Older Black Lesbians’ Needs and Expectations in Relation to Long-Term Care Facility Use

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Researcher Reflexivity

2.2. Data

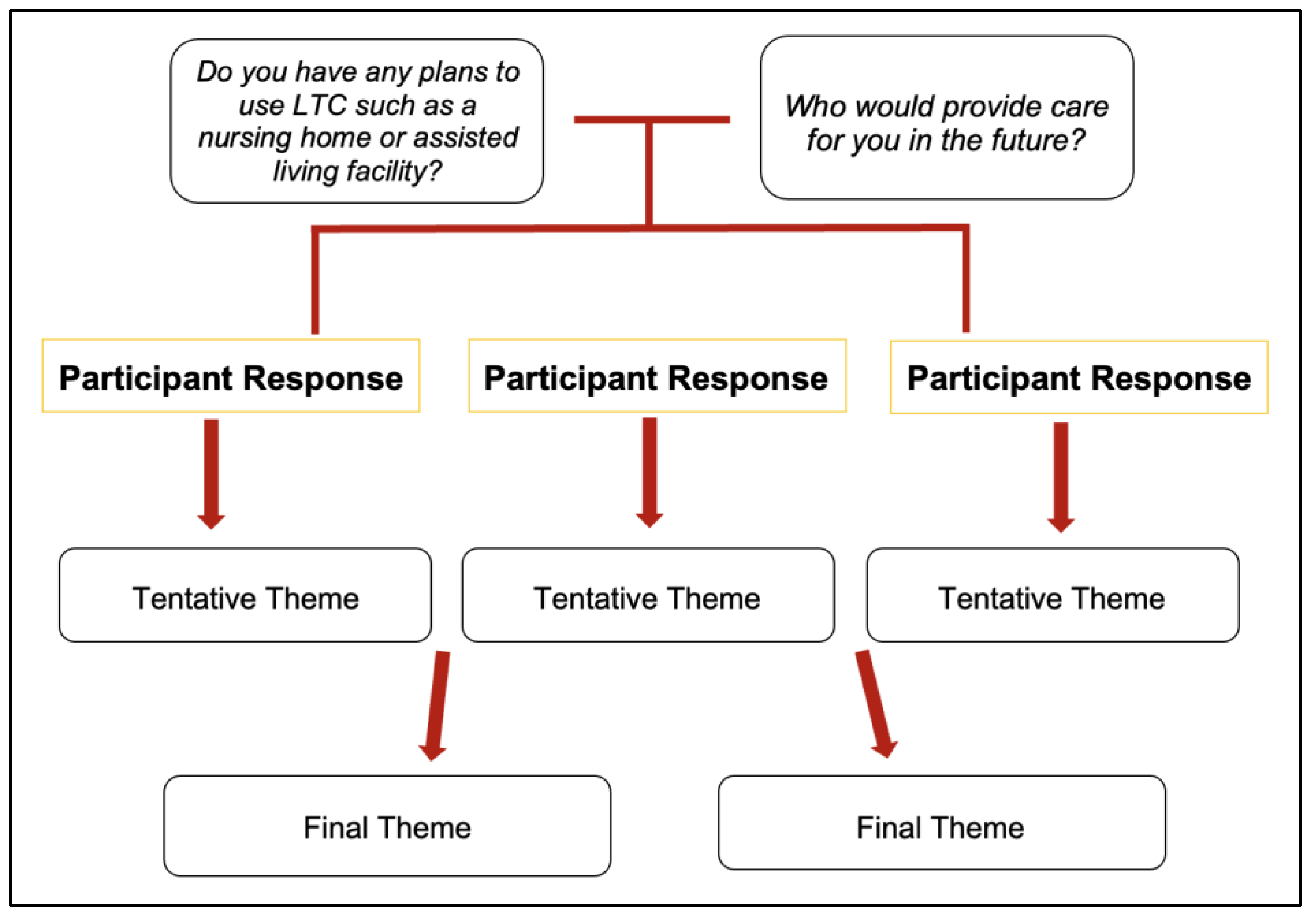

2.3. Study Design and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Consideration or Plans to Utilize Long-Term Care (LTC)

“Basically, most of my family is gone, so I would stay in a nursing home”(Person 1, Group 10).

“I don’t know. I think I would have to do an assisted living type of facility”(Person 4, Group 13).

“I guess I’ll be in somebody’s home some kinda way somewhere. I don’t know”(Person, 6, Group 6).

“Well, I have children and grandchildren. But my grandchildren, they’ve already informed me that although they love me, they will try to make enough money to put me somewhere for somebody to see after me. They’ve already told me”(Person 7, Group 10).

