The Gratitude Resentment and Appreciation Test-Revised Short (GRAT-RS): A Multidimensional Item Response Theory Analysis in Italian Workers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Participants and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

Gratitude Resentment and Appreciation Test-Revised Short (GRAT-RS)—Italian Version

2.3. Data Analysis

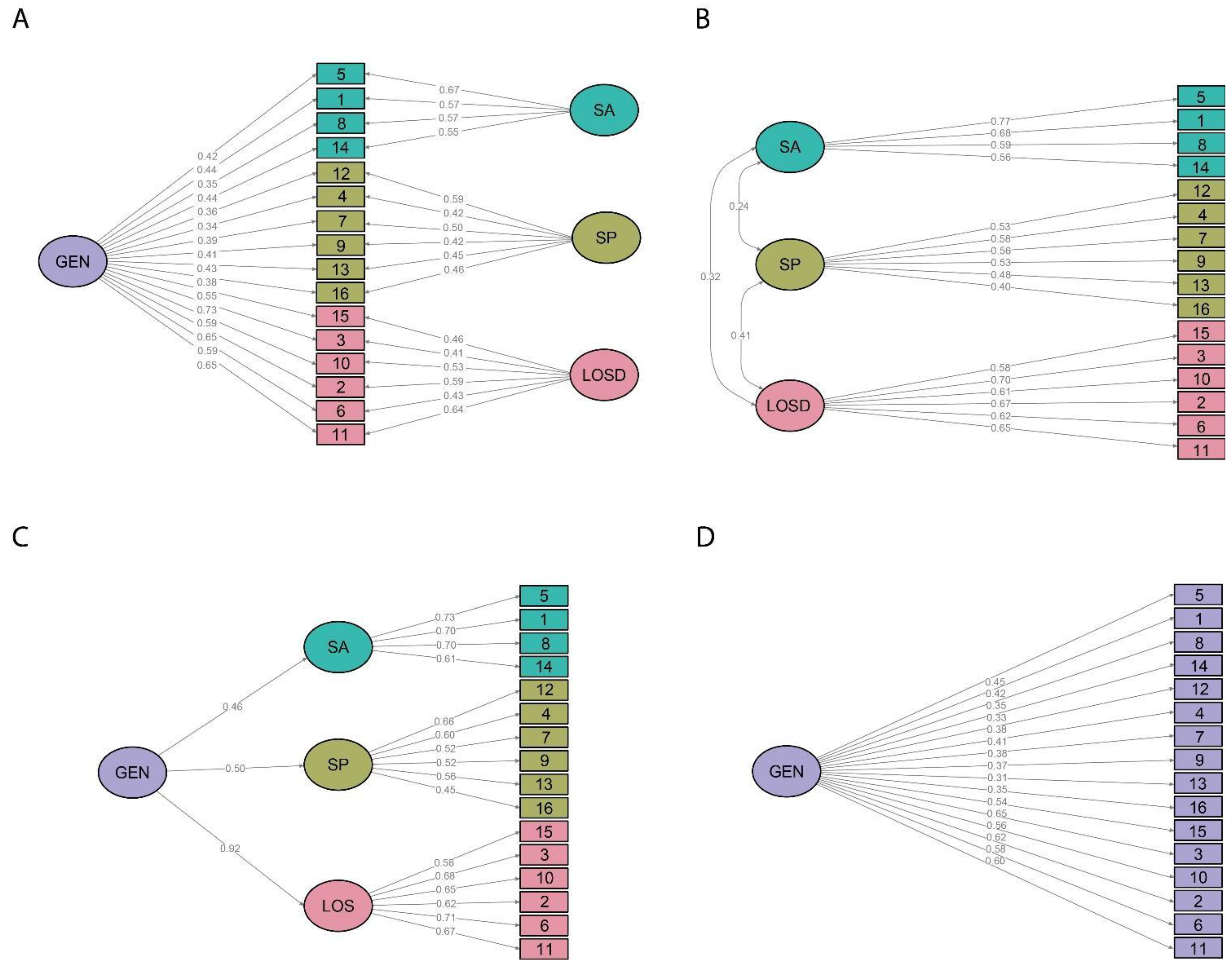

2.3.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

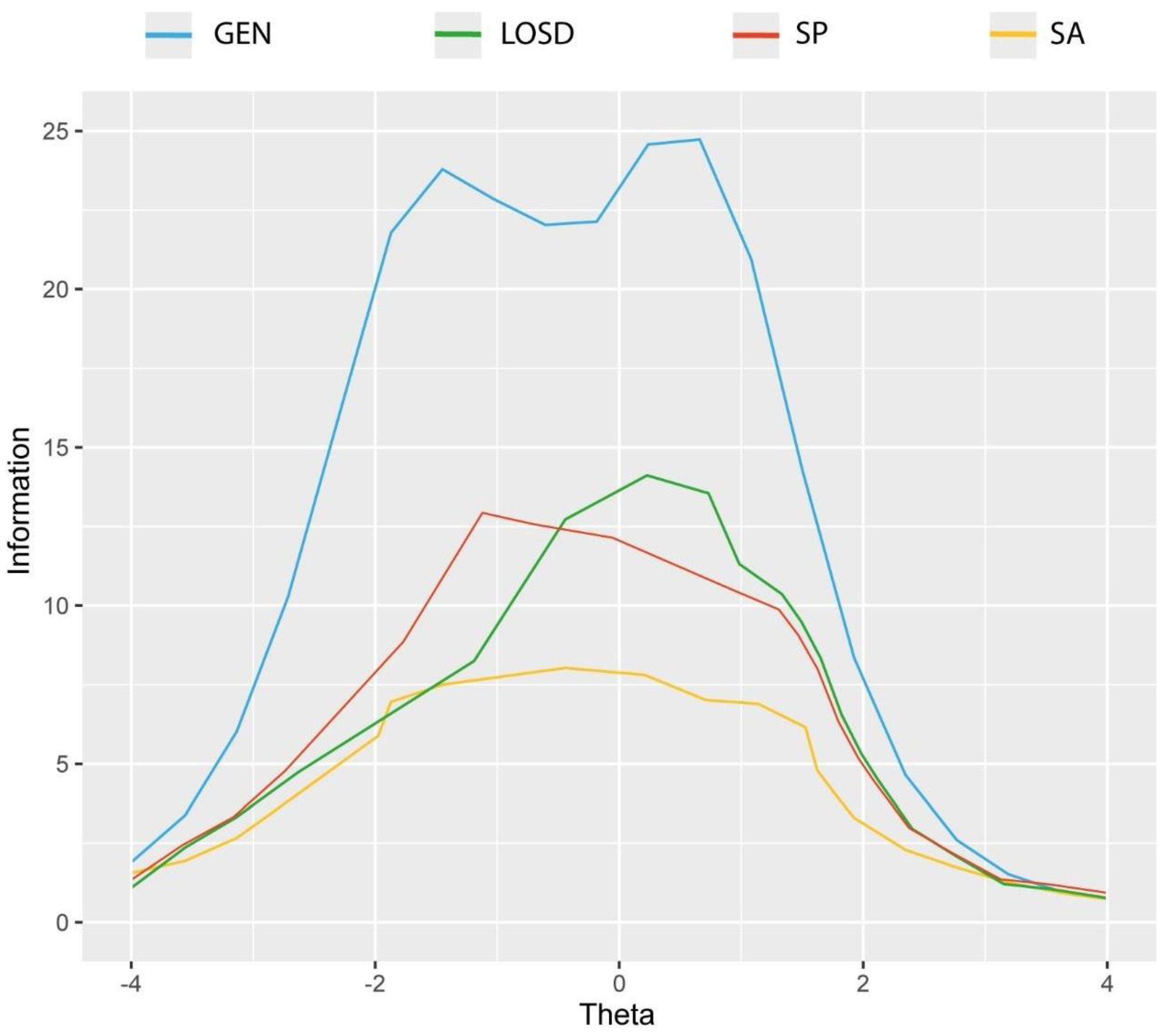

2.3.2. Multidimensional Item Response Theory Analysis

2.3.3. Reliability Analysis

3. Results

| Bifactor | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GEN | LOSD | SP | SA | |

| GRAT-RS Item | λ | λ | λ | λ |

| 2. Life has been good to me. | 0.470 | 0.499 | ||

| 3. There never seems to be enough to go around and I never seem to get my share. | 0.573 | 0.495 | ||

| 6. I really don’t think that I’ve gotten all the good things that I deserve in life. | 0.603 | 0.387 | ||

