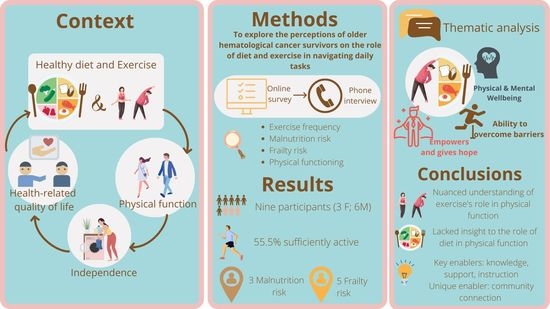

Perceptions of Older Adults with Hematological Cancer on Diet and Exercise Behavior and Its Role in Navigating Daily Tasks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Sampling

2.2. Recruitment and Consent

2.3. Data Collection and Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Role of Diet and Exercise in the Ability to Engage in Daily Tasks

3.1.1. Theme 1. Beliefs on the Impact of Diet and Exercise on Physical and Mental Wellbeing

I think healthy food creates a healthy body. What we eat today walks and talks tomorrow. That’s my attitude. If I’m gonna look after myself, and I want tomorrow to be good, I’ll eat well today.

If you eat [takeaway meal] every day, you’re not gonna get anywhere … it is not the type of food that will substantiate a decent level of vitamins and minerals and everything that you need for your body. … the right food gives you the power for your muscles to work properly and the amount of antioxidants and things like that. So, it’s still a matter of building muscle, but the right food is basically the building blocks of your muscle.

I find that it [exercise] makes me a little bit more alert, ‘cause one of the things that I have found is that my speech has been affected and I find doing the exercise must do something to the brain to help me to put sentences and that together’. Going through chemo treatment, you lose a lot of balance and exercise helps you get that balance back.

3.1.2. Theme 2. The Ability to Overcome Barriers to Adhere to a Healthy Diet and Exercise Behavior

Subtheme 2.1: Having a Routine and Being Organized

It’s developing routine, routine is very important. So, sort of, wake up in the morning, do the juice, do the meditate, then exercise, then breakfast. It’s in that slot.

I’ve never really had much fast food, as growing up as a kid, we never had the opportunity to have fast food and I’ve just kept that going through my adult life.

I’ve always been an active person and that’s just the way I am. I mean, I just do it; it’s probably more of a habit now too. We just get up and we just do it and we feel the benefits from it.

… when I was feeling lousy you couldn’t get me interested in doing any exercise, I had problems walking from one place to another, so it didn’t even come into my mind to even try and exercise. Now I just do the normal things around the place … I’ve never done any formal exercise.

Subtheme 2.2: Self-Determination versus Dependence

Sometimes, depending on my physical and emotional state, cooking is difficult; that’s why sometimes it’s good for me to do the big cook at lunchtime. I guess it’s a function of age and also the treatments I’ve done. I get tired and sometimes lack the motivation. But you know, there’s a part of me too that works with: ‘Oh Craig you’re looking after yourself and that’s good’.(Craig)

I’ve got a dog, which helps tremendously [to exercise]. I’ve got a husband who also is a good walker and keen on exercise, so I have a companion who I walk with every day. So that’s really good.(Louise)

I really need to start eating a lot healthier, but I’m hoping that’ll come. With all the chemo, you lose a lot of taste in your taste buds so your good, healthy food, tastes $@#!... where all the lovely, sweet biscuits and the chocolates don’t.

I understand the importance of both of them [diet and exercise], but for me it’s just I have no energy compared to what I was before … It’s an absolute struggle to get up in the morning … and do anything at home … I plan an activity … and it might be a half an hour activity … and I can do literally nothing else for the rest of the day … I’m trying to get back into becoming more active but I’m finding it very difficult in that I have no energy.(George)

Depends on need. What I need to do. If I need to walk to the letter box. If I need to walk from one end of the hospital to the other. Even if I am out of breath, you know, I need to do it...

