Assessing Quality of Life with Community Dwelling Elderly Adults: A Mass Survey in Taiwan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Measures

- (1)

- Sociodemographic: gender, age, education level, living arrangement, and financial situation.

- (2)

- The Taiwanese version of the WHOQOL-BREF divided into four domains: physical health (7 items), psychological health (6 items), social relationships (4 items), and environmental factors (9 items).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.3.1. Reliability and Validity

2.3.2. Analytical Strategies

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

3.2. Domain Findings

3.3. Item Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.1.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

4.1.2. Relative Domains

4.1.3. Items

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.2.1. Strengths

4.2.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Ageing and Health. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- U.S. Census Bureau International Programs. An Aging World. 2020. Available online: https://mtgisportal.geo.census.gov/arcgis/apps/MapSeries/index.html?appid=3d832796999042daae7982ff36835e2e (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- U.S. Census Bureau International Programs. Demographics of Aging. 2001. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2001/demo/p95-01-1.html (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- National Development Council, Taiwan. Population Estimates of the Republic of China (1960–2070). 2020. Available online: https://popproj.ndc.gov.tw/chart.aspx?c=10&uid=66&pid=60 (accessed on 24 February 2022).

- Nascimento, C.M.C.; Ayan, C.; Cancela, J.M.; Pereira, J.R.; Andrade, L.P.D.; Garuffi, M.; Gobbi, S.; Stella, F. Exercícios físicos generalizados capacidade funcional e sintomas depressivos em idosos brasileiros. Rev. Bras. Cineantropom. Desempenho. Hum. 2013, 15, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.J.; Guo, C.Z.; Ping, W.W.; Tan, Z.J.; Guo, Y.; Zheng, J.Z. A community-based study of quality of life and depression among older adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL). Position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 41, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netuveli, G.; Blane, D. Quality of life in older ages. Br. Med. Bull. 2008, 85, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jeste, D.V.; Savla, G.N.; Thompson, W.K.; Vahia, I.V.; Glorioso, D.K.; Martin, A.S.; Palmer, B.W.; Rock, D.; Golshan, S.; Kraemer, H.C.; et al. Association between older age and more successful aging: Critical role of resilience and depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 2013, 170, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Adami, I.; Foukarakis, M.; Ntoa, S.; Partarakis, N.; Stefanakis, N.; Koutras, G.; Kutsuras, T.; Ioannidi, D.; Zabulis, X.; Stephanidis, C. Monitoring health parameters of elders to support independent living and improve their quality of life. Sensors 2021, 21, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.Y.; Li, Y.P.; Lin, S.I.; Chen, C.H. Measurement equivalence across gender and education in the WHOQOL-BREF for community dwelling elderly Taiwanese. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2016, 28, 1375–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahar, S.; Kamaruddin, N.S.; Badrasawi, M.; Sakian NI, M.; Manaf, Z.A.; Yassin, Z.; Joseph, L. Effectiveness of exercise and protein supplementation intervention on body composition, functional fitness, and oxidative stress among elderly Malays with sarcopenia. Clin. Interv. Aging 2013, 8, 1365–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prior, S.J.; Ryan, A.S.; Blumenthal, J.B.; Watson, J.M.; Katzel, L.I.; Goldberg, A.P. Sarcopenia is associated with lower skeletal muscle capillarization and exercise capacity in older adults. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2016, 17, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moore, M.; Warburton, J.; O’Halloran, P.D.; Shields, N.; Kingsley, M. Effective community-based physical activity interventions for older adults living in rural and regional areas: A Systematic review. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2016, 24, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynou, L.; Hernández-Pizarro, H.M.; Errea Rodríguez, M. The Association of Physical in Activity with Mental Health. Differences between elder and younger populations: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhao, X.; Sun, Y.; Xie, H.; Jia, J.; Su, Y.; Li, Y. Association between social support and health-related quality of life among Chinese rural elders in nursing homes: The mediating role of resilience. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dijk, H.M.; Cramm, J.M.; Birnie, E.; Nieboer, A.P. Effects of an integrated neighborhood approach on older people’s health-related quality of life and well-being. BMC Res. Notes 2016, 9, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ibrahim, N.; Din, N.-C.; Ahmad, M.; Ghazali, S.-E.; Said, Z.; Shahar, S.; Ghazali, A.R.; Razali, R. Relationships between social support and depression, and quality of life of the elderly in a rural community in Malaysia. Asia Pac. Psychiatry 2013, 5, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardes, S.F.; Matos, M.; Goubert, L. Older adults’ preferences for formal social support of autonomy and dependence in pain: Development and validation of a scale. Eur. J. Ageing 2017, 14, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lin, Y.Y.; Huang, C.S. Aging in Taiwan: Building a society for active aging and aging in place. Gerontologist 2016, 56, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yao, G.; Cheng, C.W.; Yu, C.F.; Wang, J.D. Development and verification of validity and reliability of the WHOQOL-BREF Taiwan version. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2002, 101, 342–351. [Google Scholar]

