Migration-Related Weight Changes among African Immigrants in the United States

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Participants

- Design

- Outcome of interest

- Exposures

- Covariates

- Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

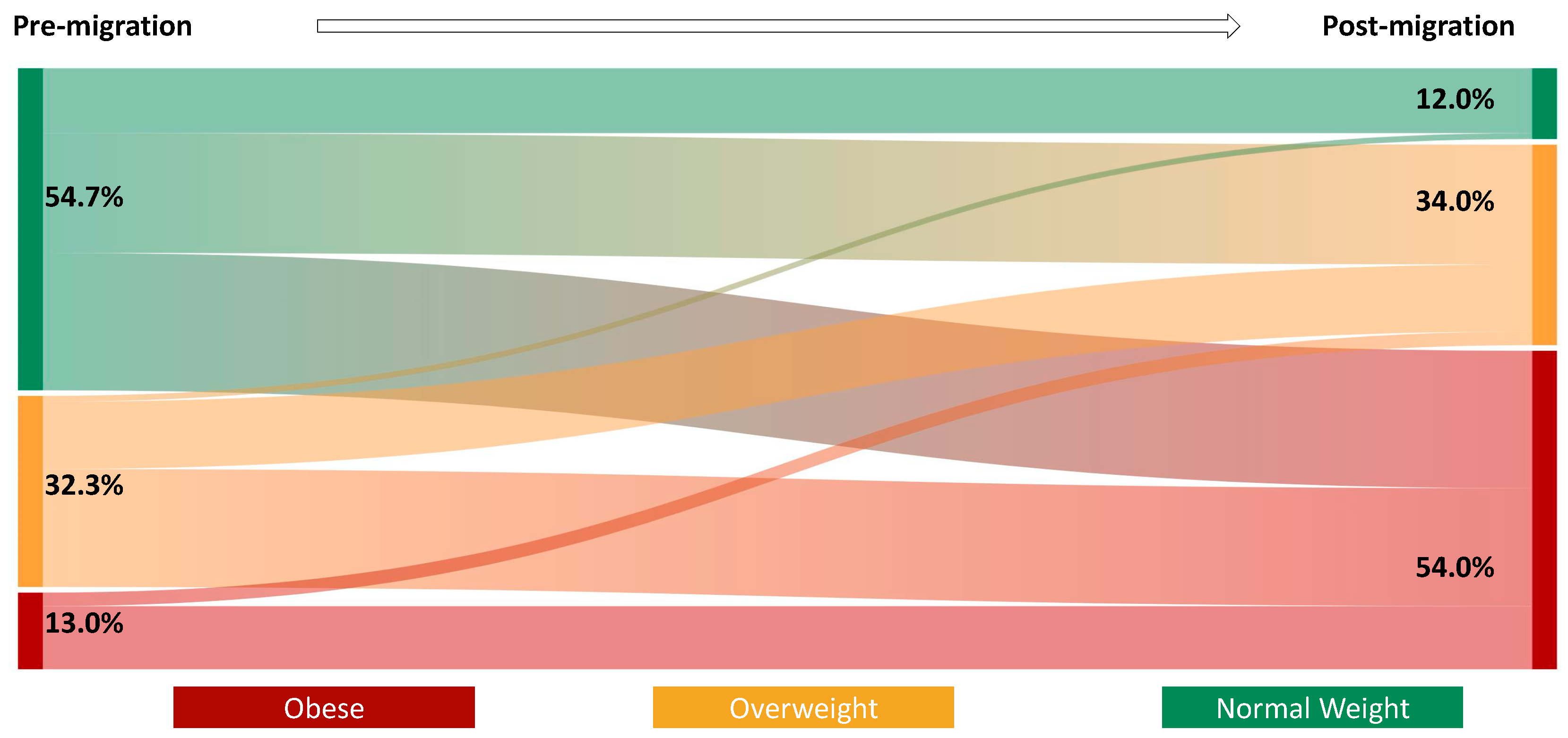

3.2. BMI, BMI Category, and Weight Changes Post Migration

3.3. Factors Associated with BMI Category Changes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cawley, J.; Biener, A.; Meyerhoefer, C.; Ding, Y.; Zvenyach, T.; Gabriel Smolarz, N.B. Ramasamy A Direct medical costs of obesity in the United States and the most populous states. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2021, 27, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Poirier, P.; Giles, T.D.; Bray, G.A.; Hong, Y.; Stern, J.S.; Pi-Sunyer, F.X. Eckel RH Obesity and cardiovascular disease: Pathophysiology, evaluation, and effect of weight loss: An update of the 1997 American Heart Association Scientific Statement on Obesity and Heart Disease from the Obesity Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circulation 2006, 113, 898–918. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hales, C.M.; Carroll, M.D.; Fryar, C.D.; Ogden, C.L. Prevalence of Obesity and Severe Obesity among Adults: United States, 2017–2018 Key findings Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; NCHS Data Brief; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Agyemang, C.; Meeks, K.; Beune, E.; Owusu-Dabo, E.; Mockenhaupt, F.P.; Addo, J.; de Graft Aikins, A.; Bahendeka, S.; Danquah, I.; Schulze, M.B.; et al. Obesity and type 2 diabetes in sub-Saharan Africans—Is the burden in today’s Africa similar to African migrants in Europe? The RODAM study. BMC Med. 2016, 14, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Commodore-Mensah, Y.; Samuel, L.J.; Dennison-Himmelfarb, C.R.; Agyemang, C. Hypertension and overweight/obesity in Ghanaians and Nigerians living inWest Africa and industrialized countries: A systematic review. J. Hypertens. 