Towards a Better Workplace Environment—Empirical Measurement to Manage Diversity in the Workplace

Abstract

1. Introduction

Diversity, Inclusion and Diversity Management—Measurement Tools

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Research Sample

2.2. 5P Architecture

- Indicators of diversity management in a given area were developed:

- -

- A list of diagnostic variables was prepared by selecting appropriate questions from the questionnaire of the referenced CATI survey, with an indication of the measurement method in a given area (i.e., assigning a numerical value to individual variants of the original variable in such a way that they indicated an increasing/decreasing level of the phenomenon—the state of diversity management in a given area of P1–P5).

- The metric properties of an index constructed from the full set of diagnostic variables of a given 5P architecture area were investigated as follows:

- (a)

- The internal consistency of an indicator was determined by assessing its reliability with the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. A measurement was considered reliable if, relative to the error, it mainly reflected the true result. One of the most commonly used techniques for measuring scale reliability is the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, which indicates to what extent a certain set of variables describes a single construct hidden in them. It can be interpreted as a measure of scale consistency (synthetic index). The coefficient can take values between 0 and 1. In this case, we estimated the proportion of the variance of the true score that was shared by the questions by comparing the sum of the variance of the questions and the variance of the total scale. If the questions did not produce a true score, but only an error (which was unknown and specific, and consequently uncorrelated across individuals), then the variance of the sum would be the same as the sum of the variances of the individual items—the coefficient alpha would be 0. If all items were perfectly reliable and measured the same thing (the true score), then the coefficient alpha would be equal to 1; values closer to 1 indicate a higher reliability of the indicator (scale). The reliability of a scale is usually considered to be high if the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient takes a value of at least 0.7. A coefficient of 0.5 is considered acceptable [31,32,33];

- (b)

- To examine the homogeneity of the index exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used [34]. This analysis involved several steps. First, the conditions for using EFA were checked: (a) It was assessed whether the sample size was sufficient using the STV (STV ratio, n:p, i.e., the ratio between the sample size and the number of diagnostic variables). It is usually assumed that the STV should be 10:1 [35]; since the sample included 800 items and the number of diagnostic variables for each indicator was max. 39, this condition was fulfilled for each of the indicators WP1–WP5. (b) Inter-relationships between diagnostic variables were assessed using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s sphericity test, verifying the null hypothesis that the correlation matrix between diagnostic variables was a unitary matrix [36] (if KMO > 0.5, and in Bartlett’s sphericity test gives p < 0.05, the set of variables is considered adequate to conduct factor analysis); (c) the diagonal values of the anti-image correlation matrix were analyzed, representing the individual values of the KMO measure for the individual variables. If the coefficients exceed 0.5, the set of variables meets the requirements of the KMO measure in relation to each item of the WP1 index separately [37]. Second, the method of extracting common variability was chosen; in each case, this was the principal components method, which is an adaptation of the classical Hotelling’s principal components method for the purposes of factor analysis and is in practice the most commonly used [38]. Thirdly, common variance resources (communality) were analyzed, i.e., a measure of the proportion of common variance presented by a given item (in other words, the amount of variance of a given item explained by factors) [39]. Fourth, in order to extract unambiguous factor structures, the Equamax orthogonal rotation was applied [40], as the correlation assessment of the distinguished components indicated a low degree of association for each of the indicators WP1–WP5. Fifth, the number of factors (components) was determined using first the Kaiser criterion (eigenvalue > 1) and then the Catell criterion (the number of factors is “cut off” when the scatter plot for the next factor becomes less steep—its slope is reduced) [41]. Sixth, the values of factor loadings, which are the correlation coefficients between a given item and the factor/component it represents, in the rotated component matrix were analyzed.

- On the basis of the analyses carried out, the diagnostic variables were selected within the given NPD index for which (a) the factor loadings were greater than the adopted threshold (as recommended by Stevens [42], they should exceed 0.4), (b) the common variability resources were relatively high (arbitrarily assumed to exceed 0.1, although it should be borne in mind that the adopted threshold is liberal).