- Molzahn, A.E.; Kalfoss, M.; Makaroff, K.S.; Skevington, S.M. Comparing the importance of different aspects of quality of life to older adults across diverse cultures. Age Ageing 2011, 40, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Urzúa, A.; Miranda-Castillo, C.; Caqueo-Urízar, A.; Mascayano, F. Do Cultural values affect quality of life evaluation? Soc. Indic. Res. 2012, 144, 1295–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.C.K. Computer Assisted Telephone Interviewing (CATI) for health surveys in public health surveillance: Methodological issues and challenges ahead. Chronic Dis. Can 2004, 25, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: New York, NY, USA, 1988; p. 345. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. Survey on the Status of the Elderly. 2017. Available online: https://dep.mohw.gov.tw/dos/lp-5095-113-xCat-y106.html (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Jöreskog, K.G.; Söbom, D. LISREL 8. Structural Equation Modeling with the SIMPLIS Command Language; Scientific Software International: Lincolnwood, IL, USA, 1993; p. 246. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.E.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998; p. 225. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y.; Phillips, L.W. Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Adm. Sci. Q. 1991, 36, 421–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.R.; Larcker, F.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neter, J.; Wasserman, W.; Kutner, M.H. Applied Linear Regression Models, 2nd ed.; Richard D. Irwin, Inc.: Homewood, IL, USA, 1989; p. 156. [Google Scholar]

- Chief Accounting Office of the Executive Yuan. Survey on the Status of Living alone Elderly in Statistics Bulletin. 2021. Available online: https://www.dgbas.gov.tw/public/Data/17216659PNHRMIOU.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- von Steinbϋchel, N.; Lischetzke Tanja Gurny, M.; Eid, M. Assessing quality of life in older people: Psychometric properties of the WHOQOL-BREF. Eur. J. Ageing 2006, 3, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Han, X.; Xiao, Q.; Li, S.; Feldman, M.W. Family structure and quality of life of elders in rural China: The role of the new rural social pension. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2015, 27, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhou, J.; Hearst, N. Health-related quality of life of among elders in rural China: The effect of widowhood. Qual. Life Res. 2016, 25, 3087–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Farzianpour, F.; Foroushani, A.R.; Badakhshan, A.; Gholipour, M. The relationship between quality of life with demographic variables of elderly in Golestan Province-Iran. Sci. Res. 2015, 7, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gobbens, R.J.; Remmen, R. The effects of sociodemographic factors on quality of life among people aged 50 years or older are not unequivocal: Comparing SF-12, WHOQOL-BREF, and WHOQOL-OLD. Clin. Interv. Aging 2019, 14, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Devraj, S.; D’mello, M.K. Determinants of quality of life among the elderly population in urban areas of Mangalore, Karnataka. J. Geriatr. Ment. Health 2019, 6, 94–98. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.H.; Xu, H.; Lee, B. Gender differences in quality of life among community-dwelling older adults in low and middle-income countries: Results from the Study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE). BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, H.H.; Lin, Z.Y. The study on the social supports and life satisfaction for elderly in Nantou County. J. Lib. Arts Soc. Sci. 2012, 6, 100–127. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Yang, Y. A study on friendship support and well-being of the elderly—Taking the Taipei elderly service center as an example. Community Dev. Q. 2006, 113, 208–224. [Google Scholar]

- Khaje-Bishak, Y.; Payahoo, L.; Pourghasem, B.; Jafarabadi, M.A. Assessing the quality of life in elderly people and related factors in Tabriz, Iran. J. Caring Sci. 2014, 3, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Campos, A.C.V.; e Ferreira, E.F.; Vargas, A.M.D.; Albala, C. Aging, Gender and Quality of Life (AGEQOL) study: Factors associated with good quality of life in older Brazilian community-dwelling adults Ana Cristina Viana. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2014, 12, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Momenabadi, V.; Kaveh, M.H.; Nazari, M.; Ghahremani, L. Socio-demographic determinants of quality of life among older people, a population-based study. Elder. Health J. 2018, 4, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Health Insurance Agency. National Health Insurance Satisfaction. 2019. Available online: https://www.mohw.gov.tw/cp-4251-50316-1.html (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. Long Term Care Ten Year Plan 2.0. 2016. Available online: https://www.ey.gov.tw/Page/5A8A0CB5B41DA11E/dd4675bb-b78d-4bd8-8be5e3d6a6558d8d (accessed on 18 July 2021).