2014, 32, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrazas, A. Article: African Immigrants in the United States i..|Migrationpolicy.org. 2009. Available online: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/african-immigrants-united-states-2007 (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Echeverria-Estrad, C.; Batalova, J. Article 2019, Sub-Saharan African Immigrants in th.|Migrationpolicy.org. 2019. Available online: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/sub-saharan-african-immigrants-united-states-2018 (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Institute of Medicine (US) Subcommittee on Military Weight Management. 3, Factors That Influence Body Weight. In Weight Management: State of the Science and Opportunities for Military Programs; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2004. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK221834/ (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Murphy, M.; Robertson, W.; Oyebode, O. Obesity in International Migrant Populations. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2017, 6, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheung, B.Y.; Chudek, M.; Heine, S.J. Evidence for a Sensitive Period for Acculturation. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 22, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Commodore-Mensah, Y.; Turkson-Ocran, R.A.; Nmezi, N.A.; Nkimbeng, M.; Cudjoe, J.; Mensah, D.S.; York, S.; Mossburg, S.; Patel, N.; Adu, E. Commentary: Engaging African immigrants in research–Experiences and lessons from the field. Ethn. Dis. 2019, 29, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrow, J.S.; Webster, J. Quetelet’s index (W/H2) as a measure of fatness. Int. J. Obes. 1985, 9, 147–153. [Google Scholar]

