The Impact of Job Insecurity on Knowledge-Hiding Behavior: The Mediating Role of Organizational Identification and the Buffering Role of Coaching Leadership

Abstract

1. Introduction

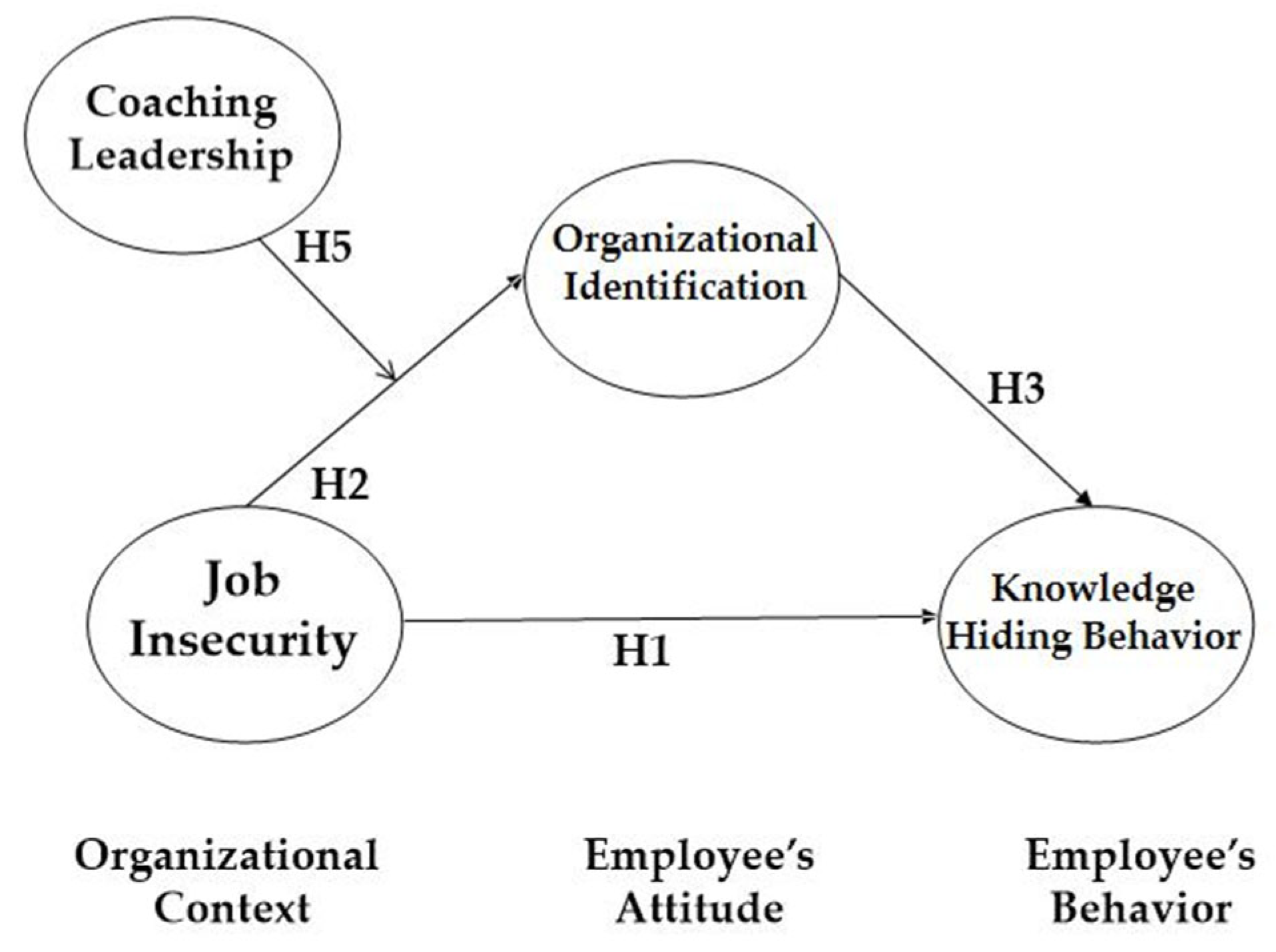

2. Theories and Hypotheses

2.1. Job Insecurity and Knowledge-Hiding Behavior

2.2. Job Insecurity and Organizational Identification

2.3. Organizational Identification and Knowledge-Hiding Behavior

2.4. Mediating Role of Organizational Identification between Job Insecurity and Knowledge-Hiding Behavior

2.5. Moderating Effect of Coaching Leadership on the Job Insecurity–Organizational Identification Link

3. Method

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Job Insecurity (Time Point One, Collected from Employees)