- Tao, Y.C.; Shen, Y. The influence of social support on the physical and mental health of rural elderly. Popul. Econ. 2014, 3, 3–14. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.C.; Yao, G.; Hu, S.C.; Wang, J.D. Depression affects the scores of all facets of the WHOQOL-BREF and may mediate the effects of physical disability among community-dwelling older adults. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chammem, R.; Domi, S.; Vecchia, C.D.; Gilbert, T.; Schott, A.M. Experience and perceptions of changes in the living environment by older people losing their autonomy: A qualitative study in the Caribbean. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 743–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goes, M.; Lopes, M.; Marôco, J.; Oliveira, H.; Fonseca, C. Psychometric properties of the WHOQOL-BREF(PT) in a sample of elderly citizens. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2021, 19, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, P.; Li, N.; Hau, K.T.; Liu, C.; Lu, Y. Quality of life of Chinese urban community residents: A psychometric study of the mainland Chinese version of the WHOQOL-BREF. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2012, 12, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- National Health Administration. Community Health Creation Center. 2019. Available online: https://www.hpa.gov.tw/Pages/Detail.aspx?nodeid=580&pid=905 (accessed on 8 July 2021).

- Lu, Y.H. General Arrangement of Subsidies for Public Transportation in All Counties and Cities in Taiwan. 2021. Available online: https://health.businessweekly.com.tw/AArticle.aspx?ID=ARTL003004754&p=4 (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Hsu, H.C. Associations of city-level active aging and age friendliness with well-being among older adults aged 55 and over in Taiwan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.S.; Hsieh, C.C.; Cheng, H.S.; Tseng, T.J.; Su, S.C. Fitness and successful aging in Taiwanese older adults. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150389. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, Y.C.; Wu, C.L.; Liu, H.T. Effect of a multi-disciplinary active aging intervention among community elders. Medicine 2021, 100, e28314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Reliability and Validity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lambda Loading | Z-Value | Composite Reliability | Cronbach’s Alpha | |

| Physical health | 0.85 | 0.84 | ||

| E3: Activities of daily living | 0.53 | − 1 | ||

| E4: Dependence on medicinal substances and medical aids | 0.48 | 26.8 | ||

| E10: Energy and fatigue | 0.77 | 29.2 | ||

| E15: Mobility | 0.77 | 29.6 | ||

| E16: Pain and discomfort | 0.54 | 26.7 | ||

| E17: Sleep and rest | 0.82 | 28.6 | ||

| E18: Work capacity | 0.77 | 28.7 | ||

| Psychological health | 0.82 | 0.81 | ||

| E5: Positive feelings | 0.71 | − | ||

| E6: Spirituality/Religion/Personal beliefs | 0.68 | 34.3 | ||

| E7: Thinking/learning/memory/concentration | 0.73 | 34.3 | ||

| E11: Bodily image and appearance | 0.58 | 29.3 | ||

| E19: Self-esteem | 0.74 | 32.3 | ||

| E26: Negative feelings | 0.46 | 22 | ||

| Social relationships | 0.70 | 0.70 | ||

| E20: Personal relationships | 0.71 | − | ||

| E21: Sexual activity | 0.48 | 22.4 | ||

| E22: Social support | 0.61 | 24.3 | ||

| E27: Social Respect | 0.64 | 25.8 | ||

| Environmental factors | 0.79 | 0.79 | ||

| E8: Freedom/physical safety/security | 0.67 | − | ||

| E9: Physical environment (pollution/noise/traffic/climate) | 0.47 | 24.8 | ||

| E12: Financial resources | 0.62 | 27.2 | ||

| E13: Opportunities for acquiring new information and skills | 0.60 | 27.4 | ||

| E14: Participation in and opportunities for recreation/leisure activities | 0.54 | 28.6 | ||

| E23: Home environment | 0.56 | 24 | ||

| E24: Health and social care: accessibility and quality | 0.48 | 21.1 | ||

| E25: Transport | 0.54 | 24 | ||

| E28: Food availability | 0.43 | 21.8 | ||

| Sociodemographic Variables | Counts | Percentage (n = 1078) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Men | 420 | 39.0% |

