Environmental Regulation, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Disclosure and Enterprise Green Innovation: Evidence from Listed Companies in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

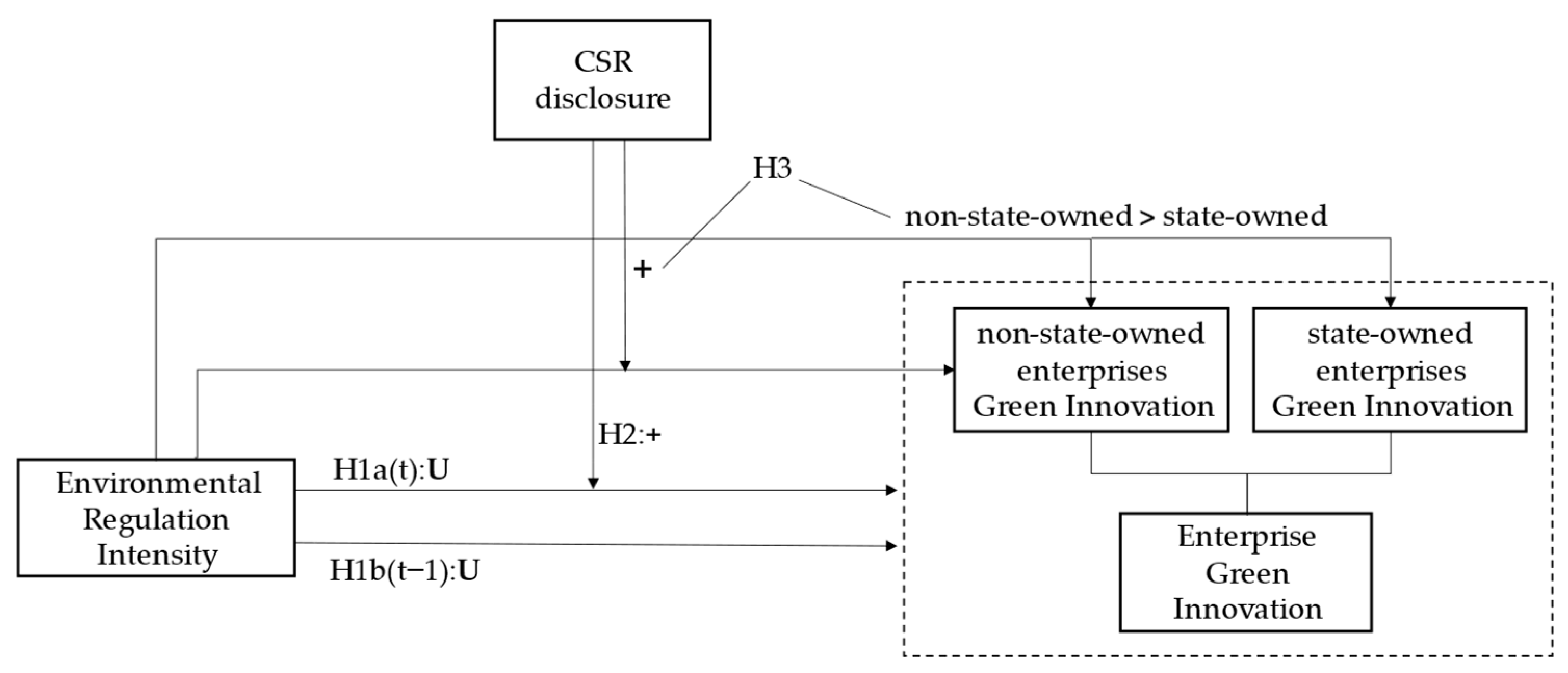

- Can environmental regulation in the current period and in the lagging period promote enterprises’ green innovation?