Subtheme 2.3: Knowledge and Access to Information

After I went to the cancer expo on Saturday, I found that it was really informative around exercise and nutrition … It’s given me a little bit of … a wakeup call, it made me really understand that they are the two things that’s going to get me through this. They are the two things that I have to pick up on a little bit more than what I’m doing now.

I can only go on what I read or see on television as such.

3.1.3. Theme 3. Taking Back Control and Having Hope for the Future

Right from the beginning, I realized that the only thing I was going to be in control of was my physical health and mental health … I’m not in charge of what’s going in as far as drugs go, but I am in control of what food I’m eating. So, I think I’m pretty strong-minded and especially in exercise and eating well, that to me is what I’m in control of.

The outcome of eating healthy is that one of these days that, along with the exercise of course, I may be able to get off this medication altogether. I’d like to give it the best shot I can …

My long-term goal is to commence that [martial arts] next year, so I’ve given myself the rest of this year to get fitter so that I could undertake that.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allart-Vorelli, P.; Porro, B.; Baguet, F.; Michel, A.; Cousson-Gélie, F. Haematological cancer and quality of life: A systematic literature review. Blood Cancer J. 2015, 5, e305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Immanuel, A. Quality of life in survivors of adult haematological malignancy. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2019, 28, e13067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, R.; Zwaal, C.; Green, E.; Tomasone, J.R.; Loblaw, A.; Petrella, T. Exercise for people with cancer: A systematic review. Curr. Oncol. 2017, 24, e290–e315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rock, C.L.; Doyle, C.; Demark-Wahnefried, W.; Meyerhardt, J.; Courneya, K.S.; Schwartz, A.L.; Bandera, E.V.; Hamilton, K.K.; Grant, B.; McCullough, M.; et al. Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2012, 62, 243–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, S.; Wurz, A.; Bradshaw, A.; Saunders, S.; West, M.A.; Brunet, J. Physical Activity and Quality of Life in Cancer Survivors: A Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Research. Cancers 2017, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochems, S.H.J.; Van Osch, F.H.M.; Bryan, R.T.; Wesselius, A.; van Schooten, F.J.; Cheng, K.K.; Zeegers, M.P. Impact of dietary patterns and the main food groups on mortality and recurrence in cancer survivors: A systematic review of current epidemiological literature. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e014530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscaritoli, M.; Arends, J.; Bachmann, P.; Baracos, V.; Barthelemy, N.; Bertz, H.; Bozzetti, F.; Hütterer, E.; Isenring, E.; Kaasa, S.; et al. ESPEN practical guideline: Clinical Nutrition in cancer. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 2898–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, L.; Nguo, K.; Furness, K.; Porter, J.; Huggins, C.E. Association between skeletal muscle mass and quality of life in adults with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 839–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, L.E.; Ni Bhuachalla, E.B.; Power, D.G.; Cushen, S.J.; James, K.; Ryan, A.M. Loss of skeletal muscle during systemic chemotherapy is prognostic of poor survival in patients with foregut cancer. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2018, 9, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahler, S.; Ghazi, N.G.; Singh, A.D. Principles and complications of chemotherapy. In Clinical Ophthalmic Oncology: Basic Principles; Singh, A.D., Damato, B.E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 129–142. [Google Scholar]

