Impact and Analysis of the Renovation Program of Dilapidated Houses in China on Poor Peasant Households’ Life Satisfaction: A Survey of 2617 Peasant Households in Gansu Province

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Renovation Program of Dilapidated Houses in China

2.1. Application and Screening

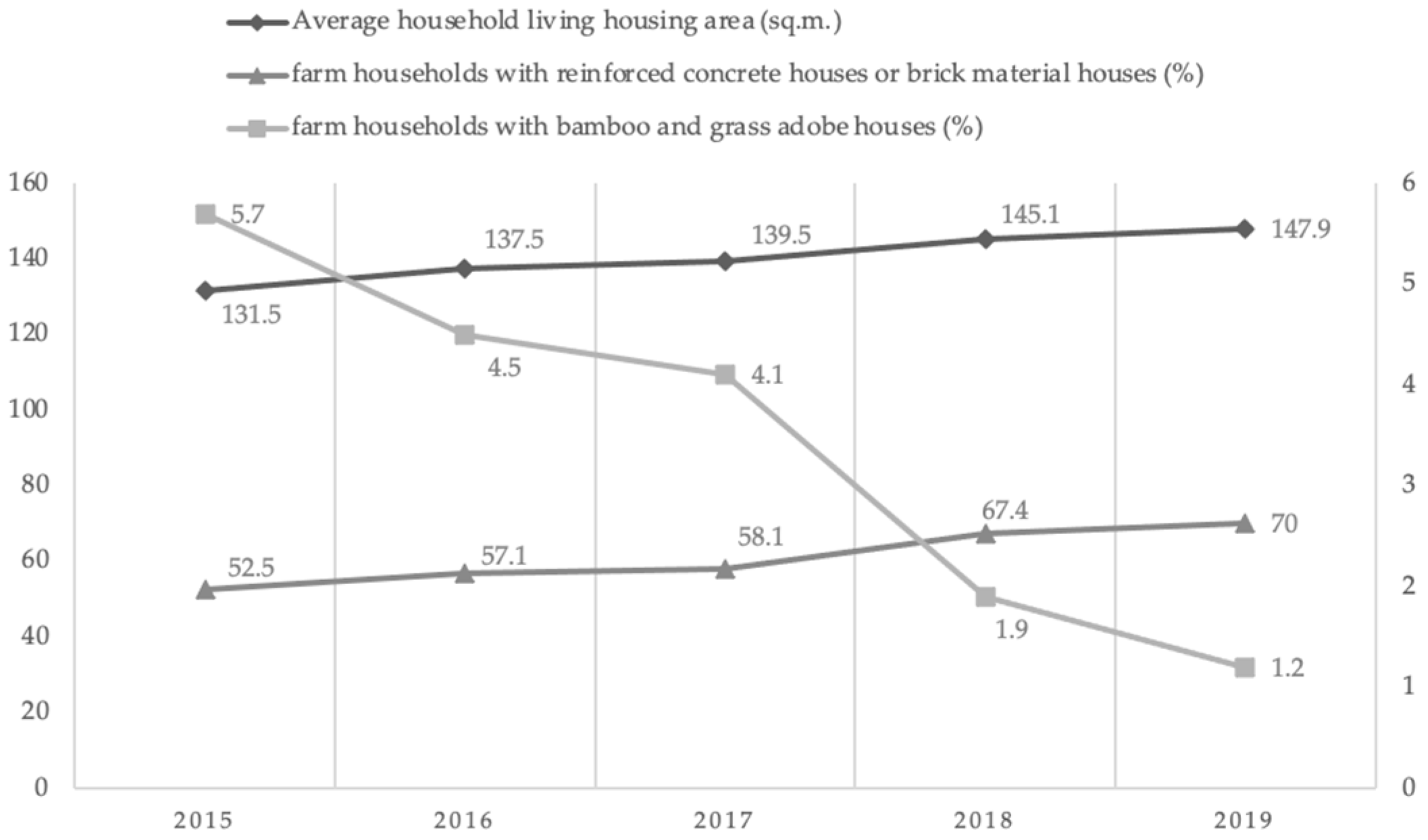

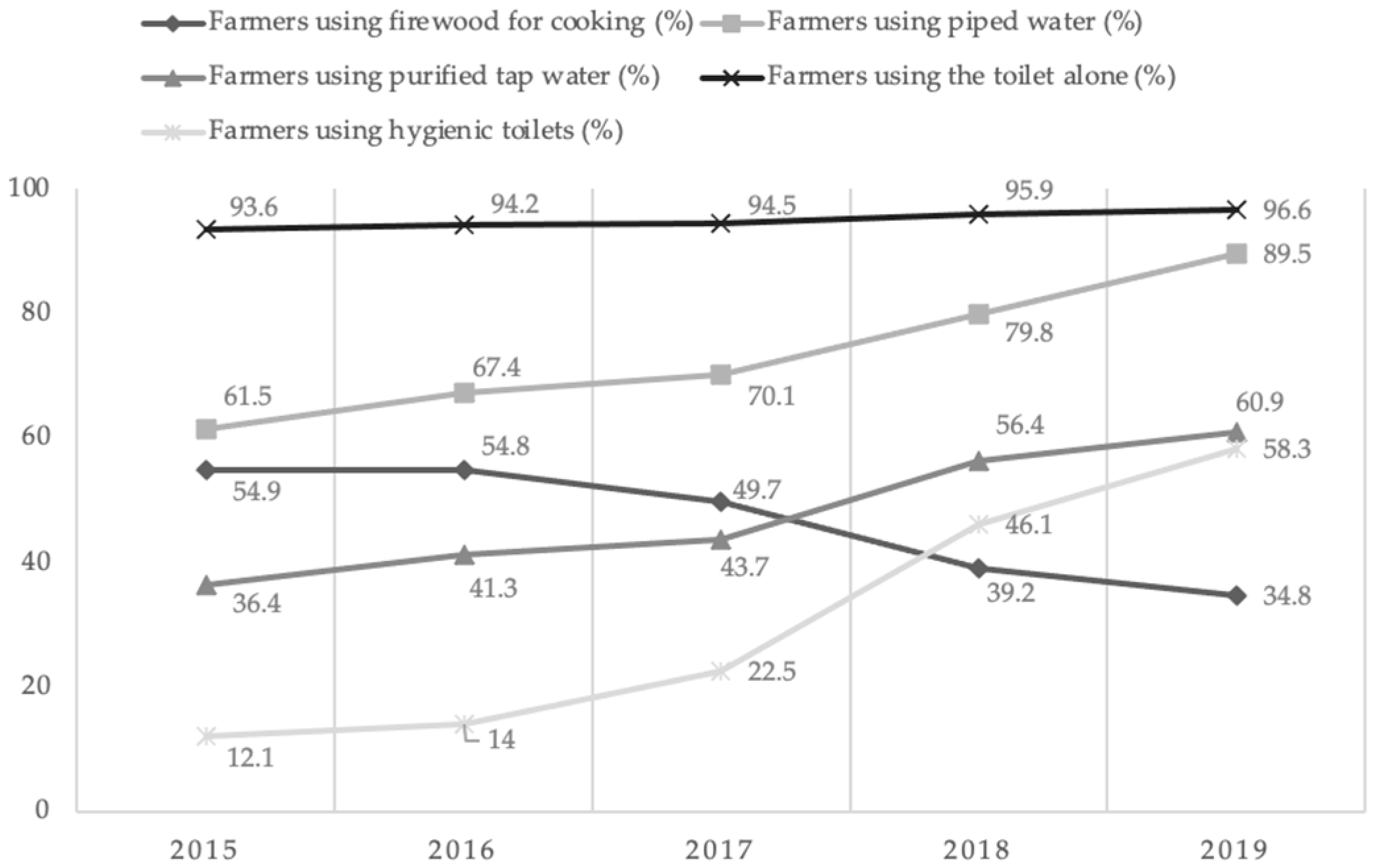

2.2. Achievements

2.3. Research

2.4. Other Poverty Alleviation Policies

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Description

3.2. Propensity Score Matching

3.3. Variable Description

3.3.1. Outcome Variables

3.3.2. Matching Variables

4. Results

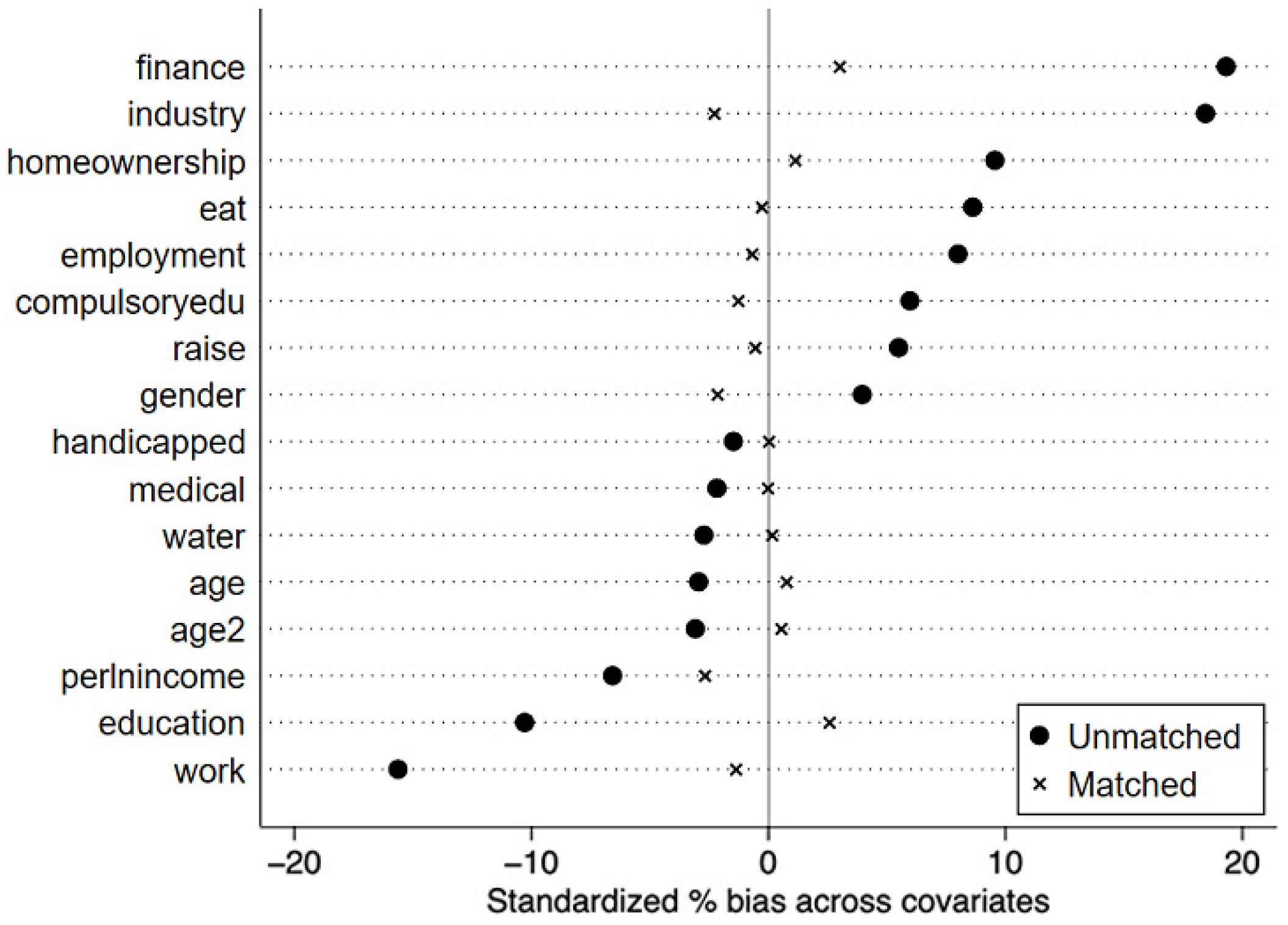

4.1. Balance Test

4.2. Common Support Test

4.3. Regression Results Analysis