- Golubnitschaja, O.; Liskova, A.; Koklesova, L.; Samec, M.; Biringer, K.; Büsselberg, D.; Podbielska, H.; Kunin, A.A.; Evsevyeva, M.E.; Shapira, N. Caution, “normal” BMI: Health risks associated with potentially masked individual underweight—EPMA Position Paper 2021. EPMA J. 2021, 12, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, X.; Monclús, E.; Escoda, O.; Guerra-García, M.; Moreno, P.; Guasch, N.; López-Soto, A. Unintentional weight loss: Clinical characteristics and outcomes in a prospective cohort of 2677 patients. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lorem, G.F.; Schirmer, H.; Emaus, N. What is the impact of underweight on self-reported health trajectories and mortality rates: A cohort study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2017, 15, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immigrant Acculturation, Gender and Health Behavior: A Research Note on JSTOR. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3598318#metadata_info_tab_contents (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- Himmelgreen, D.A.; Pérez-Escamilla, R.; Martinez, D.; Bretnall, A.; Eells, B.; Peng, Y.; Bermúdez, A. The longer you stay, the bigger you get: Length of time and language use in the U.S. are associated with obesity in Puerto Rican women. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2004, 125, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delavari, M.; Sønderlund, A.L.; Swinburn, B.; Mellor, D.; Renzaho, A. Acculturation and obesity among migrant populations in high income countries—A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Goel, M.S.; McCarthy, E.P.; Phillips, R.S.; Wee, C.C. Obesity Among US Immigrant Subgroups by Duration of Residence. JAMA 2004, 292, 2860–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, D.; Ogungbe, O.; Turkson-Ocran, R.-A.N.; Onuoha, C.; Byiringiro, S.; Nmezi, N.A.; Mannoh, I.; Wecker, E.; Madu, E.N.; Commodore-Mensah, Y. The Cardiometabolic Health of African Immigrants in High-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gona, C.M.; Lupafya, T.H.; Zhou-Chidavaenzi, N.; Mafundikwa, E.; Gona, P.N. The Health Status of Zimbabwean Immigrants in the US: A Needs Assessment. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2021, 30, 969–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njeru, J.W.; Wieland, M.L.; Okamoto, J.M.; Novotny, P.J.; Breen-Lyles, M.K.; Osman, A.; Ahmed, Y.A.; Nur, M.A.; Nur, O.; Sia, I.G. Social networks and obesity among Somali immigrants and refugees. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjei, D.N.; Stronks, K.; Adu, D.; Beune, E.; Meeks, K.; Smeeth, L.; Addo, J.; Owuso-Dabo, E.; Klipstein-Grobusch, K.; Mockenhaupt, F.P.; et al. Chronic kidney disease burden among African migrants in three European countries and in urban and rural Ghana: The RODAM cross-sectional study. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2018, 33, 1812–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deforche, B.; van Dyck, D.; Deliens, T.; de Bourdeaudhuij, I. Changes in weight, physical activity, sedentary behaviour and dietary intake during the transition to higher education: A prospective study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deng, Y.; Hwang, Y.; Campbell, S.; McCullick, B.A.; Yli-Piipari, S. Institutional factors associated with college students’ healthy physical activity and body composition: A first semester follow-up. J. Am. Coll. Health 2021, 71, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröger, H.; Leopold, L. Education differences in women’s body weight trajectories: The role of motherhood. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devaux, M.; Sassi, F.; Church, J.; Cecchini, M.; Borgonovi, F. Exploring the Relationship Between Education and Obesity. OECD J. Econ. Studies. 2011, 1, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Winkleby, M.A.; Jatulis, D.E.; Frank, E.; Fortmann, S.P. Socioeconomic status and health: How education, income, and occupation contribute to risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 82, 816–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Berry, J.W. Acculturation. In Handbook of Socialization: Theory and Research, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 520–538. [Google Scholar]