| Women | 658 | 61.0 % |

| Age | ||

| 65–74 years old | 633 | 58.7% |

| 75–84 years old | 325 | 30.1% |

| 85 years old above | 120 | 11.1% |

| Education Level | ||

| Illiterate | 93 | 8.6% |

| Elementary school | 331 | 30.7% |

| Secondary school | 113 | 10.5% |

| Senior High School | 218 | 20.2% |

| University | 286 | 26.5% |

| Master’s degree or above | 37 | 3.4% |

| Living Arrangement | ||

| Living alone | 125 | 11.6% |

| Live with spouse | 281 | 26.1% |

| Living with regular family members | 666 | 61.8% |

| Other | 6 | 0.6% |

| Financial situation | ||

| Well off | 77 | 7.1% |

| Roughly enough | 857 | 79.5% |

| Struggling | 144 | 13.4% |

| Predictor | Quality of Life Assessment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stand. Estimate | SE | t | p | |

| Gender (ref: Men) | ||||

| Women | 0.12 * | 0.04 | 2.41 | 0.016 |

| Age (ref: 65–74 years old) | ||||

| 75–84 years oldd | 0.09 | 0.04 | 1.57 | 0.116 |

| 85 years old above | 0.18 * | 0.06 | 2.25 | 0.025 |

| Education level (ref: illiterate) | ||||

| Elementary school | 0.30 ** | 0.07 | 3.25 | 0.001 |

| Secondary school | 0.27 * | 0.08 | 2.45 | 0.015 |

| Senior High School | 0.39 ** | 0.08 | 3.78 | <0.001 |

| University | 0.30 ** | 0.08 | 2.93 | 0.003 |

| Master’s degree or above | 0.86 ** | 0.12 | 5.36 | <0.001 |

| Living Arrangement (ref: living alone) | ||||

| Live with only two spouses | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.22 | 0.825 |

