Predictors of Length of Hospitalization and Impact on Early Readmission for Mental Disorders

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sample, Sources, and Design

2.2. Study Variables

2.3. Analysis

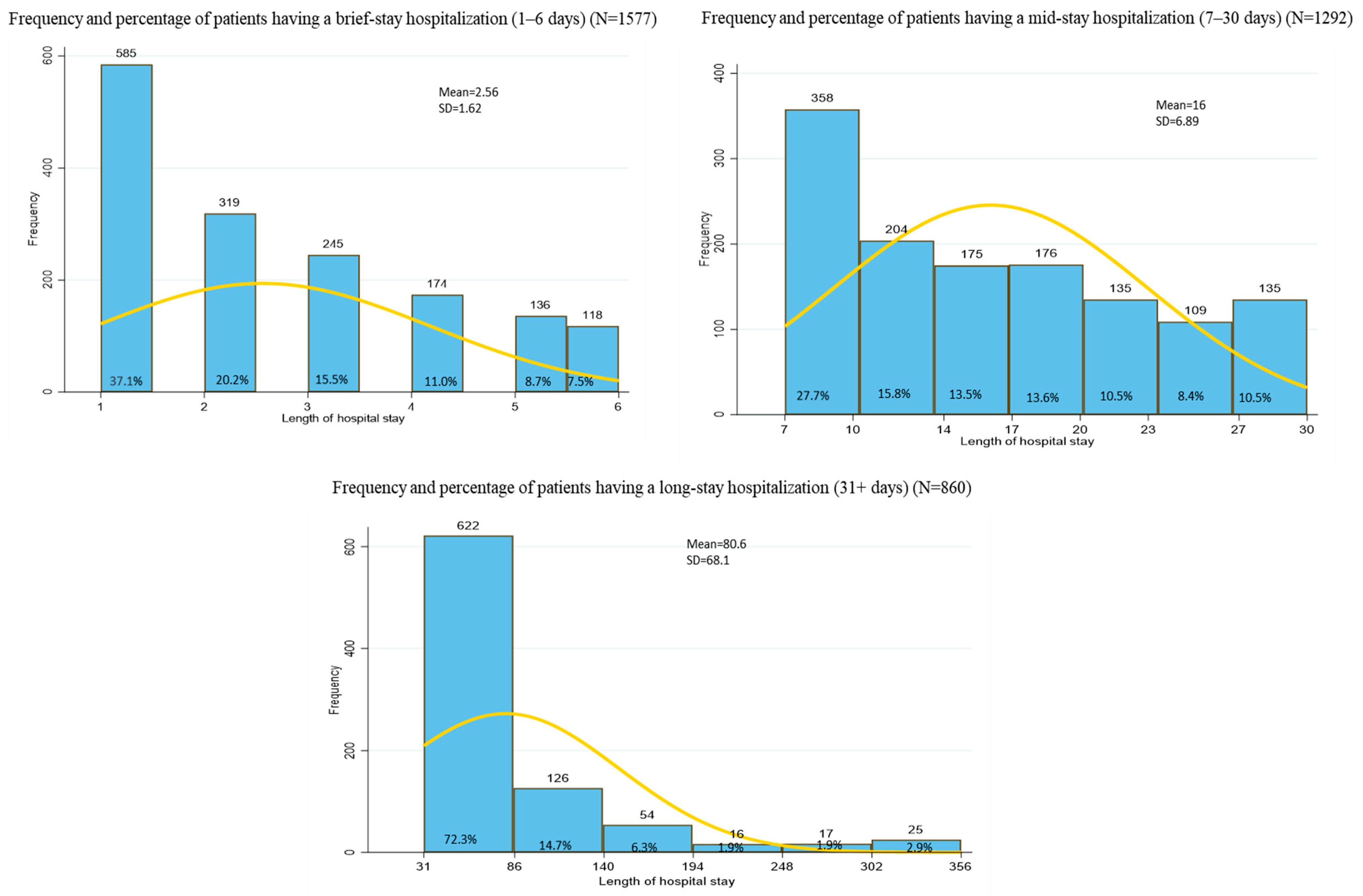

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIC | Akaike’s Information Criterion |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| ED | emergency department |

| GP | general practitioner |

| ICC | intraclass correlation coefficient |

| ICD | International Classification of Diseases |

| MD | mental disorder |

| SRD | substance-related disorder |

| RAMQ | Quebec Health Insurance Plan (Régie de l’assurance maladie du Québec) |

| VIF | variance inflation factor |

Appendix A

| Diagnoses | International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) | International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Canada (ICD-10-CA) |

|---|---|---|

| Mental Disorders (MD) a | ||

| Common MD | ||

| Depressive disorders | 3004 (neurotic depression) *; 311, 3119 * (depressive disorder, not elsewhere classified) | F320–F323 (major depressive disorder, single episode); F328 (other depressive episodes); F329 (depressive episode, unspecified); F330–F334 (major depressive disorder, recurrent); F338 (other recurrent depressive disorders); F339 (recurrent depressive disorder, unspecified); F348 (other persistent mood [affective] disorders); F380, F381 (persistent mood [affective] disorder, unspecified); F388 (other specified mood [affective] disorders); F39 (unspecified mood [affective] disorders); F412 * (mixed anxiety and depressive disorder) * |