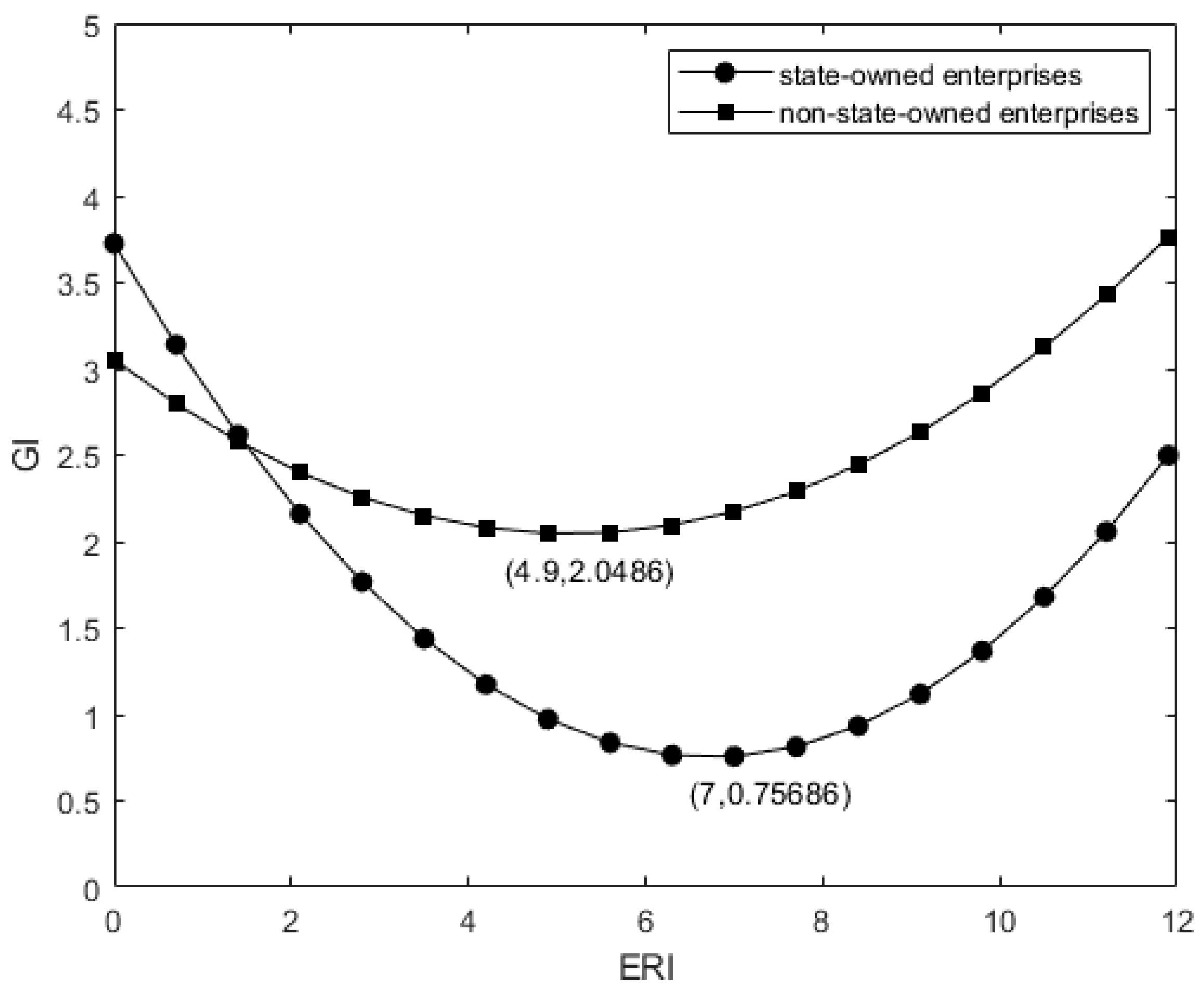

- Is the relationship between environmental regulation and green innovation different between state-owned and non-state-owned enterprises?