4.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.4.1. Village Attributes

4.4.2. Household Attributes

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RPDH | Renovation Program of Dilapidated Houses |

| PSM | Propensity Score Matching |

| ATT | Average Treatment effect on the Treated |

References

- Wang, W. Construction of AHP-based Satisfaction Evaluation Index System of Targeted Poverty Alleviation Chinese Full Text. Stat. Decis. 2020, 36, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Shen, Y. Reflections and Suggestions on the New Challenges of Poverty Alleviation and Alleviation. China Educ. Dev. Poverty Reduct. Res. 2019, 2, 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, X.; Xiang, X. The research on influencing factors and countermeasures in rural dilapidated housing rehabilitation. J. Chongqing Univ. Sci. Ed. 2015, 21, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. From “Economic Stimulus” to “Social Assistance”—Analysis and Suggestions on the Renovation Policy of Dilapidated Houses in Rural Areas. J. Zhejiang Prov. Party Sch. 2012, 28, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Liu, H.; Lin, J. Effectiveness evaluation of precise poverty alleviation based on the perspective of farmers’ satisfaction. Stat. Decis. 2020, 36, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W. Rural Industry and Its Social Foundation in the Integrated Urban-Rural Development Process:A Case Study of Processing in Remote Villages under the Jurisdiction of City L, Zhejiang Province. Soc. Sci. China 2018, 41, 71–90. [Google Scholar]

