Using the Conceptual Framework for Examining Sport Teams to Understand Group Dynamics in Professional Soccer

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Authentic Leadership

2.2.2. Coaching Competency

2.2.3. Perceived Justice

2.2.4. Role Clarity/Ambiguity

2.2.5. Role Conflict

2.2.6. Group Cohesion

2.2.7. Team Conflict

2.2.8. Transactive Memory System

2.2.9. Collective Efficacy

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Cronbach’s Alpha Coefficients

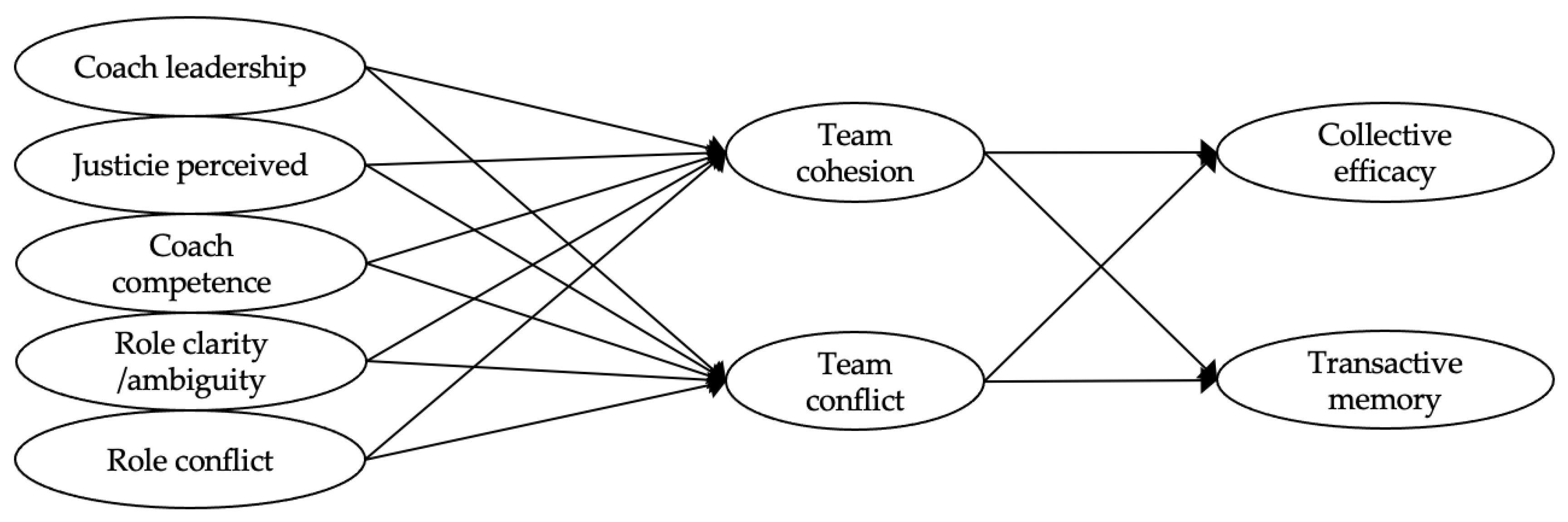

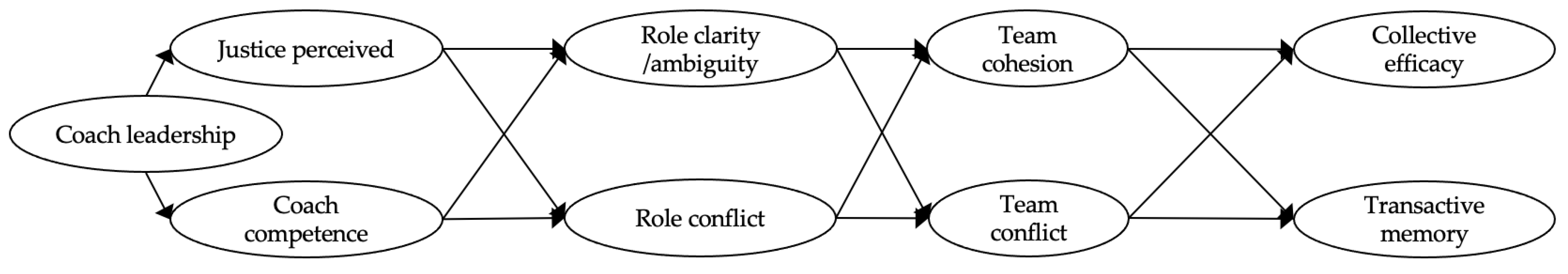

3.2. Model Testing

3.3. Indirect Effects

4. Discussion

Limitations, Future Perspectives, and Conclusions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eys, M.A.; Bruner, M.W.; Martin, L.J. The dynamic group environment in sport and exercise. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2019, 42, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, S.F.; Tsai, C.Y. Transformational leadership and athlete satisfaction: The mediating role of coaching competency. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2016, 28, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughead, T.M.; Fransen, K.; Van Puyenbroeck, S.; Hoffmann, M.D.; De Cuyper, B.; Vanbeselaere, N.; Boen, F. An examination of the relationship between athlete leadership and cohesion using social network analysis. J. Sports Sci. 2016, 34, 2063–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fuster-Parra, P.; García-Mas, A.; Ponseti, F.J.; Leo, F.M. Team performance and collective efficacy in the dynamic psychology of competitive team: A bayesian network analysis. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2015, 40, 98–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, E.; Tenenbaum, G.; Yang, Y. Cohesion, team mental models, and collective efficacy: Towards an integrated framework of team dynamics in sport. J. Sport Sci. 2015, 33, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Myers, N.D.; Beauchamp, M.R.; Chase, M.A. Coaching competency and satisfaction with the coach: A multi-level structural equation model. J. Sports Sci. 2011, 29, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carron, A.V.; Eys, M.A. Group Dynamics in Sport, 4th ed.; Fitness Information Technology: Morgantown, WV, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bosselut, G.; Heuzé, J.P.; Eys, M.A.; Fontayne, P.; Sarrazin, P. Athletes’ perceptions of role ambiguity and coaching competency in sport teams: A multilevel analysis. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2012, 34, 345–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leo, F.M.; González-Ponce, I.; Sánchez-Miguel, P.A.; Ivarsson, A.; García-Calvo, T. Role ambiguity, role conflict, team conflict, cohesion and collective efficacy in sport teams: A multilevel analysis. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2015, 20, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, F.M.; López-Gajardo, M.A.; Pulido, J.J.; González-Ponce, I. Multilevel analysis of evolution of team process and their relation to performance in semi-professional soccer. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2022, 17, 334–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Calvo, T.; Leo, F.M.; Gonzalez-Ponce, I.; Sánchez-Miguel, P.A.; Mouratidis, A.; Ntoumanis, N. Perceived coach-created and peer-created motivational climates and their associations with team cohesion and athlete satisfaction: Evidence from a longitudinal study. J. Sports Sci. 2014, 32, 1738–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Backer, M.; Boen, F.; Ceux, T.; De Cuyper, B.; Høigaard, R.; Callens, F.; Fransen, K.; Vande Broek, G. Do perceived justice and need support of the coach predict team identification and cohesion? Testing their relative importance among top volleyball and handball players in Belgium and Norway. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2011, 12, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sherwin, I.; Campbell, M.J.; MacIntyre, T.E. Talent development of high performance coaches in team sports in Ireland. European J. Sport Sci. 2016, 17, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikbin, D.; Hyun, S.; Albooyeh, A.; Foroughu, B. Effects of perceived justice for coaches on athletes’ satisfaction, commitment, effort, and team unity. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 2014, 45, 100–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.J.; Arthur, C.A.; Hardy, J.; Callow, N.; Williams, D. Transformational leadership and task cohesion in sport: The mediating role of intrateam communication. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2013, 14, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L.; Wernsing, T.S.; Peterson, S.J. Authentic leadership: Development and validation of a theory-based measure. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 89–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fusco, T.; O’Riordan, S.; Palmer, S. An existential approach to authentic leadership development: A review of the existential coaching literature and its’ relationship to authentic leadership. Coach. Psychol. 