| Anxiety disorders | 300 (except 3004); 3000 (anxiety states); 3002 (phobic anxiety disorders); 3003 (obsessive-compulsive disorder); 3001 (hysteria); 3006 (other anxiety disorder); 313 (disturbance of emotions specific to childhood and adolescence) | F40 (phobic anxiety disorders); F41(other anxiety disorders); F42 (obsessive-compulsive disorder); F45 (somatoform disorders); F48 (other neurotic disorders); F93, F94 (disturbance of emotions specific to childhood and adolescence) |

| Adjustment disorders | 3090 (brief depressive reaction); 3092 (adjustment reaction with predominant disturbance of other emotions, include: abnormal separation anxiety); 3093 (adjustment reaction with predominant disturbance of conduct); 3094 (adjustment reaction with predominant disturbance of other emotions and conduct); 3098 (other specified adjustment reactions); 3099 (unspecified adjustment reaction) | F430 (acute stress reaction); F431 (post-traumatic stress disorder); F432 (adjustment disorders); F438 (other reactions to severe stress); F439 (reaction to severe stress, unspecified) |

| Other MD | 314 (attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder); 2930, 2931 (transient organic psychotic conditions); 2940, 2941 (other organic psychotic conditions); 2990, 2991 *, 2998, 2999 (pervasive developmental disorders); 290, 2941, 3310, 3312 (dementia); 3020–3029 (sexual deviations and disorders); 3070–3079 (special symptoms or syndromes, not elsewhere classified include anorexia nervosa, tics); 312 (disturbance of conduct, not elsewhere classified); 3150–3159 (specific delays in development); 316 (psychic factors associated with diseases classified elsewhere); 317–318 (mental retardation) | F900; F901; F908; F909 (attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder); F060–F069 (other mental disorders due to known physiological condition); F840, F841, F842, F843, F844, F845 (pervasive developmental disorders); F00x–F03, F051, G30, G311(dementia); F500–F502 (eating disorders); F520–F529 (sexual dysfunction, not caused by organic disorder or disease); F510–F515 (nonorganic sleep disorders); F950–F952, F958, F959 (tic disorders); F980–F986, F988, F989 (other behavioral and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence); F630–F633, F638, F639 (habit and impulse disorders); F70–73, F78, F79 (mental retardation) |

| Serious MD | ||

| Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders | 295 * (schizophrenic disorders); 297 * (paranoid states); 298 * (other nonorganic psychoses) | F20 * (schizophrenic disorders); F22 * (persistent delusional disorders); F23 (acute and transient psychotic disorders); F24 * (induced delusional disorder); F25 * (schizoaffective disorders); F28 * (other psychotic disorder not due to a substance or known physiological condition); F29 * (unspecified psychosis not due to a substance or known physiological condition); F448 (other dissociative and conversion disorders); F481 (depersonalization—derealization syndrome) |

| Bipolar disorders | 2960–2966 (manic disorders); 2968 (other affective psychoses); 2969 (unspecified affective psychoses) | F300–F302, F308, F309 (manic episode); F310–F317, F318, 319 (bipolar episode) |

| Personality disorders | 3010 (paranoid personality disorder); 3011 (affective personality disorder); 3012 (schizoid disorder); 3013, 3014 (obsessive-compulsive personality disorder); 3015 (histrionic personality disorder); 3016 (dependent personality disorder); 3017 (antisocial personality disorder); 3018 (other personality disorders); 3019 (unspecified personality disorder) | F600 (paranoid personality disorder); F61 (mixed and other personality disorders); F340 (cyclothymic disorder); F341 (dysthymic disorder); F601 (schizoid personality); F603 (borderline personality disorder); F605 (obsessive-compulsive personality disorder); F604 (histrionic personality disorder); F607 (dependent personality disorder); F602 (antisocial personality disorder); F609 (unspecified personality disorder); F21 (schizotypal personality); F606 (avoidant personality disorder); F608 (other specified personality disorders); F681 (factitious disorder); F688 (other specified disorders of adult personality and behaviour); F69 (unspecified disorder of adult personality and behaviour) |

| Suicide attempta,b | X60–Y09, Y870, Y871, Y35–Y36, Y890, Y891 | |

| Substance-related disorders a | ||

| Alcohol-related disorders | 3030 *, 3039 *, 3050 * (alcohol abuse or dependence); 2910 *, 2918 * (alcohol withdrawal), 2911 *–2915 *, 2919 *, 3575, 4255, 5353, 5710–5713 (alcohol-induced disorders); 9800, 9801, 9808, 9809 (alcohol intoxication) | F101 *, F102 * (alcohol abuse or dependence); F103, F104 * (alcohol withdrawal); F105–F109, K700 *–K704 *, K709 *, G621 *, I426, K292 *, K852, K860, E244, G312, G721, O354 (alcohol-induced disorders); F100 *, T510, T511 *, T518, T519 (alcohol intoxication) |

| Cannabis-related disorder | 3043, 3052 (cannabis abuse or dependence) | F121, F122 (cannabis abuse or dependence); F123–F129 (cannabis-induced disorders); F120, T407 (cannabis intoxication) |

| Drug-related disorders other than cannabis | 3040–3042, 3044–3049, 3053–3057, 3059 (drug abuse or dependence); 292.0 (drug withdrawal); 2921, 2922, 2928, 2929 (drug-induced disorders); 9650, 9658, 9670, 9676, 9678, 9679, 9694–9699, 9708, 9820, 9828 (drug intoxication) | F111, F131, F141, F151, F161, F181, F191, F112, F132, F142, F152, F162, F182, F192 (drug abuse or dependence); F113–F114, F133–F134, F143–F144, F153–F154, F163–F164, F183–F184, F193–F194 (drug withdrawal) F115–F119, F135–F139, F145–F149, F155–F159, F165–F169, F185–F189, F195–F199 (drug-induced disorders); F110, F130, F140, F150, F160, F180, F190, T400-T406, T408, T409, T423, T424, T426, T427, T435, T436, T438, T439, T509, T528, T529 (drug intoxication) |