- Exploratory factor analysis was again conducted for the reduced set of variables and the conditions discussed in 2b were re-checked. The reliability of the new indicator was also reassessed, both overall and in possibly distinguished sub-areas.

- The value of the synthetic index was determined as a summary of the assessment in the selected areas (the sum of the values of the individual diagnostic variables) [33].

3. Results

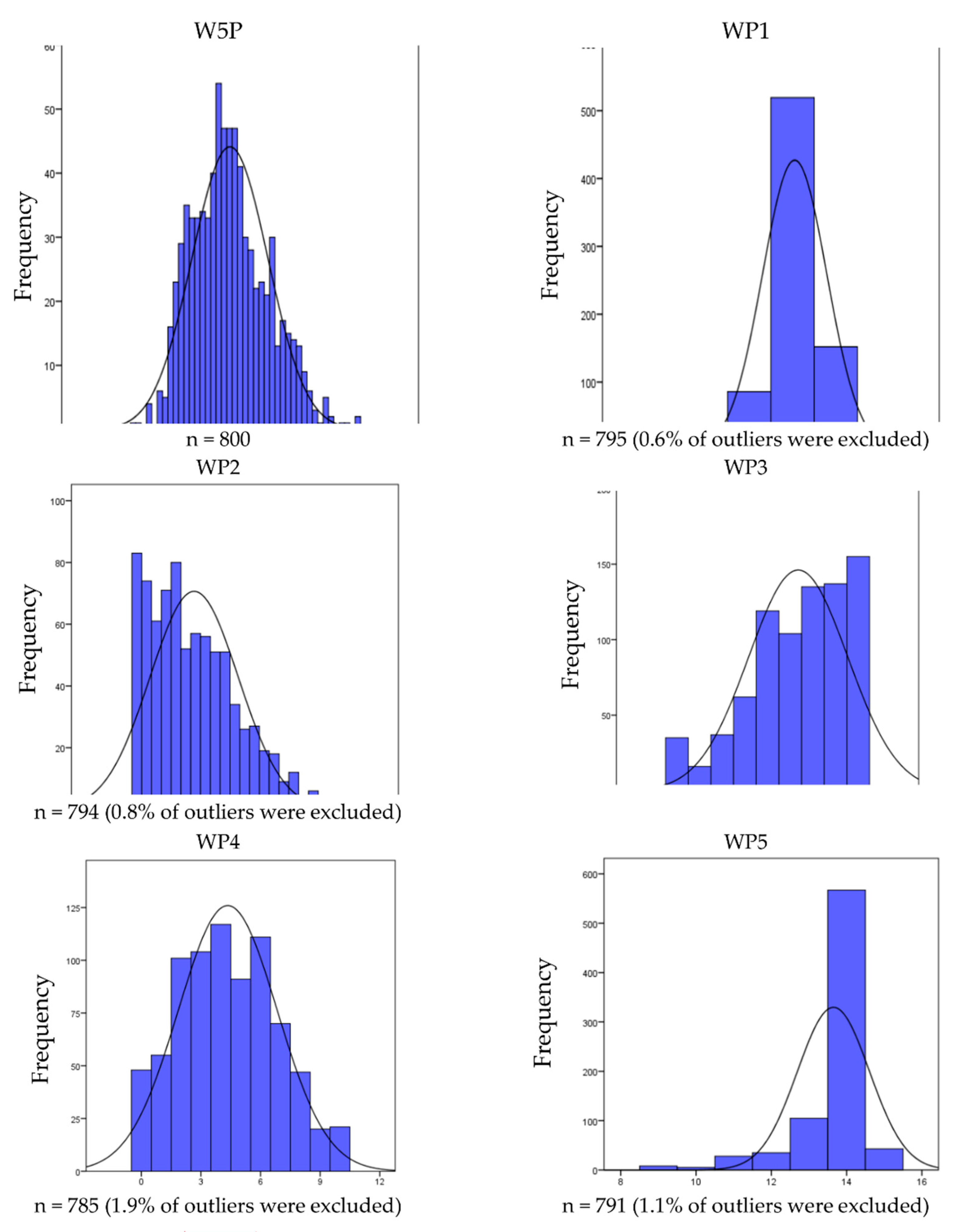

Distribution of the 5P Architecture Indicators

- Diversity management in the first area (P1) was at a relatively high level. This was evidenced by averages of around 9 points against a maximum index value of 11 points. Furthermore, not only the median, but also the other quartiles reached a value of 9, which means that half of the most typical entities achieved a WP1 value of exactly 9. In fact, the distribution was tightly clustered around this value—as many as 65% of all entities surveyed achieved a 9. The differentiation of companies was small in this respect (DAR = 0.83 points); nevertheless, there were companies with an atypically low level of development in this area of diversity management. Thus, there was a strong leftward slant of the WP1 index distribution and a strong slenderness of its distribution;

- Diversity management in the second area (P2), i.e., implementation of specific solutions in the organization, was not as well developed. The maximum value of the WP2 index was 28 points, while within the surveyed companies the highest score was 23, and the average was a mere 5.91 (DAR = 4.60 points), which indicates the strong differentiation among companies in this area. Half of the companies achieved a WP2 of no less than 5 points, a quarter achieved no more than 2 points and the other quarter achieved no less than 9 points for this indicator. However, the skewness and flattening of this distribution were not very strong;

- The degree of development of diversity management in the area of P3 could be judged at a relatively high level. There was a maximum possible score of 8 points, and this value was recorded in nearly 20% of the surveyed companies, while the average was around 5.5 points (DAR = 2.18 points). Half of the companies achieved a P3 score of no less than 6, 25% no higher than 4, and for 25% this index was no lower than 7. The skewness and flattening of this distribution were weak;

