A Treatment Model for Young Adults with Severe Mental Disorders in a Community Mental Health Center: The Crisalide Project and the Potential Space

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Transition to adult mental health services (TSMREE/CSM 17–19);

- Diagnostic, Therapeutic, and Assistance Pathways for Young Adults (PDTA-YA);

- High-intensity treatment center for young adults “Argolab2 Potential Space”.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Transition to Adult Mental Health Services (TSMREE/CSM 17–19)

2.2. Diagnostic, Therapeutic, and Assistance Pathways for Young Adults (PDTA-YA)

- Aged between 18 and 30 years;

- Absence of moderate or severe mental retardation;

- Exclusion of organic psychoses;

- Absence of substance addiction;

- Fulfillment of the criteria for one of the following ICD-9 diagnoses: (1) schizophrenia spectrum disorders; (2) affective psychosis, and (3) severe personality disorders.

2.3. High-Intensity Treatment Center for Young Adults “Argolab2 Potential Space”

3. Results

3.1. Transition to Adult Mental Health Services (TSMREE/CSM 17–19)

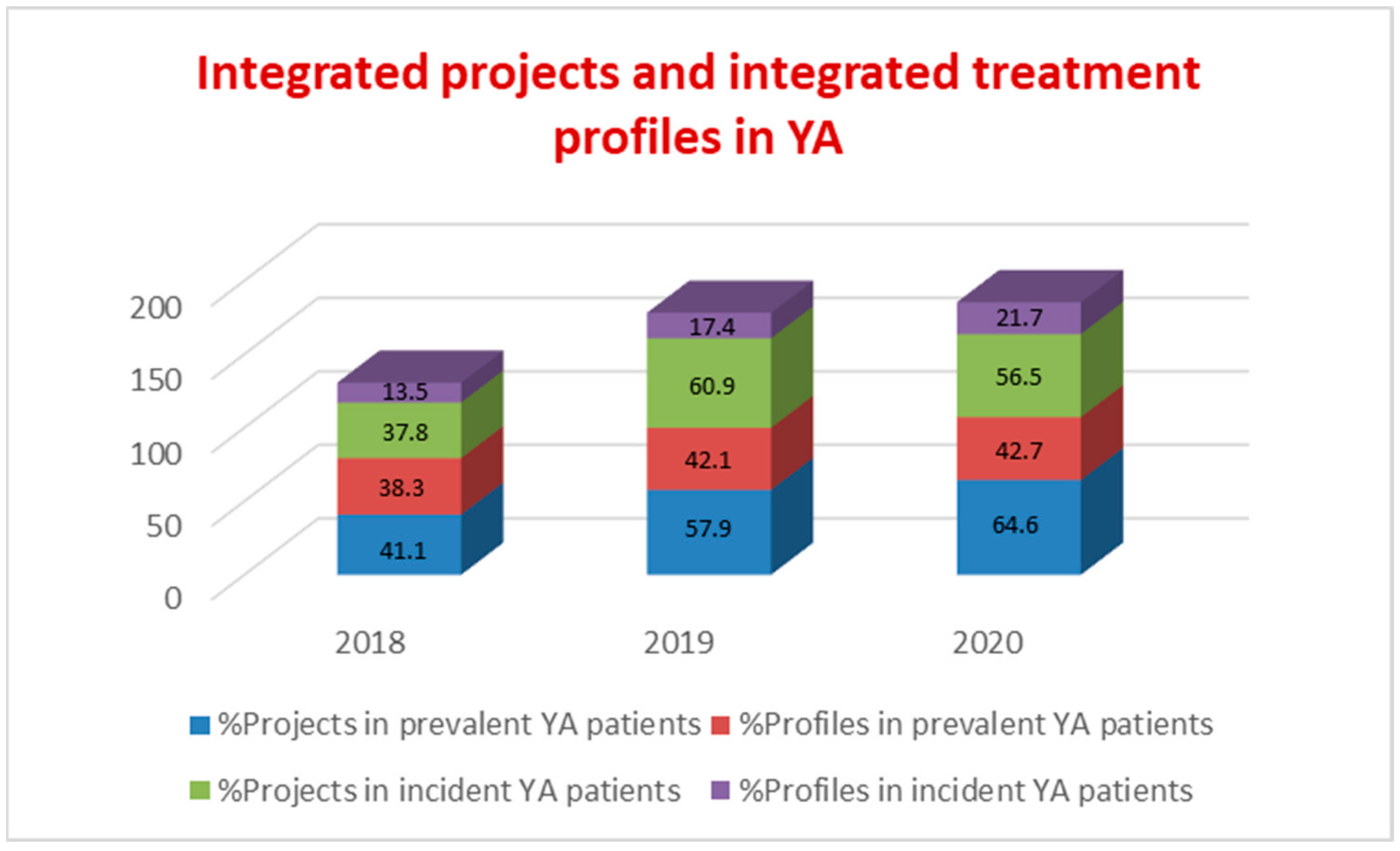

3.2. Diagnostic, Therapeutic, and Assistance Pathways for Young Adults (PDTA-YA)

3.3. High-Intensity Treatment Center for Young Adults “Argolab2 Potential Space”

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McGorry, P.; Nordentoft, M.; Simonsen, E. Introduction to “Early psychosis: A bridge to the future”. Br. J. Psychiatry 2005, 48, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ministero della Salute. Definizione Dei Percorsi Di Cura Da Attivare Nei Dipartimenti Di Salute Mentale Per I Disturbi Schizofrenici, I Disturbi Dell’umore E I Disturbi Gravi Di Personalità; Accordo Conferenza Unificata. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_2461_allegato.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2022).

- Kessler, R.C.; Amminger, G.P.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Alonso, J.; Lee, S.; Ustün, T.B. Age of onset of mental disorders: A review of recent literature. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2007, 20, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkbride, J.B.; Hameed, Y.; Ankireddypalli, G.; Ioannidis, K.; Crane, C.M.; Nasir, M.; Kabacs, N.; Metastasio, A.; Jenkins, O.; Espandian, A.; et al. The Epidemiology of First-Episode Psychosis in Early Intervention in Psychosis Services: Findings From the Social Epidemiology of Psychoses in East Anglia [SEPEA] Study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2017, 174, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penttilä, M.; Jääskeläinen, E.; Hirvonen, N.; Isohanni, M.; Miettunen, J. Duration