A Study on the Characteristics of Children’s Natural Activities in the Neighborhood and Their Influencing Factors: Evidence from Hangzhou, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Assessment of Children’s Natural Activities in the Neighborhood

1.2. Characteristics of Children’s Natural Activities in the Neighborhood

1.3. Factors Affecting Children’s Natural Activities in the Neighborhood

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Procedures

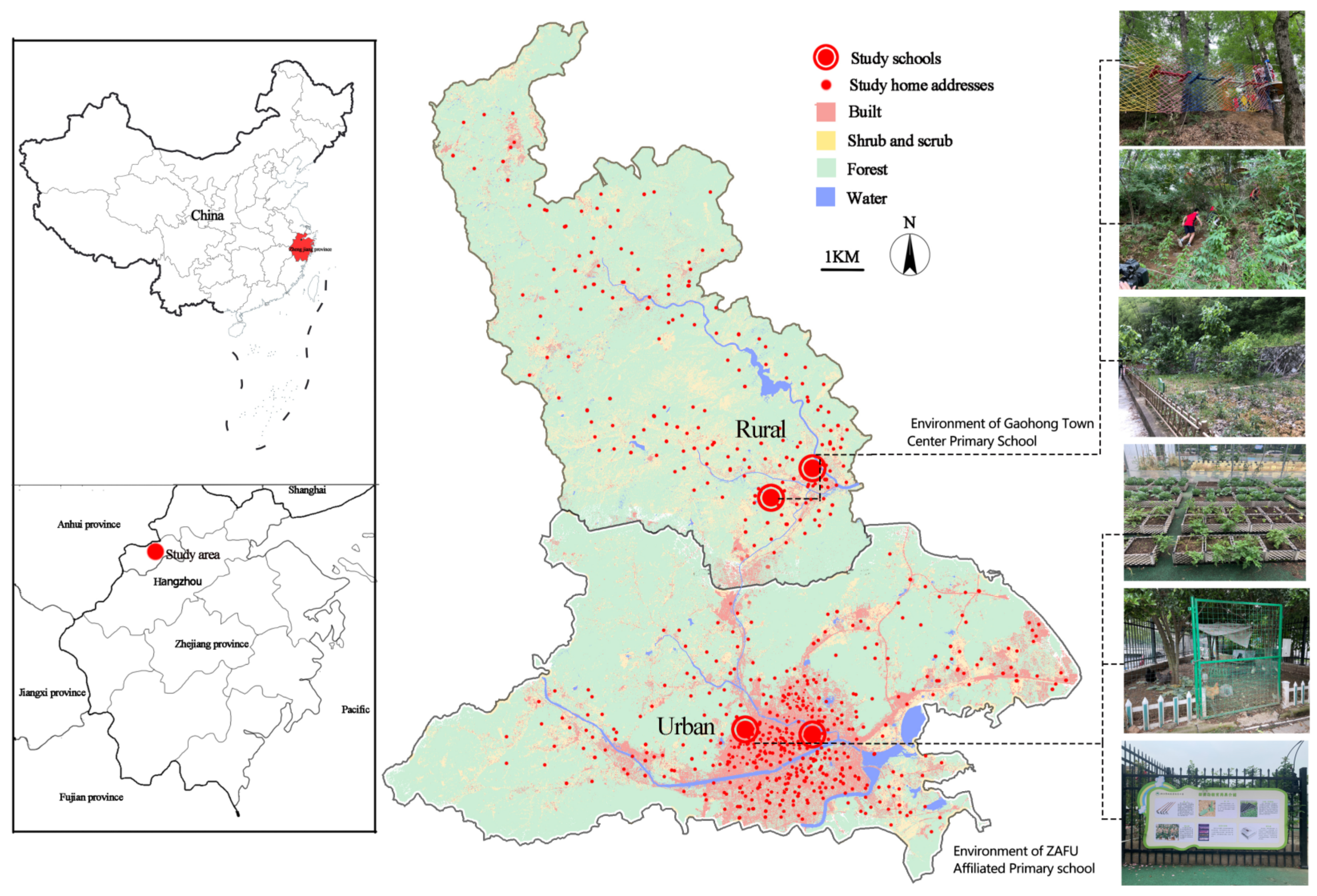

2.2. Study Area

2.3. Participants

2.3.1. Schools

2.3.2. Students

2.4. Questionnaire Procedure

2.5. Questionnaire Design

2.5.1. Basic Information

2.5.2. Children’s Natural Activities in the Neighborhood

2.5.3. Children’s Nature Connectedness

2.5.4. Children’s Environmental Knowledge

2.6. Statistical Analysis Plan

3. Results

3.1. Data Description

3.2. Characteristics of Children’s Natural Activities in the Neighborhood

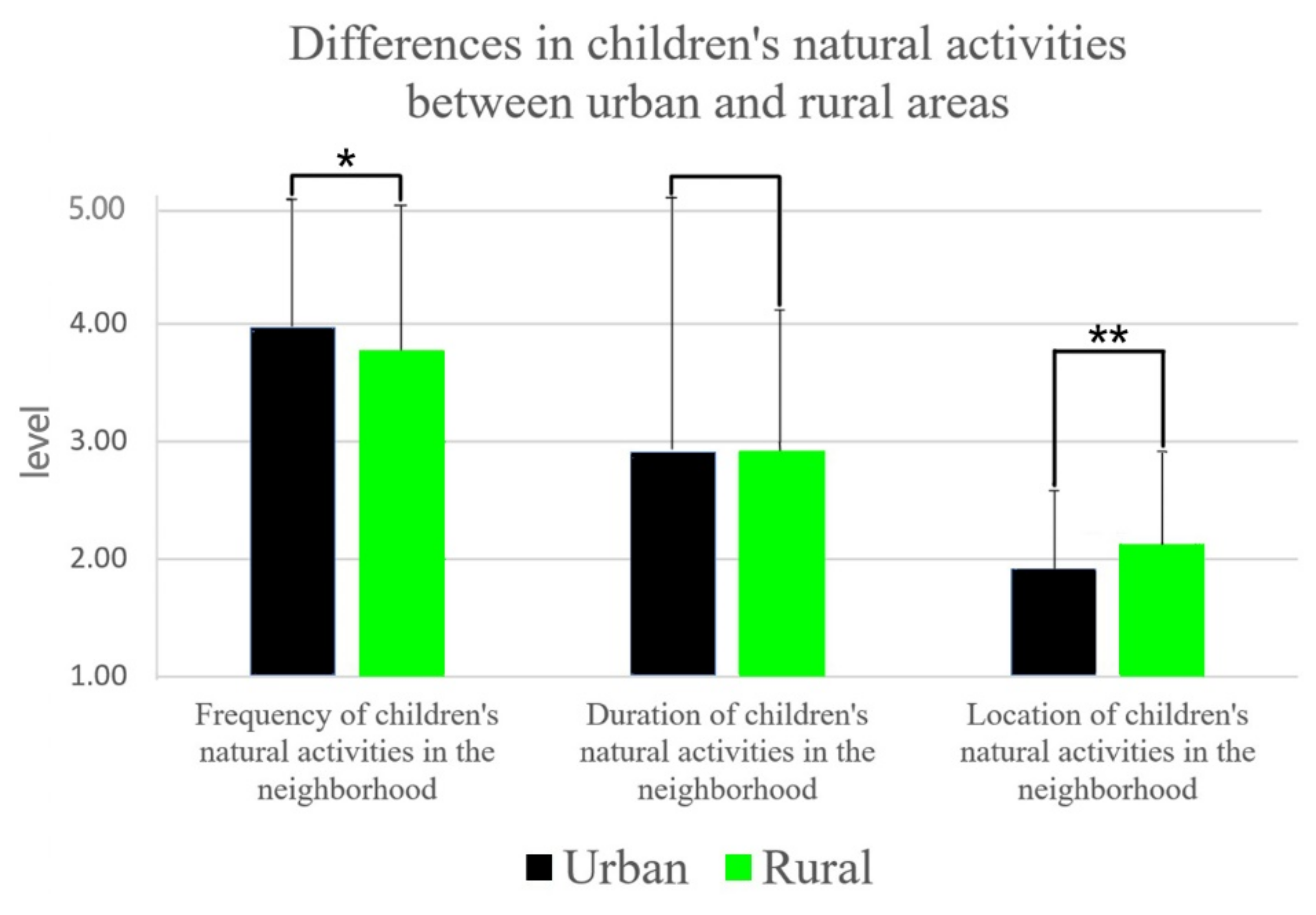

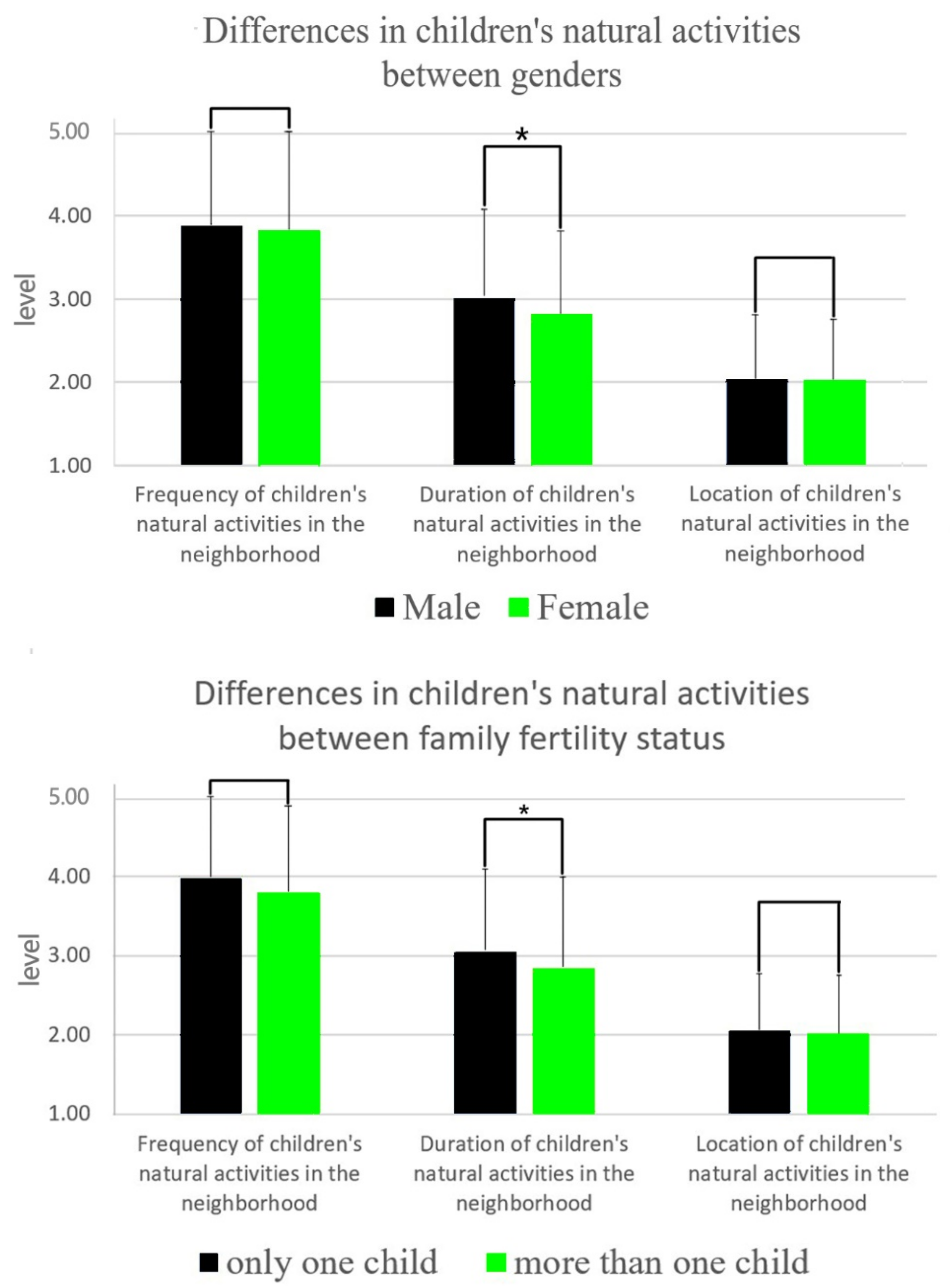

3.3. Factors Affecting Children’s Natural Activities in the Neighborhood

4. Discussion

4.1. Characteristics of Children’s Natural Activities in the Neighborhood

4.2. Impact of Nature Connectedness and Children’s Environmental Knowledge