- P4 is much less developed—with a possible maximum of 18 points, the highest WP4 value in the sample is 10, and the average is around 4.3 points (STD = 2.49 points). Half of the companies achieved a WP4 of no less than 4 points, 25% no higher than 2 points and for 25% the index is no lower than 6 points. The skewness and flattening of this distribution were weak;

- Like its neighbor P1, the development of diversity management in P5 was also rated highly—71% of respondents scored 14 out of a maximum of 15 points. On average, P5 scores were approximately 13.7, with very low variation (DAR = 0.96), and, thus, a strong concentration of results around the mean (K = 6.784). Not only the median, but also the other quartiles reached a value of 14. The skewness of the WP5 distribution was strong and negative (entities with a WP5 score lower than the average prevailed);

- The global diversity management index average was approximately 38 points, with a sample maximum of 62 points, and there was relatively little variation (DAR = 7.1 points). Half of the companies achieved a W5P of no less than 37 points, 25% no higher than 33 points, and for 25% the index was no lower than 43 points. The skewness and flattening of this distribution were weak.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nkomo, S.; Bell, M.; Morgan, R.L.; Aparna, J. Thatcher Diversity at a Critical Juncture: New Theories for a Complex Phenomenon. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2019, 44, 498–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nantembelele, F.A.; Sowe, S. Corporate board diversity and its impact on the social performance of companies from emerging economies. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. 2021, 41, 6–20. [Google Scholar]

- Tasheva, S.; Hillman, A. Integrating Diversity at Different Levels: Multilevel Human Capital, Social Capital, and Demographic Diversity and Their Implications for Team Effectiveness. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2019, 44, 746–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharroubi, D. Global Workforce Diversity Management: Challenges Across the World. Econ. Manag. Spectr. 2021, 15, 28–37. [Google Scholar]

