Residents’ Behavioral Intention of Environmental Governance and Its Influencing Factors: Based on a Multidimensional Willingness Measure Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

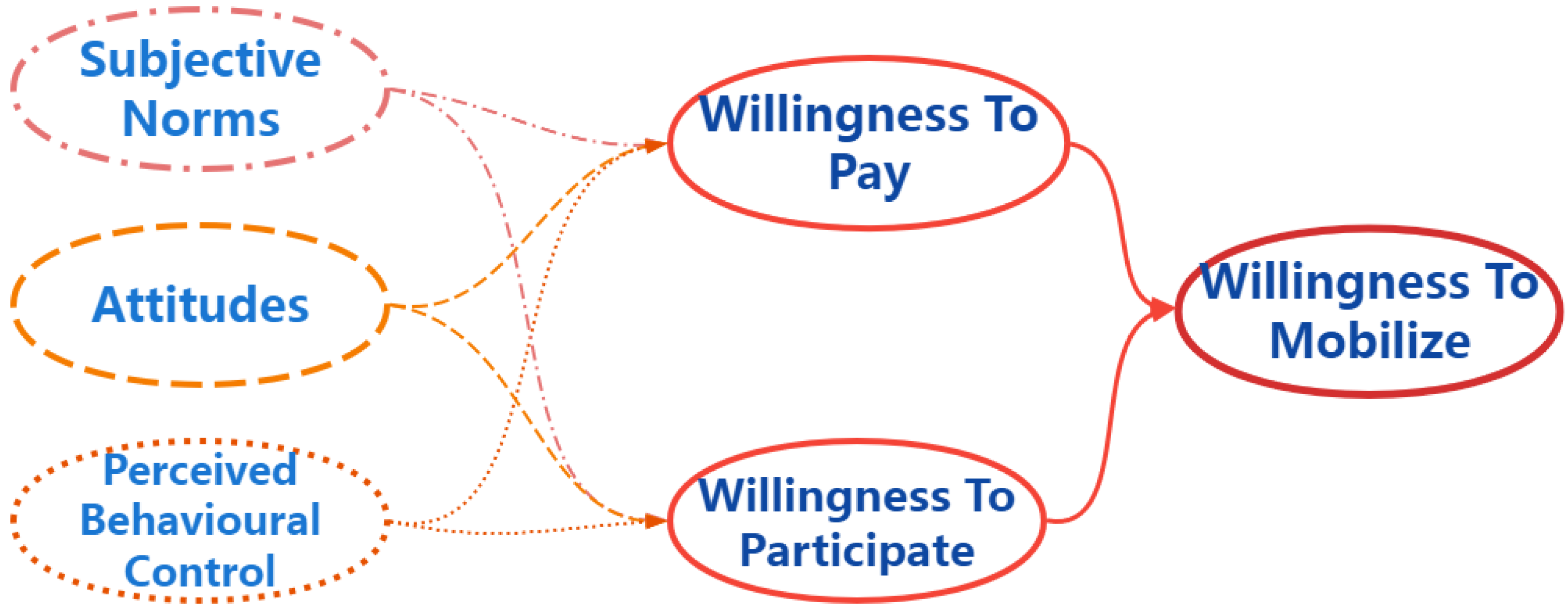

2. Model Construction

2.1. Theory of Planned Behavior

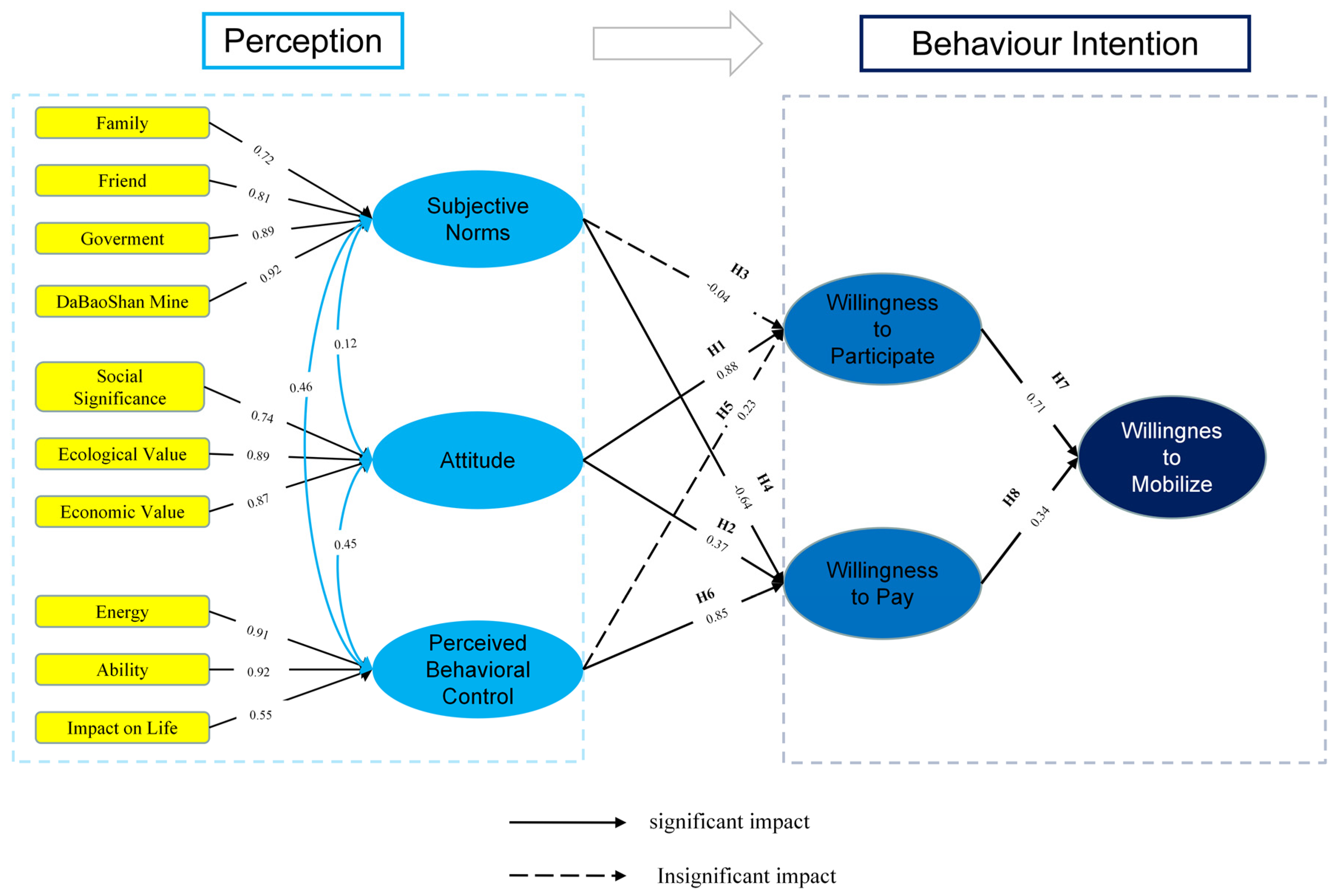

2.2. Model Framework and Research Assumptions

3. Methods

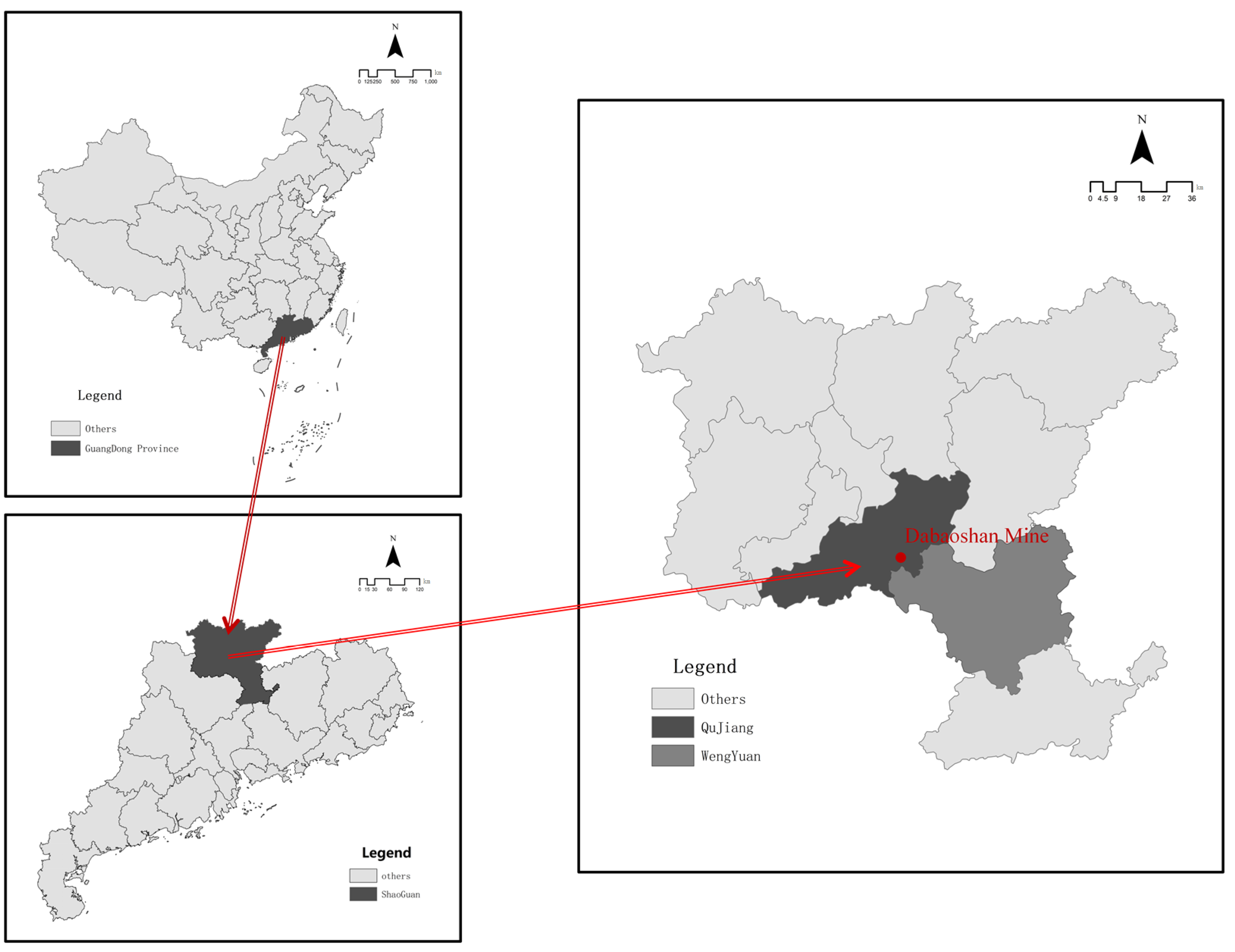

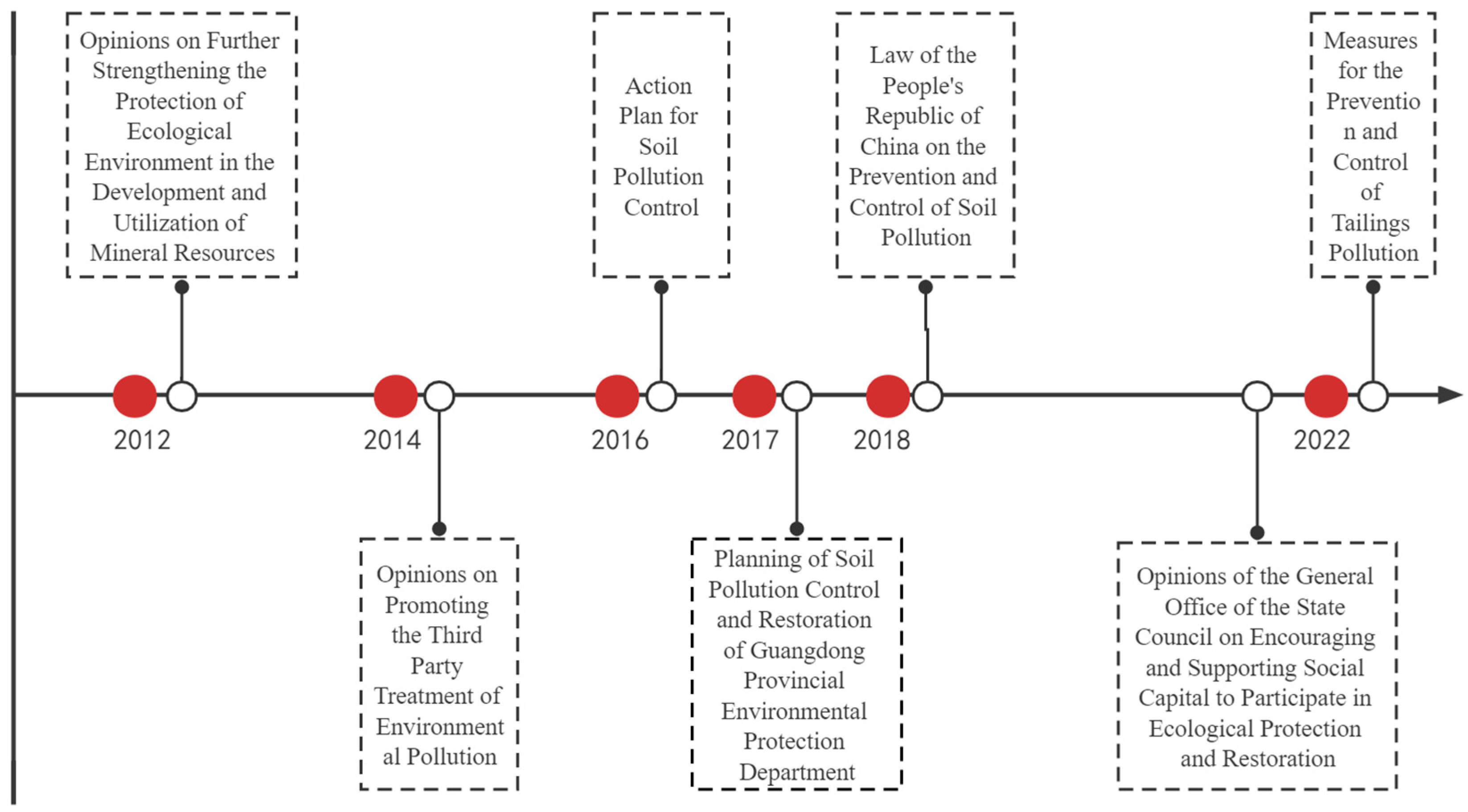

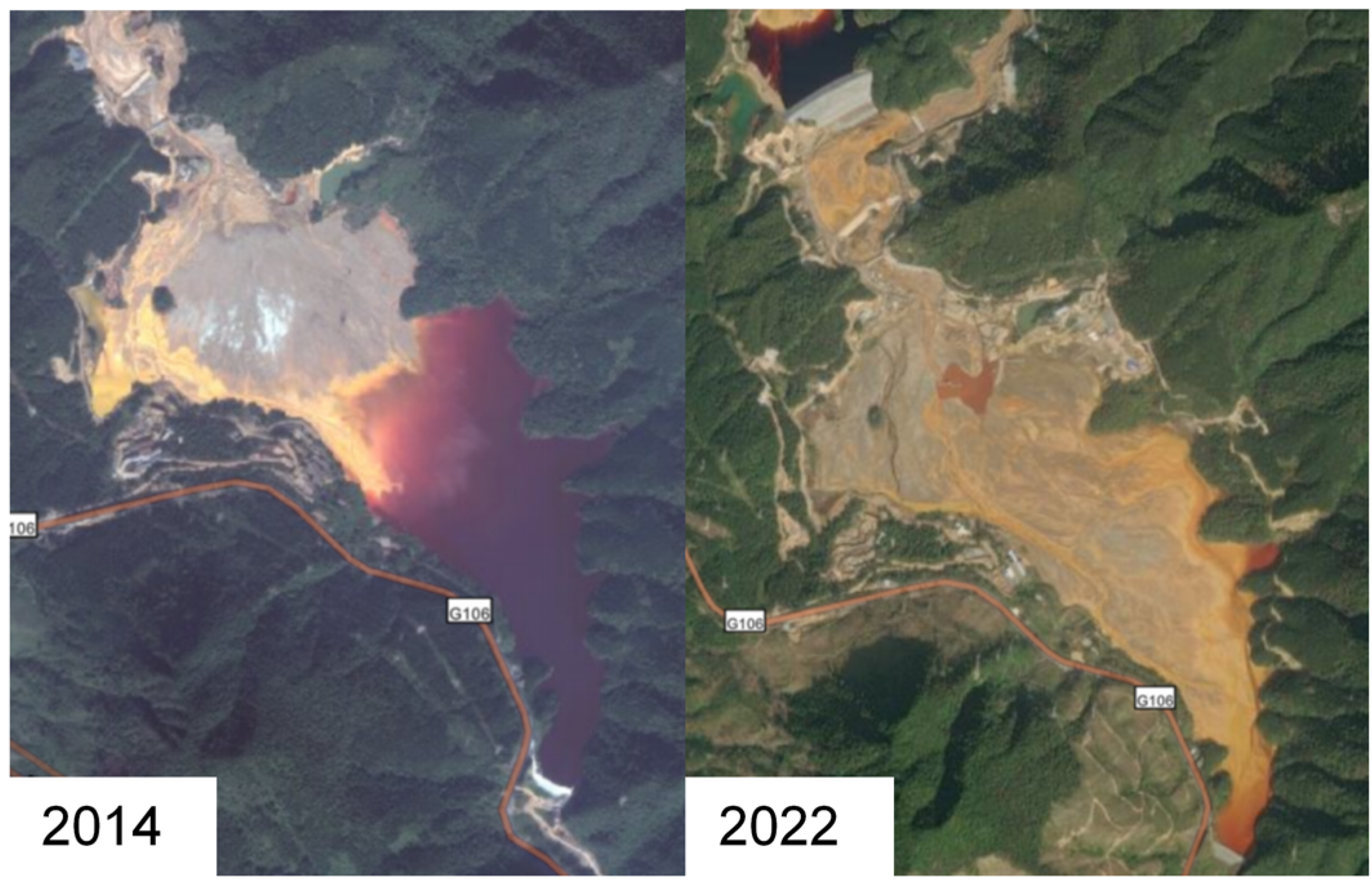

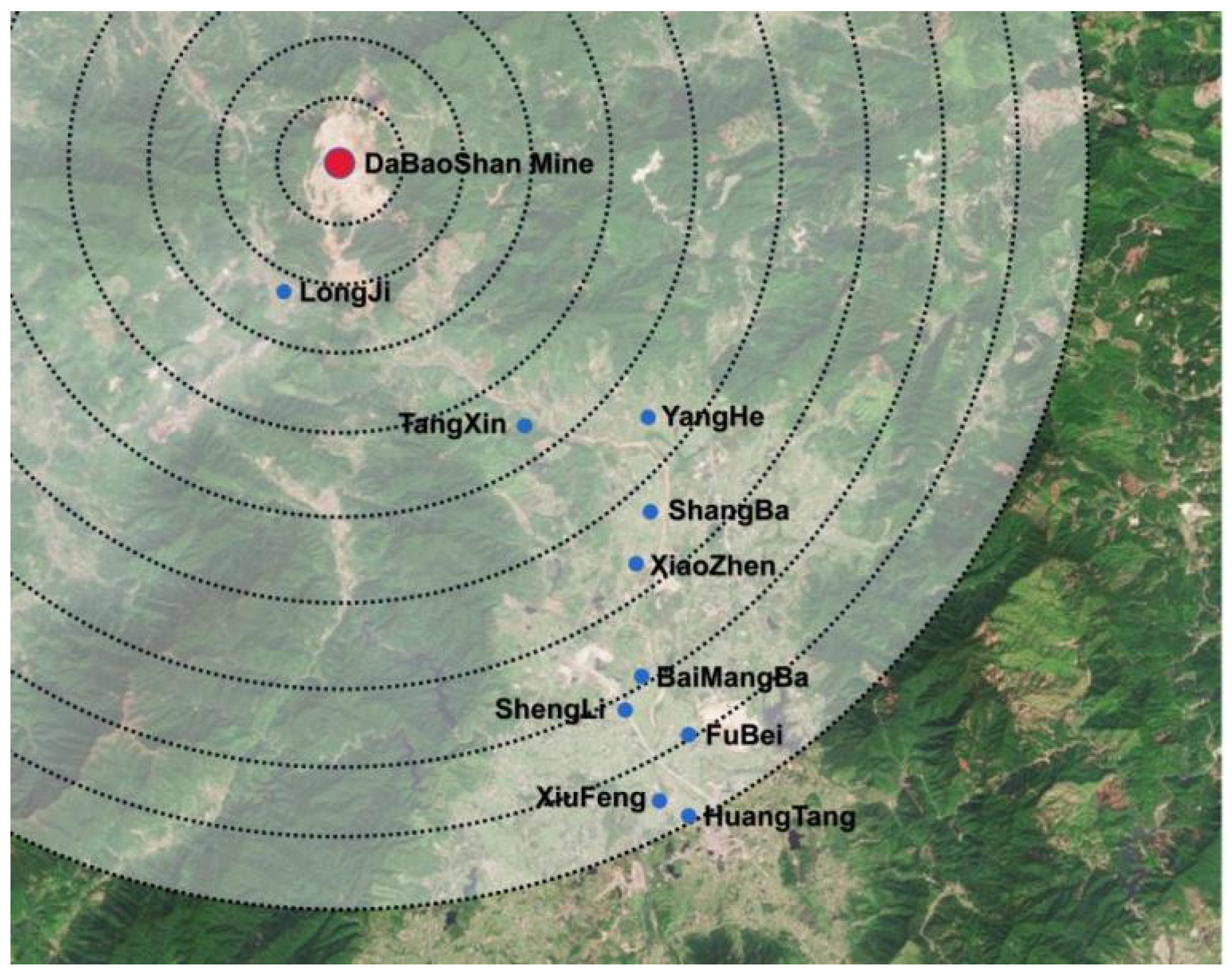

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Variable Description

3.4. Descriptive Analysis

3.5. Measurement Model

3.6. Structural Model

4. Results and Policy Implications

4.1. Results

- (1)

- Attitudes have a positive impact on residents’ willingness to participate and willingness to pay.