- Varady, D.P.; Carrozza, M.A. Toward a Better Way to Measure Customer Satisfaction Levels in Public Housing: A Report from Cincinnati. Hous. Stud. 2000, 15, 797–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Praag, B.M.S.; Frijters, P.; Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. The Anatomy of Subjective Well-Being. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2003, 51, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, M.D.; Galiani, S.; Gertler, P.J.; Martinez, S.; Titiunik, R. Housing, Health, and Happiness. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 2009, 1, 75–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Wong, F.K.W.; Hui, E.C.M. Residential Satisfaction of Migrant Workers in China: A Case Study of Shenzhen. Habitat Int. 2014, 42, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukenya, J.O. An Analysis of Quality of Life, Income Distribution and Rural Development in West Virginia; West Virginia University: Morgantown, WV, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan, P.; White, M.P. How Can Measures of Subjective Well-Being Be Used to Inform Public Policy? Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 2, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Easterlin, R.A. Life Cycle Welfare: Trends and Differences. J. Happiness Stud. 2001, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chi, I.; Xu, L. Life Satisfaction of Older Chinese Adults Living in Rural Communities. J. Cross-Cult. Gerontol. 2013, 28, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, R.; Chen, Y. Analysis of the Influential Factors on Rural Residents’ Life Satisfaction. Stat. Res. 2012, 29, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.C.; Johnson, D.M. Avowed Happiness as an Overall Assessment of the Quality of Life. Soc. Indic. Res. 1978, 5, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Ravallion, M. The Developing World Is Poorer than We Thought, But No Less Successful in the Fight Against Poverty. Q. J. Econ. 2010, 125, 1577–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L. Evaluating China’s Poverty Alleviation Program: A Regression Discontinuity Approach. J. Public Econ. 2013, 101, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Su, B.; Liu, Y. Realizing Targeted Poverty Alleviation in China: People’s Voices, Implementation Challenges and Policy Implications. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2016, 8, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loayza, N.V.; Raddatz, C. The Composition of Growth Matters for Poverty Alleviation. J. Dev. Econ. 2010, 93, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, J. Poverty Alleviation through Labor Transfer in Rural China: Evidence from Hualong County. Habitat Int. 2021, 116, 102402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sui, Y. Problems and Countermeasures of Rural Dilapidated Housing Rehabilitation and Poverty Alleviation: Based on Supervision and Investigation in Shandong and Henan. Econ. Probl. 2016, 10, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guangxi Finance Department Subject Group. Study on the Use and Management of Subsidy Funds for Rural Dangerous House Improvement in Guangxi. Rev. Econ. Res. 2012, 47, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Du, J. A Study on the Effect of Rural Dangerous House Renovation Policy in China: Macro-Accounting and Empirical Analysis; Peking University Press: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, M. Evaluation of Remolding Farmer’s Dangerous House for Poor Families in Rural Areas Policy-Summary-Case Study of Zhejiang Hangzhou. J. Gansu Adm. Inst. 2011, 2, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Zhang, J. The Impact of Targeted Poverty Alleviation Policies on Registered Households’ Income Growth. Reform 2019, 12, 87–103. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, D.B. Estimating Causal Effects of Treatments in Randomized and Nonrandomized Studies. J. Educ. Psychol. 1974, 66, 688–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhu, H.; Weng, C. The Income Effect of Filing Cards Policy and the Role of Poverty-stricken Villages Policy. Finance Econ. 2021, 11, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ding, S. Long-term Change in Private Returns to Education in Urban China. Soc. Sci. China 2003, 6, 58–72+206. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Han, J. Can Multi-Targeted Poverty Alleviation Strategy Effectively Reduce Poverty in Poverty-stricken Areas? China Soft Sci. 2017, 12, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Ping, W.; Shan, Q.; Wang, J. Summary from China’s Poverty Alleviation Experience: Can Poverty Alleviation Policies Achieve Effective Income Increase? J. Manag. World 2022, 38, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Zhang, Q. Integration of Exogenous and Endogenous Development:Transformation and Improvement Path of China’s Targeted Poverty Alleviation Mechanism. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. Sci. Ed. 2017, 17, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. China’s Goal and Paths of Common Prosperity. Econ. Res. J. 2021, 56, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, R. Generalized Ordered Logit/Partial Proportional Odds Models for Ordinal Dependent Variables. Stata J. 2006, 6, 58–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Proportion (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 92.71 |

| Female | 7.29 | |

| Age | <30 | 0.88 |

| 30–39 | 7.26 | |

| 40–49 | 19.18 | |

| 50–59 | 40.47 | |

| >60 | 32.31 | |

| Education Background | Primary school and below | 54.15 |

| Junior high school | 40.92 | |

| High school | 4.7 | |

| Vocational school or technical secondary school | 0.08 | |

| Junior college or above | 0.15 | |

| Number of persons with disabilities | 0 | 80.43 |

| 1 | 16.13 | |

| ≥2 | 3.44 | |

| Burden of raising | <25% | 46.24 |

| 25–50% | 31.52 | |

| >50% | 22.24 | |

| Number of houses owned | 0 | 3.06 |

| 1 | 96.03 | |

| ≥2 | 0.91 | |

| Net household income per capita 1 | <6000 | 17.99 |

| 6000–10,000 | 46.39 | |

| 10,000–15,000 | 22.43 | |

| >15,000 | 13.19 | |

| Participate in RPDH | Yes | 45.89 |

| No | 54.11 |

| Category | Proportion (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction | Very satisfied | 73.48 |