- Enehaug, H.; Spjelkavik, Ø.; Falkum, E.; Frøyland, K. Workplace Inclusion Competence and Employer Engagement. Nord. J. Work. Life Stud. 2022, 12, 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bärí, A. Diversity in the Workplace: Eye-Opening Interviews: To Jumpstart Conversations about Identity, Privilege, and Bias; Rockridge Press: Emeryville, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, A.E.; Zhu, R.; D’Ambrosio, C. Job quality and workplace gender diversity in Europe. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2021, 183, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, D.L. Diversity and Inclusion in Organizations. Research in Human Resource Management; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Drucker, P. Managing in the Next Society; Butterworth Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mor Barak, E.D. Managing Diversity: Toward a Globally Inclusive Work Place, 4th ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Luthra, P. Diversifying Diversity. Your Guide to Being an Active Ally of Inclusion in the Workplace; Diversifying Diversity ApS: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Seliverstova, Y.; Pierog, A. A Theoretical Study on Global Workforce Diversity Management, Its Benefits and Challenges. Cross-Cult. Manag. J. 2021, 23, 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, R.R. From affirmative action to affirming diversity. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1990, 68, 107–117. [Google Scholar]

- Loden, M.; Rosener, J.B. Workforce America! Managing Employee Diversity as a Vital Resource; Business One Irwin: Homewood, IL, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, R.R. Beyond Race and Gender. Unleashing the Power of Your Total Work Force by Managing Diversity; Amacom: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, R.R., Jr. Building a House for Diversity; Amacom: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gottardello, D. Diversity in the workplace: A review of theory and methodologies and propositions for future research. Sociol. Del Lavoro 2019, 153, 202–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, M.; Amershi, B.; Holmes, S.; Jablonski, H.; Luthi, E.; Matoba, K.; Plett, A.; Unruch, K. Training Manual. Diversity Management; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Özbilgin, M.F.; Tatli, A. Global Diversity Management: An Evidence-Based Approach; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Egan, M.L.; Bendick, M. Combining multicultural management and diversity into one course on cultural competence. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2008, 7, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booysen, L.A.E.; Bendl, K.; Pringle, J.K. (Eds.) Handbooks of Research Methods in Diversity Management, Equality and Inclusion at Work; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Seyedeh, F.; Ghasempour, G.; Fariborz, R.; Mohammad Reza, A.; Jawad, S. Analyzing the Impact of Diversity Management on Innovative Behaviors Through Employee Engagement and Affective Commitment. Iran. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 14, 649–667. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, A.; Melnik, M. Boston: Measuring Diversity in a Changing City; Boston Redevelopment Authority, Research Division: Boston, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Herring, C. Does diversity pay? Race, gender, and the business case for diversity. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2009, 74, 208–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheeks, M.; Yancey, G.B. Examining diversity climate through an intersectional lens. Psychol. Lead. Leadersh. 2022, 25, 12–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herdman, O.; McMillan-Capehart, A. Establishing a diversity program is not enough: Exploring the determinants of diversity climate. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S. HR Initiatives in Building Inclusive and Accessible Workplaces; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kossek, E.E.; Lobel, S.A.; Brown, J. Human Resource Strategies to Manage Workforce Diversity Examining ‘The Business Case’. In Handbook of Workplace Diversity; Konrad, A.M., Prasad, P., Pringle, J.K., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006; pp. 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- Nweiser, M.; Dajnoki, K. The Importance of Diversity Management In Relation With Other Functions Of Human Resource Management—A Systematic Review. Cross-Cult. Manag. J. 2022, 24, 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Chanda, A.; D’Netto, P.; Monga, M. Managing diversity through human re-source management: An international perspective and conceptual framework. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 20, 235–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rószkiewicz, M. Client Analysis; SPSS Poland: Krakow, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nawojczyk, M. Przewodnik Po Statystyce dla Socjologów; SPSS Poland Publishing House: Krakow, Poland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bedyńska, S.; Cypryańska, M. (Eds.) Statystyczny Drogowskaz. Praktyczne Wprowadzenie do Wnioskowania Statystycznego; Wydawnictwo Akademickie Sedno; SWPS: Warszawa, Poland, 2013; pp. 277–278. [Google Scholar]

- Wiktorowicz, J. Exploratory factor analysis in the measurement of the competencies of older workers. Econometrics 2016, 4, 48–60. [Google Scholar]

- Costello, A.B.; Osborne, J.B. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2005, 10, 154–169. [Google Scholar]