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Larson, B.M.H.; Fischer, B.; Clayton, S. Should we connect children to nature in the Anthropocene? People Nat. 2021, 4, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaston, K.J.; Soga, M. Extinction of experience: The need to be more specific. People Nat. 2020, 2, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Akasaka, M. Multiple landscape-management and social-policy approaches are essential to mitigate the extinction of experience. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 191, 103634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyle, R. The Thunder Tree: Lessons Froman Urban Wildland; HoughtonMifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, B. The nearby: A scope of seeing. J. Contemp. Chin. Art 2021, 8, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louv, R. Last Child in the Woods: Saving our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder; Algonquin Books: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, R.; Fielding, K.; Nghiem, L.; Chang, C.; Carrasco, L.; Fuller, R. Connection to nature is predicted by family values, social norms and personal experiences of nature. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 28, e01632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colléony, A.; Cohen-Seffer, R.; Shwartz, A. Unpacking the causes and consequences of the extinction of experience. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 251, 108788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, S.; Pensini, P. Nature-based environmental education of children: Environmental knowledge and connectedness to nature, together, are related to ecological behaviour. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2017, 47, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, N.M.; Evans, G.W. Nearby Nature. Environ. Behav. 2003, 35, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitburn, J.; Linklater, W.; Abrahamse, W. Meta-analysis of human connection to nature and proenvironmental behavior. Conserv. Biol. 2019, 34, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCurdy, L.E.; Winterbottom, K.E.; Mehta, S.S.; Roberts, J.R. Using Nature and Outdoor Activity to Improve Children’s Health. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 2010, 40, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Elsadek, M.; Liu, B. Horticultural Activity: Its Contribution to Stress Recovery and Wellbeing for Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, A.; Stewart, D.; Richardson, M.; Hinds, J.; Bragg, R.; White, M.; Burt, J. Monitor of engagement with the natural environment: Developing a method to measure nature connection across the English population (adults and children). In Natural England Commissioned Reports; Natural England: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, T. The benefits of children’s engagement with nature: A systematic literature review. Child. Youth Environ. 2014, 24, 10–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RSPB. Connecting with Nature: Finding out How Connected to Nature the UK’s Children Are. 2013. Available online: www.rspb.org.uk/connectionmeasure (accessed on 1 January 2013).

- United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund. The State of the World’s Children; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, T. Urban Playground: How Child-Friendly Planning and Design Can Save Cities; Riba Publishing: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, A. The Design of Childhood: How the Material World Shapes Independent Kids; Bloomsbury Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Krysiak, N. Designing Child-Friendly High Density Neighbourhoods: Transforming Our Cities for the Health, Wellbeing and Happiness of Children. 2019. Available online: https://www.citiesforplay.com/ (accessed on 1 May 2020).