| Chronic physical illnessesa,c | ||

| Renal failure | 4030, 4031, 4039, 4040, 4041, 4049, 585, 586, 5880, V420, V451, V56 | I120, I131, N18, N19, N250, Z49, Z940, Z992 |

| Cerebrovascular illnesses | 430–438 | G45, G46, I60–I69 |

| Neurological illnesses | 3319, 3320, 3321, 3334, 3335, 3339, 334–335, 3362, 340, 341, 345, 3481, 3483, 7803, 7843 | G10–G12, G13, G20, G21–G22, G254, G255, G312, G318, G319, G32, G35, G36, G37, G40, G41, G931, G934, R470, R56 |

| Endocrine illnesses (hypothyroidism; fluid electrolyte disorders and obesity) | 2409, 243, 244, 2461, 2468; 2536, 276; 2780 | E00, E01, E02, E03, E890; E222, E86, E87; E66 |

| Any tumor with or without metastasis (solid tumor without metastasis; lymphoma) | 140–172, 174, 175, 179–195, 196–199; 200, 201, 202, 2030, 2386, 2733 | C00–C26, C30–C34, C37–C41, C43, C45-C58, C60–C76, C77–C79, C80; C81-C85, C88, C900, C902, C96 |

| Chronic pulmonary illnesses | 490–505, 5064, 5081, 5088 | I278, I279, J40–J47, J60–J64, J65, J66, J67, J684, J701, J703 |

| Diabetes, complicated and uncomplicated | 2500–2502, 2503; 2504–2509 | E102-E108, E112-E118, E132-E138, E142-E148; E100, E101, E109, E110, E111, E119, E130, E131, E139, E140, E141, E149 |

| Cardiovascular illnesses (congestive heart failure; cardiac arrhythmias; valvular illnesses; peripheral vascular illnesses; myocardial infarction; hypertension and pulmonary circulation illnesses) | 4021, 4041, 428; 4260, 4267, 4269,4270–4274,4276–4279, 7850, V450, V533; 394–397, 424,7463–7466, V422, V433; 093, 440, 441, 4431–4439, 4471, 5571, 5579, V434; 4109, 4129; 4010, 4011, 4019, 4020, 4021, 4029, 4050, 405,4051, 4059, 4372; 4150, 4151, 416; 4170, 4178, 4179 | I099, I110, I130, I132, I255, I420, I425–I429, I43, I50, P290; I441–I443, I456, I459, I47–I49, R000, R001, R008, T821, Z450, Z950; A520, I70–I72, I730, I731, I738, I739, I771, I790, K551, K558, K559, Z958, Z959; I05–I08, I091, I098, I34–I39, Q230–Q233, Q238, Q239, Z952, Z953, Z954, I210–I214, I219, I220, I221, I228, I229, I252; I101, I100, I11, I1500, I1501, I1510, I1511, I1521, I1581, I1590, I1591, I674; I26, I27, I280, I288, I289 |

| Other chronic physical illness categories (blood loss anemia; ulcer illnesses; liver illnesses; AIDS/HIV; rheumatoid arthritis/collagen vascular illnesses, coagulopathy; weight loss, paralysis; deficiency anemia) | 2800, 2809; 286, 2871, 2873–2875; 5317, 5319, 5327, 5329, 5337, 5339, 5347, 5349; 0702, 0703, 0704, 0705, 4560–4562, 5723, 5728, 5733, 5734, 5739, V427; 042–044; 1361, 446; 7010, 7100–7104, 7105, 7108, 7109, 7112, 714, 7193, 720, 725, 7285, 7288, 7293; 260–263, 7832, 7994; 3341, 342, 343, 3440–3446, 3448, 3449; 2801, 2809, 281, 2859 | D500; K257, K259, K267, K269, K277, K279, K287, K289; B20–B24; D65–D68, D691, D693-D696; B18, I85, I864, I982, K700- K703, K709 K711, K713–K715, K716, K717, K721, K729, K73, K74, K754, K760, K761, K763, K764, K765, K766, K768, K769, Z944; L900, L940, L941, L943, M05, M06, M08, M120, M123, M30, M31, M32–M35, M45, M460, M461, M468, M469; G041, G114, G80, G81, G82, G83; E40–E46, R634, R64, D51–D53, D63, D649; D501, D508; D509 |