of untreated psychosis as predictor of long-term outcome in schizophrenia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2014, 205, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schimmelmann, B.G.; Huber, C.G.; Lambert, M.; Cotton, S.; McGorry, P.D.; Conus, P. Impact of duration of untreated psychosis on pre-treatment, baseline, and outcome characteristics in an epidemiological first-episode psychosis cohort. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2008, 42, 982–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministero della Salute. Piano di Azioni Nazionale per la Salute Mentale. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_1905_allegato.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Singh, S.P.; Evans, N.; Sireling, L.; Stuart, H. Mind the gap: The interface between child and adult mental health services. Psychiatr. Bull. 2005, 29, 292–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signorini, G.; Singh, S.P.; Boricevic-Marsanic, V.; Dieleman, G.; Dodig-Ćurković, K.; Franic, T.; Gerritsen, S.E.; Griffin, J.; Maras, A.; McNicholas, F.; et al. Architecture and functioning of child and adolescent mental health services: A 28-country survey in Europe. Lancet Psychiatry 2017, 4, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, M.; O’Hara, L.; Tah, P.; Street, C.; Maras, A.; Ouakil, D.P.; Santosh, P.; Signorini, G.; Singh, S.P.; Tuomainen, H.; et al. A systematic review of the literature on ethical aspects of transitional care between child-and adult-orientated health services. BMC Med. Ethics 2018, 19, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Early Psychosis Association Writing Group. International clinical practice guidelines for early psychosis. Br. J. Psychiatry Suppl. 2005, 48, s120–s124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraceno, B. Liberare le Identità: Dalla Riabilitazione Psicosociale Alla Possibile Cittadinanza, 2nd ed.; Istituto Te Corá/Franco Basaglia: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ministero Della Salute, Analisi Dei Dati del Sistema Informativo per la Salute Mentale (SISM) Anno. 2020. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_3212_allegato.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- World Health Organization, Mental Health Action Plan. 2013–2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241506021 (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Yung Alison, R.; Cotter, J.; Mcgorry, P.D. Youth Mental Health Approaches to Emerging Mental Ill-Health in Young People; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; ISBN 9780367250645. [Google Scholar]