“I have to agree with [participant]. I have no children [or a] partner. And that does weigh on me at my age right now, as to what would be my next step…I have brothers. I have nieces, but it’s not anything that I’m gonna try to expect from them or the children. It’s just something that I’m trying to mentally grasp, what is that next step. It’s troubling because you just don’t know”(Person 2, Group 13).

“I wouldn’t trust anyone in my family to take care of me. So, it would definitely be a nursing home. That about sums it up”(Person 9, Group 10).

“I thought about growing old and not being able to care sufficiently for myself. I have both a long-term care insurance plan that I think is comprehensive and should serve me well when that time comes if I can’t continue to afford to pay for it”(Person 1, Group 14).

“I’ve tried to plan financially like to have good insurance to go to a nursing home or something like that”(Person 2, Group 5).

“I’ve got to get some long-term care insurance and put some things in place for me”.—Person 7, Group 5

3.2. Concern for the Facility Environment

“So, I think that that would kill me, sort of softly kill me to have to live in a situation where all of a sudden, couldn’t be authentically who I was. I think it’s more real than we realize ‘cause not that many people are disclosing because there’s a trust issue and they don’t know who they’re telling and who you’re gonna tell. I think we probably encounter people all the time that are choosing to live in the closet for survival and we just don’t even know it”(Person 8, Group 5).

“But even if I did sell my home and move into a facility, would they be lesbian sensitive? That really bothers me. I don’t want to have to at this age, kinda of suppress that. So that makes me gravitate toward staying in my home and do what I wanna do”(Person 11, Group 1).

“From what I’ve seen of nursing homes and assisted living, it’s just horrible. It’s this loss of independence first and foremost and just loss of everything that you have worked your whole life to build… and I’m not just talking about your possessions, but who you are. So, I just cannot imagine. I’ve read a lot about LGB folks going into facilities and basically losing who they are, losing their life and their identity and that’s a scary thing. It’s a scary thing first of all going into assisted living or a nursing home for me, just the thought of it, and then on top of that, to lose myself”(Person 10, Group 5).

“I just want to address the whole thing about nursing homes. I don’t know if it’s so much the character of the people who work there, although of course that’s a part of it, it’s the resources that we give to facilities like nursing homes. They’re just not adequate. I remember working at one as a nurse. I don’t know if I was a nurse or an aid, but I remember they gave me like twenty-something patients and I’m like what the hell am I supposed to do. So even if you have an LGBT nursing home, without adequate resources you’re still not gonna have adequate care. So that I think has gotta be addressed on a systemic level, is how are we treating our elders and if you’re lucky, we’ll all be old one day(Person 11, Group 14).

3.3. Building A Community of Mutual Support

“I’ve been researching lesbian homes or lesbian community… and there aren’t any in the U.S. I’ve been trying to get with some of my real estate investor friends and things like that, my older friends and say, “Look, what are you doing? What are we doing? You have property over here…. let’s combine those efforts and see if we can create a community. So that’s my effort for myself, is to whatever it is I like, I wanna create it. So, I want to get those people involved so I’m not taking care of her, she’s not taking care of me, but we’re supporting each other on some sort of mutually invested interests. And then I’m assured to be around those people that I’ve cared [for] and cultivated a relationship with. So that’s what I’m doing right now. I’m building that sort of community”(Person 4, Group 6).

“I think intentional communities. I have a lot of friends. We’re talking about starting an intentional community which I also think will help with growing older together and supporting one another that way as well. I think that’s really important. Everyone’s not going to have partners to take care of them. Everyone’s not going to have children to take care of them”(Person 8, Group 1).

“I think the loneliness and isolation piece is very relevant to this topic because as lesbians age, many lesbians don’t have children. Many have been ex-communicated from their family of origin…so the fact of the matter is, the thought of aging and being without family or without community, it’s a very real topic. We talk about building community and I think that’s really critical. I have one of my very good friends, she doesn’t have any family [or] children. I’m concerned about her aging and being alone. I would take her into her house and take care of her if I needed to, but I have a partner, so how does that really work out?”(Person 3, Group 8).

“I’m single without a partner. So, I have two best friends. We had this conversation a couple of times about us living in community and trying to take care of one another”(Person 6, Group 10).

“Hopefully my community. I’m a part of a Yoruba community, Santeria community, and family member, nieces and nephews. I don’t have a partner and I’m not looking for a partner so it would be my community”(Person 3, Group 12).

“My partner, children, lifelines. I’m building community now. You have to build community. You wanna believe that everyone’s gonna be on board or even around. You make assumptions that people will be there to take care of you and what if they’re not there, or what if they’re unable to. So, you might need to build community to corral not just for yourself but for each other”(Person 5, Group 12).

