How and for Whom Is Mobile Phone Addiction Associated with Mind Wandering: The Mediating Role of Fatigue and Moderating Role of Rumination

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Mobile Phone Addiction and Mind Wandering

1.2. Fatigue as a Mediator

1.3. Rumination as a Moderator

1.4. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measurements

2.3.1. Mobile Phone Addiction

2.3.2. Mind Wandering

2.3.3. Fatigue

2.3.4. Rumination

2.3.5. Control Variables

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

3.2. Testing for the Mediating Effect of Fatigue

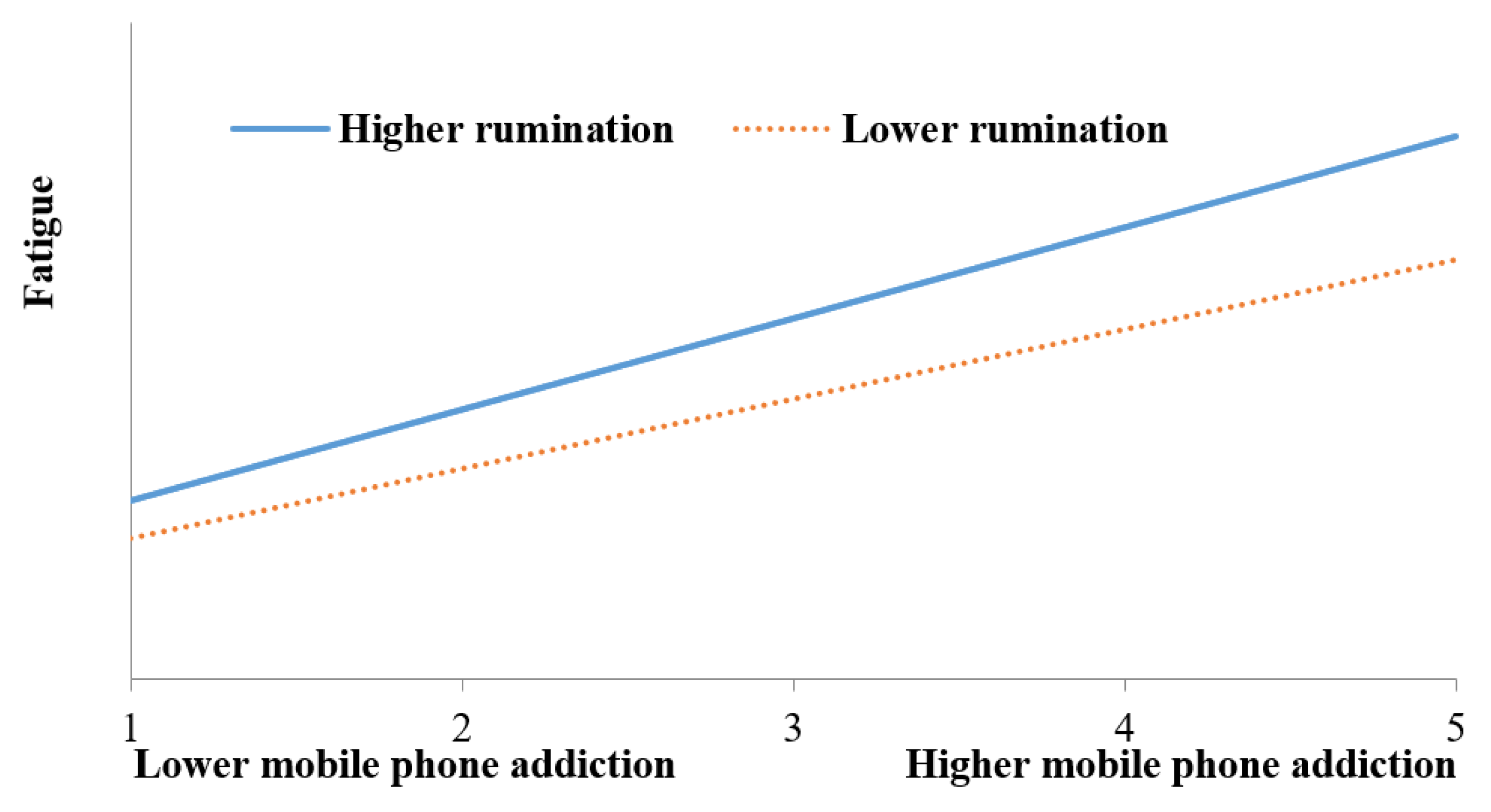

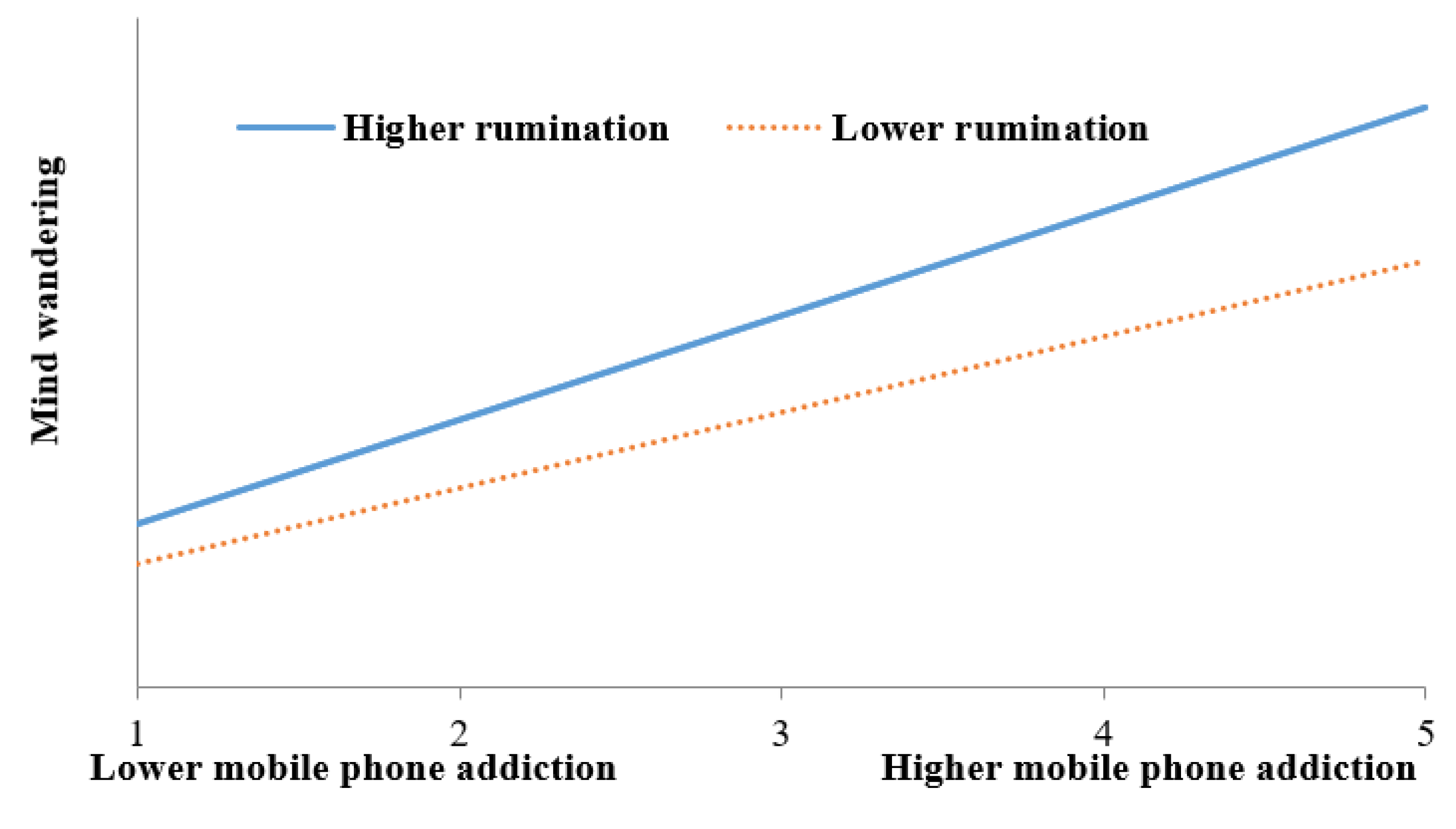

3.3. Testing for the Proposed Moderated Mediation Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Mobile Phone Addiction and Mind Wandering

