Exploring Health Care Professionals’ Perceptions Regarding Shared Clinical Decision-Making in Both Acute and Palliative Cancer Care

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Interview Guide

2.4. Recruitment

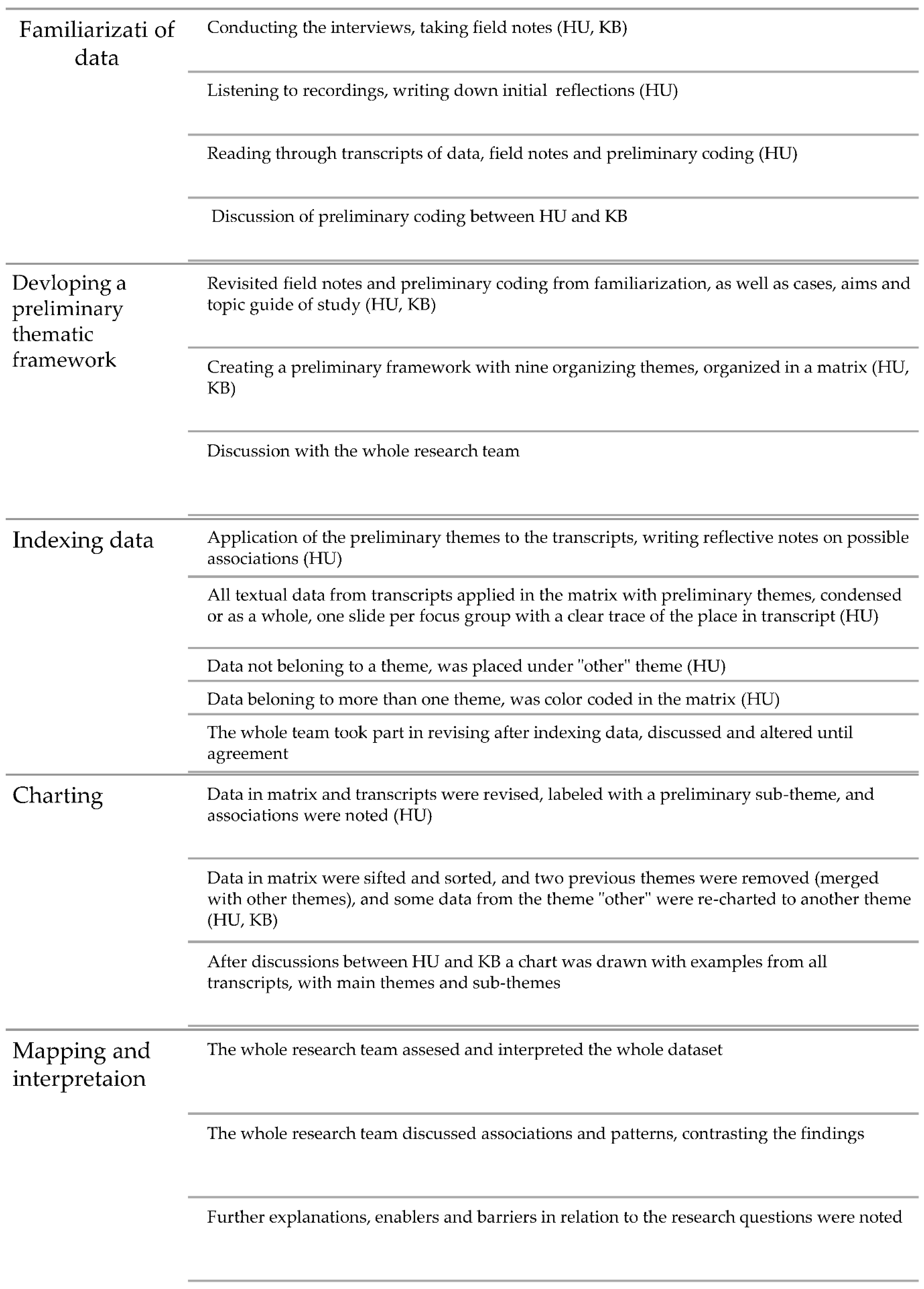

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Uncertainties in Clinical Decision-Making