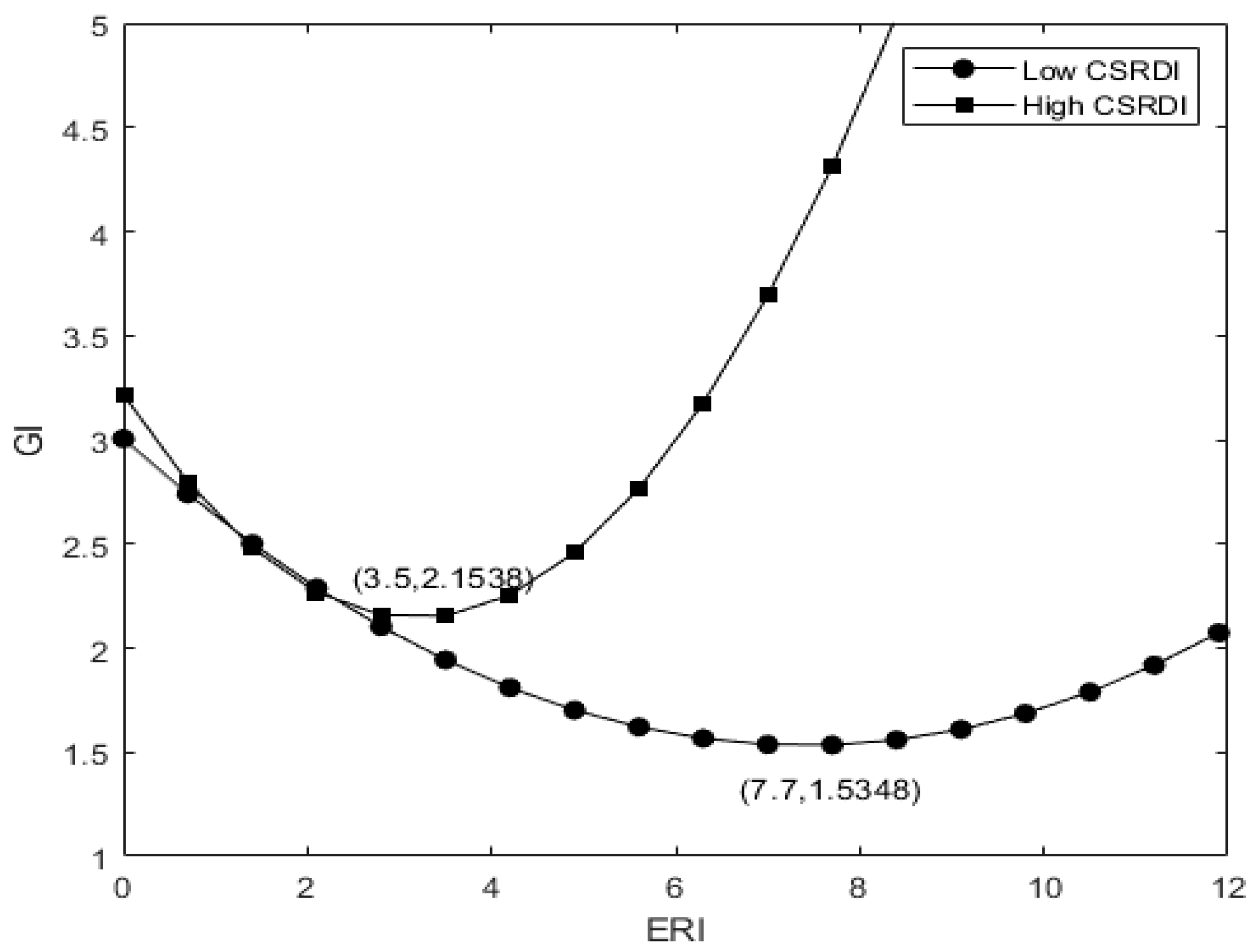

- Does CSR disclosure have a certain regulatory effect on environmental regulation and enterprise green innovation?

- Does CSR disclosure have different effects in state-owned and non-state-owned enterprises?

2. Theoretical Analysis and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Environmental Regulation and Enterprise Green Innovation

2.2. The Regulatory Effect of CSR Disclosure

2.3. Analysis of the Green Innovation Behavior of Enterprises with Heterogeneous Property Rights

3. Research Design

3.1. Sample and Data Sources

3.2. Variable Definition

3.2.1. Explained Variable-Enterprise Green Innovation (GI)

3.2.2. Explanatory Variable–Environmental Regulatory Intensity (ERI)

3.2.3. Moderator Variable-Enterprise Social Responsibility Information (CSR)

3.2.4. Control Variable

3.3. Model Design

3.4. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Test

4. Regression Analysis

5. Robustness Test

5.1. Replacement Variable Method

5.2. Endurance Test

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rapsikevicius, J.; Bruneckiene, J.; Lukauskas, M.; Mikalonis, S. The Impact of Economic Freedom on Economic and Environmental Performance: Evidence from European Countries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, M.; Zhou, P.; Iqbal, N.; Shah, S.A.A. Assessing oil supply security of South Asia. Energy 2018, 155, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Phan, T.N.; Baird, K. The comprehensiveness of environmental management systems: The influence of institutional pressures and the impact on environmental performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 160, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.R.; Chen, S.C.; Meng, T.G. Executives’ experience in public office, central environmental protection inspectors and corporate environmental performance--an empirical analysis based on firm-level data in province A. J. Public Adm. 2021, 18, 114–125,173. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Ling, H.C.; Chen, J. Economic policy uncertainty, corporate social responsibility and corporate technological innovation. Sci. Res. 2021, 39, 544–555. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, P.C.; Yang, S.W. Research on corporate socially responsible investment model:value-based judgment criteria. China Ind. Econ. 2016, 7, 109–126. [Google Scholar]