- Coa, K.I.; Epstein, J.B.; Ettinger, D.; Jatoi, A.; McManus, K.; Platek, M.E.; Price, W.; Stewart, M.; Teknos, T.N.; Moskowitz, B. The impact of cancer treatment on the diets and food preferences of patients receiving outpatient treatment. Nutr. Cancer 2015, 67, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boltong, A.; Keast, R.; Aranda, S. Experiences and consequences of altered taste, flavour and food hedonics during chemotherapy treatment. Support Care Cancer 2012, 20, 2765–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.S.; Zhao, F.; Fisch, M.J.; O’Mara, A.M.; Cella, D.; Mendoza, T.R.; Cleeland, C.S. Prevalence and characteristics of moderate to severe fatigue: A multicenter study in cancer patients and survivors. Cancer 2014, 120, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, T.; Nakano, J.; Ishii, S.; Natsuzako, A.; Hirase, T.; Sakamoto, J.; Okita, M. Characteristics of muscle function and the effect of cachexia in patients with haematological malignancy. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2019, 28, e12956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillis, C.; Richer, L.; Fenton, T.R.; Gramlich, L.; Keller, H.; Culos-Reed, S.N.; Sajobi, T.T.; Awasthi, R.; Carli, F. Colorectal cancer patients with malnutrition suffer poor physical and mental health before surgery. Surgery 2021, 170, 841–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, G.; Wan, W.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Yin, J. Correlation between the Charlson comorbidity index and skeletal muscle mass/physical performance in hospitalized older people potentially suffering from sarcopenia. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, I.H. Sarcopenia: Origins and Clinical Relevance. J. Nutr. 1997, 127, 990S–991S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, K.H.; Courneya, K.S.; Matthews, C.; Demark-Wahnefried, W.; Galvão, D.A.; Pinto, B.M.; Irwin, M.L.; Wolin, K.Y.; Segal, R.J.; Lucia, A.; et al. American College of Sports Medicine Roundtable on Exercise Guidelines for Cancer Survivors. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2010, 42, 1409–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battaglini, C.L.; Hackney, A.C.; Garcia, R.; Groff, D.; Evans, E.; Shea, T. The Effects of an Exercise Program in Leukemia Patients. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2009, 8, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shallwani, S.; Dalzell, M.A.; Sateren, W.; O’Brien, S. Exercise compliance among patients with multiple myeloma undergoing chemotherapy: A retrospective study. Support Care Cancer 2015, 23, 3081–3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallance, J.K.; Courneya, K.S.; Jones, L.W.; Reiman, T. Differences in quality of life between non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma survivors meeting and not meeting public health exercise guidelines. Psychooncology 2005, 14, 979–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alibhai, S.M.H.; Durbano, S.; Breunis, H.; Brandwein, J.M.; Timilshina, N.; Tomlinson, G.A.; Oh, P.I.; Culos-Reed, S.N. A phase II exercise randomized controlled trial for patients with acute myeloid leukemia undergoing induction chemotherapy. Leuk. Res. 2015, 39, 1178–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craike, M.; Hose, K.; Livingston, P.M. Physical activity participation and barriers for people with multiple myeloma. Support Care Cancer 2013, 21, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elshahat, S.; Treanor, C.; Donnelly, M. Factors influencing physical activity participation among people living with or beyond cancer: A systematic scoping review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallerand, J.R.; Rhodes, R.E.; Walker, G.J.; Courneya, K.S. Correlates of meeting the combined and independent aerobic and strength exercise guidelines in hematologic cancer survivors. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzan, A.J.; Newberg, A.B.; Cho, W.C.; Monti, D.A. Diet and nutrition in cancer survivorship and palliative care. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 917647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denova-Gutiérrez, E.; Méndez-Sánchez, L.; Muñoz-Aguirre, P.; Tucker, K.L.; Clark, P. Dietary Patterns, Bone Mineral Density, and Risk of Fractures: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadeh, M.; Prinelli, F.; Vetrano, D.L.; Xu, W.; Welmer, A.-K.; Dekhtyar, S.; Fratiglioni, L.; Calderón-Larrañaga, A. Mobility and muscle strength trajectories in old age: The beneficial effect of Mediterranean diet in combination with physical activity and social support. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, R.; Villani, A. Greater adherence to a Mediterranean Diet is associated with better gait speed in older adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2019, 32, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, E.S.; Rice, N.; Kingston, E.; Kelly, A.; Reynolds, J.V.; Feighan, J.; Power, D.G.; Ryan, A.M. A national survey of oncology survivors examining nutrition attitudes, problems and behaviours, and access to dietetic care throughout the cancer journey. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2021, 41, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keaver, L.; McGough, A.M.; Du, M.; Chang, W.; Chomitz, V.; Allen, J.D.; Attai, D.J.; Gualtieri, L.; Zhang, F.F. Self-Reported Changes and Perceived Barriers to Healthy Eating and Physical Activity among Global Breast Cancer Survivors: Results from an Exploratory Online Novel Survey. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, 233–241.e238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, T.; Cheetham, T.; Müller, A.M.; Slodkowska-Barabasz, J.; Wilde, L.; Krusche, A.; Richardson, A.; Foster, C.; Watson, E.; Little, P.; et al. Exploring cancer survivors’ views of health behaviour change: “Where do you start, where do you stop with everything?”. Psychooncology 2018, 27, 1816–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.; Zhu, J.; Velazquez, J.; Bernardo, R.; Garcia, J.; Rovito, M.; Hines, R.B. Evaluation of Diet Quality Among American Adult Cancer Survivors: Results From 2005–2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, A.C.; Smith, K.C.; Shuster, M.; Coa, K.I.; Caulfield, L.E.; Helzlsouer, K.J.; Peairs, K.S.; Shockney, L.D.; Stoney, D.; Hannum, S. “We’re Just Not Prepared for Eating Over Our Whole Life”: A Mixed Methods Approach to Understanding Dietary Behaviors Among Longer Term Cancer Survivors. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2018, 17, 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alibhai, S.M.H.; Breunis, H.; Timilshina, N.; Brignardello-Petersen, R.; Tomlinson, G.; Mohamedali, H.; Gupta, V.; Minden, M.D.; Li, M.; Buckstein, R.; et al. Quality of life and physical function in adults treated with intensive chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia improve over time independent of age. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2015, 6, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandelowski, M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res. Nurs. Health 2000, 23, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, A.; Hannes, K.; Harden, A.; Noyes, J.; Harris, J.; Tong, A. COREQ (Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies). In Guidlines for Reporting Health Research: A User’s Manual; Moher, D., Altman, D.G., Schulz, K.F., Simera, I., Wager, E., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 214–226. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government. Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines, Adults (18 to 64 Years). Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/health-topics/physical-activity-and-exercise/physical-activity-and-exercise-guidelines-for-all-australians/for-adults-18-to-64-years (accessed on 24 April 2021).