Organizational Factors Impacting Clinical Decision-Making

“It’s Friday evening and then you cannot expect an assessment by a physician until Monday really, the threshold for sending the patient in is lower, since this is the only way of getting an appropriate assessment.”(FG2, MD2)

“I think we all know that the care is very different between SPC teams. Some does all (assessments, antibiotics) and care for them until they are dying, while others always send in the patients.”(FG5, MD2)

“..This happens all the time- Friday night, because you are perhaps new- it feels stressful when someone cannot breathe properly. You know it may be a pulmonary embolus and there will be a CT (computer tomography). The patient will be admitted and stay over the weekend. Then they lost their place at SPC at home. And then it will be hard to discharge the patient to home.”(FG5, MD1)

“It is frustrating to keep the budget, our ward needs to be fully occupied all the time and when that happens, the patient´s supposed to “choose” another SPC provider. It does matter, it matters a lot. In this case, the patient might end up at a palliative ward somewhere else, making it more difficult for the patients’ family to visit.”(FG3, RN3)

“She is (the patient) still in the care of the oncology clinic even if she doesn´t have active treatment, she still has an appointment there. Here we need to be clear, a clearer decision, SPC is responsible, but the oncology clinic is responsible in one way.”(FG3, RN3)

“They, the oncology clinic should have the difficult conversation. We should not do it for them.”(FG4, RN2)

“during recent years, (...) one doesn’t dare to say no. We are rather thinking, we have a new treatment that possibly could help.”(FG2, MD1)

“Well, now there´s treatment much longer and tougher. Into the last days. I feel the decision is never made, but perhaps close. The difficult conversation doesn’t happen, it is postponed. And then the patient deteriorates and end up like this (admitted to an acute care hospital at EOL).”(FG4, RN2)

“We are spending time ordering scans and tests, but for this kind of patients it is not just a hospitalization, it is a long journey, hours on a stretcher having bone metastasis and pain. It is so much more. We need to have an adequate plan here.”(FG5, MD1)

3.2. Patients and Informal Caregivers’ Prerequisites

“(...), in this case you do know she´s living alone. There is clear inequality for people living alone – they don’t receive support the same way.”(FG1, MD1)

“(…) even if we feel we could handle this at home (for symptom management). We can care for you at home, then this is what will happen, if the patients wish to go to hospital, we cannot say anything else.”(FG1, RN1)

“(…) you can ask the question why the husband wants this. Is it because of the situation at home, that he feels it is too scary for the kids or is it that he wants her to go to the hospital to be cured.”(FG3, RN2)

“Many patients don´t want to go to the hospital, they´ve done it before, they know they are not the top priority at ER, they must wait. But the patient must also be aware of what could happen if not going to the hospital. The patient must be prepared to take the consequences!”(FG4, RN1)

“.. If the patient’s desire is to die at home, the possibility is that this won’t happen, and the patient will die in a hospital instead. (…) this needs to be considered if dying at home is important to her.”(FG5, RN2)

3.3. Balancing the Patients Medical Condition and Needs

“(…) thinking that you can always offer them (the patient/informal caregivers) to go to a hospital for an emergency assessment, and then offer them to come home as soon as possible to assess if this is an acute deterioration that may be treatable or that the patient entered another phase in the disease.”(FG1, RN1)

3.4. Balancing Ethical Dilemmas

“I am thinking of the anxiety of the situation, not to admit her to hospital and risking a dramatic death at home that the children will witness. I feel a lot of stress from this, and I think I would have chosen the “coward” way and admitted her, despite her wishes.”(FG5, MD1)

“Maybe, maybe this new treatment will give an effect. We will see. We will do a new CT in 3 months. Then it is almost impossible for us (SPC at home) to come the next day and say that you are dying. We want to plan for this. That is tough...”(FG2, MD1)

“The consequences of starting too much treatment/diagnostic procedures, that may not lead anywhere, will be that she (the patient) will be in such poor condition. She might die in the hospital (…). Then you won’t be able to support and focus on the husband and the kids’ emotions, you might miss this.”(FG3, RN3)

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Guide (Cases and Questions)

Appendix A.1. Case 1

Appendix A.2. Case 2

Appendix A.3. Suggestions of Questions

(Extra if Needed to the Acute Care Team)