- (2)

- Subjective norms do not affect residents’ willingness to participate, but significantly affect their willingness to pay and are negatively correlated.

- (3)

- Perceived behavioral control has a significant influence on residents’ willingness to pay.

- (4)

- Willingness to participate and willingness to pay can significantly affect willingness to mobilize, and the impact factor of willingness to participate is higher.

4.2. Policy Implications

- (1)

- Recognition: strengthen the social, economic, and ecological value perception of land pollution abatement.

- (2)

- Empowerment: cultivate residents’ subjective consciousness.

- (3)

- Cooperation: build a neighborhood communication platform.

- (4)

- Improvement: enhance the ability to participate.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dong, L.; Tong, X.; Li, X.; Zhou, J.; Wang, S.; Liu, B. Some developments and new insights of environmental problems and deep mining strategy for cleaner production in mines. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 1562–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Guo, T.; Jiao, W. Destruction processes of mining on water environment in the mining area combining isotopic and hydrochemical tracer. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 237, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, B.; Kurisu, K.; Hanaki, K.; Che, Y. Influential factors of public intention to improve the air quality in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 209, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S.; Vella, S.; Challies, E.; de Vente, J.; Frewer, L.; Hohenwallner-Ries, D.; Huber, T.; Neumann, R.K.; Oughton, E.A.; del Ceno, J.S.; et al. A theory of participation: What makes stakeholder and public engagement in environmental management work? Restor. Ecol. 2018, 26, S7–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, K.; Nabatchi, T.; Balogh, S. An Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance. J. Publ. Adm. Res. Theor. 2011, 22, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice. J. Publ. Adm. Res. Theor. 2007, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withanachchi, S.; Kunchulia, I.; Ghambashidze, G.; Al Sidawi, R.; Urushadze, T.; Ploeger, A. Farmers’ Perception of Water Quality and Risks in the Mashavera River Basin, Georgia: Analyzing the Vulnerability of the Social-Ecological System through Community Perceptions. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.D.L.C.; Palmer, J.D.S.M. Is public awareness and perceived threat of climate change associated with. Clim. Chang. 2018, 149, 159–171. [Google Scholar]

- Pu, S.; Shao, Z.; Fang, M.; Yang, L.; Liu, R.; Bi, J.; Ma, Z. Spatial distribution of the public’s risk perception for air pollution: A nationwide study in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 655, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xia, M.; Guo, X.; Shi, Y.; Guan, R.; Liu, Q.; Cai, Y.; Lu, H. Spatial characteristics and influencing factors of risk perception of haze in China: The case study of publishing online comments about haze news on Sina. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 785, 147236. [Google Scholar]