3.2.2. Coaching Leadership (Time Point One, Collected from Employees)

3.2.3. Organizational Identification (Time Point Two, Collected from Employees)

3.2.4. Knowledge-Hiding Behavior (Time Point Three, Collected from Employees’ Immediate Supervisors)

3.2.5. Control Variables

3.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Measurement Model

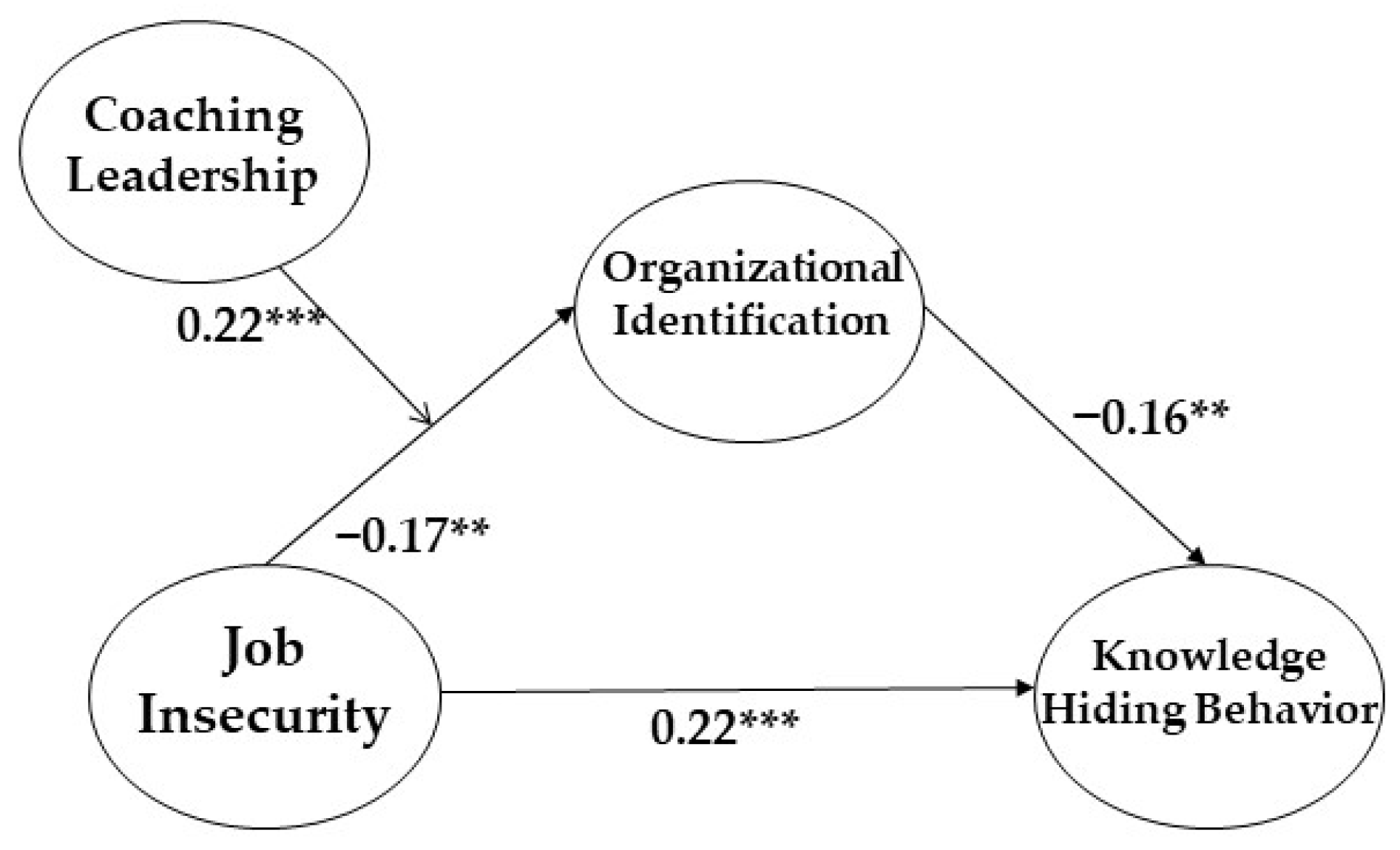

4.3. Structural Model

4.3.1. Result of Mediation Analysis

4.3.2. Result of Bootstrapping

4.3.3. Result of Moderation Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Studies

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fouad, N.A. Editor in chief’s introduction to essays on the impact of COVID-19 on work and workers. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 119, 103441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sergent, K.; Stajkovic, A.D. Women’s leadership is associated with fewer deaths during the COVID-19 crisis: Quantitative and qualitative analyses of United States governors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 771–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoss, M.K. Job insecurity: An integrative review and agenda for future research. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1911–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grote, G.; Pfrombeck, J. Uncertainty in aging and lifespan research: Covid-19 as catalyst for addressing the elephant in the room. Work. Aging Retire. 2020, 6, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurk, D.; Straub, C. Flexible employment relationships and careers in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 119, 10435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Shao, Y.; Li, G.; Guo, Y.; Zhan, X. The psychological implications of COVID-19 on employee job insecurity and its consequences: The mitigating role of organization adaptive practices. J. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 106, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staufenbiel, T.; König, C.J. A model for the effects of job insecurity on performance, turnover intention, and absenteeism. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashford, S.J.; Lee, C.; Bobko, P. Content, causes, and consequences of job insecurity: A theory-based measure and substantive test. Acad. Manag. J. 1989, 32, 803–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Huang, G.-H.; Ashford, S.J. Job insecurity and the changing workplace: Recent developments and the future trends in job insecurity research. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 335–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cuyper, N.; Mäkikangas, A.; Kinnunen, U.; Mauno, S.; DeWitte, H. Cross-lagged associations between perceived external employability, job insecurity, and exhaustion: Testing gain and loss spirals according to the conservation and resources theory. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 78, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Liu, T.; Yang, W.; Xia, F. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic Perception on Job Stress of Construction Workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022, 19, 10169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Lavaysse, L.M. Cognitive and affective job insecurity: A meta-analysis and a primary study. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 2307–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niesen, W.; Witte, H.D.; Battistelli, A. An explanatory model of job insecurity and innovative work behavior: Insights from social exchange and threat rigidity theory. Contemp. Occup. Health Psychol. 2014, 3, 18–34. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L.; Probst, T.M. A multilevel examination of affective job insecurity climate on safety outcomes. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berntson, E.; Näswall, K.; Sverke, M. The moderating role of employability in the association between job insecurity and exit, voice, loyalty and neglect. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2010, 31, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, A.; Sulea, C.; Vander Elst, T.; Fischmann, G.; Iliescu, D.; De Witte, H. The mediating role of psychological needs in the relation between qualitative job insecurity and counterproductive work behavior. Career Dev. Int. 2014, 19, 526–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Tang, C.; Akram, F.; Khan, M.L.; Chuadhry, M.A. Negative work attitudes and task performance: Mediating role of knowledge hiding and moderating role of servant leadership. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 963696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, L.; Qu, G. Explicating the business model from a knowledge-based view: Nature, structure, imitability and competitive advantage erosion. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 25, 23–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H. Why and when do people hide knowledge? J. Knowl. Manag. 2013, 17, 398–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Wu, D.; Liao, Z. Job insecurity and workplace deviance: The moderating role of locus of control. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2018, 46, 1673–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.S.; Chen, Z.X.; Ashford, S.J.; Lee, C.; Qian, J. A self-consistency motivation analysis of employee reactions to job insecurity: The roles of organization-based self-esteem and proactive personality. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 92, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callea, A.; Lo Presti, A.; Mauno, S.; Urbini, F. The associations of quantitative/qualitative job insecurity and well-being: The role of self-esteem. Int. J. Stress. Manag. 2019, 26, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Huang, G.H.; Lee, C.; Ren, X. Longitudinal effects of job insecurity on employee outcomes: The moderating role of emotional intelligence and the leader-member exchange. Asia. Pacific. J. Manag. 2012, 29, 709–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvishmotevali, M.; Ali, F. Job insecurity, subjective well-being and job performance: The moderating role of psychological capital. Int. J. Hospi. Manag. 2020, 87, 102462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar-Quintana, T.; Nguyen, T.H.H.; Araujo-Cabrera, Y.; Sanabria-Díaz, J.M. Do job insecurity, anxiety and depression caused by the COVID-19 pandemic influence hotel employees’ self-rated task performance? The moderating role of employee resilience. Int. J. Hospi. Manag. 2021, 94, 102868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, K.B.; Kroeck, K.G.; Sivasubramaniam, N. Effectiveness correlates of transformation and transactional leadership: A meta-analytic review of the MLQ literature. Leadersh. Q. 1996, 7, 385–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, E. Organizational Culture and Leadership, 3rd ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.J.; Kim, B.J. The performance implications of job insecurity: The sequential mediating effect of job stress and organizational commitment, and the buffering role of ethical leadership. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, C.E.; Zweig, D.; Webster, J.; Trougakos, J.P. Knowledge hiding in organizations. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 64–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, M.G. Central questions in organizational identification. Identity Organ. 1998, 24, 171–207. [Google Scholar]