Appendix B

References

- Lundberg, F.E.; Andersson, T.M.L.; Lambe, M.; Engholm, G.; Mørch, L.S.; Johannesen, T.B.; Virtanen, A.; Pettersson, D.; Ólafsdóttir, E.J.; Birgisson, H.; et al. Trends in cancer survival in the Nordic countries 1990–2016: The NORDCAN survival studies. Acta Oncol. 2020, 59, 1266–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanbutsele, G.; Pardon, K.; Van Belle, S.; Surmont, V.; De Laat, M.; Colman, R.; Eecloo, K.; Cocquyt, V.; Geboes, K.; Deliens, L. Effect of early and systematic integration of palliative care in patients with advanced cancer: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. Oncol. 2018, 19, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luta, X.; Maessen, M.; Egger, M.; Stuck, A.E.; Goodman, D.; Clough-Gorr, K.M. Measuring Intensity of End of Life Care: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.; Kin, S.N.Y.; Shum, E.; Wann, A.; Tamjid, B.; Sahu, A.; Torres, J. Anticancer therapy within the last 30 days of life: Results of an audit and re-audit cycle from an Australian regional cancer centre. BMC Palliat Care 2020, 19, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knorrenschild, J.R. When to Stop Oncological Treatment in Palliative Patients—An Increasing Challenge in Times of Immunooncology. Anasthesiol. Intensivmed. Notf. Schmerzther. AINS 2020, 55, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiffen, J.; Corbridge, S.J.; Slimmer, L. Enhancing clinical decision making: Development of a contiguous definition and conceptual framework. J. Prof. Nurs. 2014, 30, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scibetta, C.; Kerr, K.; McGuire, J.; Rabow, M.W. The Costs of Waiting: Implications of the Timing of Palliative Care Consultation among a Cohort of Decedents at a Comprehensive Cancer Center. J. Palliat. Med. 2016, 19, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Kim, S.H.; Roquemore, J.; Dev, R.; Chisholm, G.; Bruera, E. Impact of timing and setting of palliative care referral on quality of end-of-life care in cancer patients. Cancer 2014, 120, 1743–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMartino, L.D.; Weiner, B.J.; Mayer, D.K.; Jackson, G.L.; Biddle, A.K. Do palliative care interventions reduce emergency department visits among patients with cancer at the end of life? A systematic review. J. Palliat. Med. 2014, 17, 1384–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajwah, S.; Oluyase, A.O.; Yi, D.; Gao, W.; Evans, C.J.; Grande, G.; Todd, C.; Costantini, M.; Murtagh, F.E.; Higginson, I.J. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of hospital-based specialist palliative care for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 9, CD012780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eve, A.; Higginson, I.J. Minimum dataset activity for hospice and hospital palliative care services in the UK 1997/98. Palliat. Med. 2000, 14, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schelin, M.E.C.; Sallerfors, B.; Rasmussen, B.H.; Fürst, C.J. Quality of care for the dying across different levels of palliative care development: A population-based cohort study. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 1596–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaasa, S.; Loge, J.H.; Aapro, M.; Albreht, T.; Anderson, R.; Bruera, E.; Brunelli, C.; Caraceni, A.; Cervantes, A.; Currow, D.C.; et al. Integration of oncology and palliative care: A Lancet Oncology Commission. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, e588–e653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuusisto, A.; Santavirta, J.; Saranto, K.; Korhonen, P.; Haavisto, E. Advance care planning for patients with cancer in palliative care: A scoping review from a professional perspective. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 2069–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, J.; Blomberg, C.; Holgersson, G.; Carlsson, T.; Bergqvist, M.; Bergstrom, S. End-of-life care: Where do cancer patients want to die? A systematic review. Asia-Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 13, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinhauser, K.E.; Christakis, N.A.; Clipp, E.C.; McNeilly, M.; Grambow, S.; Parker, J.; Tulsky, J.A. Preparing for the end of life: Preferences of patients, families, physicians, and other care providers. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2001, 22, 727–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westman, B.; Kirkpatrick, L.; Ebrahim, F.; Henriksson, R.; Sharp, L. Patient-reported experiences on supportive care strategies following the introduction of the first Swedish national cancer strategy and in accordance with the new patient act. Acta Oncol. 2018, 57, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancerplan, Stockholm-Gotland 2020–2023. Available online: https://cancercentrum.se/stockholm-gotland/om-oss/strategisk-utvecklingsplan/cancerplan-2020-2023/ (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Westman, B.; Ullgren, H.; Olofsson, A.; Sharp, L. Patient-reported perceptions of care after the introduction of a new advanced cancer nursing role in Sweden. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. Off. J. Eur. Oncol. Nurs. Soc. 2019, 41, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kripalani, S.; LeFevre, F.; Phillips, C.O.; Williams, M.V.; Basaviah, P.; Baker, D.W. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: Implications for patient safety and continuity of care. Jama 2007, 297, 831–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullgren, H. Early palliative care referral, emergency admissions and care transitions- the challenge of integrative care for H&N cancer patients. In Proceedings of the National Conference of Swedish Cancer Nursing Society, Stockholm, Sweden, 27–28 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D.L. Focus Groups as Qualitative Research, 2nd ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, R.; Albrecht, L.; Scott, S.D. Two Approaches to Focus Group Data Collection for Qualitative Health Research: Maximizing Resources and Data Quality. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2018, 17, 1609406917750781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, N.; Bloor, M.; Fischer, J.; Berney, L.; Neale, J. Putting it in context: The use of vignettes in qualitative interviewing. Qual. Res. 2010, 10, 175–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullgren, H.; Sharp, L.; Olofsson, A.; Fransson, P. Factors associated with healthcare utilisation during first year after cancer diagnose-a population-based study. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2020, 30, e13361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullgren, H.; Kirkpatrick, L.; Kilpelainen, S.; Sharp, L. Working in silos?—Head & Neck cancer patients during and after treatment with or without early palliative care referral. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. Off. J. Eur. Oncol. Nurs. Soc. 2017, 26, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullgren, H.; Fransson, P.; Olofsson, A.; Segersvard, R.; Sharp, L. Health care utilization at end of life among patients with lung or pancreatic cancer. Comparison between two Swedish cohorts. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care J. Int. Soc. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, J.; Spencer, L.; O’Connor, W. Carrying Out Qualitative Analysis. In Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers; Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Eds.; SAGE: London, UK, 2003; pp. 219–262. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A.; Burgess, B. Analyzing Qualitative Data; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, D.J.; Furber, C.; Tierney, S.; Swallow, V. Using Framework Analysis in nursing research: A worked example. J. Adv. Nurs. 2013, 69, 2423–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gale, N.K.; Heath, G.; Cameron, E.; Rashid, S.; Redwood, S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, T.L.; Rendle, K.A.; Aakhus, E.; Nimgaonkar, V.; Shah, A.; Bilger, A.; Gabriel, P.E.; Trotta, R.; Braun, J.; Shulman, L.N.; et al. Views from Patients with Cancer in the Setting of Unplanned Acute Care: Informing Approaches to Reduce Health Care Utilization. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2020, 16, e1291–e1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, B.R.; Temel, J.S.; Temin, S.; Alesi, E.R.; Balboni, T.A.; Basch, E.M.; Firn, J.I.; Paice, J.A.; Peppercorn, J.M.; Phillips, T.; et al. Integration of Palliative Care into Standard Oncology Care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 35, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombet, I.; Bouleuc, C.; Piolot, A.; Vilfaillot, A.; Jaulmes, H.; Voisin-Saltiel, S.; Goldwasser, F.; Vinant, P.; Alexandre, J.; Mons, M.; et al. Multicentre analysis of intensity of care at the end-of-life in patients with advanced cancer, combining health administrative data with hospital records: Variations in practice call for routine quality evaluation. BMC Palliat. Care 2019, 18, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Man, Y.; Atsma, F.; Oosterveld-Vlug, M.G.; Brom, L.; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B.D.; Westert, G.P.; Groenewoud, A.S. The Intensity of Hospital Care Utilization by Dutch Patients with Lung or Colorectal Cancer in their Final Months of Life. Cancer Control 2019, 26, 1073274819846574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beans, B.E. Experts Foresee a Major Shift from Inpatient to Ambulatory Care. Pharm. Ther. 2016, 41, 231–237. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, E.A.; Boult, C. Improving the Quality of Transitional Care for Persons with Complex Care Needs. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2003, 51, 556–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, W.; Deliens, L.; Miccinesi, G.; Giusti, F.; Moreels, S.; Donker, G.A.; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B.; Zurriaga, O.; Lopez-Maside, A.; Van den Block, L.; et al. Care provided and care setting transitions in the last three months of life of cancer patients: A nationwide monitoring study in four European countries. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flink, M.; Hesselink, G.; Pijnenborg, L.; Wollersheim, H.; Vernooij-Dassen, M.; Dudzik-Urbaniak, E.; Orrego, C.; Toccafondi, G.; Schoonhoven, L.; Gademan, P.J.; et al. The key actor: A qualitative study of patient participation in the handover process in Europe. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2012, 21 (Suppl. S1), i89–i96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enthoven, A.C. Integrated delivery systems: The cure for fragmentation. Am. J. Manag. Care 2009, 15, S284–S290. [Google Scholar]