References

- Pauselli, L.; Verdolini, N.; Bernardini, F.; Compton, M.T.; Quartesan, R. Predictors of Length of Stay in an Inpatient Psychiatric Unit of a General Hospital in Perugia, Italy. Psychiatr. Q. 2017, 88, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baeza, F.L.C.; da Rocha, N.S.; Fleck, M.P.A. Readmission in psychiatry inpatients within a year of discharge: The role of symptoms at discharge and post-discharge care in a Brazilian sample. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2018, 51, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, S.; Charlemagne, S.J.; Gilman, A.B.; Alemi, Q.; Smith, R.L.; Tharayil, P.R.; Freeman, K. Post-discharge services and psychiatric rehospitalization among children and youth. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2010, 37, 433–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Boaz, T.L.; Becker, M.A.; Andel, R.; Van Dorn, R.A.; Choi, J.; Sikirica, M. Risk factors for early readmission to acute care for persons with schizophrenia taking antipsychotic medications. Psychiatr. Serv. 2013, 64, 1225–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulloch, A.D.; David, A.S.; Thornicroft, G. Exploring the predictors of early readmission to psychiatric hospital. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2016, 25, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moore, C.O.; Moonie, S.; Anderson, J. Factors Associated with Rapid Readmission Among Nevada State Psychiatric Hospital Patients. Community Ment. Health J. 2019, 55, 804–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Unplanned hospital re-admissions for patients with mental disorders. In Health at a Glance 2013: OECD Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassemo, E.; Myklebust, L.H.; Salazzari, D.; Kalseth, J. Psychiatric readmission rates in a multi-level mental health care system—A descriptive population cohort study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donisi, V.; Tedeschi, F.; Salazzari, D.; Amaddeo, F. Pre- and post-discharge factors influencing early readmission to acute psychiatric wards: Implications for quality-of-care indicators in psychiatry. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2016, 39, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, G. Predictors of 30-day Postdischarge Readmission to a Multistate National Sample of State Psychiatric Hospitals. J. Healthc. Qual. 2019, 41, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Jiang, F.; Tang, Y.; Needleman, J.; Guo, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, H.; Liu, Y. Factors associated with 30-day and 1-year readmission among psychiatric inpatients in Beijing China: A retrospective, medical record-based analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rieke, K.; McGeary, C.; Schmid, K.K.; Watanabe-Galloway, S. Risk Factors for Inpatient Psychiatric Readmission: Are There Gender Differences? Community Ment. Health J. 2016, 52, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golay, P.; Morandi, S.; Conus, P.; Bonsack, C. Identifying patterns in psychiatric hospital stays with statistical methods: Towards a typology of post-deinstitutionalization hospitalization trajectories. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2019, 54, 1411–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, L.J.; Harris, V.; Newman, L.; Beck, A. Rapid and frequent psychiatric readmissions: Associated factors. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2017, 21, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, L.; Harris, V.; Evans, L.J.; Beck, A. Factors Associated with Length of Stay in Psychiatric Inpatient Services in London, UK. Psychiatr. Q. 2018, 89, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gopalakrishna, G.; Ithman, M.; Malwitz, K. Predictors of length of stay in a psychiatric hospital. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2015, 19, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossley, N.; Sweeney, B. Patient and service-level factors affecting length of inpatient stay in an acute mental health service: A retrospective case cohort study. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, G.A.; Baldessarini, R.J.; Ongur, D.; Centorrino, F. Factors associated with length of psychiatric hospitalization. Compr. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, J.; Li, A.; Tobin, J.; Weinstein, I.S.; Harimoto, T.; Lanctot, K.L. Predictors of readmission to a psychiatry inpatient unit. Compr. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.; Holsinger, B.; Flanagan, J.V.; Ayers, A.M.; Hutchison, S.L.; Terhorst, L. Effectiveness of a Brief Care Management Intervention for Reducing Psychiatric Hospitalization Readmissions. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2016, 43, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.H.; Termine, D.J.; Moore, A.A.; Sherman, S.E.; Palamar, J.J. Medical multimorbidity and drug use among adults in the United States. Prev. Med. Rep. 2018, 12, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, J.; McCrone, P.; Patel, A.; Kaier, K.; Normann, C. Predictors of length of stay in psychiatry: Analyses of electronic medical records. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rylander, M.; Colon-Sanchez, D.; Keniston, A.; Hamalian, G.; Lozano, A.; Nussbaum, A.M. Risk Factors for Readmission on an Adult Inpatient Psychiatric Unit. Qual. Manag. Health Care 2016, 25, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, J.A.; Burke-Miller, J.K.; Jonikas, J.A.; Aranda, F.; Santos, A. Factors associated with 30-day readmissions following medical hospitalizations among Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 291, 113168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mark, T.L.; Tomic, K.S.; Kowlessar, N.; Chu, B.C.; Vandivort-Warren, R.; Smith, S. Hospital readmission among medicaid patients with an index hospitalization for mental and/or substance use disorder. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2013, 40, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Régie de L’assurance Maladie du Québec. Nombre de Médecins Montant Total et Montant Moyen Selon la Catégorie de Médecins, le Groupe de Spécialités, la Spécialité et le Mode de Rémunération; Services Médicaux: Québec, QC, Canada, 2017; Available online: https://www4.prod.ramq.gouv.qc.ca/IST/CD/CDF_DifsnInfoStats/CDF1_CnsulInfoStatsCNC_iut/RappPDF.aspx?TypeImpression=pdf&NomPdf=CBB7R05A_SM24_2017_0_O.PDF (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Barros, R.E.; Marques, J.M.; Santos, J.L.; Zuardi, A.W.; Del-Ben, C.M. Impact of length of stay for first psychiatric admissions on the ratio of readmissions in subsequent years in a large Brazilian catchment area. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2016, 51, 575–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfil-Garza, B.A.; Belaunzaran-Zamudio, P.F.; Gulias-Herrero, A.; Zuniga, A.C.; Caro-Vega, Y.; Kershenobich-Stalnikowitz, D.; Sifuentes-Osornio, J. Risk factors associated with prolonged hospital length-of-stay: 18-year retrospective study of hospitalizations in a tertiary healthcare center in Mexico. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baek, H.; Cho, M.; Kim, S.; Hwang, H.; Song, M.; Yoo, S. Analysis of length of hospital stay using electronic health records: A statistical and data mining approach. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0195901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pampalon, R.; Hamel, D.; Gamache, P.; Raymond, G. A deprivation index for health planning in Canada. Chronic Dis. Can. 2009, 29, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simard, M.; Dubé, M.; Myles, G.; Sirois, C. La Prévalence de la Multimorbidité au Québec: Portrait pour L’année 2016–2017; Institut National de Santé Publique Du Québec: Québec, QC, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rahme, E.; Low, N.C.P.; Lamarre, S.; Daneau, D.; Habel, Y.; Turecki, G.; Bonin, J.P.; Morin, S.; Szkrumelak, N.; Singh, S.; et al. Correlates of Attempted Suicide from the Emergency Room of 2 General Hospitals in Montreal, Canada. Can. J. Psychiatry 2016, 61, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, H.P.; Marshall, R.E.; Rogers, W.H.; Safran, D.G. Primarye physician visit continuity: A comparison of patient-reported and administratively derived measures. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2008, 23, 1499–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vérificateur Général du Québec. Rapport du Vérificateur Général du Québec à l’Assemblée Nationale pour L’année 2015–2016. Vérification de L’optimisation des Ressources, Automne 2015; Vérificateur Général du Québec: Québec, QC, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dreiher, J.; Comaneshter, D.S.; Rosenbluth, Y.; Battat, E.; Bitterman, H.; Cohen, A.D. The association between continuity of care in the community and health outcomes: A population-based study. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2012, 1, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Breslau, N.; Reeb, K.G. Continuity of care in a university-based practice. J. Med. Educ 1975, 50, 965–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu-Ittu, R.; McCusker, J.; Ciampi, A.; Vadeboncoeur, A.M.; Roberge, D.; Larouche, D.; Verdon, J.; Pineault, R. Continuity of primary care and emergency department utilization among elderly people. CMAJ 2007, 177, 1362–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gaulin, M.; Simard, M.; Candas, B.; Lesage, A.; Sirois, C. Combined impacts of multimorbidity and mental disorders on frequent emergency department visits: A retrospective cohort study in Quebec, Canada. CMAJ 2019, 191, E724–E732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krieg, C.; Hudon, C.; Chouinard, M.C.; Dufour, I. Individual predictors of frequent emergency department use: A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marcus, S.C.; Chuang, C.C.; Ng-Mak, D.S.; Olfson, M. Outpatient Follow-Up Care and Risk of Hospital Readmission in Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder. Psychiatr. Serv. 2017, 68, 1239–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tulloch, A.D.; Fearon, P.; David, A.S. Length of stay of general psychiatric inpatients in the United States: Systematic review. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2011, 38, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoli, F.; Cavaleri, D.; Moretti, F.; Bachi, B.; Calabrese, A.; Callovini, T.; Cioni, R.M.; Riboldi, I.; Nacinovich, R.; Crocamo, C.; et al. Pre-Discharge Predictors of 1-Year Rehospitalization in Adolescents and Young Adults with Severe Mental Disorders: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Medicina 2020, 56, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basith, S.A.; Nakaska, M.M.; Sejdiu, A.; Shakya, A.; Namdev, V.; Gupta, S.; Mathialagan, K.; Makani, R. Substance Use Disorders (SUD) and Suicidal Behaviors in Adolescents: Insights From Cross-Sectional Inpatient Study. Cureus 2021, 13, e15602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepeda, M.S.; Schuemie, M.; Kern, D.M.; Reps, J.; Canuso, C. Frequency of rehospitalization after hospitalization for suicidal ideation or suicidal behavior in patients with depression. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 285, 112810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleury, M.J.; Grenier, G.; Vallee, C.; Aube, D.; Farand, L.; Bamvita, J.M.; Cyr, G. Implementation of the Quebec mental health reform (2005–2015). BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Olfson, M. Building the Mental Health Workforce Capacity Needed to Treat Adults with Serious Mental Illnesses. Health Affairs (Project Hope) 2016, 35, 983–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fleury, M.J.; Perreault, M.; Grenier, G.; Imboua, A.; Brochu, S. Implementing Key Strategies for Successful Network Integration in the Quebec Substance-Use Disorders Programme. Int. J. Integr. Care 2016, 16, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Galanter, M. Combining medically assisted treatment and Twelve-Step programming: A perspective and review. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 2018, 44, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Reif, S.; George, P.; Braude, L.; Dougherty, R.H.; Daniels, A.S.; Ghose, S.S.; Delphin-Rittmon, M.E. Residential treatment for individuals with substance use disorders: Assessing the evidence. Psychiatr. Serv. 2014, 65, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gouvernement du Québec. S’unir pour un Mieux-Être Collectif. Plan D’action Interministériel en Santé Mentale 2022–2026; Direction des Communications du Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux: Québec, QC, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Razzano, L.A.; Cook, J.A.; Yost, C.; Jonikas, J.A.; Swarbrick, M.A.; Carter, T.M.; Santos, A. Factors associated with co-occurring medical conditions among adults with serious mental disorders. Schizophr. Res. 2015, 161, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyapong, V.I.; Jabbar, F.; Conway, C. Shared care between specialised psychiatric services and primary care: The experiences and expectations of General Practitioners in Ireland. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2012, 16, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strelchuk, D.; Wiles, N.; Derrick, C.; Zammit, S.; Turner, K. Identifying patients at risk of psychosis: A qualitative study of GP views in South-West England. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2021, 71, e113–e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables Overall | Total Patients with Index (First Hospitalization in this 3-Year following Period) Hospitalization for Mental Health (MH) Reasons | Length of Hospitalization 2014-15 to 2016-17 | Bivariate Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brief Hospitalization: 1–6 Days | Mid-Stay Hospitalization: 7–30 Days | Long-Stay Hospitalization: ≥31 Days | |||