- Voce, A. Cities Alive: Designing for Urban Childhoods. Child. Youth Environ. 2018, 28, 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holyoak, J. Book Review: Designing Child-Friendly High Density Neighbourhoods. Urban Des. Urban Des. Group J. 2021, 48. Available online: https://www.udg.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/files/UD158_magazine.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Dervo, B.K.; Skår, M.; Köhler, B.; Øian, H.; Vistad, O.I.; Andersen, O.; Gundersen, V. Friluftsliv i Norge anno 2014–Status og Utfordringer; NINA: Oslo, Norway, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Clements, R. An Investigation of the Status of Outdoor Play. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 2004, 5, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Gaston, K.J. Extinction of experience: The loss of human-nature interactions. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 14, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skar, M.; Wold, L.C.; Gundersen, V.; O’Brien, L. Why do children not play in nearby nature? Results from a Norwegian survey. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2016, 16, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Yamanoi, T.; Tsuchiya, K.; Koyanagi, T.F.; Kanai, T. What are the drivers of and barriers to children’s direct experiences of nature? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 180, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MENE. The Department of Environment: Monitor of Engagement with the Natural Environmen. 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/people-and-nature-survey-for-england (accessed on 22 April 2020).

- Van Heel, B.F.; Born, R.J.G.V.D.; Aarts, M.N.C. Everyday childhood nature experiences in an era of urbanisation: An analysis of Dutch children’s drawings of their favourite place to play outdoors. Child. Geogr. 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Yamaura, Y.; Aikoh, T.; Shoji, Y.; Kubo, T.; Gaston, K.J. Reducing the extinction of experience: Association between urban form and recreational use of public greenspace. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 143, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Riveros, R.; Altamirano, A.; De La Barrera, F.; Rozas-Vásquez, D.; Vieli, L.; Meli, P. Linking public urban green spaces and human well-being: A systematic review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 61, 127105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Truong, M.; Nakabayashi, M.; Hosaka, T. How to encourage parents to let children play in nature: Factors affecting parental perception of children’s nature play. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 69, 127497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. The quality–quantity trade-off: Evidence from the relaxation of China’s one-child policy. J. Popul. Econ. 2013, 27, 565–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, V.; Skår, M.; O’Brien, L.; Wold, L.; Follo, G. Children and nearby nature: A nationwide parental survey from Norway. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 17, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, C.; Harvey, C.; Holland, F.; Wall, S. Development and testing of the Nature Connectedness Parental Self-Efficacy (NCPSE) scale. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 65, 127343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brügger, A.; Kaiser, F.G.; Roczen, N. One for All? Eur. Psychol. 2011, 16, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, J.; Kaiser, F.G.; Wilson, M.R. Environmental knowledge and conservation behavior: Exploring prevalence and structure in a representative sample. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2004, 37, 1597–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuttler, S.G.; Stevenson, K.; Kays, R.; Dunn, R.R. Children’s attitudes towards animals are similar across suburban, exurban, and rural areas. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.; Rato, V.; Dabaja, Z.F. Outdoor activities and contact with nature in the Portuguese context: A comparative study between children’s and their parents’ experiences. Child. Geogr. 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Goodale, E.; Chen, J. How contact with nature affects children’s biophilia, biophobia and conservation attitude in China. Biol. Conserv. 2014, 177, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrutia, O.; Ruiz-González, A.; Sanz-Azkue, I.; Díez, J.R. Secondary school students’ familiarity with animals and plants: Hometown size matters. Environ. Educ. Res. 2022, 28, 1564–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, E.; Maguire, S.; Firth, C.; Lumber, R.; Richardson, M.; Young, R. Factors associated with nature connectedness in school-aged children. Curr. Res. Ecol. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 3, 100037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, F.; Barker, J. Commodifying the countryside: The impact of out-of-school care on rural landscapes of children’s play. Area 2001, 33, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X. Is environment ‘a city thing’ in China? Rural–urban differences in environmental attitudes. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, F.; Liu, J.; Zheng, L. The effects of public environmental concern on urban-rural environmental inequality: Evidence from Chinese industrial enterprises. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 80, 103787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.Z.; Moore, R.; Cosco, N. Child-Friendly, Active, Healthy neighborhoods: Physical characteristics and children’s time outdoors. Environ. Behav. 2014, 48, 711–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimann, H.; Björk, J.; Rylander, L.; Bergman, P.; Eiben, G. Neighborhood environment and physical activity among young children: A cross-sectional study from Sweden. Scand. J. Public Health 2015, 43, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loebach, J.E.; Gilliland, J. Free Range Kids? Using GPS-Derived Activity Spaces to Examine Children’s Neighborhood Activity and Mobility. Environ. Behav. 2014, 48, 421–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, L.R.; Cordell, H.K.; Betz, C.J.; Green, G.T. Children’s Time Outdoors: Results from a National Survey. 2011. Available online: http://scholarworks.umass.edu/nerr/2011/Papers/31/ (accessed on 2 August 2016).