- Brazier, J.E.; Harper, R.; Jones, N.M.; O’Cathain, A.; Thomas, K.J.; Usherwood, T.; Westlake, L. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: New outcome measure for primary care. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 1992, 305, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godin, G. The Godin-Shephard Leisure-Time Physical Activity Questionnaire. Health Fit. J. Can. 2011, 4, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Raîche, M.; Hébert, R.; Dubois, M.-F. PRISMA-7: A case-finding tool to identify older adults with moderate to severe disabilities. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2008, 47, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, M.; Capra, S.; Bauer, J.; Banks, M. Development of a valid and reliable malnutrition screening tool for adult acute hospital patients. Nutrition 1999, 15, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Janz, N.K.; Becker, M.H. The Health Belief Model: A decade later. Health Educ. Q. 1984, 11, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michie, S.; Richardson, M.; Johnston, M.; Abraham, C.; Francis, J.; Hardeman, W.; Eccles, M.P.; Cane, J.; Wood, C.E. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: Building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 46, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheill, G.; Guinan, E.; Neill, L.O.; Hevey, D.; Hussey, J. The views of patients with metastatic prostate cancer towards physical activity: A qualitative exploration. Support Care Cancer 2018, 26, 1747–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; Blizzard, L.; Fell, J.; Giles, G.; Jones, G. Associations Between Dietary Nutrient Intake and Muscle Mass and Strength in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: The Tasmanian Older Adult Cohort Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2010, 58, 2129–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arends, J.; Bachmann, P.; Baracos, V.; Barthelemy, N.; Bertz, H.; Bozzetti, F.; Fearon, K.; Hütterer, E.; Isenring, E.; Kaasa, S.; et al. ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in cancer patients. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 11–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dent, E.; Lien, C.; Lim, W.S.; Wong, W.C.; Wong, C.H.; Ng, T.P.; Woo, J.; Dong, B.; de la Vega, S.; Hua Poi, P.J.; et al. The Asia-Pacific Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Frailty. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 564–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, L.; Pringle, D.; Su, J.; Shen, X.; Mahler, M.; Niu, C.; Charow, R.; Tiessen, K.; Lam, C.; Halytskyy, O.; et al. Patterns, perceptions, and perceived barriers to physical activity in adult cancer survivors. Support. Care Cancer 2018, 26, 3755–3763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frikkel, J.; Götte, M.; Beckmann, M.; Kasper, S.; Hense, J.; Teufel, M.; Schuler, M.; Tewes, M. Fatigue, barriers to physical activity and predictors for motivation to exercise in advanced Cancer patients. BMC Palliat. Care 2020, 19, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sremanakova, J.; Sowerbutts, A.M.; Todd, C.; Cooke, R.; Burden, S. Systematic Review of Behaviour Change Theories Implementation in Dietary Interventions for People Who Have Survived Cancer. Nutrients 2021, 13, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.F.; Wyld, D.; Brown, T.; Eastgate, M.A. Dietary patterns and attitudes in cancer patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, e22055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.C.; Coa, K.I.; Klassen, A.C. A qualitative study of dietary discussions as an emerging task for cancer clinicians. SAGE Open Med. 2016, 4, 2050312116665935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ligibel, J.A.; Jones, L.W.; Brewster, A.M.; Clinton, S.K.; Korde, L.A.; Oeffinger, K.C.; Bender, C.M.; Tan, W.; Merrill, J.K.; Katta, S.; et al. Oncologists’ Attitudes and Practice of Addressing Diet, Physical Activity, and Weight Management with Patients with Cancer: Findings of an ASCO Survey of the Oncology Workforce. J. Oncol. Pract. 2019, 15, e520–e528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loeliger, J.; Dewar, S.; Kiss, N.; Dumbrell, J.; Elliott, A.; Kaegi, K.; Kelaart, A.; McIntosh, R.; Swan, W.; Stewart, J. Co-design of a cancer nutrition care pathway by patients, carers and health professionals: The CanEAT pathway. Res. Sq. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demark-Wahnefried, W.; Aziz, N.M.; Rowland, J.H.; Pinto, B.M. Riding the crest of the teachable moment: Promoting long-term health after the diagnosis of cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 5814–5830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwath, C.C. Applying the transtheoretical model to eating behaviour change: Challenges and opportunities. Nutr. Res. Rev. 1999, 12, 281–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bron, D.; Aurer, I.; André, M.P.E.; Bonnet, C.; Caballero, D.; Falandry, C.; Kimby, E.; Soubeyran, P.; Zucca, E.; Bosly, A.; et al. Unmet needs in the scientific approach to older patients with lymphoma. Haematologica 2017, 102, 972–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.S.; Steele, R.; Coyle, J. Lifestyle issues for colorectal cancer survivors—Perceived needs, beliefs and opportunities. Support. Care Cancer 2013, 21, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskarinec, G.; Murphy, S.; Shumay, D.M.; Kakai, H. Dietary changes among cancer survivors. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2001, 10, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Séguin Leclair, C.; Lebel, S.; Westmaas, J.L. Can Physical Activity and Healthy Diet Help Long-Term Cancer Survivors Manage Their Fear of Recurrence? Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 647432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Host, A.; McMahon, A.-T.; Walton, K.; Charlton, K. Factors Influencing Food Choice for Independently Living Older People—A Systematic Literature Review. J. Nutr. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2016, 35, 67–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebar, A.L.; Dimmock, J.A.; Jackson, B.; Rhodes, R.E.; Kates, A.; Starling, J.; Vandelanotte, C. A systematic review of the effects of non-conscious regulatory processes in physical activity. Health Psychol. Rev. 2016, 10, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, E.; Kellett, J.; Bacon, R.; Naumovski, N. Food Habits of Older Australians Living Alone in the Australian Capital Territory. Geriatrics 2020, 5, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Total Group (n = 9) |