| N = 3729 (100%) | N = 1577 (42.3%) | N = 1292 (34.6 %) | N = 860 (23.1%) | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | p Value | |

| Sociodemographic characteristics (at index hospitalization for MH reasons, 2014-15 to 2016-17) | |||||

| Sex | 0.893 | ||||

| Men | 1916 (51) | 814 (52) | 657 (51) | 445 (52) | |

| Women | 1813 (49) | 763 (48) | 635 (49) | 415 (48) | |

| Age group | <0.001 | ||||

| ≤29 years | 1060 (28) | 496 (32) | 361 (28) | 203 (24) | |

| 30–64 years | 2236 (60) | 1002 (63) | 751 (58) | 483 (56) | |

| 65+ years | 433 (12) | 79 (5) | 180 (14) | 174 (20) | |

| Material Deprivation Index | 0.006 | ||||

| 1–3 | 1896 (50.8) | 774 (49.1) | 703 (54.4) | 419 (49) | |

| 4–5 or not assigned a | 1833 (49.2) | 803 (50.9) | 589 (45.6) | 441 (51) | |

| Social Deprivation Index | 0.088 | ||||

| 1–3 | 1198 (32) | 487 (31) | 445 (34) | 266 (31) | |

| 4–5 or not assigned a | 2531 (68) | 1090 (69) | 847 (66) | 594 (69) | |

| Clinical characteristics (from 2012-13 to index hospitalization for MH reasons, 2014-15 to 2016-17 or other if specified) | |||||

| Mental disorders (MD) b | |||||

| Common MD | 2191 (59) | 959 (61) | 758 (59) | 474 (55) | 0.024 |

| Serious MD | 2117 (57) | 749 (47) | 776 (60) | 592 (69) | <0.001 |

| Personality disorders | 658 (18) | 328 (21) | 203 (16) | 127 (15) | <0.001 |

| Substance-related disorder (SRD) | 814 (22) | 429 (27) | 250 (19) | 135 (16) | <0.001 |

| Chronic physical illnesses | 1565 (42) | 621 (39) | 545 (42) | 399 (46) | 0.004 |

| Elixhauser Comorbidity Index c | 0.676 | ||||

| 0 | 2810 (75) | 1188 (75) | 974 (75) | 648 (75) | |

| 1 | 331 (9) | 148 (9) | 115 (9) | 68 (8) | |

| 2 | 261 (7) | 114 (7) | 89 (7) | 58 (7) | |

| 3+ | 327 (9) | 127 (8) | 114 (9) | 86 (10) | |

| Co-occurring MD/chronic physical illnesses | 1539 (41) | 609 (39) | 536 (42) | 394 (46) | 0.003 |

| Co-occurring SRD/chronic physical illnesses | 361 (10) | 192 (12) | 113 (9) | 56 (7) | <0.001 |

| Co-occurring MD/SRD/chronic physical illnesses | 347 (9) | 184 (12) | 108 (8) | 55 (6) | <0.001 |

| Number of chronic physical illnesses, mean (SD)/median (IQR) | 2.34 (3.73)/ 0 (3.00) | 2.12 (3.54)/ 0 (3.00) | 2.29 (3.62)/ 0 (3.00) | 2.82 (4.16)/ 0 (3.00) | 0.004 |

| Number of MD/SRD diagnoses, mean (SD)/median (IQR) d | 1.78 (0.94)/ 2.00 (1.00) | 1.84 (0.99)/ 2.00 (1.00) | 1.75 (0.90)/ 2.00 (1.00) | 1.69 (0.88)/ 2.00 (1.00) | 0.002 |

| Suicidal behaviors (ideation or attempt related to index hospitalization, or emergency department use leading to index hospitalization) | 301 (8) | 196 (12) | 68 (5) | 37 (4) | <0.001 |

| Service use characteristics (within 12 months prior to patient index hospitalization for MH reasons, 2014-15 to 2016-17) | |||||

| Usual outpatient physicians e | <0.001 | ||||

| Usual general practitioner (GP) only | 683 (18) | 318 (20) | 250 (19) | 115 (13) | |

| Usual psychiatrist only | 949 (26) | 360 (23) | 310 (24) | 279 (33) | |

| Both usual GP and psychiatrist | 963 (26) | 385 (24) | 325 (25) | 253 (29) | |

| No usual physician | 1134 (30) | 514 (33) | 407 (32) | 213 (25) | |

| Number of consultations with usual GP f | 0.711 | ||||

| 0–1 consultation | 2083 (56) | 874 (55) | 717 (55) | 492 (57) | |

| 2 consultations | 523 (14) | 234 (15) | 177 (14) | 112 (13) | |

| 3+ consultations | 1123 (30) | 469 (30) | 398 (31) | 256 (30) | |

| Number of consultations with usual psychiatrist g | <0.001 | ||||

| 0 consultation | 1817 (49) | 832 (53) | 657 (51) | 328 (38) | |

| 1–2 consultations | 394 (10) | 169 (11) | 134 (10) | 91 (11) | |

| 3+ consultations | 1518 (41) | 576 (36) | 501 (39) | 441 (51) | |

| High continuity of physician care from both usual GP and psychiatrist ((≥0.80) h | 1549 (42) | 600 (38) | 529 (41) | 420 (49) | <0.001 |

| Psychosocial interventions in community healthcare centers (excluding GP consultations) | 0.006 | ||||