2015, 11, 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- García-Guiu, C.; Molero, F.; Moya, M.; Moriano, J.A. Authentic leadership, group cohesion and group identification in security and emergency teams. Psicothema 2015, 27, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, A.; Vitória, A.; Magalhães, A.; Ribeiro, N.; Pina e Cunha, M. Are authentic leaders associated with more virtuous, committed, and potent teams? Leadersh. Q. 2013, 24, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J. Organizational justice: Yesterday, today, and tomorrow. J. Manag. 1990, 16, 399–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, N.D.; Feltz, D.L.; Maier, K.S.; Wolfe, E.W.; Reckase, M.D. Athletes’ evaluations of their head coach’s coaching competency. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2006, 77, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, R.L.; Wolfe, D.M.; Quinn, R.P.; Snoek, J.D.; Rosenthal, R.A. Occupational Stress: Studies in Role Conflict and Ambiguity; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Barling, J.; Kelloway, E.K.; Zacharatos, A. Development and effects of transformational leaderhip in adolescents. Leadersh. Q. 2000, 11, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eys, M.A.; Carron, A.V. Role ambiguity, task cohesion, and task zelf-efficacy. Small Group Res. 2001, 32, 356–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carron, A.V.; Brawley, L.R.; Widmeyer, W.N. The Measurement of Cohesiveness in Sport Groups. In Advances in Sport and Exercise Psychology Measurement; Duda, J.L., Ed.; Fitness Information Technology: Morgantown, WV, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Carron, A.V.; Colman, M.M.; Wheeler, J. Cohesion, and performance in sport. A meta-analysis. J. Sport Exerc. Pshycol. 2002, 24, 168–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, F.M.; López-Gajardo, M.A.; González-Ponce, I.; García-Calvo, T.; Benson, A.J.; Eys, M.A. How socialization tactics relate to role clarity, cohesion, and intentions to return in soccer teams. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2020, 50, 101735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuzé, J.P.; Raimbault, N.; Fontayne, P. Relationships between cohesion, collective efficacy and performance in professional basketball teams: An examination of mediating effects. J. Sports Sci. 2006, 24, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wall, J.A.; Castiller, R.R. Conflict and its management. J. Manag. 1995, 21, 515–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, K.F.; Carron, A.V.; Martin, L.J. Athlete perceptions of intra-group conflict in sport teams. Sport Exerc. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 10, 4–18. [Google Scholar]