4.2. Fatigue as a Mediator

4.3. Rumination as a Moderator

4.4. Limitations and Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Olson, J.A.; Sandra, D.A.; Colucci, É.S.; Al Bikaii, A.; Chmoulevitch, D.; Nahas, J.; Raz, A.; Veissière, S.P.L. Smartphone addiction is increasing across the world: A meta-analysis of 24 countries. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 129, 107138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwood, S.; Anglim, J.; Mallawaarachchi, S.R. Problematic smartphone use in a large nationally representative sample: Age, reporting biases, and technology concerns. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 122, 106848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Social Media Use Continues to Rise in Developing Countries but Plateaus across Developed Ones; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: http://www.pewinternet.org/2017/05/17/tech-adoption-climbs-among-older-adults (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- The 49nd Statistical Report on Internet Development in China; China Internet Network Information Center: Beijing, China, 2022; Available online: http://www.cnnic.net.cn/n4/2022/0401/c88-1131.html (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Bianchi, A.; Phillips, J.G. Psychological predictors of problem mobile phone use. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2005, 8, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chóliz, M. Mobile phone addiction: A point of issue. Addiction 2010, 105, 373–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billieux, J. Problematic use of the mobile phone: A literature review and a pathways model. Curr. Psychiatry Rev. 2012, 8, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Y.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, W. Reciprocal longitudinal relations between peer victimization and mobile phone addiction: The explanatory mechanism of adolescent depression. J. Adolesc. 2021, 89, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, D.; Yang, X.; Zhang, C.; Fan, C.; Zhou, Z. Perceived stress and mobile phone addiction in Chinese adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 87, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, S.; Sun, X.; Zhou, Z.; Fan, C.; Niu, G.; Liu, Q.; Rhee, S.H. Social networking site addiction and undergraduate students’ irrational procrastination: The mediating role of social networking site fatigue and the moderating role of effortful control. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e208162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, S.; Sun, X.; Niu, G.; Yang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, C. Mobile phone addiction and psychological distress among Chinese adolescents: The mediating role of rumination and moderating role of the capacity to be alone. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 279, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yan, Z.; Tang, W.; Yang, F.; Xie, X.; He, J. Mobile phone addiction levels and negative emotions among Chinese young adults: The mediating role of interpersonal problems. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 856–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, S.M.; Stockdale, L.; Summers, K. Problematic cell phone use, depression, anxiety, and self-regulation: Evidence from a three year longitudinal study from adolescence to emerging adulthood. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 96, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, S. The reciprocal longitudinal relationships between mobile phone addiction and depressive symptoms among Korean adolescents. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 58, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, X.; Kong, F.; Niu, G.; Fan, C. Mobile phone addiction and sleep quality among Chinese adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 72, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.X.; Wu, A.M.S. Effects of smartphone addiction on sleep quality among Chinese university students: The mediating role of self-regulation and bedtime procrastination. Addict. Behav. 2020, 111, 106552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadlington, L.J. Cognitive failures in daily life: Exploring the link with internet addiction and problematic mobile phone use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 51, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hong, W.; Liu, R.; Ding, Y.; Sheng, X.; Zhen, R. Mobile phone addiction and cognitive failures in daily life: The mediating roles of sleep duration and quality and the moderating role of trait self-regulation. Addict. Behav. 2020, 107, 106383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi, O. The association of mobile phone addiction proneness and self-reported road accident in Oyo State, Nigeria. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 2021, 6, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utami, R.H.; Kurniawan, R.; Magistarina, E. Internet-related Behavior and Mind Wandering. J. RAP Ris. Aktual Psikol. Univ. Negeri Padang 2021, 12, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, H.; Geng, F.; Song, X.; Hu, Y. Internet Gaming Disorder Increases Mind-Wandering in Young Adults. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 619072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcvay, J.C.; Kane, M.J. Does mind wandering reflect executive function or executive failure? Comment on smallwood and schooler (2006) and watkins (2008). Psychol. Bull 2010, 136, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVay, J.C.; Meier, M.E.; Touron, D.R.; Kane, M.J. Aging ebbs the flow of thought: Adult age differences in mind wandering, executive control, and self-evaluation. Acta Psychol. 2013, 142, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thomson, D.R.; Besner, D.; Smilek, D. A Resource-Control Account of Sustained Attention. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 10, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallwood, J.; Schooler, J.W. The restless mind. Psychol. Bull 2006, 132, 946–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seli, P.; Beaty, R.E.; Cheyne, J.A.; Smilek, D.; Oakman, J.; Schacter, D.L. How pervasive is mind wandering, really? Conscious Cogn. 2018, 66, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smallwood, J.; Fishman, D.J.; Schooler, J.W. Counting the cost of an absent mind: Mind wandering as an underrecognized influence on educational performance. Psychol. Bull 2007, 14, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Singer, J.L. Daydreaming: An Introduction to the Experimental Study of Inner Experience; Crown Publishing Group/Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1966; pp. 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Smallwood, J.; Obonsawin, M.; Reid, H. The effects of block duration and task demands on the experience of task unrelated thought. Imagin. Cogn. Personal. 2002, 22, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teasdale, J.D.; Dritschel, B.H.; Taylor, M.J.; Proctor, L.; Lloyd, C.A.; Nimmo-Smith, I.; Baddeley, A.D. Stimulus-independent thought depends on central executive resources. Mem. Cogn. 1995, 23, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Christoff, K.; Ream, J.M.; Gabrieli, J.D.E. Neural basis of spontaneous thought processes. Cortex 2004, 40, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, M.J.; Brown, L.H.; Mcvay, J.C.; Silvia, P.J.; Myin-Germeys, I.; Kwapil, T.R. For whom the mind wanders, and when: An experience-sampling study of working memory and executive control in daily life. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallwood, J.; Davies, J.B.; Heim, D.; Finnigan, F.; Sudberry, M.; O’Connor, R.; Obonsawin, M. Subjective experience and the attentional lapse: Task engagement and disengagement during sustained attention. Conscious. Cogn. 2004, 13, 657–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVay, J.C.; Kane, M.J.; Kwapil, T.R. Tracking the train of thought from the laboratory into everyday life: An experience-sampling study of mind wandering across controlled and ecological contexts. Psychon. B Rev. 2009, 16, 857–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mrazek, M.D.; Smallwood, J.; Schooler, J.W.; DeSteno, D. Mindfulness and mind-wandering: Finding convergence through opposing constructs. Emotion 2012, 12, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias Da Silva, M.R.; Rusz, D.; Postma-Nilsenová, M.; Faber, M. Ruminative minds, wandering minds: Effects of rumination and mind wandering on lexical associations, pitch imitation and eye behaviour. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e207578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, S.; Liu, Q.; Sun, X.; Zhou, Z. Mobile phone addiction and college students’ procrastination: Analysis of a moderated mediation model. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2018, 34, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, A.F.; Duke, K.; Gneezy, A.; Bos, M.W. Brain drain: The mere presence of one’s own smartphone reduces available cognitive capacity. J. Assoc. Consum. Res. 2017, 2, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, Q.; Fan, C. Mobile phone addiction and adolescents’ anxiety and depression: The moderating role of mindfulness. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 822–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallwood, J.; Nind, L.; O Connor, R.C. When is your head at? An exploration of the factors associated with the temporal focus of the wandering mind. Conscious Cogn. 2009, 18, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Tsay, S. The effect of acupressure with massage on fatigue and depression in patients with end-stage renal disease. J. Nurs. Res. 2004, 12, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, D.S.F.; Lee, D.T.F.; Man, N.W. Fatigue among older people: A review of the research literature. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010, 47, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.R.; Son, S.; Kim, K.K. Information and communication technology overload and social networking service fatigue: A stress perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åkerstedt, T.; Knutsson, A.; Westerholm, P.; Theorell, T.; Alfredsson, L.; Kecklund, G. Mental fatigue, work and sleep. J Psychosom Res 2004, 57, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeArmond, S.; Matthews, R.A.; Bunk, J.; Glazer, S. Workload and procrastination: The roles of psychological detachment and fatigue. Int. J. Stress. Manag. 2014, 21, 137–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denollet, J.; De Vries, J. Positive and negative affect within the realm of depression, stress and fatigue: The two-factor distress model of the global mood scale (GMS). J. Affect. Disord. 2006, 91, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bright, L.F.; Kleiser, S.B.; Grau, S.L. Too much facebook? An exploratory examination of social media fatigue. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 44, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, E.M.; Song, H.; Drent, A.M. Social comparison on Facebook: Motivation, affective consequences, self-esteem, and Facebook fatigue. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 64, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.W.; Lee, A.R. The moderating role of communication contexts: How do media synchronicity and behavioral characteristics of mobile messenger applications affect social intimacy and fatigue? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 97, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, T.; Chua, A.Y.K.; Goh, D.H. Characteristics of Social Network Fatigue. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Information Technology, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 15–17 April 2013; IEEE: Piscataway, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 431–438. [Google Scholar]