- Berrone, P.; Fosfuri, A.; Gelabert, L.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. Necessity as the mother of ‘Green’ innovations: Institutional Pressures and Environmental Innovations. Strategic Manag. J. 2013, 34, 892–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, P.R.; Medlock, K.B., III; Jankovska, O. Electricity reform and retail pricing in Texas. Energy Econ. 2019, 80, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xiao, Y. Environmental protection tax and green innovation in China: Leverage or crowding-out effect? Econ. Res. 2022, 57, 72–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, F.; Zhao, J.Y.; Zhou, H. Has environmental regulation achieved “incremental improvement” in green technology innovation? Has environmental regulation achieved “increased quantity and quality” of green technology innovation—Evidence from the environmental protection target responsibility system. China Ind. Econ. 2021, 2, 136–154. [Google Scholar]

- Ambec, S.; Cohen, M.A.; Elgie, S.; Lanoie, P. The Porter Hypothesis at 20: Can Environmental Regulation Enhance Innovation and Competitiveness? Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2013, 7, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garrone, P.; Grilli, L.; Mrkajic, B. The energy-efficient transformation of EU business enterprises: Adapting policies to contextual factors. Energy Policy 2017, 109, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jinjarak, Y.; Ahmed, R.; Nair-Desai, S.; Xin, W.; Aizenman, J. Pandemic shocks and fiscal-monetary policies in the Eurozone: COVID-19 dominance during January–June 2020. Oxf. Econ. Pap. 2021, 73, 1557–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesidou, E.; Wu, L. Stringency of environmental regulation and eco-innovation: Evidence from the eleventh Five-Year Plan and green patents. Econ. Lett. 2020, 190, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Rehman, S.U.; García, F.J.S. Corporate social responsibility and environmental performance: The mediating role of environmental strategy and green innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 160, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavragani, A.; Nikolaou, I.E.; Tsagarakis, K.P. Open economy, institutional quality, and environmental performance:A macroeconomic approach. Sustainability 2016, 8, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhong, Z.; Peng, B. Can environmental regulation promote green innovation in heavily polluting enterprises? Empirical evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 30, 815–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Feng, L.; Li, J.; Wang, L. Environmental regulation, tenure length of officials, and green innovation of enterprises. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Shen, W.; Tan, Y.; Matac, L.M.; Samad, S. Environmental uncertainty, environmental regulation and enterprises green technological innovation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Fang, H.; Jacoby, G.; Li, G.; Wu, Z. Environmental regulations and innovation for sustainability? Moderating effect of political connections. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2022, 50, 100835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, W.B.; Shadbegian, R.J. Plant vintage, technology, and environmental regulation. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2003, 46, 384–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, B.; Peng, X.; Ouyang, M. Environmental regulation, green total factor productivity and the transformation of China’s industrial development mode—An empirical study based on data from 36 industrial industries. China Ind. Econ. 2013, 4, 56–68. [Google Scholar]

- Blackman, A.; Lahiri, B.; Pizer, W.; Planter, M.R.; Piña, C.M. Voluntary environmental regulation in developing countries: Mexico’s Clean Industry Program. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2010, 60, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petroni, G.; Bigliardi, B.; Galati, F. Rethinking the Porter Hypothesis: The Underappreciated Importance of Value Appropriation and Pollution Intensity. Rev. Policy Res. 2019, 36, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, G.; Mohnen, P. Revisiting the Porter hypothesis: An empirical analysis of Green innovation for the Netherlands. Econ. Innov. New Technol. 2016, 26, 62–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Huang, Y.; Li, J. The mechanism of influencing green technology innovation behavior: Evidence from Chinese construction enterprises. Buildings 2022, 12, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhou, J.; Xia, X.; Wang, Z. The mixed impact of environmental regulations and external financing constraints on green technological innovation of enterprise. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.S. Regulation by Shaming: Deterrence Effects of Publicizing Violations of Workplace Safety and Health Laws. Am. Econ. Rev. 2020, 110, 1868–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, N. The threshold effect of environmental regulation on the impact of regional technological innovation. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2012, 22, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zang, C.; Zhang, H. Spatial differences in the technological innovation effects of environmental regulations-an empirical analysis based on panel data of China from 2000–2013. Macroecon. Res. 2015, 11, 72–83. [Google Scholar]

- Stucki, T.; Woerter, M.; Arvanitis, S.; Peneder, M.; Rammer, C. How different policy instruments affect green product innovation: A differentiated perspective. Energy Policy 2018, 114, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.; Lin, D.; Cui, J. Can environmental equity trading market induce green innovation? -Evidence based on green patent data of listed companies in China. Econ. Res. 2018, 53, 129–143. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y. Research on green credit policies to enhance green innovation. Manag. World 2021, 37, 173–188. [Google Scholar]