- Miller De Rutté, A.M.; Rubenstein, B.P. Acculturative Stress and the Effects on Health and Health Behaviors in Hispanic Immigrants: A Systematic Review. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2021, 43, 433–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshahat, S.; Moffat, T.; Newbold, K.B. Understanding the Healthy Immigrant Effect in the Context of Mental Health Challenges: A Systematic Critical Review. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2021, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toselli, S.; Gualdi-Russo, E.; Boulos, D.N.K.; Anwar, W.A.; Lakhoua, C.; Jaouadi, I.; Khyatti, M.; Hemminki, K. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in adults from North Africa. Eur. J. Public Health 2014, 24 (Suppl. S1), 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lindberg, N.M.; Stevens, V.J. Immigration and Weight Gain: Mexican-American Women’s Perspectives. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2009, 13, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Obesity Update-OECD. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/health/obesity-update.htm (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- Lee, A.; Cardel, M.; Donahoo, W.T. Social and Environmental Factors Influencing Obesity; MDText.com, Inc.: South Dartmouth, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.A.; Dhanasekaran, D.; Ganamurali, N.L.P.; Sabarathinam, S. Junk food-induced obesity-a growing threat to youngsters during the pandemic. Obes Med. 2021, 26, 100364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, L.D.; Andresen, M.A.; Schmid, T.L. Obesity relationships with community design, physical activity, and time spent in cars. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2004, 27, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haregu, T.N.; Mohamed, S.F.; Muthuri, S.; Khayeka-Wandabwa, C.; Kyobutungi, C. Body mass index and wealth index: Positively correlated indicators of health and wealth inequalities in Nairobi slums. Glob. Health Epidemiol. Genom. 2018, 3, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daran, B.; Levasseur, P. Is overweight still a problem of rich in sub-Saharan Africa? Insights based on female-oriented demographic and health surveys. World Dev. Perspect 2022, 25, 100388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K.; Habash, D.L.; Fagundes, C.P.; Andridge, R.; Peng, J.; Malarkey, W.B.; Belury, M.A. Daily Stressors, Past Depression, and Metabolic Responses to High-Fat Meals: A Novel Path to Obesity. Biol. Psychiatry 2015, 77, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ahmed, S.; Rasmussen, A. Changes in Social Status and Postmigration Mental Health Among West African Immigrants. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2019, 90, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangalang, C.C.; Becerra, D.; Mitchell, F.M.; Lechuga-Peña, S.; Lopez, K.; Kim, I. Trauma, Post-Migration Stress, and Mental Health: A Comparative Analysis of Refugees and Immigrants in the United States. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2019, 21, 909–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saasa, S.K.; Rai, A.; Malazarte, N.; Yirenya-Tawiah, A.E. Mental health service utilization among African immigrants in the United States. J. Community Psychol. 2021, 49, 2144–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derr, A.S. Mental health service use among immigrants in the United States: A systematic review. Psychiatr. Serv. 2016, 67, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cox, C.E. Role of physical activity for weight loss and weight maintenance. Diabetes Spectrum. 2017, 30, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Camhi, S.M.; Bray, G.A.; Bouchard, C.; Greenway, F.L.; Johnson, W.D.; Newton, R.L.; Ravussin, E.; Ryan, D.H.; Smith, S.R.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. The Relationship of Waist Circumference and BMI to Visceral, Subcutaneous, and Total Body Fat: Sex and Race Differences. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011, 19, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Total (N = 300) | Healthy BMI Change or Maintenance N = 43 | Unhealthy BMI Maintenance N = 66 | Unhealthy BMI Change N = 191 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current age, mean (SD) | 46.89 (11.4) | 42.57 (10.7) a * | 49.44 (11.2) b | 46.97 (11.5) b | 0.009 † |

| Age at migration, mean (SD) | 33.03 (10.6) | 33.30 (9.4) a * | 40.39 (11.0) b | 30.42 (9.41) ac | 0.000 † |

| Sex | 0.119 | ||||

| Male | 132 (44.00) | 25 (58.14) | 26 (39.39) | 81 (42.41) | |

| Female | 168 (56.00) | 18 (41.86) | 40 (60.61) | 110 (57.59) | |

| Marital status | 0.833 | ||||

| Never married | 26 (8.67) | 5 (11.63) | 4 (6.06) | 17 (8.9) | |

| Married or cohabiting | 222 (74.00) | 32 (74.42) | 49 (74.24) | 141 (73.82) | |

| Separated/widowed/divorced | 53 (17.33) | 6 (13.95) | 13 (19.7) | 33 (17.28) | |

| Educational level | 0.447 | ||||

| Less than bachelor’s degree | 104 (34.78) | 14 (32.56) | 21 (31.82) | 69 (36.32) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 102 (34.11) | 18 (41.86) | 19 (28.79) | 65 (34.21) | |