- Wiktorowicz, J. Międzypokoleniowy Transfer Wiedzy a Wydłużanie Okresu Aktywności Zawodowe; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego: Łódź, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Field, D. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS for Windows; Sage Publications: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; New Delhi, India, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Walesiak, M.; Bak, A. Use of factor analysis in marketing research. Oper. Res. Decis. 1997, 1, 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Szczucka, K. Polish Questionnaire of Adaptive and De-adaptive Perfectionism. Psychol. Społeczna 2010, 5, 71–95. [Google Scholar]

- Malarska, G. Statystyczna Analiza Danych Wspomagana Program SPSS; SPSS: Krakow, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Rusing SPSS (wyd. 2); Sage Publications: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, J.P. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Gross-Gołacka, E. Zarządzanie Różnorodnością. W kierunku Zróżnicowanych Zasobów Ludzkich w Organizacji; Difin: Warszawa, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiadou, A.; Gonzalez-Perez, M.; Olivas-Lujan, M.R. Diversity within Diversity Management: Where We Are, Where We Should Go and How We Are Getting Together. In Diversity within Diversity Management. Country-Based Perspective; Georgiadou, A., Gonzalez-Perez, M., Olivas-Lujan, M.R., Eds.; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2019; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Atewologun, D.; Mahalingam, R. Intersectionality as a Methodological Tools in Qualitative Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Research. In Handbooks of Research Methods in Diversity Management, Equality and Inclusion at Work; Booysen, L.A.F., Bendl, R., Pringle, J.K., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Seidl, J.; Neiva, E.R.; Faiad, C.; Murta, S.G. Age Diversity Management in Organizations Scale: Development and Evidence of Validity. Psico-USF Bragança Paul. 2022, 27, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, S.N.; van der Werff, L.; Thomas, K.M.; Plaut, V.C. The role of diversity practices and inclusion in promoting trust and employee engagement. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 45, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hapsari, C.; Stoffers, J.; Gunawan, A. The influence of generational diversity management and leader–member exchange on innovative work behaviors mediated by employee engagement. J. Asia-Pac. Bus. 2019, 20, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groeneveld, S. Diversity and employee turnover in the Dutch public sector: Does diversity management make a difference. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2010, 24, 594–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, P.F.; Avery, D.R. Diversity Climate in Organizations: Current Wisdom and Domains of Uncertainty. In Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management; Buckley, M.R., Halbesleben, J.R., Wheeler, A.R., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Ltd.: Bingley, UK, 2015; pp. 191–233. [Google Scholar]

- McCallaghan, S.; Heyns, M.M. The validation of a diversity climate measurement instrument for the South African environment. SA J. Ind. Psychol./SA Tydskr. Vir Bedryfsielkunde 2021, 47, 1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinwald, M.; Huettermann, H.; Bruch, H. Beyond the mean: Understanding firm-level consequences of variability in diversity climate perceptions. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 472–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, E.S.; Sears, G.J. CEO leadership styles and the implementation of organizational diversity practices: Moderating effects of social values and age. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 105, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.O.; Mor Barak, E. Understanding of diversity and inclusion in a perceived homogeneous culture: A study of organizational commitment and job performance among Korean employees. Adm. Soc. Work 2008, 32, 100–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.O.; Ha, R. Managing Diversity in U.S. Federal Agencies: Effects of Diversity and Diversity Management on Employee Perceptions of Organizational Performance. Public Adm. Rev. 2010, 70, 91–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuillot, A. Exploring the Role of Diversity Management During Early Internationalizing Firms’ Internationalization Process. Manag. Int. Rev. 2021, 61, 125–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, O.; Johnson, N. Understanding the Impact of Human Resource Diversity Practices on Firm Performance. Econ. J. Manag. Issues 2001, 13, 177–195. [Google Scholar]