- Reames, T.G.; Bravo, M.A. People, place and pollution: Investigating relationships between air quality perceptions, health concerns, exposure, and individual- and area-level characteristics. Environ. Int. 2019, 122, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Tilt, B. Perceptions of Quality of Life and Pollution among China’s Urban Middle Class: The Case of Smog in Tangshan. China Q. 2018, 234, 340–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.; Chang, H. Cultural dimensions of risk perceptions: A case study on cross-strait driftage pollution in a coastal area of Taiwan. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 206, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurice, L.; López, F.; Becerra, S.; Jamhoury, H.; Le Menach, K.; Dévier, M.-H.; Budzinski, H.; Prunier, J.; Juteau-Martineau, G.; Ochoa-Herrera, V.; et al. Drinking water quality in areas impacted by oil activities in Ecuador: Associated health risks and social perception of human exposure. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 690, 1203–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffle, R.W.; Traugott, M.W.; Stone, J.V.; Mcintyre, P.D.; Jensen, F.V.; Davidson, C.C. Risk Perception Mapping: Using Ethnography to Define the Locally Affected Population for a Low-Level Radioactive Waste Storage Facility in Michigan. Am. Anthropol. 1991, 93, 611–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Wang, A.; Zhang, A.T. Pollution exposure and willingness to pay for clean air in urban China. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 261, 110174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicatiello, L.; Ercolano, S.; Gaeta, G.L.; Pinto, M. Willingness to pay for environmental protection and the importance of pollutant industries in the regional economy. Evidence from Italy. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 177, 106774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, A.; Bondori, A.; Allahyari, M.S.; Damalas, C.A. Modeling farmers’ intention to use pesticides: An expanded version of the theory of planned behavior. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 248, 109291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Wang, S.; Zhao, D. Exploring urban resident’s vehicular PM2.5 reduction behavior intention: An application of the extended theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 147, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghoubi Farani, A.; Mohammadi, Y.; Ghahremani, F. Modeling farmers’ responsible environmental attitude and behaviour: A case from Iran. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R 2019, 26, 28146–28161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, S.; Batista-Foguet, J.M.; van Wunnik, L. Exploring the public’s willingness to reduce air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions from private road transport in Catalonia. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 646, 850–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Ding, Z.; Li, X.; Sun, J.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, R.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Sun, W. How cultural values and anticipated guilt matter in Chinese residents’ intention of low carbon consuming behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 246, 119069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, M.; Chang, C.; Shaw, D. Individuals’ intentions to mitigate air pollution: Vehicles, household appliances, and religious practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 227, 566–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.; López-Mosquera, N.; Lera-López, F.; Faulin, J. An Extended Planned Behavior Model to Explain the Willingness to Pay to Reduce Noise Pollution in Road Transportation. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 177, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Hipel, K.W.; Hanson, M.L.; Cai, X.; Liu, Y. An analysis of influencing factors on municipal solid waste source-separated collection behavior in Guilin, China by Using the Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 37, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Tian, Z.; Fan, M. Do the rich have stronger willingness to pay for environmental protection? New evidence from a survey in China. World Dev. 2018, 105, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Yuan, X.; Xu, M. The public perceptions and willingness to pay: From the perspective of the smog crisis in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1635–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atinkut, H.B.; Yan, T.; Arega, Y.; Raza, M.H. Farmers’ willingness-to-pay for eco-friendly agricultural waste management in Ethiopia: A contingent valuation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 261, 121211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agag, G.; El-Masry, A.A. Understanding consumer intention to participate in online travel community and effects on consumer intention to purchase travel online and WOM: An integration of innovation diffusion theory and TAM with trust. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 60, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Dong, X.; Yin, J. Antecedents of urban residents’ separate collection intentions for household solid waste and their willingness to pay: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 173, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreen, N.; Purbey, S.; Sadarangani, P. Impact of culture, behavior and gender on green purchase intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Law, R.; Schuckert, M. Mediating effects of attitude, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control for mobile payment-based hotel reservations. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 84, 102331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuriev, A.; Dahmen, M.; Paillé, P.; Boiral, O.; Guillaumie, L. Pro-environmental behaviors through the lens of the theory of planned behavior: A scoping review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 155, 104660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufique, K.M.R.; Vaithianathan, S. A fresh look at understanding Green consumer behavior among young urban Indian consumers through the lens of Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 183, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataei, P.; Gholamrezai, S.; Movahedi, R.; Aliabadi, V. An analysis of farmers’ intention to use green pesticides: The application of the extended theory of planned behavior and health belief model. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 81, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, A.; Emami, N.; Damalas, C.A. Farmers’ behavior towards safe pesticide handling: An analysis with the theory of planned behavior. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 751, 141709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Yu, P.; Hu, H. The theory of planned behavior as a model for understanding tourists’ responsible environmental behaviors: The moderating role of environmental interpretations. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 194, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 176–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Determinants of Consumers’ Green Purchase Behavior in a Developing Nation: Applying and Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 134, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Fan, J.; Zhao, D.; Yang, S.; Fu, Y. Predicting consumers’ intention to adopt hybrid electric vehicles: Using an extended version of the theory of planned behavior model. Transportation 2016, 43, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Ye, H.; Li, X.; Yi, X.; Wen, Z.; Wang, H.; Lu, Z.; Dang, Z. Spatial distribution characteristics of the microbial community and multi-phase distribution of toxic metals in the geochemical gradients caused by acid mine drainage, South China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 774, 145660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Z.; Yao, Q.; Chen, K.; Zheng, X.; Fu, H.; Liao, Z.; Lu, G. The cause of pollution and the application progress of source control technology in Dabaoshan mining area in north Guangdong Province. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2021, 40, 1377–1386. [Google Scholar]

- Swami, V.; Chamorro-Premuzic, T.; Snelgar, R.; Furnham, A. Personality, individual differences, and demographic antecedents of self-reported household waste management behaviours. J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Nam, M.; Cha, S. University students’ behavioral intention to use mobile learning: Evaluating the technology acceptance model. Brit. J. Educ. Technol. 2012, 43, 592–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Yang, Y. RMSEA, CFI, and TLI in structural equation modeling with ordered categorical data: The story they tell depends on the estimation methods. Behav. Res. Methods 2019, 51, 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makransky, G.; Lilleholt, L. A structural equation modeling investigation of the emotional value of immersive virtual reality in education. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2018, 66, 1141–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Khachatryan, H.; Zhu, H. Poyang lake wetlands restoration in China: An analysis of farmers’ perceptions and willingness to participate. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 284, 125001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Pow, C.P.; Neo, H. Environmental governance with ‘Chinese characteristics’ and citizenship participation in Nanjing. Habitat Int. 2019, 84, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, R.J.F. Reconceptualising the ‘behavioural approach’ in agricultural studies: A socio-psychological perspective. J. Rural Stud. 2004, 20, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name of Organization | Project Name |