| Satisfied | 26.09 | |

| Relatively satisfied | 0.43 | |

| Unsatisfied | 0 |

| Variable Name | Specific Definition |

|---|---|

| satisfaction * | “Very satisfied” = 3; “Satisfied” = 2; “Relatively satisfied” = 1. |

| Compulsoryedu 1 | Education poverty alleviation policy means that students in the compulsory education stage at home enjoy education poverty alleviation policy in at least one of the following ways: yes = 1, no = 0. ① Free nutritious meals; ② boarding subsidies; ③ free of tuition and miscellaneous fees; ④ free of book fees. |

| medical 1 | Medical poverty alleviation policy means that patients with serious diseases or chronic diseases in the family can enjoy medical poverty alleviation policy in at least one of the following ways: yes = 1, no = 0. ① If there are long-term chronic patients, do they enjoy services from a family doctor? ② If there are serious patients, do they go to the hospital to see a doctor and enjoy deposit-free, one-stop reimbursement and other services? |

| industry 1 | Farmers enjoy the industrial poverty alleviation policy in at least one of the following ways [31]: yes = 1, no = 0. ① Develop the industry independently with the help of funds, physical materials, or technical support provided by the government. ② Buy shares in cooperatives. ③ Develop the industry under the leadership of enterprises, cooperatives, and large households. |

| employment 1 | The employment poverty alleviation policy includes the following three aspects, and if farmers enjoy at least one aspect, they belong to the employment poverty alleviation policy: yes = 1, no = 0. ① Does anyone in the family participate in job training? ② Does the family arrange for migrant work through the government? ③ Does anyone in the family participate in public welfare posts or poverty alleviation workshops? |

| finance 1 | Financial poverty alleviation policy mainly refers to small loans for poverty alleviation, which is marked as 1 if the family has borrowed small loans for poverty alleviation and 0 otherwise. |

| age 2 | The householders’ ages. |

| gender 2 | male = 1, female = 0. |

| education 2 | Primary school and below = 1, middle school = 2, high school = 3, vocational school, technical secondary school = 4, junior college, and above = 5. |

| handicapped 3 | Number of disabled individuals. |

| raise 3 | Burden of raising a family: proportion of children under 16 years old and people over 60 years old in total population. |

| work 3 | Migrant worker proportion: proportion of people engaged in nonagricultural industries of total household population. |

| eat 4 | Meat frequency: eat meat whenever you want = 5; eat meat every third meal (no less than once a week) = 4; sometimes eat meat (no less than once a month) = 3; eat meat only on holidays = 2; never eat meat because you cannot afford it = 1; never eat meat = 0 for noneconomic reasons such as living habits. |

| water 4 | Drinking water safety: perennial safety of water quality = 3; unsafe water quality for no more than 1 month throughout the year = 2; annual unsafe water quality for more than 1 month = 1; I do not know = 0. |

| homeownership 4 | Number of houses owned. |

| lnperincome 4 | The logarithm of household net income per capita. |

| Variable Name | All the Samples | Treatment Group | Control Group | Difference of Significance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | Mean (1) | Mean (2) | Mean (3) | (2) − (3) = (4) | |

| Outcome variables | ||||||

| satisfaction | 1 | 3 | 2.731 (0.453) | 2.774 (0.422) | 2.694 (0.475) | 0.080 *** (0.177) |

| Matching variables | ||||||

| compulsoryedu | 0 | 1 | 0.322 (0.467) | 0.337 (0.473) | 0.309 (0.462) | 0.028 (0.018) |

| medical | 0 | 1 | 0.423 (0.494) | 0.417 (0.493) | 0.428 (0.495) | −0.011 (0.019) |

| industry | 0 | 1 | 0.964 (0.185) | 0.983 (0.131) | 0.949 (0.220) | 0.034 *** (0.007) |

| employment | 0 | 1 | 0.730 (0.444) | 0.749 (0.434) | 0.714 (0.452) | 0.035 * (0.017) |

| finance | 0 | 1 | 0.702 (0.458) | 0.749 (0.434) | 0.662 (0.473) | 0.087 *** (0.018) |

| age | 22 | 90 | 55.330 (11.003) | 55.154 (10.942) | 55.480 (11.056) | −0.326 (0.432) |

| gender | 0 | 1 | 0.927 (0.260) | 0.933 (0.251) | 0.922 (0.268) | 0.011 (0.102) |

| education | 1 | 5 | 1.512 (0.606) | 1.478 (0.601) | 1.540 (0.608) | −0.062 ** (0.024) |