| 0 intervention | 2126 (57) | 909 (58) | 728 (56) | 489 (57) | |

| 1–2 interventions | 591 (16) | 268 (17) | 216 (17) | 107 (12) | |

| 3+ interventions | 1012 (27) | 400 (25) | 348 (27) | 264 (31) | |

| Previous hospitalization for MH reasons | 666 (18) | 271 (17) | 216 (17) | 179 (21) | 0.034 |

| High emergency department use (3+ visits) for MH reasons | 1251 (34) | 602 (38) | 410 (32) | 239 (28) | <0.001 |

| Variables | Total Patients at Index Hospitalization (First Hospitalization in This 3-Year following Period) | Readmission for Mental Health (MH) Reasons within 30 Days after Hospital Discharge | Bivariate Analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| N = 3729 (100%) | N = 321 (8.6%) | N = 3408 (91.4%) | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | p Value | |

| Length of hospital stay (main independent variable) | 0.006 | |||

| Brief-stay (1–6 days) | 1577 (42) | 160 (50) | 1417 (42) | |

| Mid-stay (7–30 days) | 1292 (35) | 106 (33) | 1186 (35) | |

| Long-stay (≥31 days) | 860 (23) | 55 (17) | 805 (24) | |

| Control variables | ||||

| Sociodemographic characteristics (at index hospitalization) | ||||

| Sex | 0.520 | |||

| Men | 1916 (51) | 165 (51) | 1751 (51) | |

| Women | 1813 (49) | 156 (49) | 1657 (49) | |

| Age group | 0.180 | |||

| ≤29 years | 1060 (28) | 102 (32) | 958 (28) | |

| 30–64 years | 2236 (60) | 190 (59) | 2046 (60) | |

| 65+ years | 433 (12) | 29 (9) | 404 (12) | |

| Material Deprivation Index | 0.006 | |||

| 1–3 | 1896 (51) | 141 (44) | 1755 (51) | |

| 4–5 or not assigned a | 1833 (49) | 180 (56) | 1653 (49) | |

| Social Deprivation Index | 0.043 | |||

| 1–3 | 1198 (32) | 89 (28) | 1109 (33) | |

| 4–5 or not assigned a | 2531 (68) | 232 (72) | 2299 (67) | |

| Clinical characteristics (from 2012-13 [1 April–31 March] to index hospitalization 2014-15 to 2016-17, or other period if specified) | ||||

| Mental disorders (MD) b | ||||

| Common MD | 2191 (59) | 191 (59) | 2000 (59) | 0.412 |

| Serious MD | 2117 (57) | 213 (66) | 1904 (56) | <0.001 |

| Personality disorders | 658 (18) | 86 (27) | 572 (17) | <0.001 |

| Substance-related disorders (SRD) | 814 (22) | 88 (27) | 726 (21) | 0.008 |

| Chronic physical illnesses | 1565 (42) | 168 (52) | 1397 (41) | <0.001 |

| Elixhauser Comorbidity Index c | 0.018 | |||

| 0 | 2810 (75) | 220 (68) | 2590 (76) | |

| 1 | 331 (9) | 32 (10) | 299 (9) | |

| 2 | 261 (7) | 32 (10) | 229 (7) | |

| 3+ | 327 (9) | 37 (12) | 290 (9) | |

| Co-occurring MD/chronic physical illnesses | 1539 (41) | 168 (52) | 1371 (40) | <0.001 |

| Co-occurring SRD/chronic physical illnesses | 361 (10) | 44 (14) | 317 (9) | 0.009 |

| Co-occurring MD/SRD/chronic physical illnesses | 347 (9) | 44 (14) | 303 (9) | 0.004 |

| Number of chronic physical illnesses, mean (SD)/median (IQR) | 2.34 (3.73)/0.00 (3.00) | 3.34 (4.56)/0.00 (3.00) | 2.25 (3.63)/0.00 (3.00) | <0.001 |

| Number of MD/SRD diagnoses, mean (SD)/median (IQR) d | 1.78 (0.94)/2.00 (1.00) | 1.77 (0.93)/2.00 (1.00) | 1.85 (1.00)/2.00 (1.00) | <0.001 |

| Suicidal behaviors (ideation, attempt related to index hospitalization, or emergency department visit leading to index hospitalization) | 301 (8) | 27 (8) | 274 (8) | 0.440 |

| Service use characteristics (within 30 days of discharge from index hospitalization, or another period if specified) | ||||

| At least one consultation received with any physician in outpatient care (general practitioner (GP) or psychiatrist) | 2883 (77) | 305 (95) | 2578 (76) | <0.001 |

| Psychosocial interventions in community healthcare centers | 939 (25) | 85 (27) | 854 (25) | 0.308 |

| Usual outpatient physicians (measured within 12 months prior to the 30-day period after discharge) e | <0.001 | |||

| GP only | 438 (12) | 24 (8) | 414 (12) | |

| Usual psychiatrist only | 1698 (45) | 200 (62) | 1498 (44) | |

| Both usual GP and psychiatrist | 474 (13) | 71 (22) | 403 (12) | |

| No usual physician | 1119 (30) | 26 (8) | 1093 (32) | |

| Variables | Brief-Stay Hospitalization: 1–6 Days | Mid-Stay Hospitalization: 7–30 Days | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | p-Value | 95% C. I | OR | p-Value | 95% C. I | |||