- Seman, N.A.A.; Govindan, K.; Mardani, A.; Zakuan, N.; Saman, M.Z.M.; Hooker, R.E.; Ozkul, S. The mediating effect of green innovation on the relationship between green supply chain management and environmental performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. Corporate Social Responsibility Information Disclosure and Innovation Performance—Is based on the empirical research of Chinese listed companies in the era of compulsory disclosure. Sci. Sci. Technol. Manag. 2021, 42, 57–75. [Google Scholar]

- Karassin, O.; Bar-Haim, A. Multilevel corporate environmental responsibility. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 183, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, G.; Pini, M. Environmental vs. Social Responsibility in the Firm. Evidence from Italy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cox, P.; Wicks, P.G. Institutional Interest in Corporate Responsibility: Portfolio Evidence and Ethical Explanation. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 103, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, J.L.; Berrone, P.; Phan, P.H. Corporate governance and environmental performance: Is there really a link? Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 885–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, L.; Sun, J.; He, P. Can public participation constraints promote green technological innovation of Chinese enterprises? The moderating role of government environmental regulatory enforcement. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 174, 121198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A.J.; Welker, M. Social disclosure, financial disclosure and the cost of equity capital. Account. Organ. Soc. 2001, 26, 602–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berchicci, L.; Dowell, G.; King, A.A. Environmental capabilities and corporate strategy: Exploring acquisitions among us manufacturing firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doshi, A.R.; Dowell, G.W.; Toffel, M.W. Toffel. How Firms Respond To Mandatory Information Disclosure. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 1215–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dhaliwal, D.S.; Radhakrishnan, S.; Tsang, A.; Yang, Y.G. Nonfinandal Disclosure and Analyst Forecast Accuracy: International Evidence on Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure. Account. Rev. 2012, 87, 723–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ning, J. Can the compulsory social responsibility information disclosure drive the green transformation of enterprises?—Evidence based on the green patent data of listed companies in China. Audit. Econ. Res. 2020, 35, 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Belmonte-Ureña, L.J.; Plaza-Úbeda, J.A.; Vazquez-Brust, D.; Yakovleva, N. Circular economy, degrowth and green growth as pathways for research on sustainable development goals: A global analysis and future agenda. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 185, 107050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemingway, C.A.; Maclagan, P.W. Maclagan. Managers’ Personal Values as Drivers of Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 50, 154–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Wang, K. The “disguise effect” of social responsibility information disclosure and the risk of listed company crash—Comes from the DID-PSM analysis of the Chinese stock market. Manag. World 2017, 11, 146–157. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.C.; Hung, M.; Wang, Y. The effect of mandatory CSR disclosure on firm profitability and social externalities: Evidence from China. J. Account. Econ. 2018, 65, 169–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, X.; Xu, X.; Xu, R. Investigation of management opportunistic behavior under social responsibility compulsory disclosure—Based on the empirical evidence of A-share listed companies. J. Manag. Sci. 2018, 21, 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ikram, A.; Li, Z.F.; Minor, D. CSR-contingent executive compensation contracts. J. Bank. Financ. 2019, 23, 105655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Thibodeau, C. CSR-Contingent Executive Compensation Incentive and Earnings Management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Q.; Xiao, Z. Heterogeneous environmental regulation tools and enterprise green innovation incentives—Evidence from the green patents of listed enterprises. Econ. Res. 2020, 55, 192–208. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, F.; Wang, Z.; Bai, J. The Dual Effect of Environmental Regulation on Technological Innovation—An Empirical Research Based on the Dynamic Panel Data of Jiangsu Manufacturing Industry. Ind. Econ. China 2013, 7, 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- You, D.; Li, L. Environmental regulation intensity, cutting-edge technology gap and enterprise green technology innovation. Soft Sci. 2022, 36, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Min, W. An Empirical Study on the Impact of Environmental Regulation on the Efficiency of Green Technology Innovation. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 248–250, 02029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Geng, H.; Xu, G.; Chen, J. Research on the Impact of Environmental Regulation on Green Technology Innovation. China’s Population. Resour. Environ. 2019, 29, 168–176. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, K.; King, K.; Fang, X. Does the environmental regulation cause the pollution to move nearby? Econ. Res. 2017, 52, 44–59. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, P.; Chatterjee, C. Does environmental regulation indirectly induce upstream innovation? New evidence from India. Res. Policy 2017, 46, 939–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P.M.; Li, Y.; Richardson, G.D.; Vasvari, F.P. Revisiting the relation between environmental performance and environmental disclosure: An empirical analysis. Account. Organ. Soc. 2007, 33, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, K.A.; Romi, A.M.; Sánchez, D.; Sanchez, J.M. The influence of corporate social responsibility on investment efficiency and innovation. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 2019, 46, 494–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoepner, A.; Oikonomou, I.; Scholtens, B.; Schröder, M. The Effects of Corporate and Country Sustainability Characteristics on The Cost of Debt: An International Investigation. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 2016, 43, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Aghion, P.; Bursztyn, L.; Hemous, D. The Environment and Directed Technical Change. Am. Econ. Rev. 2012, 102, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- LópezPuertas-Lamy, M.; Desender, K.; Epure, M. Corporate social responsibility and the assessment by auditors of the risk of material misstatement. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 2017, 44, 1276–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benlemlih, M.; Girerd-Potin, I. Corporate social responsibility and firm financial risk reduction: On the moderating role of the legal environment. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 2017, 44, 1137–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesta, L.; Vona, F.; Nicolli, F. Environmental policies, competition and innovation in renewable energy. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2014, 67, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briones Penalver, A.J.; Bernal Conesa, J.A.; Carmen, D.N. Analysis of Corporate Social Responsibility in Spanish Agri-business and Its Influence on Innovation and Performance. Corporate. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. Which type of ownership enterprise in China is the most innovative? World Econ. 2012, 35, 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, G.; Zhuo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J. Will ESG information disclosure increase corporate value? Financ. Account. Commun. 2022, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zhang, W.; Bi, Q. Will environmental taxes force companies to make green innovation? Audit. Econ. Res. 2019, 34, 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Javeed, S.A.; Teh, B.H.; Ong, T.S.; Chong, L.L.; Abd Rahim, M.F.B.; Latief, R. How Does Green Innovation Strategy Influence Corporate Financing? Corporate Social Responsibility and Gender Diversity Play a Moderating Role. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palčič, I.; Prester, J. Impact of Advanced Manufacturing Technologies on Green Innovation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Lin, S. Characteristics and heterogeneity of Environmental Regulation on Enterprise Green Technology Innovation- -Based on Green Patent Data of Chinese Listed Companies. Sci. Res. 2021, 39, 909–919. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, A. Environmental tax collection, social responsibility undertaking and enterprise green innovation. Econ. Theory Econ. Manag. 2022, 42, 67–85. [Google Scholar]