| handicapped | 0 | 3 | 0.233 (0.510) | 0.229 (0.516) | 0.237 (0.504) | 0.008 (0.020) |

| raise | 0 | 100 | 34.060 (30.319) | 34.960 (30.641) | 33.296 (30.034) | 1.664 (1.189) |

| work | 0 | 100 | 21.821 (21.911) | 19.975 (21.139) | 23.387 (22.433) | 3.412 *** (0.857) |

| eat | 0 | 5 | 4.606 (0.775) | 4.642 (0.726) | 4.576 (0.813) | 0.066 ** (0.030) |

| water | 0 | 3 | 2.989 (0.150) | 2.987 (0.168) | 2.991 (0.132) | −0.004 (0.006) |

| homeownership | 0 | 4 | 1.037 (0.223) | 1.048 (0.244) | 1.027 (0.204) | 0.021 ** (0.009) |

| lnperincome | 8.118 | 11.142 | 9.101 (0.446) | 9.086 (0.422) | 9.115 (0.465) | −0.029 * (0.018) |

| N | 2617 | 1201 | 1416 | |||

| Variable Name | Mean Difference Test | Standardized Test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unmatched Matched | Treatment Group | Control Group | t Test | p Value | Standardized Differences | Drop (%) | |

| compulsoryedu | U | 0.3072 | 0.3093 | 1.52 | 0.128 | 6.0 | 78.3 |

| M | 0.3072 | 0.3433 | −0.31 | 0.775 | −1.3 | ||

| medical | U | 0.4172 | 0.428 | −0.56 | 0.577 | −2.2 | 98.1 |

| M | 0.4165 | 0.4167 | −0.01 | 0.992 | 0.0 | ||

| industry | U | 0.9825 | 0.9492 | 4.61 | 0.000 | 18.4 | 87.5 |

| M | 0.9833 | 0.9875 | −0.85 | 0.395 | −2.3 | ||

| employment | U | 0.7494 | 0.714 | 2.03 | 0.042 | 8.0 | 91.2 |

| M | 0.7496 | 0.7527 | −0.18 | 0.859 | −0.7 | ||

| finance | U | 0.7494 | 0.6617 | 4.91 | 0.000 | 19.3 | 84.5 |

| M | 0.7496 | 0.736 | 0.76 | 0.448 | 3.0 | ||

| age | U | 55.154 | 55.48 | −0.75 | 0.451 | −3.0 | 74.8 |

| M | 55.174 | 55.092 | 0.18 | 0.855 | 0.7 | ||

| age2 | U | 3161.6 | 3200.1 | −0.79 | 0.430 | −3.1 | 83.1 |

| M | 3163.8 | 3157.3 | 0.13 | 0.897 | 0.5 | ||

| gender | U | 0.9326 | 0.9223 | 1.00 | 0.316 | 3.9 | 45.0 |

| M | 0.9324 | 0.938 | −0.56 | 0.576 | −2.2 | ||

| education | U | 1.4779 | 1.5403 | −2.63 | 0.009 | −10.3 | 75.2 |

| M | 1.4783 | 1.4629 | 0.64 | 0.521 | 2.6 | ||

| handicapped | U | 0.229 | 0.2366 | −0.38 | 0.704 | −1.5 | 100.0 |

| M | 0.2296 | 0.2296 | 0.00 | 1.000 | 0.0 | ||

| raise | U | 34.959 | 33.296 | 1.40 | 0.162 | 5.5 | 89.5 |

| M | 34.993 | 35.168 | −0.14 | 0.887 | −0.6 | ||

| work | U | 19.975 | 23.387 | −3.98 | 0.000 | −15.7 | 91.1 |

| M | 19.925 | 20.229 | −0.35 | 0.725 | −1.4 | ||

| eat | U | 4.642 | 4.5756 | 2.19 | 0.029 | 8.6 | 96.5 |

| M | 4.6419 | 4.6442 | −0.08 | 0.938 | −0.3 | ||

| water | U | 2.9867 | 2.9908 | −0.7 | 0.481 | −2.7 | 95.0 |

| M | 2.9866 | 2.9864 | 0.03 | 0.977 | 0.1 | ||

| homeownership | U | 1.0483 | 1.0268 | 2.45 | 0.014 | 9.5 | 88.3 |

| M | 1.0434 | 1.0409 | 0.27 | 0.789 | 1.1 | ||

| perlnincome | U | 9.0856 | 9.1148 | −1.67 | 0.094 | −6.6 | 59.1 |

| M | 9.0838 | 9.0958 | −0.67 | 0.503 | −2.7 | ||

| Sample | Ps R2 | LR chi2 | MeanBias | MedBias | B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unmatched | 0.025 | 90.73 | 7.8 | 6.3 | 37.5 |

