Trait Acceptance Buffers Aggressive Tendency by the Regulation of Anger during Social Exclusion

Abstract

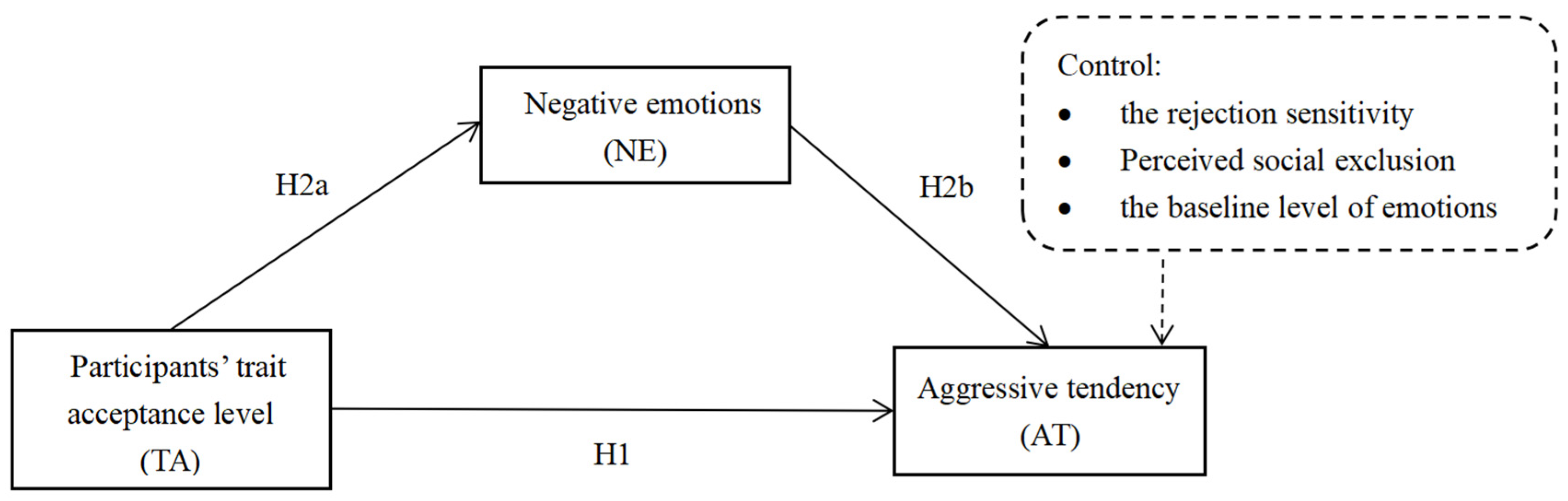

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurements

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Assessment of Common Method Variance

3. Results

3.1. Correlation Analysis

3.2. Regression Analysis

3.3. Parallel Mediation Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Hierarchical Multiple Regression Results

| Dependent Variables | Predictor | Step 1 | Step 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | β | b | SE | β | ||

| Overall negative emotions | Baseline | 0.66 | 0.04 | 0.62 *** | 0.61 | 0.04 | 0.58 *** |

| Perceived social exclusion | 0.25 | 0.03 | 0.27 *** | 0.21 | 0.03 | 0.22 *** | |

| RSQ | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.03 | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.08 | |

| AAQ | 0.19 | 0.04 | 0.19 *** | ||||

| ΔR* | 0.51 *** | 0.03 ** | |||||

| Anger | Baseline | 0.59 | 0.05 | 0.50 *** | 0.56 | 0.05 | 0.47 *** |

| Perceived social exclusion | 0.32 | 0.04 | 0.30 *** | 0.28 | 0.04 | 0.26 *** | |

| RSQ | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.07 | −0.05 | 0.02 | −0.12 ** | |

| AAQ | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.16 *** | ||||

| ΔR* | 0.37 *** | 0.02 *** | |||||

| Sadness | Baseline | 0.63 | 0.04 | 0.58 *** | 0.58 | 0.04 | 0.53 *** |

| Perceived social exclusion | 0.34 | 0.04 | 0.30 *** | 0.30 | 0.04 | 0.26 *** | |

| RSQ | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.03 | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.07 | |

| AAQ | 0.22 | 0.05 | 0.17 *** | ||||

| ΔR* | 0.49 *** | 0.02 *** | |||||

| Hurt feelings | Baseline | 0.61 | 0.05 | 0.52 *** | 0.55 | 0.05 | 0.47 *** |

| Perceived social exclusion | 0.35 | 0.04 | 0.31 *** | 0.29 | 0.04 | 0.26 *** | |

| RSQ | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.04 | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.10 ** | |