|---|---|

| Grass and Wood Demonstration Base | |

| South China University of Technology South China Agricultural University Wuhan Zhongdi Jindun Environmental Technology Co., Ltd. | Research and development of geochemical engineering remediation technology for heavy metal pollution in farmland |

| Environmental Protection Research and Monitoring Institute, Ministry of Agriculture | Intercropping of maize with low accumulation of heavy metals and hyperaccumulation plants for remediation technology demonstration |

| Shaoguan Environmental Protection Bureau Shaoguan Agriculture Bureau Shaoguan Science and Technology Bureau Guangdong Province Environmental Science Research Institute | Farmland soil remediation verification and evaluation platform in northern Guangdong |

| Zhejiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences | Enhanced repair techniques of hybrid rice intercropping system with super/high enrichment plants under different rice-ripening systems |

| Institute of Botany Chinese Academy of Sciences | Study on selection and evaluation of maize varieties with low heavy metal accumulation |

| Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, CAS | Intercropping-enhanced remediation techniques of rice/maize with low heavy metal accumulation and hyperenrichment plants under different conditioning modes |

| Guangdong Academy of Environmental Sciences | Tielong Forest Farm farmland soil planting structure adjustment test base |

| Guangdong Academy of Environmental Sciences | Remediation demonstration project of heavy metal contaminated soil in Tielong Forest Farm, Wengyuan County, Shaoguan City |

| Time | January 2016 | November 2016 | May 2020 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling Location | LiangQiao | ShangBa | LiangQiao | ShangBa | LiangQiao | ShangBa |

| pH | 3.86 | 4.78 | 8.7 | 7.9 | 6.12 | 6.68 |

| Fe (mg∙L−1) | 25 | 12 | 4 | — | — | — |

| Mn (mg∙L−1) | 15 | 9 | — | — | — | — |

| Zn (mg∙L−1) | 6 | 5 | — | — | — | — |

| Cu (mg∙L−1) | 2 | 1 | — | — | — | — |

| Cd (mg∙L−1) | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Pb (mg∙L−1) | 0.08 | — | — | — | — | — |

| SO42− (mg∙L−1) | 1030 | 798 | 382 | 130 | 299 | 107 |

| Place | N | Distance | Mean (Willingness to Participate) | Mean (Willingness to Pay) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LongJi | 48 | 2 | 4.81 | 3.54 |

| Tangxin | 40 | 4 | 4.56 | 4.03 |

| Yanghe | 100 | 5 | 4.37 | 4.23 |

| Shangba | 48 | 6 | 3.98 | 3.71 |

| Xiaozhen | 42 | 6 | 4.12 | 3.95 |

| BaiMangBa | 52 | 7 | 3.56 | 3.00 |

| Shengli | 58 | 8 | 3.93 | 2.48 |

| Fubei | 50 | 8 | 3.00 | 2.92 |

| Xiufeng | 50 | 9 | 3.96 | 3.18 |

| Huangtang | 52 | 9 | 4.02 | 3.13 |

| Construct | Indicators | Response Scale (1–5) | References Used | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitudes | ATT1 | Do you think it is meaningful for residents to participate in the land pollution abatement of the Dabaoshan mining area? | Meaningless–Very meaningful | [24] |

| ATT2 | Participating in the land pollution abatement of the Dabaoshan mining area can improve crop quality | Strongly disagree–Strongly agree | ||

| ATT3 | Participating in the land pollution abatement of the Dabaoshan mining area can improve the surrounding environment | Strongly disagree–Strongly agree | ||

| Subjective Norms | SN1 | Will your family’s attitude affect your enthusiasm to participate in the land pollution abatement of the Dabaoshan mining area? | No effect–Very influential | |

| SN2 | Will the attitude of your neighbors and friends affect your enthusiasm to participate in the land pollution abatement of the Dabaoshan mining area? | No effect–Very influential | ||

| SN3 | Will the attitude of the local government affect your enthusiasm to participate in the land pollution abatement of the Dabaoshan mining area? | No effect–Very influential | ||

| SN4 | Will the attitude of the Dabaoshan Mining Company affect your enthusiasm to participate in the land pollution abatement of the Dabaoshan mining area? | No effect–Very influential | ||

| Perceived Behavioral Control | PBC1 | Do you have the energy to participate in the land pollution abatement of the Dabaoshan mining area? | No energy–very energetic | |

| PBC2 | Are you capable of participating in the land pollution abatement of the Dabaoshan mining area? | Incapable–very capable | ||

| PBC3 | Participation in the Dabaoshan Mine land pollution abatement will take up your daily rest time, thereby reducing your income. (Do you agree with this statement?) | Disagree–agree strongly | ||

| Willingness to Participate | PW1 | In order to protect the ecological environment, are you willing to participate in the land pollution abatement of the Dabaoshan mining area? | Very unwilling–Very willing | |

| Willingness to pay | WTP1 | In order to protect the ecological environment, are you willing to pay a fee for the land pollution abatement of the Dabaoshan mining area? | Very unwilling–Very willing | [21] |