|---|---|

| Age | 67 ± 2 |

| Reported height (cm) | 172 ± 2.9 |

| Reported weight (kg) | 75.6 ± 5.2 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.2 ± 1.0 |

| PRISMA-7 score | 2.6 ± 0.4 |

| Malnutrition screening score | 0 (0; 2) |

| Time since diagnosis (months) | 12 (10.5; 20) |

| n | |

| Marital status | |

| Married/cohabitating | 8 |

| Single/widowed | 1 |

| Employment status | |

| Employed | 2 |

| Unemployed | 1 |

| Retired | 6 |

| Cancer type | |

| Multiple myeloma | 3 |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | 1 |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 1 |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 1 |

| Refractory Hodgkin lymphoma | 2 |

| Relapse follicular lymphoma | 1 |

| Treatment stage | |

| Induction | 1 |

| Consolidation | 1 |

| Maintenance | 4 |

| Second-line | 3 |

| History of stem cell transplant | |

| Yes | 4 |

| No | 5 |

| Pseudonym Gender | Age | Time Since Diagnosis | Cancer Diagnosis | Physical Activity Level | Frailty Risk | PF 1 | Malnutrition Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| George, male | 61 | 12 months | Multiple myeloma | Sufficiently active | At risk | 20 | Yes |

| Samuel, male | 67 | 9 months | Chronic myeloid leukemia | Moderately active | At risk | 35 | No |

| Kevin, male | 67 | 5 months | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | Sufficiently active | Not at risk | 85 | No |

| Andrew, male | 69 | 13 months | Hodgkin lymphoma | Insufficiently active | At risk | 20 | No |

| David, male | 70 | 12 months | Multiple myeloma | Insufficiently active | At risk | 55 | Yes |

| Craig, male | 71 | 24 months | Refractory follicular lymphoma | Sufficiently active | At risk | 40 | No |

| Suzanne, female | 72 | 6 years | Multiple myeloma | Sufficiently active | Not at risk | 40 | No |

| Louise, female | 73 | 16 months | Myelodysplastic syndrome | Sufficiently active | Not at risk | 95 | No |

| Barbara, female | 76 | 12 months | Hodgkin lymphoma | Moderately active | Not at risk | 65 | Yes |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Colton, A.; Smith, M.A.; Broadbent, S.; Rune, K.T.; Wright, H.H. Perceptions of Older Adults with Hematological Cancer on Diet and Exercise Behavior and Its Role in Navigating Daily Tasks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15044. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215044

Colton A, Smith MA, Broadbent S, Rune KT, Wright HH. Perceptions of Older Adults with Hematological Cancer on Diet and Exercise Behavior and Its Role in Navigating Daily Tasks. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(22):15044. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215044

Chicago/Turabian StyleColton, Alana, Monica A. Smith, Suzanne Broadbent, Karina T. Rune, and Hattie H. Wright. 2022. "Perceptions of Older Adults with Hematological Cancer on Diet and Exercise Behavior and Its Role in Navigating Daily Tasks" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 22: 15044. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215044

APA StyleColton, A., Smith, M. A., Broadbent, S., Rune, K. T., & Wright, H. H. (2022). Perceptions of Older Adults with Hematological Cancer on Diet and Exercise Behavior and Its Role in Navigating Daily Tasks. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 15044. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215044