- Dukerich, J.M.; Golden, B.R.; Shortell, S.M. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder: The impact of organizational identification, identity, and image on the cooperative behaviors of physicians. Adm. Sci. Q. 2002, 47, 507–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, R.M. Intergroup relations and organizational dilemmas-the role of categorization processes. Res. Organ. Behav. 1991, 13, 191–228. [Google Scholar]

- Bartel, C.A. Social comparisons in boundary-spanning work: Effects of community outreach on members’ organizational identity and identification. Adm. Sci. Q. 2001, 46, 379–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blader, S.L.; Tyler, T.R. Testing and extending the group engagement model: Linkages between social identity, procedural justice, economic outcomes, and extrarole behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogg, M.A.; Terry, D.J. The dynamic, diverse, and variable faces of organizational identity. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 150–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, H.Y.; Loi, R.; Foley, S.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, L. Perceptions of organizational context and job attitudes: The mediating effect of organizational identification. Asia. Pacific. J. Manag. 2013, 30, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Austin, W.G., Worchel, S., Eds.; Brooks/Cole: Monterey, CA, USA, 1979; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, J.B.; Marler, L.; Hester, K.; Frey, L.; Relyea, C. Construed external image and organizational identification: A test of the moderating influence of need for self-esteem. J. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 146, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirumbolo, A. The impact of job insecurity on counterproductive work behaviors: The moderating role of honesty–humility personality trait. J. Psychol. 2015, 149, 554–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.H.; Wellman, N.; Ashford, S.J.; Lee, C.; Wang, L. Deviance and exit: The organizational costs of job insecurity and moral disengagement. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiwen, F.; Hahn, J. Job insecurity in the COVID-19 pandemic on counterproductive work behavior of millennials: A time-lagged mediated and moderated model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.L. Trust and breach of the psychological contract. Adm. Sci. Q. 1996, 41, 574–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.L.; Wolfe Morrison, E. The development of psychological contract breach and violation: A longitudinal study. J. Organ. Behav. 2000, 21, 525–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lu, C.; Siu, O. Job insecurity and job performance: The moderating role of organizational justice and the mediating role of work engagement. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 1249–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyler, T.R.; Blader, S.L. The group engagement model: Procedural justice, social identity, and cooperative behavior. Pers. Soci. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 7, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.T.; Hsieh, H.H. Supervisors as good coaches: Influences of coaching on employees’ in-role behaviors and proactive career behaviors. Int. J. Hum. Res. Manag. 2015, 26, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellinger, A.D.; Ellinger, A.E.; Keller, S.B. Supervisory coaching behavior, employee satisfaction, and warehouse employee performance: A dyadic perspective in the distribution industry. Hum. Res. Dev. Q. 2003, 14, 435–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Lee, C.; Wang, L. Job Insecurity, Knowledge Hiding, And Team Outcomes Paper. In Proceedings of the Academy of Management Conference, Boston, MA, USA, 9–13 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mael, F.; Ashforth, B.E. Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 1992, 13, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, C.R. Identification with multiple targets in a geographically dispersed organization. Manag. Commu. Q. 1997, 10, 491–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dick, R.; van Knippenberg, D.; Kerschreiter, R.; Hertel, G.; Wieseke, J. Interactive effects of work group and organizational identification on job satisfaction and extra-role behavior. J. Voc. Behav. 2008, 72, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, J.E.; Zajac, D.M. A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates, and consequences of organizational commitment. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 108, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.S.; Park, T.Y.; Koo, B. Identifying organizational identification as a basis for attitudes and behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haslam, S.A. Psychology in Organizations; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.J.; Nurunnabi, M.; Kim, T.H.; Kim, T.J. Doing good is not enough, you should have been authentic: The mediating effect of organizational identification, and moderating effect of authentic leadership between csr and performance. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Atwi, A.A.; Bakir, A. Relationships between status judgments, identification, and counterproductive behavior. J. Manag. Psychol. 2014, 29, 472–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marique, G.; Stinglhamber, F. Identification to proximal targets and affective organizational commitment: The mediating role of organizational identification. J. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 10, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, M.R.; Peccei, R. Perceived organizational support, organizational identification, and employee outcomes: Testing a simultaneous multifoci model. J. Pers. Psychol. 2010, 9, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccoli, B.; Callea, A.; Urbini, F.; Chirumbolo, A.; Ingusci, E.; De Witte, H. Job insecurity and performance: The mediating role of organizational identification. Pers. Rev. 2017, 46, 1508–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heslin, P.A.; Vandewalle, D.O.N.; Latham, G.P. Keen to help? Managers’ implicit person theories and their subsequent employee coaching. Pers. Psychol. 2006, 59, 871–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, L.S.; Oades, L.G.; Grant, A.M. Cognitive-behavioral, solution-focused life coaching: Enhancing goal striving, well-being, and hope. J. Posit. Psychol. 2006, 1, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.J. The influence of coaching leadership on safety behavior: The mediating effect of psychological safety and moderating effect of perspective taking. J. Digit. Converg. 2022, 20, 443–451. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraimer, M.L.; Wayne, S.J.; Liden, R.C.; Sparrowe, R.T. The role of job security in understanding the relationship between employees’ perceptions of temporary workers and employees’ performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connelly, C.E.; Černe, M.; Dysvik, A.; Škerlavaj, M. Understanding knowledge hiding in organizations. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 779–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, C.E.; Zweig, D. How perpetrators and targets construe knowledge hiding in organizations. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 24, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.W.; Kim, B.J. The influence of job involvement on knowledge hiding behavior: The mediating effect of knowledge territoriality and the moderating influence of servant leadership. Glob. Bus. Adm. Rev. 2021, 18, 180–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Soc. Methods Res. 1993, 154, 136–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brace, N.; Kemp, R.; Snelgar, R. SPSS for Psychologists: A Guide to Data Analysis using SPSS for Windows, 2nd ed.; Palgrave: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.J. Unstable jobs harm performance: The importance of psychological safety and organizational commitment in employees. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 2158244020920617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Kang, S.W.; Choi, S.B. Effects of employee well-being and self-efficacy on the relationship between coaching leadership and knowledge sharing intention: A study of UK and US employees. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.G.; Kang, S.W.; Choi, S.B. A multilevel study of the relationship between csr promotion climate and happiness at work via organizational identification: Moderation effect of leader–followers value congruence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kipkosgei, F.; Son, S.Y.; Kang, S.W. Coworker trust and knowledge sharing among public sector employees in Kenya. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kipkosgei, F.; Kang, S.W.; Choi, S.B. A team-level study of the relationship between knowledge sharing and trust in Kenya: Moderating role of collaborative technology. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.W. Knowledge withholding: Psychological hindrance to the innovation diffusion within an organisation. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2016, 14, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serenko, A.; Bontis, N. Understanding counterproductive knowledge behavior: Antecedents and consequences of intra-organizational knowledge hiding. J. Knowl. Manag. 2016, 20, 1199–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Percent |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 50.0% |