- Alzarea, B.K.; Patil, S.R. Mobile phone head and neck pain syndrome: Proposal of a new entity. Headache 2015, 14, 313–317. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.; Hong, Y.; Lee, S.; Won, J.; Yang, J.; Park, S.; Chang, K.; Hong, Y.; Department, O.R.S.; Inje, U.; et al. The effects of smartphone use on upper extremity muscle activity and pain threshold. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2015, 27, 1743–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, C.Y.; Lian, S.L.; Yang, C.; Zhou, Z.K. Effect of mobile phone addiction on college students’ depression: Mediation and moderation analyses. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2019, 27, 746–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unsworth, N.; McMillan, B.D. Similarities and differences between mind-wandering and external distraction: A latent variable analysis of lapses of attention and their relation to cognitive abilities. Acta Psychol. 2014, 150, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, J.J.; Otto, A.S.; Hassey, R.; Hirt, E.R. Chapter 10-Perceived mental fatigue and self-control. In Self-Regulation and Ego Control; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 185–202. [Google Scholar]

- Treynor, W.; Gonzalez, R.; Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cogn. Res. 2003, 27, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genet, J.J.; Siemer, M. Rumination moderates the effects of daily events on negative mood: Results from a diary study. Emotion 2012, 12, 1329–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, S.; Sun, X.; Liu, Q.; Chu, X.; Zhou, Z.; Lei, Y. When the capacity to be alone is associated with psychological distress among Chinese adolescents: Individuals with low mindfulness or high rumination may suffer more by their capacity to be alone. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, S.; Sun, X.; Niu, G.; Zhou, Z. Upward social comparison on SNS and depression: A moderated mediation model and gender difference. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2017, 49, 941–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munezawa, T.; Kaneita, Y.; Osaki, Y.; Kanda, H.; Minowa, M.; Suzuki, K.; Higuchi, S.; Mori, J.; Yamamoto, R.; Ohida, T. The association between use of mobile phones after lights out and sleep disturbances among Japanese adolescents: A nationwide cross-sectional survey. Sleep 2011, 34, 1013–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Doan, S.N.; Fuller-Rowell, T.E.; Evans, G.W. Cumulative risk and adolescent’s internalizing and externalizing problems: The mediating roles of maternal responsiveness and self-regulation. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 48, 1529–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallwood, J.; O’Connor, R.C. Imprisoned by the past: Unhappy moods lead to a retrospective bias to mind wandering. Cogn. Emot. 2011, 25, 1481–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, L. Linking psychological attributes to addiction and improper use of the mobile phone among adolescents in Hong Kong. J. Child. Media 2008, 2, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Gao, J.; Kong, Y.; Hu, Y.; Mei, S. The influence of alexithymia on mobile phone addiction: The role of depression, anxiety and stress. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 225, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Jin, L.; Li, Y.; Akram, H.R.; Saeed, M.F.; Ma, J.; Ma, H.; Huang, J. Alexithymia and mobile phone addiction in Chinese undergraduate students: The roles of mobile phone use patterns. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 97, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carriere, J.S.A.; Seli, P.; Smilek, D.; Mewhort, D.J.K. Wandering in both mind and body: Individual differences in mind wandering and inattention predict fidgeting. Can. J. Exp. Psychol. 2013, 67, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michielsen, H.J.; De Vries, J.; Van Heck, G.L. Psychometric qualities of a brief self-rated fatigue measure: The fatigue assessment scale. J. Psychosom. Res. 2003, 54, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, D.P.; Whisman, M.A. Gender differences in rumination: A meta-analysis. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2013, 55, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jose, P.E.; Brown, I. When does the gender difference in rumination begin? Gender and age differences in the use of rumination by adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2007, 37, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.; Kim, D.-J.; Cho, H.; Yang, S. The smartphone addiction scale: Development and validation of a short version for adolescents. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Parasuraman, S.; Sam, A.T.; Yee, S.W.K.; Chuon, B.L.C.; Ren, L.Y. Smartphone usage and increased risk of mobile phone addiction: A concurrent study. Int. J. Pharm. Investig. 2017, 7, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 119–120. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Ahn, H.; Choi, S.; Choi, W. The SAMS: Smartphone addiction management system and verification. J. Med. Syst. 2014, 38, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon-Hwan, B.; Mina, H.; Ho-Jang, K.; Hong, Y.C.; Jong-Han, L.; Joon, S.; Young, K.S.; Gab, L.C.; Kang, D.; Hyung-Do, C. Mobile phone use, blood lead levels, and attention deficit hyperactivity symptoms in children: A longitudinal study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, D.M.; Schneider, D.J.; Carter, S.R.; White, T.L. Paradoxical effects of thought suppression. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 53, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, D.M.; Hancock, J.T.; Bailenson, J.N.; Reeves, B. Psychological and physiological effects of applying self-control to the mobile phone. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e224464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walker, H.E.K.; Trick, L.M. Mind-wandering while driving: The impact of fatigue, task length, and sustained attention abilities. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2018, 59, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavia, L.; Cavani, P.; Di Blasi, M.; Giordano, C. Smartphone addiction inventory (SPAI): Psychometric properties and confirmatory factor analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.D.; Martin Ginis, K.A.; Bray, S.R.; Kavussanu, M. Exertion of self-control increases fatigue, reduces task self-efficacy, and impairs performance of resistance exercise. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2017, 6, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S.; Wisco, B.E.; Lyubomirsky, S. Rethinking rumination. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 3, 400–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, J.A.J.; Koenig, L.J. Response styles and negative affect among adolescents. Cogn. Res. 1996, 20, 13–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, H.L. The role of rumination in adjustment to a first coronary event. Diss. Abstr. Int. Sect. B Sci. Eng. 1999, 60, 410. [Google Scholar]