- ROMA. Available online: https://www.comune.roma.it/web/it/roma-statistica-servizi-sociali1.page (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Singh, S.P.; Anderson, B.; Liabo, K.; Ganeshamoorthy, T.; Guideline Committee. Supporting young people in their transition to adults’ services: Summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2016, 353, i2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckmann, D.; Lowman, K.L.; Nargiso, J.; McKowen, J.; Watt, L.; Yule, A.M. Substance-induced Psychosis in Youth. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 29, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winnicott, D.W. The Use of the Word “Use”. In The Collected Works of D.W. Winnicott, Volume 8, 1967–1968; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 9780190271404. [Google Scholar]

- Blos, P. The second individuation process of adolescence. Psychoanal. Study Child. 1967, 22, 162–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arain, M.; Haque, M.; Johal, L.; Mathur, P.; Nel, W.; Rais, A.; Sandhu, R.; Sharma, S. Maturation of the adolescent brain. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2013, 9, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giedd, J.N. The amazing teen brain. Sci. Am. 2015, 312, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deleuze, G. La soggettivazione. In Corso su Michel Foucault (1985–1986); Ombre Corte: Verona, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cahn, R.; Gutton, P.; Robert, P.; Tisseron, S. L’ado Et son psy, Nouvelles Approches Thérapeutiques en Psychanalyse; Editions In Press; Société psychanalytique de Paris: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Blos, P. On Adolescence: A Psychoanalytic Interpretation; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, K.; Muller Neff, D.; Pitman, S. Burnout in mental health professionals: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and determinants. Eur. Psychiatry 2018, 53, 74–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forstag, E.H.; Cuff, P.A. (Eds.) National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Global Health; Global Forum on Innovation in Health Professional Education; A Design Thinking, Systems Approach to Well-Being Within Education and Practice: Proceedings of a Workshop; Appendix, B; The Importance of Well-Being in the Health Care Workforce; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK540859/ (accessed on 11 October 2018).