| 10. More bad things have happened to me in my life than I deserve. | 0.489 | 0.497 | ||

| 11. Because of what I’ve gone through in my life, I really feel like the world owes me something. | 0.683 | 0.453 | ||

| 15. For some reason I don’t seem to get the advantages that others get. | 0.428 | 0.510 | ||

| 4. Oftentimes I have been overwhelmed at the beauty of nature. | 0.396 | 0.528 | ||

| 7. Every Fall I really enjoy watching the leaves change colors. | 0.346 | 0.507 | ||

| 9. I think that it’s important to “Stop and smell the roses”. | 0.405 | 0.390 | ||

| 12. I think that it’s important to pause often to “count my blessings”. | 0.379 | 0.405 | ||

| 13. I think it’s important to enjoy the simple things in life. | 0.373 | 0.619 | ||

| 16. I think it’s important to appreciate each day that you are alive. | 0.339 | 0.590 | ||

| 1. I couldn’t have gotten where I am today without the help of many people. | 0.341 | 0.562 | ||

| 5. Although I think it’s important to feel good about your accomplishments, I think that it’s also important to remember how others have contributed to my accomplishments. | 0.337 | 0.611 | ||

| 8. Although I’m basically in control of my life, I can’t help but think about all those who have supported me and helped me along the way. | 0.363 | 0.682 | ||

| 14. I feel deeply appreciative for the things others have done for me in my life. | 0.339 | 0.718 | ||

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Emmons, R.A.; Shelton, C.M. Gratitude and the science of positive psychology. In Handbook of Positive Psychology; Snyder, C.R., Lopez, S.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 459–471. [Google Scholar]

- Pruyser, P.W. The Minister as Diagnostician: Personal Problems in Pastoral Perspective; Westminster Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S. Emotion and Adaptation; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Lazarus, B.N. Passion and Reason: Making Sense of Our Emotions; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- McCullough, M.E.; Emmons, R.A.; Tsang, J.A. The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.M.; Froh, J.J.; Geraghty, A.W. Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 890–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B. An Attributional Theory of Motivation and Emotion; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, P.C.; Woodward, K.; Stone, T.; Kolts, R.L. Gratitude and happiness: Development of a measure of gratitude, and relationships with subjective well-being. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2003, 31, 431–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Positive psychology, positive prevention, and positive therapy. In Handbook of Positive Psychology; Snyder, C.R., Lopez, S.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M.E.P.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive psychology: An introduction. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, R.A.; McCullough, M.E. Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, S.; Dickerhoof, R.; Boehm, J.K.; Sheldon, K.M. Becoming happier takes both a will and a proper way: An experimental longitudinal intervention to boost well-being. Emotion 2011, 11, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rash, J.A.; Matsuba, M.K.; Prkachin, K.M. Gratitude and well-being: Who benefits the most from a gratitude intervention? Appl. Psychol. 2011, 3, 350–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A.; Saklofske, D.H. The relationship of compassion and self-compassion with personality and emotional intelligence. PAID 40th anniversary special issue. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 169, 110109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hage, S.M.; Romano, J.L.; Conyne, R.K.; Kenny, M.; Matthews, C.; Schwartz, J.P.; Waldo, M. Best practice guidelines on prevention practice, research, training, and social advocacy for psychologists. Couns. Psychol. 2007, 35, 493–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, K.B.; Thoroughgood, C.N.; Stillwell, E.E.; Duffy, M.K.; Scott, K.L.; Adair, E.A. Being present and thankful: A multi-study investigation of mindfulness, gratitude, and employee helping behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 107, 240–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, O.L.; Cooper, C.L.; Phillips, D.R. Intervention studies on enhancing work well-being, reducing burnout, and improving recovery experiences among Hong Kong health care workers and teachers. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2014, 21, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, R.A. Acts of gratitude in organizations. In Positive Organizational Scholarship: Foundations of a New Discipline; Cameron, K.S., Dutton, J.E., Quinn, R.E., Eds.; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: Oakland, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 81–93. [Google Scholar]