- Sydenham, M.; Beardwood, J.; Rimes, K.A. Beliefs about emotions, depression, anxiety and fatigue: A mediational analysis. Behav. Cogn. Psychoth. 2017, 45, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thorsteinsson, E.B.; Brown, R.F.; Owens, M.T. Modeling the effects of stress, anxiety, and depression on rumination, sleep, and fatigue in a nonclinical sample. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2019, 207, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffziger, S.; Ebner-Priemer, U.; Koudela, S.; Reinhard, I.; Kuehner, C. Induced rumination in everyday life: Advancing research approaches to study rumination. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2012, 53, 790–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Ren, J.; Wang, B.; Zhu, Q.; Antonietti, A. Effects of relaxing music on mental fatigue induced by a continuous performance task: Behavioral and erps evidence. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e136446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johansson, B.; Bjuhr, H.; Rönnbäck, L. Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) improves long-term mental fatigue after stroke or traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2012, 26, 1621–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galantino, M.L. Influence of yoga, walking, and mindfulness meditation on fatigue and body mass index in women living with breast cancer. Semin. Integr. Med. 2003, 1, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deyo, M.; Wilson, K.A.; Ong, J.; Koopman, C. Mindfulness and rumination: Does mindfulness training lead to reductions in the ruminative thinking associated with depression? Explor. J. Sci. Health 2009, 5, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 19.740 | 1.295 | 1 | |||||

| 2. Years of mobile phone usage | 5.280 | 2.356 | 0.196 ** | 1 | ||||

| 3. Mobile phone addiction | 2.603 | 0.609 | −0.084 ** | 0.070 ** | 1 | |||

| 4. Fatigue | 2.428 | 0.592 | −0.021 | 0.032 | 0.391 ** | 1 | ||

| 5. Mind wandering | 3.692 | 0.903 | −0.023 | 0.020 | 0.416 ** | 0.442 ** | 1 | |

| 6. Rumination | 2.318 | 0.499 | −0.029 | 0.005 | 0.163 ** | 0.117 ** | 0.106 ** | 1 |

| Model | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Total effect model | |||||||||

| R | R2 | F | df1 | df2 | p | B | SE | t | p |

| 0.42 | 0.18 | 70.81 | 5 | 1805 | <0.001 | ||||

| Constant | 2.211 *** | 0.418 | 5.285 | <0.001 | |||||

| Gender | −0.091 * | 0.023 | −2.186 | <0.05 | |||||

| Age | −0.002 | 0.023 | −0.078 | >0.05 | |||||

| Grade | 0.017 | 0.035 | 0.486 | >0.05 | |||||

| Years of mobile phone usage | −0.002 | 0.009 | −0.244 | >0.05 | |||||

| Mobile phone addiction | 0.630 *** | 0.034 | 18.690 | <0.001 | |||||

| Model 2: Mediator variable model | |||||||||

| R | R2 | F | df1 | df2 | p | B | SE | t | p |

| 0.40 | 0.16 | 62.22 | 5 | 1805 | <0.001 | ||||

| Constant | 1.841 *** | 0.267 | 6.904 | <0.001 | |||||

| Gender | −0.039 | 0.028 | −1.399 | >0.05 | |||||

| Age | −0.025 | 0.015 | −1.670 | >0.05 | |||||

| Grade | 0.058 ** | 0.022 | 2.646 | <0.01 | |||||

| Years of mobile phone usage | 0.002 | 0.006 | 0.327 | >0.05 | |||||

| Mobile phone addiction | 0.386 *** | 0.022 | 17.529 | <0.001 | |||||

| Model 3: Dependent variable model | |||||||||

| R | R2 | F | df1 | df2 | p | B | SE | t | p |

| 0.51 | 0.27 | 101.18 | 6 | 1084 | <0.001 | ||||

| Constant | 1.288 ** | 0.413 | 3.120 | <0.01 | |||||

| Gender | −0.071 | 0.039 | −1.816 | >0.05 | |||||

| Age | 0.011 | 0.022 | 0.475 | >0.05 | |||||

| Grade | −0.012 | 0.033 | −0.377 | >0.05 | |||||

| Years of mobile phone usage | −0.003 | 0.008 | −0.370 | >0.05 | |||||

| Mobile phone addiction | 0.437 *** | 0.036 | 12.237 | <0.001 | |||||

| Fatigue | 0.502 *** | 0.038 | 13.311 | <0.001 | |||||

| B | Boot SE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | ||||||

| Total effect of mobile phone addiction on mind wandering | 0.630 | 0.034 | 0.564 | 0.696 | |||||

| Direct effect of mobile phone addiction on mind wandering | 0.437 | 0.036 | 0.367 | 0.507 | |||||