- Guillemin, M.; Nicholas, R. Core Values at Work—Essential Elements of a Healthy Workplace. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Choi, J.O.; Hyun, S.S. A Study on Job Stress Factors Caused by Gender Ratio Imbalance in a Female-Dominated Workplace: Focusing on Male Airline Flight Attendants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Component | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| W5P.1 | W5P.2 | C | |

| WP2. Recruit and retain a diverse workforce in the organization | 0.706 | 0.056 | 0.501 |

| WP3. Expanding the market for goods and services | 0.681 | –0.074 | 0.469 |

| WP4. Promoting and communicating diversity | 0.675 | 0.205 | 0.498 |

| WP5. Review and evaluate the diversity actions taken in the organization | –0.118 | 0.838 | 0.716 |

| WP1. Planning and programming the vision and goals of diversity management in the organization | 0.266 | 0.741 | 0.619 |

| % of explained variance for a single component | 33.0 | 23.1 | |

| Cumulative | 33.0 | 56.1 | |

| Cronbach’s alpha coefficient | 0.425 | 0.413 | |

| 5P Architecture Indicators | Scope | Min. | Max. | Q1 | Me | Q3 | M | M ob | STD | Ace | K |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WP1. Planning and programming the vision and goals of diversity management in the organization | 0 ÷ 11 | 4 | 11 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9.02 | 9.08 | 0.83 | –1.609 | 7.612 |

| WP2. Recruit and retain a diverse workforce in the organization | 0 ÷ 28 | 0 | 23 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 5.91 | 5.59 | 4.60 | 0.793 | 0.228 |

| WP3. Expanding the market for goods and services | 0 ÷ 8 | 0 | 8 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 5.35 | 5.45 | 2.18 | –0.680 | –0.235 |

| WP4. Promoting and communicating diversity | 0 ÷ 18 | 0 | 10 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 4.35 | 4.31 | 2.49 | 0.194 | –0.628 |

| WP5. Review and evaluate the diversity actions taken in the organization | 0 ÷ 15 | 9 | 15 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 13.65 | 13.74 | 0.96 | –2.355 | 6.784 |

| W5P. Global Diversity Management Indicator | 0 ÷ 70 | 20 | 62 | 33 | 37 | 43 | 38.09 | 37.89 | 7.10 | 0.425 | –0.101 |

| WP1 | WP2 | WP3 | WP4 | WP5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WP1. Planning and programming the vision and goals of diversity management in the organization | Rho | 1.000 | 0.360 | 0.158 | 0.258 | 0.270 |

| p | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | ||

| WP2. Recruit and retain a diverse workforce in the organization | Rho | 0.360 | 1.000 | 0.227 | 0.325 | 0.072 |

| p | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | 0.042 * | ||

| WP3. Expanding the market for goods and services | Rho | 0.158 | 0.227 | 1.000 | 0.243 | 0.038 |

| p | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | 0.289 | ||

| WP4. Promoting and communicating diversity | Rho | 0.258 | 0.325 | 0.243 | 1.000 | 0.119 |

| p | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | <0.001 ** | 0.001 ** | ||

| WP5. Review and evaluate the diversity actions taken in the organization | Rho | 0.270 | 0.072 | 0.038 | 0.119 | 1.000 |

| p | <0.001 ** | 0.042 * | 0.289 | 0.001 ** | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gross-Gołacka, E.; Kupczyk, T.; Wiktorowicz, J. Towards a Better Workplace Environment—Empirical Measurement to Manage Diversity in the Workplace. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15851. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315851

Gross-Gołacka E, Kupczyk T, Wiktorowicz J. Towards a Better Workplace Environment—Empirical Measurement to Manage Diversity in the Workplace. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):15851. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315851

Chicago/Turabian StyleGross-Gołacka, Elwira, Teresa Kupczyk, and Justyna Wiktorowicz. 2022. "Towards a Better Workplace Environment—Empirical Measurement to Manage Diversity in the Workplace" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 15851. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315851

APA StyleGross-Gołacka, E., Kupczyk, T., & Wiktorowicz, J. (2022). Towards a Better Workplace Environment—Empirical Measurement to Manage Diversity in the Workplace. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15851. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315851