most of the streets on my campus | 0.86 |

| Sidewalks are occupied by parked cars on my campus * | 0.21 |

| There is a strip that separates the streets from the sidewalks on my campus | 0.76 |

| Streets are well-lit at night | 0.62 |

| There are zebra crossings and traffic lights on a busy street | 0.67 |

| Walkable indoor spaces (with air-conditioning) are available on my campus | 0.79 |

| Streets and sidewalks are usually wet on my campus * | 0.81 |

| There are rest facilities, such as benches | 0.87 |

| Composite Reliability | 0.892 |

| Average Variance Extracted | 0.529 |

| 5. Campus surroundings | |

| There are trees along the streets on my campus | 0.43 |

| There are many interesting things to look at while walking on my campus | 0.82 |

| There are many green spaces on my campus | 0.91 |

| There are attractive buildings on my campus | 0.91 |

| Air pollution is usually high on my campus * | 0.43 |

| Composite Reliability | 0.842 |

| Average Variance Extracted | 0.540 |

| 6. Safety from traffic | |

| There is so much traffic along the nearby street that it makes it difficult to walk * | 0.65 |

| The speed of traffic on most nearby streets is usually slow (30 km/h or less) | 0.22 |

| Most drivers exceed the posted speed limits while driving on my campus * | 0.68 |

| There are many parked cars on nearby streets that which makes it difficult to cross * | 0.92 |

| There are many passing cars on nearby streets that it is frightening to cross * | 0.94 |

| Composite Reliability | 0.833 |

| Average Variance Extracted | 0.533 |

| Affective walking experience (positive walking emotions) | |

| I felt happy | 0.83 |

| I felt annoyed * | 0.11 |

| I felt comfortable | 0.95 |

| I felt secure | 0.59 |

| Composite Reliability | 0.768 |

| Average Variance Extracted | 0.514 |

| To | Walking Attitude | Positive Walking Emotions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| From | Direct | Total | Direct | Total |

| Campus walkability | 0.283 | 0.283 | 0.470 | 0.570 |

| Walking attitude | 0.521 | 0.521 | ||

| Undergraduate students | −0.221 | −0.191 | ||

| Length of campus residence | 0.206 | 0.217 | ||

| Native students | −0.539 | −0.142 | ||

| R2 | 0.612 | 0.185 | ||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.418 | 0.185 | ||

| Chi-square/df | 2.930 | |||

| Goodness-of-fit index | 0.905 | |||

| Normed fit index | 0.925 | |||

| RMSEA | 0.066 | |||

| SRMR | 0.078 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liao, B.; Xu, Y.; Li, X.; Li, J. Association between Campus Walkability and Affective Walking Experience, and the Mediating Role of Walking Attitude. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14519. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114519

Liao B, Xu Y, Li X, Li J. Association between Campus Walkability and Affective Walking Experience, and the Mediating Role of Walking Attitude. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(21):14519. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114519

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiao, Bojing, Yifan Xu, Xiang Li, and Ji Li. 2022. "Association between Campus Walkability and Affective Walking Experience, and the Mediating Role of Walking Attitude" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 21: 14519. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114519

APA StyleLiao, B., Xu, Y., Li, X., & Li, J. (2022). Association between Campus Walkability and Affective Walking Experience, and the Mediating Role of Walking Attitude. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 14519. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114519