| AAQ | 0.28 | 0.05 | 0.22 *** | ||||

| ΔR* | 0.43 *** | 0.04 *** | |||||

| Other negative emotions | Baseline | 0.72 | 0.04 | 0.69 *** | 0.70 | 0.04 | 0.67 *** |

| Perceived social exclusion | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.09 * | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.06 | |

| RSQ | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.001 | 0.13 | 0.001 | |

| AAQ | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.14 *** | ||||

| ΔR* | 0.51 *** | 0.02 *** | |||||

| Overall positive emotions | Baseline | 0.70 | 0.04 | 0.64 *** | 0.69 | 0.04 | 0.63 *** |

| Perceived social exclusion | −0.20 | 0.04 | −0.20 *** | −0.17 | 0.04 | −0.17 *** | |

| RSQ | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.07 | |

| AAQ | −0.09 | 0.05 | −0.08 | ||||

| ΔR* | 0.43 *** | 0.01 | |||||

Appendix B. Component Words the Emotion Scale

References

- MacDonald, G.; Leary, M.R. Why does social exclusion hurt? The relationship between social and physical pain. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 131, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shi, Y.; Xu, F.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, C. Empathetic social pain: Evidence from neuroimaging. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 23, 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.-Z.; Xia, B.-L. The Psychologicsal View on Social Exclusion. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 16, 981–986. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, K.D. Ostracism. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 425–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, D.; Wesselmann, E.D.; Williams, K.D. Hurt people hurt people: Ostracism and aggression. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2018, 19, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leary, M.R. Emotional responses to interpersonal rejection. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2022, 17, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppes, G.; Gross, J.J. Is timing everything? Temporal considerations in emotion regulation. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 15, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guiping, Z.; Shan, L. The Impact Mechanism of Social Exclusion on the Aggressive Behaviors of University Students: The Internal Mechnism of Anxiety and Narcissistic Personality. Educ. Res. 2020, 3, 95–100. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagisawa, K.; Masui, K.; Furutani, K.; Nomura, M.; Yoshida, H.; Ura, M. Temporal distance insulates against immediate social pain: An NIRS study of social exclusion. Soc. Neurosci. 2011, 6, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Lin, Y.; Xia, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, D.; Elliott, R. Critical role of the right VLPFC in emotional regulation of social exclusion: A tDCS study. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2018, 13, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chambers, R.; Gullone, E.; Allen, N.B. Mindful emotion regulation: An integrative review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 29, 560–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeWall, C.N.; Twenge, J.M.; Gitter, S.A.; Baumeister, R.F. It’s the thought that counts: The role of hostile cognition in shaping aggressive responses to social exclusion. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 96, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- DeWall, C.N.; Twenge, J.M.; Bushman, B.; Im, C.; Williams, K. A little acceptance goes a long way: Applying social impact theory to the rejection-aggression link. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2010, 1, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, R.M.; Tiedens, L.Z.; Govan, C.L. Excluded emotions: The role of anger in antisocial responses to ostracism. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 44, 896–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyckoff, J.P. Aggression and emotion: Anger, not general negative affect, predicts desire to aggress. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 101, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, F.W.; Hayes, S.C.; Barnes-Holmes, D. Psychological flexibility, ACT, and organizational behavior. J. Organ. Behav. Manag. 2006, 26, 25–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, E.K.; Creswell, J.D. Mindfulness, acceptance, and emotion regulation: Perspectives from Monitor and Acceptance Theory (MAT). Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 28, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lindsay, E.K.; Chin, B.; Greco, C.M.; Young, S.; Brown, K.W.; Wright, A.G.; Smyth, J.M.; Burkett, D.; Creswell, J.D. How mindfulness training promotes positive emotions: Dismantling acceptance skills training in two randomized controlled trials. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 115, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adair, K.C.; Fredrickson, B.L.; Castro-Schilo, L.; Kim, S.; Sidberry, S. Present with You: Does Cultivated Mindfulness Predict Greater Social Connection Through Gains in Decentering and Reductions in Negative Emotions? Mindfulness 2017, 9, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashdan, T.B.; Barrios, V.; Forsyth, J.P.; Steger, M.F. Experiential avoidance as a generalized psychological vulnerability: Comparisons with coping and emotion regulation strategies. Behav. Res. Ther. 2006, 44, 1301–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashdan, T.B.; Breen, W.E. Materialism and diminished well-being: Experiential avoidance as a mediating mechanism. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 26, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergus, T.A.; Bardeen, J.R.; Orcutt, H.K. Experiential avoidance and negative emotional experiences: The moderating role of expectancies about emotion regulation strategies. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2013, 37, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworsky, C.K.O.; Pargament, K.I.; Wong, S.; Exline, J.J. Suppressing spiritual struggles: The role of experiential avoidance in mental health. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2016, 5, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.M.; Cox, D.W.; Hubley, A.M.; Owens, R.L. Emotion regulation as a mediator of self-compassion and depressive symptoms in recurrent depression. Mindfulness 2019, 10, 1169–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cookson, C.; Luzon, O.; Newland, J.; Kingston, J. Examining the role of cognitive fusion and experiential avoidance in predicting anxiety and depression. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2020, 93, 456–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, F.W.; Hayes, S.C.; Baer, R.A.; Carpenter, K.M.; Guenole, N.; Orcutt, H.K.; Waltz, T.; Zettle, R.D. Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire–II: A revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behav. Ther. 2011, 42, 676–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roemer, L.; Lee, J.K.; Salters-Pedneault, K.; Erisman, S.M.; Orsillo, S.M.; Mennin, D.S. Mindfulness and emotion regulation difficulties in generalized anxiety disorder: Preliminary evidence for independent and overlapping contributions. Behav. Ther. 2009, 40, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shorey, R.C.; Elmquist, J.; Zucosky, H.; Febres, J.; Brasfield, H.; Stuart, G.L. Experiential Avoidance and Male Dating Violence Perpetration: An Initial Investigation. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2014, 3, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pepper, S.E. The Role of Experiential Avoidance in Trauma, Substance Abuse, and Other Experiences. Doctoral Dissertation, University of North Texas, Denton, TX, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Liang, T.; Xiang, W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Feng, Z.; Deng, G.; Xiao, J. Moderating role of overgeneral autobiographical memory in the relationship between dysfunctional attitudes and state anxiety. Stress and Brain 2022, 2, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Pfundmair, M.; DeWall, C.N.; Fries, V.; Geiger, B.; Kramer, T.; Krug, S.; Frey, D.; Aydin, N. Sugar or spice: Using I3 metatheory to understand how and why glucose reduces rejection-related aggression. Aggress. Behav. 2015, 41, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leary, M.R.; Kowalski, R.M.; Smith, L.; Phillips, S. Teasing, rejection, and violence: Case studies of the school shootings. Aggress. Behav. 2003, 29, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maner, J.K.; DeWall, C.N.; Baumeister, R.F.; Schaller, M. Does social exclusion motivate interpersonal reconnection? Resolving the ”porcupine problem”. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakiei, A.; Khazaie, H.; Rostampour, M.; Lemola, S.; Esmaeili, M.; Dursteler, K.; Bruhl, A.B.; Sadeghi-Bahmani, D.; Brand, S. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) Improves Sleep Quality, Experiential Avoidance, and Emotion Regulation in Individuals with Insomnia-Results from a Randomized Interventional Study. Life 2021, 11, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrott, W.G. Implications of dysfunctional emotions for understanding how emotions function. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2001, 5, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, A.H.; Perry, M. The aggression questionnaire. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 63, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, K.E.; Winkel, R.E.; Leary, M.R. Reactions to acceptance and rejection: Effects of level and sequence of relational evaluation. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 40, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, M.E.; Root, L.M.; Cohen, A.D. Writing about the benefits of an interpersonal transgression facilitates forgiveness. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 74, 887–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xiong, H.-X.; Zhang, J.; Ye, B.-J.; Zheng, X.; Sun, P.-Z. Common method variance effects and the models of statistical approaches for controlling it. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 20, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Østergaard, T.; Lundgren, T.; Zettle, R.D.; Landrø, N.I.; Haaland, V.Ø. Psychological flexibility in depression relapse prevention: Processes of change and positive mental health in group-based ACT for residual symptoms. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fledderus, M.; Bohlmeijer, E.T.; Fox, J.-P.; Schreurs, K.M.; Spinhoven, P. The role of psychological flexibility in a self-help acceptance and commitment therapy intervention for psychological distress in a randomized controlled trial. Behav. Res. Ther. 2013, 51, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luoma, J.B.; Hayes, S.C.; Walser, R.D. Learning ACT: An Acceptance & Commitment Therapy Skills-Training Manual for Therapists; New Harbinger Publications: Oakland, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth, J.P.; Eifert, G.H. The Mindfulness and Acceptance Workbook for Anxiety: A Guide to Breaking Free from Anxiety, Phobias, and Worry Using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy; New Harbinger Publications: Oakland, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shallcross, A.J.; Troy, A.S.; Boland, M.; Mauss, I.B. Let it be: Accepting negative emotional experiences predicts decreased negative affect and depressive symptoms. Behav. Res. Ther. 2010, 48, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shea, S.E.; Coyne, L.W. Reliance on experiential avoidance in the context of relational aggression: Links to internalizing and externalizing problems and dysphoric mood among urban, minority adolescent girls. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2017, 6, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.L.; Updegraff, J.A. Mindfulness and its relationship to emotional regulation. Emotion 2012, 12, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tull, M.T.; Roemer, L. Emotion regulation difficulties associated with the experience of uncued panic attacks: Evidence of experiential avoidance, emotional nonacceptance, and decreased emotional clarity. Behav. Ther. 2007, 38, 378–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldao, A.; Nolen-Hoeksema, S.; Schweizer, S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grezellschak, S.; Lincoln, T.M.; Westermann, S. Cognitive emotion regulation in patients with schizophrenia: Evidence for effective reappraisal and distraction. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 229, 434–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Harmon-Jones, E. Anger is an approach-related affect: Evidence and implications. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 135, 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eifert, G.H.; Forsyth, J.P. The application of acceptance and commitment therapy to problem anger. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2011, 18, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-H. Affective Style and Aggressive Behavior in Adolescents. Doctoral Dissertation, Capital Normal University, Beijing, China, 2005. Available online: https://kns-cnki-net-443.vpn.sicnu.edu.cn/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CDFD9908&filename=2005074062.nh (accessed on 15 September 2015). (In Chinese).