- Hirvonen, O.M.; Leskela, R.L.; Gronholm, L.; Haltia, O.; Rissanen, A.; Tyynela-Korhonen, K.; Rahko, E.K.; Lehto, J.T.; Saarto, T. Assessing the utilization of the decision to implement a palliative goal for the treatment of cancer patients during the last year of life at Helsinki University Hospital: A historic cohort study. Acta Oncol. 2019, 58, 1699–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastbom, L.; Milberg, A.; Karlsson, M. ‘We have no crystal ball’—advance care planning at nursing homes from the perspective of nurses and physicians. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 2019, 37, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, B.; Sivo, S.A.; Orlowski, M.; Ford, R.C.; Murphy, J.; Boote, D.N.; Witta, E.L. Qualitative Research via Focus Groups: Will Going Online Affect the Diversity of Your Findings? Cornell Hosp. Q. 2020, 62, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvale, S.; Brinkmann, S. InterViews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2015; p. xviii. 405p. [Google Scholar]

- Peek, L.; Fothergill, A. Using focus groups: Lessons from studying daycare centers, 9/11, and Hurricane Katrina. Qual. Res. 2009, 9, 31–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, S.L.; Bialous, S.; Ben-Gal, Y. The International Society of Nurses in Cancer Care: Position Statements Can Aid Nurses to Think Globally and Act Locally. Oncol. sNurs. Forum 2016, 43, 253–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics of the Participants | N = 22 |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Men | 4 |

| Women | 18 |

| Age groups | |

| 20–40 years | 7 |

| 41–60 years | 15 |

| Profession | |

| Nurse | 14 |

| Physician | 8 |

| Years in profession | |

| 0–5 years | 4 |

| 6–15 years | 11 |

| >15 years | 7 |

| Workplace | |

| SPC at home | 16 |

| Acute cancer care | 6 |

| Specialization | |

| Oncology | 8 |

| Geriatrics and/or palliative care | 1 |

| Not specified | 2 |

| Not specialized | 11 |

| Years at current workplace | |

| 0–5 years | 6 |

| 6–15 years | 13 |

| >15 years | 3 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ullgren, H.; Sharp, L.; Fransson, P.; Bergkvist, K. Exploring Health Care Professionals’ Perceptions Regarding Shared Clinical Decision-Making in Both Acute and Palliative Cancer Care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16134. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316134

Ullgren H, Sharp L, Fransson P, Bergkvist K. Exploring Health Care Professionals’ Perceptions Regarding Shared Clinical Decision-Making in Both Acute and Palliative Cancer Care. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):16134. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316134

Chicago/Turabian StyleUllgren, Helena, Lena Sharp, Per Fransson, and Karin Bergkvist. 2022. "Exploring Health Care Professionals’ Perceptions Regarding Shared Clinical Decision-Making in Both Acute and Palliative Cancer Care" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 16134. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316134

APA StyleUllgren, H., Sharp, L., Fransson, P., & Bergkvist, K. (2022). Exploring Health Care Professionals’ Perceptions Regarding Shared Clinical Decision-Making in Both Acute and Palliative Cancer Care. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 16134. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316134