| Living with regular family members | −0.03 | 0.06 | −0.40 | 0.69 |

| Other | 0.13 | 0.24 | 0.40 | 0.69 |

| Financial situation (ref: well off) | ||||

| Roughly enough | −0.27 ** | 0.07 | −2.88 | 0.004 |

| Struggling | −0.48 ** | 0.09 | −3.98 | <0.001 |

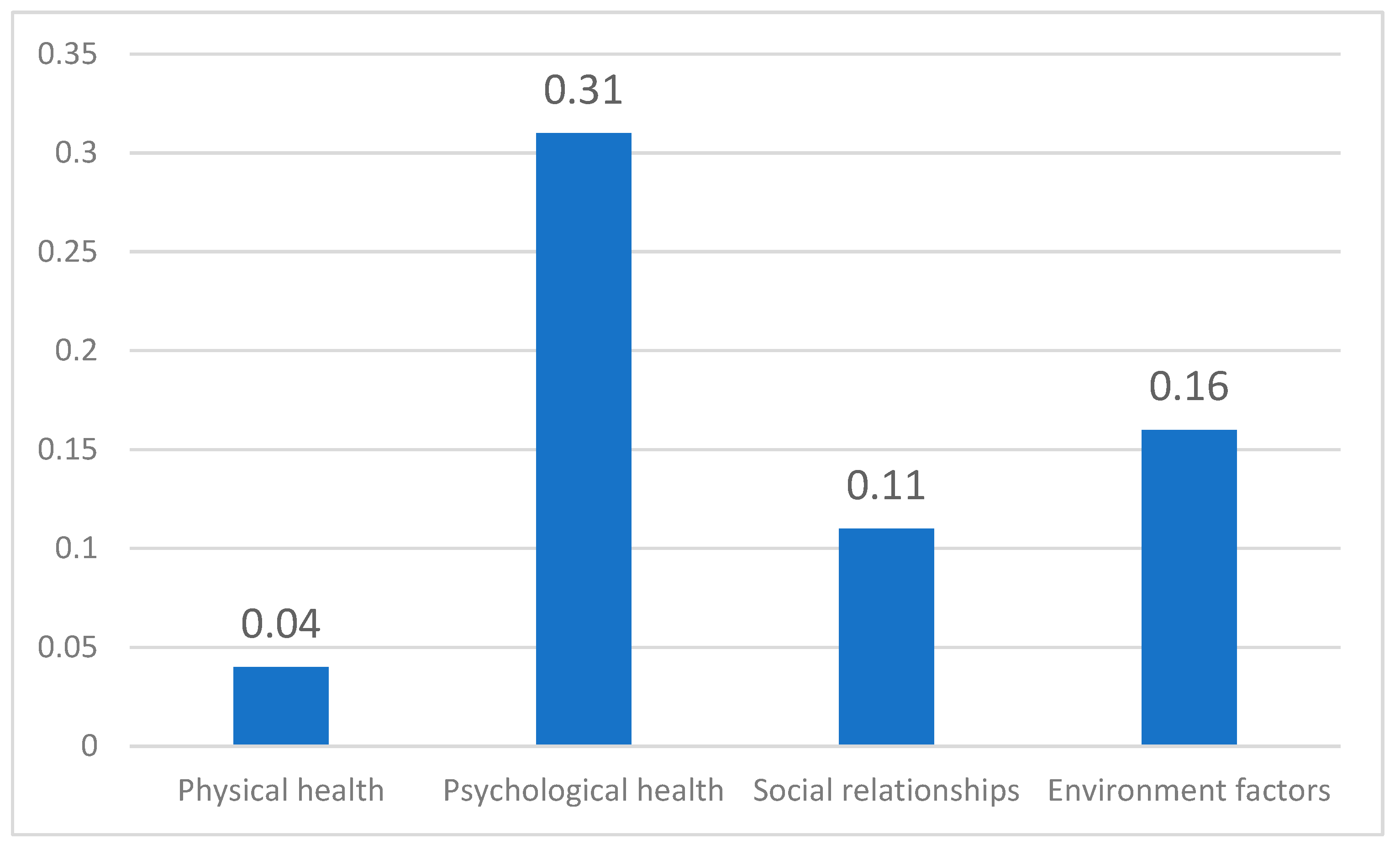

| Physical health | 0.04 | 0.01 | 1.19 | 0.233 |

| Psychological health | 0.31 ** | 0.01 | 7.21 | <0.001 |

| Social relationships | 0.11 ** | 0.01 | 3.06 | 0.002 |

| Environmental Factors | 0.16 ** | 0.01 | 3.97 | <0.001 |

| R2 | 0.412 | |||

| Predictor | Quality of Life Assessment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stand. Estimate | ||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Physical health | ||||

| E3: Activities of daily living | −0.01 | |||

| E4: Dependence on medicinal substances and medical aids | 0.05 | |||

| E10: Energy and fatigue | 0.19 ** | |||

| E15: Mobility | 0.04 | |||

| E16: Pain and discomfort | 0.08 * | |||

| E17: Sleep and rest | 0.15 ** | |||

| E18: Work Capacity | 0.14 ** | |||

| Psychological health | ||||

| E5: Positive feelings | 0.32 ** | |||

| E6: Spirituality/Religion/Personal beliefs | 0.13 ** | |||

| E7: Thinking/learning/memory/concentration | 0.04 | |||

| E11: Bodily image and appearance | 0.10 ** | |||

| E19: Self-esteem | 0.14 ** | |||

| E26: Negative feelings | 0.06 * | |||

| Social relationships | ||||

| E20: Personal relationships | 0.19 ** | |||

| E21: Sexual activity | 0.12 ** | |||

| E22: Social support | 0.11 ** | |||

| E27: Social Respect | 0.24 ** | |||

| Environmental factors | ||||

| E8: Freedom/physical safety/security | 0.11 ** | |||

| E9: Physical environment (pollution/noise/traffic/climate) | 0.07 * | |||

| E12: Financial resources | 0.20 ** | |||

| E13: Opportunities for acquiring new information and skills | 0.16 ** | |||

| E14: Participation in and opportunities for recreation/leisure activities | 0.07 ** | |||

| E23: Home environment | 0.08 ** | |||

| E24: Health and social care: accessibility and quality | 0.03 | |||

| E25: Transport | 0.06 | |||

| E28: Food availability | 0.11 ** | |||

| R2 | 0.253 | 0.360 | 0.240 | 0.329 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chi, Y.-C.; Wu, C.-L.; Liu, H.-T. Assessing Quality of Life with Community Dwelling Elderly Adults: A Mass Survey in Taiwan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14621. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214621

Chi Y-C, Wu C-L, Liu H-T. Assessing Quality of Life with Community Dwelling Elderly Adults: A Mass Survey in Taiwan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(22):14621. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214621

Chicago/Turabian StyleChi, Ying-Chen, Chen-Long Wu, and Hsiang-Te Liu. 2022. "Assessing Quality of Life with Community Dwelling Elderly Adults: A Mass Survey in Taiwan" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 22: 14621. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214621

APA StyleChi, Y.-C., Wu, C.-L., & Liu, H.-T. (2022). Assessing Quality of Life with Community Dwelling Elderly Adults: A Mass Survey in Taiwan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 14621. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214621