| Indirect effect of fatigue | 0.194 | 0.018 | 0.159 | 0.232 | |||||

| Model | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Mediator variable model | |||||||||

| R | R2 | F | df1 | df2 | p | B | SE | t | p |

| 0.40 | 0.16 | 0.294 | 7 | 1803 | <0.001 | ||||

| Constant | 2.862 *** | 0.260 | 11.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| Gender | −0.041 | 0.028 | −1.475 | >0.05 | |||||

| Age | −0.026 | 0.015 | −1.774 | >0.05 | |||||

| Grade | 0.062 ** | 0.022 | 2.832 | <0.01 | |||||

| Years of mobile phone usage | 0.022 | 0.006 | 0.387 | >0.05 | |||||

| Mobile phone addiction | 0.368 *** | 0.022 | 16.570 | <0.001 | |||||

| Rumination | 0.073 ** | 0.027 | 2.672 | <0.01 | |||||

| Mobile phone addiction × Rumination | 0.098 * | 0.041 | 2.408 | <0.05 | |||||

| Model 2: Dependent variable model | |||||||||

| R | R2 | F | df1 | df2 | p | B | SE | t | p |

| 0.52 | 0.27 | 75.20 | 8 | 1802 | <0.001 | ||||

| Constant | 2.443 | 0.408 | 5.982 | <0.001 | |||||

| Gender | −0.072 | 0.039 | −1.823 | >0.05 | |||||

| Age | 0.010 | 0.022 | 0.442 | >0.05 | |||||

| Grade | −0.010 | 0.033 | −0.305 | >0.05 | |||||

| Years of mobile phone usage | −0.003 | 0.008 | −0.305 | >0.05 | |||||

| Fatigue | 0.495 *** | 0.038 | 13.073 | <0.001 | |||||

| Mobile phone addiction | 0.421 *** | 0.036 | 11.692 | <0.001 | |||||

| Rumination | 0.042 | 0.038 | 1.111 | >0.05 | |||||

| Mobile phone addiction × Rumination | 0.142 * | 0.061 | 2.322 | <0.05 | |||||

| Conditional direct effect analysis at values of rumination (M ± SD) | |||||||||

| B | SE | LLCI | ULCI | ||||||

| M − 1SD (1.819) | 0.350 | 0.049 | 0.255 | 0.446 | |||||

| M (2.318) | 0.421 | 0.036 | 0.351 | 0.492 | |||||

| M + 1SD (2.817) | 0.492 | 0.046 | 0.402 | 0.582 | |||||

| Conditional indirect effect analysis at values of rumination (M ± SD) | |||||||||

| B | Boot SE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | ||||||

| M – 1SD (1.819) | 0.158 | 0.020 | 0.122 | 0.200 | |||||

| M (2.318) | 0.182 | 0.018 | 0.150 | 0.219 | |||||

| M + 1SD (2.817) | 0.206 | 0.021 | 0.168 | 0.250 | |||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lian, S.; Bai, X.; Zhu, X.; Sun, X.; Zhou, Z. How and for Whom Is Mobile Phone Addiction Associated with Mind Wandering: The Mediating Role of Fatigue and Moderating Role of Rumination. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15886. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315886

Lian S, Bai X, Zhu X, Sun X, Zhou Z. How and for Whom Is Mobile Phone Addiction Associated with Mind Wandering: The Mediating Role of Fatigue and Moderating Role of Rumination. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):15886. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315886

Chicago/Turabian StyleLian, Shuailei, Xuqing Bai, Xiaowei Zhu, Xiaojun Sun, and Zongkui Zhou. 2022. "How and for Whom Is Mobile Phone Addiction Associated with Mind Wandering: The Mediating Role of Fatigue and Moderating Role of Rumination" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 15886. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315886

APA StyleLian, S., Bai, X., Zhu, X., Sun, X., & Zhou, Z. (2022). How and for Whom Is Mobile Phone Addiction Associated with Mind Wandering: The Mediating Role of Fatigue and Moderating Role of Rumination. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15886. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315886