“I have strong family relationships with my sisters’ children, my nieces. I think they would care for me, but in addition to all that, my partner and I have started dialogue with friends who are of various ages where we are thinking more about caring for each other and being each other’s support. I feel pretty confident about getting older”(Person 6, Group 14).

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- LGBT Demographic Data Interactive. Available online: https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/visualization/lgbt-stats/?topic=LGBT&characteristic=african-american#density (accessed on 1 January 2019).

- Singleton, M.; García, C.; Brown, L. “How Much Time Do You Want for Your ‘Progress’?” Inequitable Aging for Diverse Sexual and Gender Minorities. 2021. Available online: https://generations.asaging.org/unfair-aging-sexual-and-gender-minorities (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Jones, J. LGBT Identification in U.S. Ticks Up to 7.1%. 2022. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/poll/389792/lgbt-identification-ticks-up.aspx (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Chen, J.; McLaren, H.; Jones, M.; Shams, L. The Aging Experiences of LGBTQ Ethnic Minority Elders: A Systematic Review. Gerontologist 2020, 62, e162–e177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houghton, A. Maintaining Dignity: Understanding and Responding to the Challenges Facing Older LGBT Americans. AARP Res. 2018. Available online: https://doi.org/https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/surveys_statistics/life-leisure/2018/maintaining-dignity-lgbt.doi.10.26419%252Fres.00217.001.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2018).

- Fredriksen-Goldsen, K.; Kim, H.; Emlet, C.; Muraco, A.; Erosheva, E.; Hoy-Ellis, C.; Goldsen, J.; Petry, H. The Aging and Health Report: Disparities and Resilience among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Older Adults; Institute for Multigenerational Health: Seattle, WA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre, S.L.; Antonucci, E.A.; Haden, S.C. Being White Helps: Intersections of Self-Concealment, Stigmatization, Identity Formation, and Psychological Distress in Racial and Sexual Minority Women. J. Lesbian Stud. 2014, 18, 158–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.-C.; Matthews, A.K.; Aranda, F.; Patel, C.; Patel, M. Predictors and consequences of negative patient-provider interactions among a sample of African American sexual minority women. LGBT Health 2015, 2, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Sluytman, L.G.; Torres, D. Hidden or uninvited? A content analysis of elder LGBT of color literature in gerontology. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2014, 57, 130–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woody, I. Aging out: A qualitative exploration of ageism and heterosexism among aging African American lesbians and gay men. J. Homosex. 2014, 61, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woody, I. Lift every voice: Voices of African-American lesbian elders. J. Lesbian Stud. 2015, 19, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, F.; Hill, M.J.; Kellam, C. Black Lesbians Matter. 2010. Available online: www.zunainstitute.org (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Scharp, K.M.; Thomas, L.J. Disrupting the humanities and social science binary: Framing communication studies as a transformative discipline. Rev. Commun. 2019, 19, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seelman, K.L.; Adams, M.A.; Poteat, T. Interventions for healthy aging among mature Black lesbians: Recommendations gathered through community-based research. J. Women Aging 2017, 29, 530–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 2nd ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dickson, L.; Bunting, S.; Nanna, A.; Taylor, M.; Spencer, M.; Hein, L. Older Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Adults’ Experiences with Discrimination and Impacts on Expectations for Long-Term Care: Results of a Survey in the Southern United States. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2021, 41, 650–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasullo, K.; McIntosh, E.; Buchholz, S.W.; Ruppar, T.; Ailey, S. LGBTQ Older Adults in Long-Term Care Settings: An Integrative Review to Inform Best Practices. Clin. Gerontol. 2021, 45, 1087–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, C.; Diaz, M.; Wagner, L.M. Long-Term Services and Supports Policy Issues. In Policy & Politics in Nursing and Health Care-E-Book; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; p. 296. [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg, L.; Huang, J.; Brooks, K.; Black, A.; Burkholder, G. Triple jeopardy and beyond: Multiple minority stress and resilience among black lesbians. J. Lesbian Stud. 2003, 7, 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knochel, K.A.; Flunker, D. Long-Term Care Expectations and Plans of Transgender and Nonbinary Older Adults. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2021, 40, 1542–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelts, M.D.; Galambos, C. Intergroup Contact: Using Storytelling to Increase Awareness of Lesbian and Gay Older Adults in Long-Term Care Settings. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2017, 60, 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, G.L.; Beckerman, N.L.; Sherman, P.A. Lesbian and gay elders and long-term care: Identifying the unique psychosocial perspectives and challenges. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2010, 53, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, M.; Gassoumis, Z.D.; Enguidanos, S. Anticipated Need for Future Nursing Home Placement by Sexual Orientation: Early Findings from the Health and Retirement Study. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2021, 19, 656–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurd, L.; Mahal, R.; Wardell, V.; Liang, J. “There were no words”: Older LGBTQ+ persons’ experiences of finding and claiming their gender and sexual identities. J. Aging Stud. 2022, 60, 100999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andel, S.A.; Tedone, A.M.; Shen, W.; Arvan, M.L. Safety implications of different forms of understaffing among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasater, K.B.; Aiken, L.H.; Sloane, D.M.; French, R.; Martin, B.; Reneau, K.; Alexander, M.; McHugh, M.D. Chronic hospital nurse understaffing meets COVID-19: An observational study. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2021, 30, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, J.B.; Putney, J.M.; Shepard, B.L.; Sass, S.E.; Rudicel, S.; Ladd, H.; Cahill, S. Healthy Aging in Community for Older Lesbians. LGBT Health 2016, 3, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Battle, J.; DeFreece, A. The Impact of Community Involvement, Religion, and Spirituality on Happiness and Health among a National Sample of Black Lesbians. Women Gend. Fam. Color 2014, 2, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowleg, L.; Burkholder, G.; Teti, M.; Craig, M.L. The Complexities of Outness: Psychosocial Predictors of Coming Out to Others Among Black Lesbian and Bisexual Women. J. LGBT Health Res. 2008, 4, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S. Black on Black Love: Black Lesbian and Bisexual Women, Marriage, and Symbolic Meaning. Black Sch. 2017, 47, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N = 100 | |