- Tekleab, A.G.; Quigley, N.R.; Tesluk, P.E. A longitudinal study of team conflict, conflict management, cohesion, and team effectiveness. Group Organ. Manag. 2009, 34, 170–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, F.M.; González-Ponce, I.; Amado, D.; Pulido, J.J.; García-Calvo, T. An approachment to group processes in female professional sport. Eur. J. Hum. Mov. 2016, 36, 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Heuzé, J.P.; Bosselut, G.; Thomas, J.P. Should the coaches of elite female handball teams focus on collective efficacy or group cohesion? Sport Psychol. 2007, 21, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozub, S.A.; McDonnell, J.F. Exploring the relationship between cohesion and collective efficacy in rugby teams. J. Sport Behav. 2000, 23, 120–129. [Google Scholar]

- Mell, J.N.; Van Knippenberg, D.; Van Ginkel, W.P. The catalyst effect: The impact of transactive memory system structure on team performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 1154–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccaro, S.J.; Blair, V.; Peterson, C.; Zazanis, M. collective efficacy. In Self-Efficacy, Adaptation, and Adjustment: Theory, Research, and Application; Maddux, J.E., Ed.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 305–328. ISBN 0306448750. [Google Scholar]

- Paradis, K.F.; Loughead, T. Examining the mediating role of cohesion between athlete leadership and athlete satisfaction in youth sport. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 2012, 43, 117–136. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead, A.B. Cognitive interdependence and convergent expectations in transactive memory. J. Personal. Social Psychol. 2001, 81, 1080–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, D.M. Transactive memory: A contemporary analysis of the group mind. In Theories of Group Behavior; Mullen, B., Goethals, G.R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1986; pp. 185–208. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, S.; Dumville, B.C. Team mental models in a team knowledge framework: Expending theory and measurement across disciplinary boundaries. J. Organ. Behav. 2001, 22, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prichard, J.S.; Ashleigh, M.J. The effects of team-skills training on transactive memory and performance. Small Group Res. 2007, 38, 696–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- González-Ponce, I.; Jiménez, R.; Leo, F.M.; Sánchez-Oliva, D.; Pulido, J.J.; García-Calvo, T. Validation into Spanish of the athletes´ perceptions of coaching competency scale. J. Sport Pshychol. 2017, 26, 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, N.D.; Chase, M.A.; Beauchamp, M.R.; Jackson, B. Athletes’ perceptions of coaching competency scale II-High School Teams. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2010, 70, 477–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A. On the dimensionality of organizational justice: A construct validation of a measure. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leo, F.M.; González-Ponce, I.; Sánchez-Oliva, D.; Pulido, J.J.; García-Calvo, T. Role ambiguity: Translation to spanish and analysis of scale structure. Small Group Res. 2017, 48, 365–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, M.R.; Bray, S.R.; Eys, M.A.; Carron, A.V. Role ambiguity, role efficacy, and role performance: Multidimensional and mediational relationships within interdependent sport teams. Group Dyn. Theory Res. Pract. 2002, 6, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, M.R.; Bray, S.R. Role ambiguity and role conflict within interdependent teams. Small Group Res. 2001, 32, 133–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, F.M.; González-Ponce, I.; Sánchez-Oliva, D.; Pulido, J.J.; García-Calvo, T. Adaptation and validation in Spanish of the Group Environment Questionnaire (GEQ) with professional football players. Psicothema 2015, 27, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehn, K.A. A Multimethod examination of the benefits and detriments of intragroup conflict. Adm. Sci. Q. 1995, 40, 256–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, F.M.; González-Ponce, I.; Sánchez-Oliva, D.; Pulido, J.J.; García-Calvo, T. Adaptation and validation of the Transactive Memory System Scale in Sport (TMSS-S). Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2018, 13, 1015–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K. Measuring transactive memory systems in the field: Scale development and validation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leo, F.M.; García-Calvo, T.; Parejo, I.; Sánchez-Miguel, P.A.; Sánchez-Oliva, D. Interaction of cohesion and perceived efficacy, success expectations and performance in basketball teams. J. Sport Pshychol. 2010, 19, 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 8th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2019; ISBN 9780957260306. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacker, R.E.; Lomax, R.G. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling; Lawrence Eribaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, M.R.; Bray, S.R.; Eys, M.A.; Carron, A.V. Leadership behaviors and multidimensional role ambiguity perceptions in team sports. Small Group Rese. 2005, 36, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, N.; Fouquereau, E.; Bonnaud-Antignac, A.; Mokounkolo, R.; Colombat, P. The mediating role of organizational justice in the relationship between transformational leadership and nurses’ quality of work life: A cross-sectional questionnaire survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2013, 50, 1359–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeinabadi, H.; Rastegarpour, H. Factors affecting teacher trust in principal: Testing the effect of transformational leadership and procedural justice. Procedia-Social Behav. Sci. 2010, 5, 1004–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kiersch, C.E.; Byrne, Z.S. Is being authentic being fair? Multilevel examination of authentic leadership, justice, and employee outcomes. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2015, 22, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C.D.; Gitelson, R. A meta-analysis of the correlates of role conflict and ambiguity. J. Appl. Psychol. 1983, 68, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubre, T.C.; Collins, J.M. Jackson and Schuler (1985) Revisited: A meta- analysis of the relationships between role ambiguity, role conflict, and job performance. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.E. Role ambiguity and team cohesion in division one athletes. Communication Studies Undergraduate Publications, Presentations and Projects 9. 2012. Available online: https://pilotscholars.up.edu/cst_studpubs/9 (accessed on 21 November 2022).