- Colléony, A.; Prévot, A.-C.; Jalme, M.S.; Clayton, S. What kind of landscape management can counteract the extinction of experience? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 159, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrus, G.; Scopelliti, M.; Lafortezza, R.; Colangelo, G.; Ferrini, F.; Salbitano, F.; Agrimi, M.; Portoghesi, L.; Semenzato, P.; Sanesi, G. Go greener, feel better? The positive effects of biodiversity on the well-being of individuals visiting urban and peri-urban green areas. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 134, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean | N | SE | Median | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of children’s natural activities in the neighborhood | 3.85 | 767 | 0.04 | 4 | 1–5 |

| Duration of children’s natural activities in the neighborhood | 3 | 767 | 0.07 | 3 | 1–5 |

| Location of children’s natural activities in the neighborhood | 2 | 767 | 0.03 | 2 | 1–3 |

| Children’s nature connectedness | 11 | 767 | 0.04 | 11 | 1–15 |

| Children’s environmental knowledge | 6.58 | 767 | 0.05 | 6 | 1–9 |

| Frequency of Children’s Natural Activities in the Neighborhood | Duration of Children’s Natural Activities in the Neighborhood | Location of Children’s Natural Activities in the Neighborhood | Children’s Nature Connectedness | Children’s Environmental Knowledge | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of children’s natural activities in the neighborhood | Pearson Correlation | 1 | ||||

| Sig. (two-tailed) | ||||||

| Duration of children’s natural activities in the neighborhood | Pearson Correlation | 0.198 ** | 1 | |||

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.000 | |||||

| Location of children’s natural activities in the neighborhood | Pearson Correlation | −0.037 | 0.097 * | 1 | ||

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.360 | 0.017 | ||||

| Children’s nature connectedness | Pearson Correlation | 0.152 ** | 0.015 | 0.099 * | 1 | |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.692 | 0.016 | |||

| Children’s environmental knowledge | Pearson Correlation | 0.030 | 0.072 | 0.163 ** | 0.161 ** | 1 |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.421 | 0.052 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| Residential Area | Gender | Family Fertility Status | Children’s Nature Connectedness | Children’s Environmental Knowledge | R2 | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of children’s natural activities in the neighborhood | 0.04 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.01 * | 0.14 ** | 0.03 | 4.13 ** |

| Duration of children’s natural activities in the neighborhood | −0.01 | 0.08 * | −0.08 * | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 5.25 ** |

| Location of children’s natural activities in the neighborhood | −0.17 ** | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.14 ** | 0.11 ** | 0.07 | 7.16 ** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ji, R.; Li, S.; Shao, Y. A Study on the Characteristics of Children’s Natural Activities in the Neighborhood and Their Influencing Factors: Evidence from Hangzhou, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16087. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316087

Ji R, Li S, Shao Y. A Study on the Characteristics of Children’s Natural Activities in the Neighborhood and Their Influencing Factors: Evidence from Hangzhou, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):16087. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316087

Chicago/Turabian StyleJi, Rui, Sheng Li, and Yuhan Shao. 2022. "A Study on the Characteristics of Children’s Natural Activities in the Neighborhood and Their Influencing Factors: Evidence from Hangzhou, China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 16087. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316087

APA StyleJi, R., Li, S., & Shao, Y. (2022). A Study on the Characteristics of Children’s Natural Activities in the Neighborhood and Their Influencing Factors: Evidence from Hangzhou, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 16087. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316087