|---|---|

| Age * | 54 |

| Ethnicity | |

| African American | 95.0 |

| Caribbean/West Indian | 6.0 |

| Hispanic | 2.0 |

| Bi-Racial/Multi-racial | 7.0 |

| Other | 2.0 |

| Sexual Identity | |

| Lesbian | 81.0 |

| Bisexual | 3.0 |

| Gay | 8.0 |

| Same Gender Loving | 14.0 |

| Other | 2.0 |

| Education Level | |

| Some High School | 2.0 |

| High School Graduate/GED | 14.0 |

| Some College | 30.0 |

| College Graduate | 29.0 |

| Graduate/Professional Degree | 24.0 |

| Religion | |

| Protestant | 61.0 |

| Catholic | 2.0 |

| Muslim | 1.0 |

| Buddhist | 4.0 |

| Other | 23.0 |

| Relationship Status | |

| Single | 43.0 |

| Partnered | 51.0 |

| Other | 6.0 |

| Marital Status | |

| Legally married to man | 3.0 |

| Legally married to woman | 10.0 |

| Civil union with man | 0.0 |

| Civil union with woman | 8.0 |

| Registered domestic partnership | 6.0 |

| Common-law marriage | 0.0 |

| Legal separation | 2.0 |

| Divorced | 18.0 |

| Never married | 38.0 |

| Other | 14.0 |

| Household Members | |

| Self | 31.0 |

| Self and spouse | 3.0 |

| Self and partner | 27.0 |

| Self, spouse/partner, and family members | 14.0 |

| Self and family members | 18.0 |

| Roommate | 6.0 |

| Occupation | |

| Unemployed | 29.0 |

| Employed | 58.0 |

| Self-employed | 4.0 |

| Retired | 7.0 |

| Health Insurance | |

| Uninsured | 20.0 |

| Insured w/private | 37.0 |

| Insured w/government | 17.0 |

| Insured w/Medicare and/or Medicaid | 27.0 |

| Household Income | |

| <$10,000 | 13.0 |

| $10,001 to $30,000 | 23.0 |

| $30,001 to $60,000 | 39.0 |

| $60,001 to $100,000 | 16.0 |

| >$100,000 | 5.0 |

| Health Rating | |

| Poor | 1.0 |

| Fair | 20.0 |

| Good | 50.0 |

| Very Good | 1.0 |

| Excellent | 2.0 |

| Other | 23.0 |

| Disability | |

| No | 57.0 |

| Yes | 36.0 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Singleton, M.; Adams, M.A.; Poteat, T. Older Black Lesbians’ Needs and Expectations in Relation to Long-Term Care Facility Use. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15336. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215336

Singleton M, Adams MA, Poteat T. Older Black Lesbians’ Needs and Expectations in Relation to Long-Term Care Facility Use. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(22):15336. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215336

Chicago/Turabian StyleSingleton, Mekiayla, Mary Anne Adams, and Tonia Poteat. 2022. "Older Black Lesbians’ Needs and Expectations in Relation to Long-Term Care Facility Use" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 22: 15336. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215336