| Matched | 0.001 | 3.19 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 7.3 |

| Matched Sample Classification | Outside | Within | All the Samples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment group | 3 | 1198 | 1201 |

| Control group | 0 | 1416 | 1416 |

| All the samples | 3 | 2614 | 2617 |

| Nearest Neighbor Matching (K = 4) | Caliper Matching | Nuclear Matching | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATT | 0.074 *** (3.096) | 0.080 *** (4.419) | 0.077 *** (4.209) |

| Treatment group | 1198 | 1198 | 1198 |

| Control group | 1416 | 1390 | 1410 |

| All the samples | 2614 | 2588 | 2617 |

| Methods | Category | Poverty-Stricken Village | Non-Poverty-Stricken Village |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nearest neighbor matching (K = 4) | ATT | 0.029 (0.771) | 0.096 *** (3.073) |

| Treatment group | 557 | 644 | |

| Control group | 562 | 834 | |

| All the samples | 1119 | 1478 | |

| Caliper matching | ATT | 0.034 (0.771) | 0.098 *** (3.073) |

| Treatment group | 542 | 633 | |

| Control group | 559 | 829 | |

| All the samples | 1101 | 1462 | |

| Nuclear matching | ATT | 0.038 (1.273) | 0.112 *** (4.760) |

| Treatment group | 556 | 644 | |

| Control group | 562 | 834 | |

| All the samples | 1118 | 1478 |

| Methods | Category | Minimal-Assurance Households and Five-Assurance Households | General-Assurance Households |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nearest neighbor matching (K = 4) | ATT | 0.067 * (1.660) | 0.093 *** (3.421) |

| Treatment group | 387 | 804 | |

| Control group | 436 | 967 | |

| All the samples | 823 | 1771 | |

| Caliper matching | ATT | 0.064 * (1.660) | 0.093 *** (3.421) |

| Treatment group | 386 | 804 | |

| Control group | 432 | 944 | |

| All the samples | 818 | 1748 | |

| Nuclear matching | ATT | 0.075 ** (2.360) | 0.077 *** (3.576) |

| Treatment group | 387 | 804 | |

| Control group | 436 | 961 | |

| All the samples | 823 | 1765 |

| Generalized Ordered Logit Model | Traditional Ordered Logit Model | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | |||||||||

| RPDH lnoperate | 0.149 | 0.043 *** | 0.043 *** | ||||||

| (1.48) | (3.86) | (3.89) | |||||||

| RPDH lnsalary | 0.139 | 0.033 *** | 0.033 *** | ||||||

| (1.55) | (3.35) | (3.40) | |||||||

| RPDH lnperincome | 0.174 * | 0.043 *** | 0.043 *** | ||||||

| (1.82) | (4.18) | (4.23) | |||||||

| compulsory-edu | −0.948 | −0.050 | −0.918 | −0.079 | −0.920 | −0.044 | −0.053 | −0.082 | −0.047 |

| (−1.27) | (−0.47) | (−1.23) | (−0.74) | (−1.23) | (−0.41) | (−0.50) | (−0.77) | (−0.44) | |

| medical | 0.086 | −0.001 | 0.101 | −0.004 | 0.146 | −0.002 | −0.003 | −0.005 | −0.003 |

| (0.12) | (−0.01) | (0.14) | (−0.04) | (0.21) | (−0.02) | (−0.03) | (−0.05) | (−0.04) | |

| industry | 2.364 ** | −0.489 * | 2.266 ** | −0.472 * | 2.292 ** | −0.504 * | −0.451 * | −0.433 * | −0.463 * |

| (2.53) | (−1.86) | (2.41) | (−1.80) | (2.45) | (−1.91) | (−1.72) | (−1.65) | (−1.76) | |

| employment | 0.783 | 0.354 *** | 0.732 | 0.345 *** | 0.735 | 0.363 *** | 0.358 *** | 0.348 *** | 0.367 *** |

| (1.23) | (3.34) | (1.12) | (3.25) | (1.13) | (3.43) | (3.38) | (3.29) | (3.47) | |

| finance | −0.155 | −0.059 | −0.117 | −0.047 | −0.186 | −0.058 | −0.061 | −0.048 | −0.060 |

| (−0.22) | (−0.58) | (−0.17) | (−0.46) | (−0.27) | (−0.57) | (−0.60) | (−0.48) | (−0.59) | |

| age | −0.267 | 0.071 ** | −0.252 | 0.078 ** | −0.257 | 0.077 ** | 0.070 ** | 0.077 ** | 0.076 ** |

| (−0.83) | (2.27) | (−0.81) | (2.51) | (−0.82) | (2.49) | (2.24) | (2.48) | (2.46) | |