| Sociodemographic characteristics (at index hospitalization) | ||||||||

| Age (ref.: ≤29 years) | ||||||||

| 30–64 years | 0.95 | 0.604 | 0.77 | 1.17 | 0.94 | 0.619 | 0.76 | 1.17 |

| 65+ years | 0.20 | <0.001 | 0.14 | 0.29 | 0.62 | 0.003 | 0.45 | 0.85 |

| Clinical characteristics (from 2012-13 to index hospitalization, 2014-15 to 2016-17, or other period if specified) | ||||||||

| Mental disorders (MD) a | ||||||||

| Common MD | 0.98 | 0.839 | 0.81 | 1.18 | 1.08 | 0.416 | 0.89 | 1.31 |

| Serious MD | 0.45 | <0.001 | 0.37 | 0.55 | 0.77 | 0.013 | 0.63 | 0.94 |

| Personality disorders | 1.23 | 0.096 | 0.97 | 1.56 | 0.98 | 0.888 | 0.76 | 1.26 |

| Substance-related disorder (SRD) | 1.57 | <0.001 | 1.24 | 1.99 | 1.06 | 0.665 | 0.82 | 1.35 |

| Chronic physical illnesses b | 0.99 | 0.245 | 0.96 | 1.01 | 0.98 | 0.043 | 0.95 | 0.99 |

| Number of MD/SRD diagnoses c | 1.03 | 0.079 | 0.99 | 1.06 | 1.05 | 0.001 | 1.02 | 1.09 |

| Suicidal behaviors (ideation or attempt, related to index hospitalization, or emergency department visit leading to index hospitalization) | 2.56 | <0.001 | 1.76 | 3.73 | 1.11 | 0.618 | 0.73 | 1.69 |

| Service use characteristics (within 12 months prior to index hospitalization, or other period if specified) | ||||||||

| Usual outpatient physicians (ref.: no usual physician) d | ||||||||

| Usual general practitioner (GP) only | 1.67 | 0.002 | 1.22 | 2.31 | 1.44 | 0.025 | 1.05 | 1.99 |

| Usual psychiatrist only | 0.68 | 0.008 | 0.52 | 0.90 | 0.61 | 0.001 | 0.46 | 0.80 |

| Both usual GP and psychiatrist | 0.90 | 0.456 | 0.68 | 1.11 | 0.78 | 0.103 | 0.58 | 1.05 |

| High continuity of physician care from both usual GP and psychiatrist (ref. <0.80) e | 0.78 | 0.027 | 0.63 | 0.97 | 0.85 | 0.139 | 0.68 | 1.05 |

| High emergency department use (3+ visits) for mental health (MH) reasons (ref.: <3 visits) | 1.45 | <0.001 | 1.19 | 1.78 | 1.12 | 0.273 | 0.91 | 1.38 |

| Early Readmission following Hospital Discharge | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | OR | p-Value | 95% C. I | |

| Length of hospital stay (ref.: long-stay hospitalization: ≥31 days) | ||||

| Brief-stay hospitalization (1–6 days) | 1.83 | <0.001 | 1.30 | 2.57 |

| Mid-stay hospitalization (7–30 days) | 1.26 | 0.205 | 0.88 | 1.79 |

| Sociodemographic characteristics (at index hospitalization) | ||||

| Material Deprivation Index (ref.: 1–3) | ||||

| 4–5 or not assigned a | 1.28 | 0.047 | 1.01 | 1.64 |

| Social Deprivation Index (ref.: 1–3) | ||||

| 4–5 or not assigned a | 1.12 | 0.416 | 0.85 | 1.47 |

| Clinical characteristics (from 2012-13 to index hospitalization, 2014-15 to 2016-17, or other period if specified) | ||||

| Mental disorders (MD) b | ||||

| Serious MD | 1.05 | 0.729 | 0.80 | 1.37 |

| Personality disorders | 1.16 | 0.316 | 0.87 | 1.56 |

| Substance-related disorder (SRD) | 0.84 | 0.255 | 0.62 | 1.13 |

| Number of chronic physical illnesses c | 1.058 | <0.001 | 1.03 | 1.09 |

| Number of MD/SRD diagnoses d | 1.18 | <0.001 | 1.14 | 1.22 |

| Service use characteristics | ||||

| At least one consultation received with any physician in outpatient care (general practitioner (GP) or psychiatrist) (ref.: none) within 30 days of discharge from index hospitalization, or other period if specified | 1.73 | 0.188 | 0.76 | 3.93 |

| Usual outpatient physicians (ref.: no usual physician) (within 12 months prior to the 30-day period after discharge) e | ||||

| GP only | 1.71 | 0.175 | 0.79 | 3.70 |

| Usual psychiatrist only | 3.88 | <0.001 | 1.99 | 7.56 |

| Both usual GP and psychiatrist | 4.95 | <0.001 | 2.46 | 9.98 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gentil, L.; Grenier, G.; Vasiliadis, H.-M.; Fleury, M.-J. Predictors of Length of Hospitalization and Impact on Early Readmission for Mental Disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15127. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215127

Gentil L, Grenier G, Vasiliadis H-M, Fleury M-J. Predictors of Length of Hospitalization and Impact on Early Readmission for Mental Disorders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(22):15127. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215127

Chicago/Turabian StyleGentil, Lia, Guy Grenier, Helen-Maria Vasiliadis, and Marie-Josée Fleury. 2022. "Predictors of Length of Hospitalization and Impact on Early Readmission for Mental Disorders" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 22: 15127. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215127

APA StyleGentil, L., Grenier, G., Vasiliadis, H.-M., & Fleury, M.-J. (2022). Predictors of Length of Hospitalization and Impact on Early Readmission for Mental Disorders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 15127. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215127