- Bodenheimer, T.; Sinsky, C. From triple to quadruple aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann. Fam. Med. 2014, 12, 573–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, J.; Herkes, J.; Ludlow, K.; Testa, L.; Lamprell, G. Association between organisational and workplace cultures, and patient outcomes: Systematic review. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e017708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Revuelta, M.; Pelayo-Terán, J.M.; Juncal-Ruiz, M.; Vázquez-Bourgon, J.; Suárez-Pinilla, P.; Romero-Jiménez, R.; Setién Suero, E.; Ayesa-Arriola, R.; Crespo-Facorro, B. Antipsychotic Treatment Effectiveness in First Episode of Psychosis: PAFIP 3-Year Follow-Up Randomized Clinical Trials Comparing Haloperidol, Olanzapine, Risperidone, Aripiprazole, Quetiapine, and Ziprasidone. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020, 23, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherrill, J.; Amy, B.; Susan, G.; Azrin, T. Evidence-Based Treatments for First Episode Psychosis: Components of Coordinated Specialty Care. NIMH. Available online: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/sites/default/files/documents/health/topics/schizophrenia/raise/nimh-white-paper-csc-for-fep.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Robinson, D.G.; Schooler, N.R.; Correll, C.U.; John, M.; Kurian, B.T.; Marcy, P.; Miller, A.L.; Pipes, R.; Trivedi, M.H.; Kane, J.M. Psychopharmacological Treatment in the RAISE-ETP Study: Outcomes of a Manual and Computer Decision Support System Based Intervention. Am. J. Psychiatry 2018, 175, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haram, A.; Fosse, R.; Jonsbu, E.; Hole, T. Impact of Psychotherapy in Psychosis: A Retrospective Case Control Study. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusar-Poli, P.; Papanastasiou, E.; Stahl, D.; Rocchetti, M.; Carpenter, W.; Shergill, S.; McGuire, P. Treatments of Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia: Meta-Analysis of 168 Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trials. Schizophr. Bull. 2015, 41, 892–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skelton, M.; Khokhar, W.A.; Thacker, S.P. Treatments for delusional disorder. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 5, CD009785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gergov, V.; Milic, B.; Löffler-Stastka, H.; Ulberg, R.; Vousoura, E.; Poulsen, S. Psychological Interventions for Young People With Psychotic Disorders: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 859042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodyer, I.M.; Reynolds, S.; Barrett, B.; Byford, S.; Dubicka, B.; Hill, J.; Holland, F.; Kelvin, R.; Midgley, N.; Roberts, C.; et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy and short-term psychoanalytical psychotherapy versus a brief psychosocial intervention in adolescents with unipolar major depressive disorder (IMPACT): A multicentre, pragmatic, observer-blind, randomised controlled superiority trial. Lancet Psychiatry 2017, 4, 109–119, Erratum in Lancet Psychiatry 2017, 4, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemirovski Edlund, J.; Carlberg, G. Psychodynamic psychotherapy with adolescents and young adults: Outcome in routine practice. Clin. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2016, 21, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerber, A.J.; Fonagy, P.; Bateman, A.; Higgitt, A. Structural and symptomatic change in psychoanalysis and psychodynamic psychotherapy of young adults: A quantitative study of process and outcome. J. Am. Psychoanal. Assoc. 2004, 52, 1235–1236. [Google Scholar]