| age2 | 0.003 | −0.001 ** | 0.003 | −0.001 ** | 0.003 | −0.001 ** | −0.001 ** | −0.001 ** | −0.001 ** |

| (0.96) | (−2.33) | (0.97) | (−2.55) | (0.97) | (−2.54) | (−2.29) | (−2.52) | (−2.51) | |

| gender | 0.699 | −0.137 | 0.555 | −0.128 | 0.796 | −0.114 | −0.133 | −0.125 | −0.110 |

| (0.59) | (−0.77) | (0.47) | (−0.72) | (0.68) | (−0.65) | (−0.75) | (−0.71) | (−0.62) | |

| education | −0.672 | −0.087 | −0.710 | −0.089 | −0.716 | −0.086 | −0.088 | −0.090 | −0.087 |

| (−1.21) | (−1.13) | (−1.28) | (−1.16) | (−1.28) | (−1.11) | (−1.14) | (−1.17) | (−1.12) | |

| handicapped | −0.313 | −0.117 | −0.295 | −0.110 | −0.368 | −0.117 | −0.117 | −0.110 | −0.117 |

| (−0.52) | (−1.35) | (−0.50) | (−1.27) | (−0.6 2) | (−1.34) | (−1.35) | (−1.27) | (−1.35) | |

| raise | −0.001 | 0.004 * | −0.000 | 0.005 ** | −0.001 | 0.004 * | 0.004 ** | 0.005 ** | 0.004 * |

| (−0.03) | (1.96) | (−0.02) | (2.18) | (−0.06) | (1.93) | (1.96) | (2.19) | (1.94) | |

| work | −0.010 | 0.001 | −0.014 | −0.001 | −0.011 | 0.000 | 0.001 | −0.001 | 0.000 |

| (−0.68) | (0.29) | (−0.90) | (−0.24) | (−0.72) | (0.19) | (0.25) | (−0.29) | (0.15) | |

| eat | 0.531 * | 0.261 *** | 0.524 * | 0.266 *** | 0.521 * | 0.264 *** | 0.266 *** | 0.271 *** | 0.269 *** |

| (1.88) | (4.78) | (1.86) | (4.87) | (1.84) | (4.84) | (4.88) | (4.97) | (4.93) | |

| water | −5.959 | 0.393 | −4.685 | 0.433 | −4.676 | 0.431 | 0.385 | 0.425 | 0.423 |

| (−0.01) | (1.47) | (−0.01) | (1.61) | (−0.01) | (1.60) | (1.46) | (1.61) | (1.59) | |

| homeowner-ship | −2.989 *** | 0.300 | −3.037 *** | 0.312 | −3.080 *** | 0.307 | 0.249 | 0.261 | 0.255 |

| (−3.58) | (1.32) | (−3.55) | (1.37) | (−3.60) | (1.35) | (1.11) | (1.15) | (1.13) | |

| Constant | 27.823 | −3.185 ** | 23.865 | −3.519 *** | 23.716 | −3.546 *** | — | — | — |

| (0.02) | (−2.51) | (0.02) | (−2.78) | (0.02) | (−2.79) | ||||

| N | 2617 | 2617 | 2617 | 2617 | 2617 | 2617 | 2617 | 2617 | 2617 |

| Variable | Pr (y = 1) | Pr (y = 2) | Pr (y = 3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | |||

| RPDH lnoperate | −0.001 | −0.007 *** | 0.008 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Control | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Model 2 | |||

| RPDH lnsalary | −0.001 | −0.005 *** | 0.006 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Control | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Model 3 | |||

| RPDH lnperincome | −0.001 | −0.007 *** | 0.008 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Control | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, T.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Wan, J. Impact and Analysis of the Renovation Program of Dilapidated Houses in China on Poor Peasant Households’ Life Satisfaction: A Survey of 2617 Peasant Households in Gansu Province. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15548. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315548

Zhang T, Xu Q, Zhang Q, Wan J. Impact and Analysis of the Renovation Program of Dilapidated Houses in China on Poor Peasant Households’ Life Satisfaction: A Survey of 2617 Peasant Households in Gansu Province. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):15548. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315548

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Tianyi, Qianqian Xu, Qi Zhang, and Jun Wan. 2022. "Impact and Analysis of the Renovation Program of Dilapidated Houses in China on Poor Peasant Households’ Life Satisfaction: A Survey of 2617 Peasant Households in Gansu Province" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 15548. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315548

APA StyleZhang, T., Xu, Q., Zhang, Q., & Wan, J. (2022). Impact and Analysis of the Renovation Program of Dilapidated Houses in China on Poor Peasant Households’ Life Satisfaction: A Survey of 2617 Peasant Households in Gansu Province. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15548. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315548