- Du, L.; Zhao, Y.; Tao, K.; Lin, W. The compound effect of environmental regulation and governance transformation on green competitiveness improvement—Is based on the empirical evidence of Chinese industry. Econ. Res. 2019, 54, 106–120. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Xia, L. Environmental protection investment, quality of environmental information disclosure and enterprise value. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2019, 39, 256–264. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, R.; Chen, X.; Qian, L. Heterogeneous environmental regulation, government support and enterprise green innovation efficiency. Financ. Trade Res. 2022, 33, 79–93. [Google Scholar]

| Type of Variable | Variable Name | Variable Symbol | Variable-Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explained variable | Enterprise green innovation | GI | The natural logarithm of green patent applications plus 1 |

| explanatory variable | Environmental regulation intensity | ERI | The ratio of the exhaust gas emission to the total industrial output |

| The ratio of the wastewater discharge to the total industrial output | |||

| The ratio of the solid waste pollution to the total industrial output | |||

| Moderator variable | Social responsibility information | CSR | Shareholder liability index |

| Employee responsibility index | |||

| The supplier, customer, and consumer equity liability index | |||

| Environmental responsibility index | |||

| Social responsibility index evaluation | |||

| Control variable | Scale | Ln_Size | The total assets of the enterprise at the end of the year take the natural log |

| Profitability | ROA | Net profit is divided by the average total assets | |

| Debt capacity | Lev | Total liabilities at the end of the year are divided by the total assets at the end of the year | |

| Growth ability | Growth | Main business revenue growth rate | |

| Enterprise maturity | Ln_Age | Natural logarithm of listing years plus 1 | |

| Equity concentration | Top1 | The ratio of the largest shareholder | |

| Board size | Ln_Board | The total number of enterprise board of directors is the natural log | |

| Proportion of enterprise independent directors | Ind | The proportion of the number of independent directors to the total number of the board of directors | |

| Enterprise executive compensation | Ln_Pay | The sum of the three most paid executives takes the natural logarithm | |

| Property nature | State | The value of state-owned enterprises is 1, otherwise the value is 0 |

| Variable | N | Mean | Median | Min | Max | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GI | 7205 | 1.315 | 1.099 | 0.000 | 7.386 | 1.328 |