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 AAQ | 4.13 | 1.27 | 1 | |||||||

| 2 Overall negative emotions | 2.76 | 1.30 | 0.41 *** | 1 | ||||||

| 3 Anger | 2.71 | 1.46 | 0.32 *** | 0.87 *** | 1 | |||||

| 4 Sadness | 3.18 | 1.60 | 0.43 *** | 0.90 *** | 0.68 *** | 1 | ||||

| 5 Hurt feelings | 3.03 | 1.57 | 0.42 *** | 0.93 *** | 0.73 *** | 0.91 *** | 1 | |||

| 6 Other negative emotions | 2.36 | 1.29 | 0.33 *** | 0.88 *** | 0.68 *** | 0.68 *** | 0.73 *** | 1 | ||

| 7 Positive emotions | 2.79 | 1.40 | −0.23 *** | 0.08 | 0.10 ** | −0.08 | −0.06 | 0.28 ** | 1 | |

| 8 Aggressive tendency | 2.78 | 0.98 | 0.33 *** | 0.36 *** | 0.48 *** | 0.25 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.23 *** | 0.02 | 1 |

| Dependent Variables | Predictor | Step 1 | Step 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | β | b | SE | β | ||

| Aggressive tendency | Perceived social exclusion | 0.22 | 0.03 | 0.31 *** | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.27 *** |

| RSQ | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.11 * | −0.04 | 0.01 | −0.15 ** | |

| AQ | 0.53 | 0.07 | 0.36 *** | 0.44 | 0.07 | 0.30 *** | |

| AAQ | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.17 ** | ||||

| ΔR2 | 0.26 *** | 0.02 *** | |||||

| Paths | Indirect Effects | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | Relative Mediation Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect: AAQ→AT | 0.205 | 0.039 | 0.128 | 0.281 | - |

| Direct effect: AAQ→AT | 0.184 | 0.036 | 0.113 | 0.255 | - |

| Total indirect effects | |||||

| Ind1: AAQ→Anger→AT | 0.064 | 0.027 | 0.012 | 0.118 | 31.22% |

| Ind2: AAQ→Sadness→AT | −0.029 | 0.015 | −0.063 | −0.005 | 14.15% |

| Ind3: AAQ→Hurt feelings→AT | −0.006 | 0.015 | −0.039 | 0.023 | - |

| Ind4: AAQ→Other negative emotions→AT | −0.009 | 0.010 | −0.031 | 0.011 | - |

| Compare1:Ind1-Ind2 | 0.093 | 0.034 | 0.029 | 0.164 | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, C.; Mao, J.; Yang, Q.; Yuan, J.; Yang, J. Trait Acceptance Buffers Aggressive Tendency by the Regulation of Anger during Social Exclusion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214666

He C, Mao J, Yang Q, Yuan J, Yang J. Trait Acceptance Buffers Aggressive Tendency by the Regulation of Anger during Social Exclusion. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(22):14666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214666

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Conglian, Jixuan Mao, Qian Yang, Jiajin Yuan, and Jiemin Yang. 2022. "Trait Acceptance Buffers Aggressive Tendency by the Regulation of Anger during Social Exclusion" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 22: 14666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214666

APA StyleHe, C., Mao, J., Yang, Q., Yuan, J., & Yang, J. (2022). Trait Acceptance Buffers Aggressive Tendency by the Regulation of Anger during Social Exclusion. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 14666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214666