| M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | α | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authentic leadership | 5.39 | 0.86 | −0.70 | 0.70 | 0.87 |

| Coaching competency | 4.07 | 0.53 | −0.47 | −0.33 | 0.90 |

| Perceived justice | 5.63 | 0.80 | −0.95 | 0.96 | 0.87 |

| Role clarity/role ambiguity | 7.65 | 1.33 | −1.30 | 1.91 | 0.95 |

| Role conflict | 1.67 | 0.62 | 1.08 | 1.01 | 0.73 |

| Group cohesion | 7.26 | 1.03 | −0.79 | 0.78 | 0.82 |

| Team conflict | 2.10 | 0.91 | 1.07 | 1.18 | 0.84 |

| Transactive memory system | 4.15 | 0.49 | −0.35 | −0.19 | 0.84 |

| Collective efficacy | 3.91 | 0.51 | −0.15 | 0.20 | 0.77 |

| X2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | AIC | BIC | ABIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 1789.699 | 310 | 0.809 | 0.784 | 0.091 | 0.250 | 32,074.2888 | 32,488.940 | 32,187.351 |

| Model 2 | 1725.402 | 310 | 0.817 | 0.793 | 0.089 | 0.220 | 31,987.737 | 32,402.388 | 32,100.799 |

| Model 3 | 975.045 | 310 | 0.914 | 0.903 | 0.061 | 0.057 | 31,127.015 | 31,541.667 | 31,240.078 |

| Model 4 (final) | 945.994 | 311 | 0.918 | 0.908 | 0.059 | 0.060 | 31,092.083 | 31,502.369 | 31,203.955 |

| Parameter | β |

|---|---|

| Authentic leadership→Role clarity | 0.402 *** |

| Authentic leadership→Role conflict | −0.668 *** |

| Authentic leadership→Cohesion | 0.551 *** |

| Authentic leadership→Team conflict | −0.507 *** |

| Authentic leadership→Transactive memory system | 0.491 *** |

| Authentic leadership→Collective efficacy | 0.333 *** |

| Perceived justice→Cohesion | 0.368 *** |

| Perceived justice→Team conflict | −0.373 *** |

| Perceived justice→Transactive memory system | 0.333 *** |

| Perceived justice→Collective efficacy | 0.226 *** |

| Coaching competency→Cohesion | 0.271 *** |

| Coaching competency→Team conflict | −0.211 ** |

| Coaching competency→Transactive memory | 0.236 ** |

| Coaching competency→Collective efficacy | 0.160 ** |

| Role clarity→Transactive memory system | 0.354 *** |

| Role clarity→Collective efficacy | 0.240 *** |

| Role conflict→Transactive memory system | −0.522 *** |

| Role conflict→Collective efficacy | −0.354 *** |

| Cohesion→Collective efficacy | 0.516 *** |

| Team conflict→Collective efficacy | −0.096 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González-Ponce, I.; Díaz-García, J.; Ponce-Bordón, J.C.; Jiménez-Castuera, R.; López-Gajardo, M.A. Using the Conceptual Framework for Examining Sport Teams to Understand Group Dynamics in Professional Soccer. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15782. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315782

González-Ponce I, Díaz-García J, Ponce-Bordón JC, Jiménez-Castuera R, López-Gajardo MA. Using the Conceptual Framework for Examining Sport Teams to Understand Group Dynamics in Professional Soccer. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):15782. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315782

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález-Ponce, Inmaculada, Jesús Díaz-García, José C. Ponce-Bordón, Ruth Jiménez-Castuera, and Miguel A. López-Gajardo. 2022. "Using the Conceptual Framework for Examining Sport Teams to Understand Group Dynamics in Professional Soccer" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 15782. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315782