| ERI | 7205 | 0.173 | 0.033 | 0.000 | 5.891 | 0.393 |

| CSR | 7205 | 0.508 | 0.106 | 0.023 | 4.093 | 0.957 |

| Ln_Pay | 7205 | 14.345 | 14.323 | 11.132 | 17.746 | 0.709 |

| Ln_Board | 7205 | 2.162 | 2.197 | 1.386 | 2.833 | 0.188 |

| Growth | 7205 | 0.222 | 0.155 | −0.467 | 17.773 | 0.573 |

| Ln_Size | 7205 | 22.351 | 22.190 | 19.541 | 28.636 | 1.240 |

| Top1 | 7205 | 0.343 | 0.320 | 0.034 | 0.900 | 0.146 |

| Ln_Age | 7205 | 2.314 | 2.485 | 0.000 | 3.689 | 0.705 |

| ROA | 7205 | 0.042 | 0.037 | −1.125 | 0.478 | 0.066 |

| Ind | 7205 | 0.370 | 0.333 | 0.200 | 0.800 | 0.055 |

| Lev | 7205 | 0.432 | 0.432 | 0.008 | 2.155 | 0.199 |

| GI | ERI | CSR | Ln_Pay | Ln_Board | Growth | Ln_Size | Top1 | Ln_Age | ROA | Ind | Lev | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GI | 1 | |||||||||||

| ERI | −0.14 *** | 1 | ||||||||||

| CSR | 0.05 *** | 0.11 *** | 1 | |||||||||

| Ln_Pay | 0.33 *** | −0.13 *** | 0.06 *** | 1 | ||||||||

| Ln_Board | 0.13 *** | 0.06 *** | 0.13 *** | 0.08 *** | 1 | |||||||

| Growth | 0.03 ** | −0.009 | 0.05 *** | 0.04 *** | 0.03 *** | 1 | ||||||

| Ln_Size | 0.54 *** | 0.02 * | 0.16 *** | 0.48 *** | 0.27 *** | 0.05 *** | 1 | |||||

| Top1 | 0.08 *** | 0.10 *** | 0.12 *** | 0.03 *** | 0.05 *** | 0.10 *** | 0.25 *** | 1 | ||||

| Ln_Age | 0.17 *** | −0.13 *** | −0.05 *** | 0.23 *** | 0.04 *** | −0.07 ** | 0.31 *** | −0.06 ** | 1 | |||

| ROA | −0.03 *** | 0.06 *** | 0.11 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.07 *** | 0.06 *** | 0.02 * | 0.16 *** | −0.14 *** | 1 | ||

| Ind | 0.03 *** | −0.003 | 0.02 * | 0.04 *** | −0.42 *** | 0.01 | 0.06 *** | 0.07 *** | 0.04 *** | −0.04 ** | 1 | |

| Lev | 0.27 *** | 0.03 *** | 0.07 *** | 0.06 *** | 0.14 *** | 0.05 *** | 0.45 *** | 0.04 *** | 0.27 *** | −0.38 ** | 0.02 | 1 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GI | GI | GI | GI | GI | GI | |

| ERI2 | 0.097 *** (5.26) | 0.068 *** (3.26) | 0.040 *** (4.83) | 0.069 *** (10.12) | 0.028 ** (2.97) | |

| ERI | −0.501 *** (−6.99) | −0.370 *** (−4.47) | −0.479 *** (−7.25) | −0.921 *** (−13.21) | −0.402 *** (−5.40) | |

| CSR | 0.016 * (0.89) | 0.057 ** (2.28) | ||||

| CSR × ERI | −0.168 *** (−3.16) | −0.233 ** (−2.83) | ||||

| CSR × ERI2 | 0.042 *** (2.61) | 0.049 ** (2.49) | ||||

| L.ERI2 | 0.121 *** (4.15) | |||||

| L.ERI | −0.455 *** (−6.58) | |||||

| Ln_Pay | 0.093 *** (4.27) | 0.096 *** (4.12) | 0.097 *** (4.42) | 0.275 *** (9.45) | 0.120 *** (3.62) | 0.277 *** (9.47) |

| Ln_Board | 0.157 ** (2.02) | 0.139 (1.67) | 0.167 ** (2.15) | 0.277 ** (2.41) | −0.121 (−1.11) | 0.264 ** (2.29) |

| Growth | −0.027 (−1.23) | −0.027 (−1.13) | −0.028 (−1.27) | −0.006 (−0.63) | −0.079 ** (−2.23) | −0.005 (−0.59) |

| Ln_Size | 0.570 *** (39.23) | 0.583 *** (37.97) | 0.571 *** (38.80) | 0.580 *** (24.70) | 0.696 *** (36.10) | 0.575 *** (24.19) |