| Graduate | 93 (31.10) | 11 (25.58) | 26 (39.39) | 56 (29.47) | |

| Income level | 0.360 | ||||

| <$40,000 | 52 (18.51) | 12 (28.57) | 12 (20.69) | 28 (15.47) | |

| $40,000–<$70,000 | 72 (25.62) | 8 (19.05) | 15 (25.86) | 49 (27.07) | |

| $70,000–<$100,000 | 68 (24.20) | 9 (21.43) | 10 (17.24) | 49 (27.07) | |

| ≥$100,000 | 89 (31.67) | 13 (30.95) | 21 (36.21) | 55 (30.39) | |

| Currently employed | 0.002 † | ||||

| Yes | 246 (83.39) | 7 (16.28) | 20 (30.77) | 22 (11.76) | |

| No | 49 (16.61) | 36 (83.72) | 45 (69.23) | 165 (88.24) | |

| Percentage of life in the US | 0.000 † | ||||

| <25% | 129 (43.00) | 27 (62.79) | 44 (66.67) | 58 (30.37) | |

| 25% or more | 171 (57.00) | 16 (37.21) | 22 (33.33) | 133 (69.63) | |

| Reason for migration | 0.034 † | ||||

| Education | 74 (25.96) | 5 (11.9) | 11 (17.19) | 58 (32.4) | |

| Employment/Economy | 70 (24.56) | 17 (40.48) | 15 (23.44) | 38 (21.23) | |

| Family reasons | 87 (30.53) | 13 (30.95) | 22 (34.38) | 52 (29.05) | |

| Asylum/Refugee | 21 (7.37) | 2 (4.76) | 8 (12.5) | 11 (6.15) | |

| Other reasons | 33 (11.58) | 5 (11.9) | 8 (12.5) | 20 (11.17) |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy BMI change or maintenance | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Unhealthy BMI maintenance | ||

| Age at migration, years | 1.06 (1.02, 1.10) ** | 1.07 (1.01, 1.14) * |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Female | 2.13 (0.98, 4.67) | 2.67 (1.02, 7.02) * |

| Stress level | ||

| Low (PSS < 6) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| High (PSS ≥ 6) | 2.06 (0.92, 4.64) | 1.96 (0.77, 4.99) |

| Reason for migration | ||

| Employment/Economy | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Education | 2.49 (0.70, 8.83) | 2.55 (0.61, 10.61) |

| Family reasons | 1.92 (0.72, 5.09) | 1.11 (0.34, 3.65) |

| Asylum/Refugee | 4.53 (0.83, 24.76) | 3.06 (0.43, 21.78) |

| Others | 1.81 (0.49, 6.76) | 1.29 (0.27, 6.04) |

| Percentage of life in the US | ||

| <25% | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| ≥25% | 0.84 (0.38, 1.88) | 1.16 (0.39, 3.45) |

| Unhealthy BMI change | ||

| Age at migration, years | 0.97 (0.93, 1.00) | 1.00 (0.94, 1.06) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Female | 1.88 (0.96, 3.68) | 1.75 (0.78, 3.92) |

| Stress level | ||

| Low (PSS < 6) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| High (PSS ≥ 6) | 2.13 (1.05, 4.33) * | 2.24 (1.01, 4.99) * |

| Reason for migration | ||

| Employment/Economy | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Education | 5.19 (1.76, 15.24) ** | 3.88 (1.17; 12.75) * |

| Family reasons | 1.79 (0.77, 4.12) | 1.23 (0.46, 3.24) |

| Asylum/Refugee | 2.46 (0.49, 12.32) | 2.15 (0.35, 13.03) |

| Others | 1.79 (0.57, 5.56) | 1.3 (0.36, 4.85) |

| Percentage of life in the US | ||

| <25% | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| ≥25% | 3.77 (1.89, 7.52) ** | 2.78 (1.1, 6.97) * |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Byiringiro, S.; Koirala, B.; Ajibewa, T.; Broni, E.K.; Liu, X.; Adeleye, K.; Turkson-Ocran, R.-A.N.; Baptiste, D.; Ogungbe, O.; Himmelfarb, C.D.; et al. Migration-Related Weight Changes among African Immigrants in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15501. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315501

Byiringiro S, Koirala B, Ajibewa T, Broni EK, Liu X, Adeleye K, Turkson-Ocran R-AN, Baptiste D, Ogungbe O, Himmelfarb CD, et al. Migration-Related Weight Changes among African Immigrants in the United States. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):15501. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315501

Chicago/Turabian StyleByiringiro, Samuel, Binu Koirala, Tiwaloluwa Ajibewa, Eric K. Broni, Xiaoyue Liu, Khadijat Adeleye, Ruth-Alma N. Turkson-Ocran, Diana Baptiste, Oluwabunmi Ogungbe, Cheryl Dennison Himmelfarb, and et al. 2022. "Migration-Related Weight Changes among African Immigrants in the United States" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 15501. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315501