| Willingness to mobilize | MW1 | In order to protect the ecological environment, are you willing to mobilize the surrounding people to participate in the land pollution abatement of the Dabaoshan mining area? | Very unwilling–Very willing | |

| Feature | Number of Samples | Proportion (%) | Feature | Number of Samples | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Land contracted by the family (m2) | ||||

| Male | 323 | 59.81 | ≤2667 | 291 | 53.89 |

| Female | 217 | 40.19 | 2667–4000 | 116 | 2148 |

| Age | 4000–5333 | 80 | 14.81 | ||

| ≤40 | 220 | 40.74 | >5333 | 53 | 9.81 |

| 40–50 | 187 | 34.63 | Annual income | ||

| 50–60 | 99 | 18.33 | ≤30,000 | 82 | 15.19 |

| 60–70 | 30 | 5.56 | 30,000–60,000 | 196 | 36.30 |

| >70 | 4 | 0.74 | 60,000–90,000 | 111 | 20.56 |

| Education | 90,000–120,000 | 119 | 22.04 | ||

| Illiterate or semi-literate | 10 | 1.85 | More than 120,000 | 32 | 5.93 |

| Elementary school | 132 | 24.44 | Occupation | ||

| Junior high school | 256 | 47.41 | Farmer | 271 | 40.19 |

| Senior high school | 107 | 19.81 | Worker | 166 | 30.74 |

| Junior college and above | 35 | 6.48 | Businessperson | 52 | 9.63 |

| Used to be a village cadre | Teacher | 4 | 0.74 | ||

| Yes | 31 | 5.74 | Governmental personnel | 4 | 0.74 |

| No | 509 | 94.26 | Student | 7 | 1.30 |

| Others | 36 | 6.67 |

| Constructs | Indicator | Factor Loadings | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | Composite Reliability (CR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | ATT1 | 0.74 | 0.711 | 0.880 |

| ATT2 | 0.90 | |||

| ATT3 | 0.88 | |||

| Subjective norms | SN1 | 0.77 | 0.721 | 0.911 |

| SN2 | 0.85 | |||

| SN3 | 0.88 | |||

| SN4 | 0.89 | |||

| Perceived behavioral control | PBC1 | 0.89 | 0.664 | 0.851 |

| PBC2 | 0.93 | |||

| PBC3 | 0.58 |

| Latent Variable | ATT | SN | PBC |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATT | 0.843 | ||

| SN | 0.077 | 0.849 | |

| PBC | 0.467 *** | 0.490 *** | 0.815 |

| Indicator | Criteria | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute fit measures | PCMIN/DF | <3.00 | 2.837 | |

| RMESA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation | <0.08 | 0.058 | |

| AGFI | Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index | >0.80 | 0.929 | |

| GFI | Goodness of Fit Index | >0.80 | 0.963 | |

| SRMR | Standard Root Mean Square Residual | <0.08 | 0.034 | |

| Incremental fit measures | NFI | Normed Fit Index | >0.90 | 0.971 |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index | >0.90 | 0.981 | |

| IFI | Incremental fit index | >0.90 | 0.981 | |

| TLI | Tucker Lewis Index | >0.90 | 0.969 | |

| Parsimonious fit measures | PGFI | Parsimonious Goodness of Fit Index | >0.50 | 0.508 |

| PNFI | Parsimonious Normed Fit Index | >0.50 | 0.598 | |

| PCFI | Parsimonious Comparative Fit Index | >0.50 | 0.604 |

| Endogenous Variables | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Willingness to Participate | Willingness to Pay | Motivation Intention | |

| Direct effects | |||

| Attitude | 0.883 *** | 0.372 *** | |

| Subjective norms | −0.036 | −0.639 *** | |

| Perceived behavioral control | 0.229 *** | 0.848 *** | |

| Willingness to participate | 0.340 *** | ||

| Willingness to pay | 0.714 *** | ||

| Indirect effects | |||

| Attitude | 0.757 *** | ||

| Subjective norms | −0.242 *** | ||

| Perceived Behavioral control | 0.452 *** | ||

| Willingness to participate | |||

| Willingness to pay | |||

| Total effects | |||

| Attitude | 0.883 *** | 0.372 *** | 0.757 *** |

| Subjective norms | −0.036 *** | 0.639 *** | −0.242 *** |

| Perceived behavioral control | 0.229 *** | 0.848 *** | 0.452 *** |

| Willingness to participate | 0.741 *** | ||

| Willingness to pay | 0.340 *** | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, S.; Xia, Y.; Xiao, R.; Jiang, H. Residents’ Behavioral Intention of Environmental Governance and Its Influencing Factors: Based on a Multidimensional Willingness Measure Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14734. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214734

Li S, Xia Y, Xiao R, Jiang H. Residents’ Behavioral Intention of Environmental Governance and Its Influencing Factors: Based on a Multidimensional Willingness Measure Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(22):14734. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214734

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Shijie, Yan Xia, Rongbo Xiao, and Haiyan Jiang. 2022. "Residents’ Behavioral Intention of Environmental Governance and Its Influencing Factors: Based on a Multidimensional Willingness Measure Perspective" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 22: 14734. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214734

APA StyleLi, S., Xia, Y., Xiao, R., & Jiang, H. (2022). Residents’ Behavioral Intention of Environmental Governance and Its Influencing Factors: Based on a Multidimensional Willingness Measure Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 14734. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214734