| Top1 | −0.167 * (−1.84) | −0.174 (−1.79) | −0.165 * (−1.81) | 0.074 (0.61) | −0.437 ** (−3.17) | 0.074 (0.61) |

| Ln_Age | −0.020 (−0.90) | −0.032 ** (−1.21) | −0.014 (−0.66) | −0.054 (−1.81) | 0.049 (1.37) | −0.053 * (−1.76) |

| ROA | 0.198 (0.89) | 0.226 *** (0.98) | 0.192 (0.87) | 1.601 *** (5.57) | 0.893 ** (2.59) | 1.565 *** (5.44) |

| Ind | −0.114 (0.18) | −0.021 (−0.08) | 0.073 (0.29) | 0.940 * (2.43) | −1.177 *** (−3.41) | 0.882 ** (2.27) |

| Lev | 0.286 *** (3.58) | 0.336 *** (3.97) | 0.274 *** (3.44) | 0.508 *** (4.50) | −0.104 (−0.91) | 0.503 *** (4.46) |

| _cons | −12.858 *** (−13.535) | −13.081 *** (−35.27) | −12.987 *** (−36.50) | −14.216 *** (−25.57) | −12.373 *** (−25.72) | −14.091 *** (−24.89) |

| Industry | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Year | control | control | control | control | control | control |

| Adj R2 | 0.389 | 0.465 | 0.390 | 0.406 | 0.529 | 0.406 |

| N | 7205 | 6584 | 7205 | 4033 | 3172 | 4033 |

| Hypothesis | Significance | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| H1a: There is a U-shaped curve relationship between the intensity of environmental regulation and enterprises’ green innovation. | Significant | U |

| H1b: Environmental regulation with a lag period has a more significant impact on green innovation. | Significant | U |

| H2: CSR disclosure has a positive regulatory effect on the relationship be-tween environmental regulation and enterprise green innovation. | Significant | positive |

| H3: Environmental regulation and CSR disclosure has a greater impact on the green innovation of non-state-owned enterprises. | Significant | positive |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GI | GI | GI | |

| ERI2 | 0.057 *** | 0.030 *** | 0.167 *** |

| (7.40) | (3.33) | (8.17) | |

| ERI | −0.738 *** | −0.499 *** | −2.276 *** |

| (−10.49) | (−6.02) | (−9.33) | |

| CSR | 0.158 *** | ||

| (6.14) | |||

| CSR × ERI | −0.459 *** | ||

| (−6.23) | |||

| CSR × ERI2 | 0.097 ** | ||

| (4.41) | |||

| Pay | 0.217 *** | 0.210 *** | 0.364 *** |

| (6.72) | (6.47) | (4.35) | |

| Board | 0.305 ** | 0.301 ** | 0.484 * |

| (2.67) | (2.64) | (1.79) | |

| Growth | −0.082 *** | −0.081 *** | −0.056 |

| (−6.35) | (−6.29) | (−0.72) | |

| Size | 0.346 *** | 0.332 *** | 0.849 *** |

| (16.13) | (15.32) | (15.03) | |

| Top1 | 0.286 ** | 0.292 ** | −0.339 |

| (2.13) | (2.19) | (−1.01) | |

| Ln_Age | −0.154 *** | −0.151 *** | −0.025 ** |

| (−4.77) | (−4.65) | (−0.28) | |

| ROA | 1.835 *** | 1.786 *** | 1.515 * |

| (3.96) | (5.47) | (1.72) | |

| Ind | 0.150 | 0.095 | 0.264 |

| (2.02) | (0.25) | (0.31) | |

| Lev | 0.098 | 0.076 | 0.100 |

| (0.83) | (0.65) | (0.36) | |

| _cons | −8.548 *** | −8.216 *** | −24.692 *** |

| (−16.77) | (−15.67) | (−18.17) | |

| Industry | control | control | control |

| Year | control | control | control |

| Adj R2 | 0.1544 | 0.1599 | 0.2845 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, X.; Jing, R.; Lu, F. Environmental Regulation, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Disclosure and Enterprise Green Innovation: Evidence from Listed Companies in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14771. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214771

Xu X, Jing R, Lu F. Environmental Regulation, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Disclosure and Enterprise Green Innovation: Evidence from Listed Companies in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(22):14771. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214771

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Xiumei, Ruolan Jing, and Feifei Lu. 2022. "Environmental Regulation, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Disclosure and Enterprise Green Innovation: Evidence from Listed Companies in China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 22: 14771. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214771

APA StyleXu, X., Jing, R., & Lu, F. (2022). Environmental Regulation, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Disclosure and Enterprise Green Innovation: Evidence from Listed Companies in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 14771. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214771