| Female | 50.0% |

| Age (years) | |

| 20–29 | 15.3% |

| 30–39 | 35.8% |

| 40–49 | 32.7% |

| 50–59 | 16.2% |

| Education | |

| Below high school | 8.7% |

| Community college | 18.8% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 61.6% |

| Graduate degree | 10.9% |

| Position | |

| Staff | 24.3% |

| Assistant manager | 22.3% |

| Manager | 22.5% |

| Deputy general manager | 9.8% |

| Department/general manager | 13.6% |

| Others | 7.5% |

| Tenure (years) | |

| Under 5 | 48.3% |

| 5 to 10 | 25.7% |

| 11 to 15 | 13.9% |

| 16 to 20 | 6.6% |

| 21 to 25 | 2.0% |

| Above 26 | 3.5% |

| Occupation | |

| Office worker | 71.7% |

| Profession (Practitioner) | 7.8% |

| Manufacturing | 6.1% |

| Public official | 5.2% |

| Sales and marketing | 4.6% |

| Administrative positions | 2.9% |

| Education | 0.3% |

| Others | 1.4% |

| Industry type | |

| Manufacturing | 24.6% |

| Wholesale/Retail business | 12.4% |

| Construction | 12.2% |

| Health and welfare | 9.2% |

| Information service and telecommunications | 8.7% |

| Education | 8.1% |

| Services | 6.4% |

| Financial/insurance | 3.5% |

| Consulting and advertising Others | 1.4% |

| Others | 13.5% |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender_T2 | - | ||||||

| 2. Education | −0.12 * | - | |||||

| 3. Tenure_T2 | −0.28 ** | 0.04 | - | ||||

| 4. Position_T2 | −0.40 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.34 ** | - | |||

| 5. Job Insecurity_T1 | −0.05 | −0.02 | −0.02 | 0.17 * | - | ||

| 6. Coaching Leadership_T1 | −0.08 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.10 | −0.14 ** | - | |

| 7. OI_T2 | −0.17 ** | 0.10 | 0.17 ** | 0.19 ** | −0.18 ** | 0.35 ** | - |

| 8. KHB_T3 | −0.12 ** | −0.08 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.24 ** | −0.16 ** | −0.17 ** |

| Model | Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | Total Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Job Insecurity -> Organizational Identificaiton -> Knowledge-Hiding Behavior | 0.222 | −0.026 | 0.248 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeong, J.; Kim, B.-J.; Kim, M.-J. The Impact of Job Insecurity on Knowledge-Hiding Behavior: The Mediating Role of Organizational Identification and the Buffering Role of Coaching Leadership. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16017. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316017

Jeong J, Kim B-J, Kim M-J. The Impact of Job Insecurity on Knowledge-Hiding Behavior: The Mediating Role of Organizational Identification and the Buffering Role of Coaching Leadership. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):16017. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316017

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeong, Jeeyoon, Byung-Jik Kim, and Min-Jik Kim. 2022. "The Impact of Job Insecurity on Knowledge-Hiding Behavior: The Mediating Role of Organizational Identification and the Buffering Role of Coaching Leadership" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 16017. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316017

APA StyleJeong, J., Kim, B.-J., & Kim, M.-J. (2022). The Impact of Job Insecurity on Knowledge-Hiding Behavior: The Mediating Role of Organizational Identification and the Buffering Role of Coaching Leadership. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 16017. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316017