- Škodlar, B.; Henriksen, M.G.; Sass, L.A.; Nelson, B.; Parnas, J. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Schizophrenia: A Critical Evaluation of Its Theoretical Framework from a Clinical-Phenomenological Perspective. Psychopathology 2013, 46, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysaker, P.H.; Lysaker, J.T. Schizophrenia and alterations in self-experience: A comparison of 6 perspectives. Schizophr. Bull. 2010, 36, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendall, S.; Allott, K.; Jovev, M.; Marois, M.J.; Killackey, E.J.; Gleeson, J.F.; Alvarez-Jimenez, M.; McGorry, P.D.; Jackson, H.J. Therapy contamination as a measure of therapist treatment adherence in a trial of cognitive behaviour therapy versus befriending for psychosis. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2015, 43, 314–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelo, K.; Monni, S.; Tomassi, F. Le Mappe Della Disuguaglianza. Una Geografia Sociale Metropolitana; Collana: Saggine, 323; Donzelli Editore: Rome, Italy, 2019; p. XVIII-206. ISBN 9788868439880. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, S.; Mustafa, S.; Gariépy, G.; Shah, J.; Joober, R.; Lepage, M.; Malla, A. A NEET distinction: Youths not in employment, education or training follow different pathways to illness and care in psychosis. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2018, 53, 1401–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenheck, R.; Mueser, K.T.; Sint, K.; Lin, H.; Lynde, D.W.; Glynn, S.M.; Robinson, D.G.; Schooler, N.R.; Marcy, P.; Mohamed, S.; et al. Supported employment and education in comprehensive, integrated care for first episode psychosis: Effects on work, school, and disability income. Schizophr. Res. 2017, 182, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fancourt, D.; Finn, S. What Is the Evidence on the Role of the Arts in Improving Health and Well-Being? A Scoping Review; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Winnicott, D.W. Playing and Reality; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1971; ISBN 0-415-03689-5. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, R. The Golden Fleece; Il vello d’oro, Trad; Di Francesca Antonini, Corbaccio: Milano, Italy, 1993; TEA: Milano, Italy, 1997; Longanesi: Milano, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lega, I.; Pelletier, J.-F.; Caroppo, E. Editorial: Long term psychiatric care and COVID-19. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 979360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Zhai, J.; Liu, Z.; Fang, M.; Wang, B.; Wang, C.; Hu, B.; Sun, X.; Lv, L.; Lu, Z.; et al. Effect of antipsychotic medication alone vs combined with psychosocial intervention on outcomes of early-stage schizophrenia: A randomized, 1-year study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2010, 67, 895–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guénoun, T.; Attigui, P. The therapeutic group in adolescence: A process of intersubjectivation. Int. J. Psychoanal. 2021, 102, 519–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarobe, L.; Bungay, H. The role of arts activities in developing resilience and mental wellbeing in children and young people a rapid review of the literature. Perspect. Public Health 2017, 137, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arts and Health: Supporting the Well-Being of Forcibly Displaced People. Available online: https://bci-hub.org/documents/arts-and-health-supporting-well-being-forcibly-displaced-people (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Workshop for the Experts of the EU Member States on Culture for Social Cohesion. Outcomes and Lessons Learned, EC Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture-Unit for Cultural Policy. Report-Workshop for EU Experts on Culture for Social Cohesion|Culture and Creativity. Available online: https://culture.ec.europa.eu/document/report-workshop-for-eu-experts-on-culture-for-social-cohesion (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Suicide Increasing Amongst Europe’s Youth, Governments Underprepared. Available online: https://www.euractiv.com/section/coronavirus/news/suicide-increasing-amongst-europes-youth-governments-underprepared/ (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Winter, R.; Lavis, A. The Impact of COVID-19 on Young People’s Mental Health in the UK: Key Insights from Social Media Using Online Ethnography. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinlay, A.R.; May, T.; Dawes, J.; Fancourt, D.; Burton, A. “You’re just there, alone in your room with your thoughts” A qualitative study about the impact of lockdown among young people during the COVID-19 pandemic. medRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Referrals from TSMREE | CSM | TSMREE/CSM | Referrals to Other Services | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic Group | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

| Schizophrenia spectrum disorders | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Affective psychosis | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Severe personality disorders | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Common mental disorders | 10 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Other disorders | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| No psychiatric disorder | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unknown diagnosis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 21 | 13 | 12 | 21 | 6 | 8 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| % | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 46.2 | 66.7 | 0 | 30.7 | 8.3 | 0 | 23.1 | 25 |

| Mean age | 19 | 18.7 | 18.4 | |||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grasso, M.; Giammetta, R.; Gabriele, G.; Mazza, M.; Caroppo, E. A Treatment Model for Young Adults with Severe Mental Disorders in a Community Mental Health Center: The Crisalide Project and the Potential Space. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15252. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215252

Grasso M, Giammetta R, Gabriele G, Mazza M, Caroppo E. A Treatment Model for Young Adults with Severe Mental Disorders in a Community Mental Health Center: The Crisalide Project and the Potential Space. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(22):15252. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215252

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrasso, Maria, Rosalia Giammetta, Giuseppina Gabriele, Marianna Mazza, and Emanuele Caroppo. 2022. "A Treatment Model for Young Adults with Severe Mental Disorders in a Community Mental Health Center: The Crisalide Project and the Potential Space" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 22: 15252. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215252

APA StyleGrasso, M., Giammetta, R., Gabriele, G., Mazza, M., & Caroppo, E. (2022). A Treatment Model for Young Adults with Severe Mental Disorders in a Community Mental Health Center: The Crisalide Project and the Potential Space. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 15252. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215252