- Loi, N.M.; Ng, D.H. The relationship between.gratitude, wellbeing, spirituality, and experiencing meaningful work. Psych 2021, 3, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A.; Blustein, D.L. From Meaning of Working to Meaningful Lives: The Challenges of Expanding Decent Work. Front. Psychol. Organ. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svicher, A.; Gori, A.; Di Fabio, A. Work as Meaning Inventory: A network analysis in Italian workers and students. Aust. J. Career Dev. 2022, 31, 130–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A.; Palazzeschi, L.; Bucci, O. Gratitude in organizations: A contribution for healthy organizational contexts. Front. Psychol. Organ. Psychol. 2017, 8, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A.; Cheung, F.; Peiró, J.-M. Editorial Special Issue Personality and individual differences and healthy organizations. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 166, 11019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L. Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 315–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A.; Peiró, J.M. Human Capital Sustainability Leadership to promote sustainable development and healthy organizations: A new scale. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duradoni, M.; Di Fabio, A. Intrapreneurial Self-Capital and Sustainable Innovative Behavior within Organizations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A.; Svicher, A.; Gori, A. Occupational Fatigue: Relationship with Personality Traits and Decent Work. Front. Psychol. Organ. Psychol. 2021, 12, 3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, J.H.; Brenner, R.E. Disentangling gratitude: A theoretical and psychometric examination of the gratitude resentment and appreciation test–revised short (GRAT–RS). J. Pers. Assess. 2019, 101, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A. Gratitude Resentment and Appreciation Test: Primo contributo alla validazione della versione italiana [Gratitude Resentment and Appreciation Test: First contribution to the validation of the Italian version]. Counseling 2016, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzeschi, A.; Svicher, A.; Gori, A.; Di Fabio, A. Gratitude in organizations: Psychometric properties of the Italian version of the Gratitude Resentment and Appreciation Test–Revised Short (GRAT–RS) in Workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; Watkins, P. Measuring the grateful trait: Development of revised GRAT. In Proceedings of the Annual Convention of the Western Psychological Association, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2 May 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Linden, W.J. (Ed.) Handbook of Item Response Theory; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Embretson, S.E.; Reise, S.P. Item Response Theory for Psychologists; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Reckase, M.D. Multidimensional Item Response Theory Models. In Multidimensional Item Response Theory. Statistics for Social and Behavioral Sciences; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiston, S.C. Accountability Through Action Research: Research Methods for Practitioners. J. Couns. Dev. 1996, 74, 616–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiston, S.C. Selecting career outcome assessments: An organizational scheme. J. Career Assess. 2001, 9, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H. Evaluating the Fit of Structural Equation Models: Tests of Significance and Descriptive Goodness-of-Fit Measures. Methods Psychol. Res. 2003, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Bock, R.D.; Aitkin, M. Marginal maximum likelihood estimation of item parameters: An application of the EM algorithm. Psychometrika 1981, 46, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samejima, F. Estimation of latent ability using a response pattern of graded scores. ETS Res. Bull. Ser. 1968, 1, i-169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, F.B. The Basics of Item Response Theory, 2nd ed.; ERIC Clearinghouse on Assessment and Evaluation: College Park, MD, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Orlando, M.; Thissen, D. Likelihood-based item-fit indices for dichotomous item response theory models. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 2000, 24, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L. Metropolis-Hastings Robbins-Monro algorithm for confirmatory item factor analysis. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 2010, 35, 307–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelleri, J.C.; Jason Lundy, J.; Hays, R.D. Overview of Classical Test Theory and Item Response Theory for the Quantitative Assessment of Items in Developing Patient-Reported Outcomes Measures. Clin. Ther. 2014, 36, 648–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linacre, J.M. Sample size and item calibration stability. Transformation 1994, 7, 66. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, R.P. Test Theory: A Unified Approach; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; Mc Graw Hill.: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R.J. Reliability as a measurement design effect. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2005, 31, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A.; Saklofske, D.H.; Gori, A.; Svicher, A. Perfectionism: A network analysis of relationships between the Big Three dimensions and the Big Five Personality traits. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2022, 199, 111839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.; Robertson, I.; Cooper, C.L. Wellbeing: Productivity and Happiness at Work, 2nd ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Gender | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Male | 279 (52) |

| Female | 258 (48) |

| M (SD) | |

| Age | 45.1 (10.8) |

| GRAT-RS | M (SD) |

| GEN | 154.2 (18.8) |

| LOSD | 63.0 (11.1) |

| SP | 53.3 (8.2) |

| SA | 37.9 (5.9) |

| Models | χ2(df) | CFI | TLI | RMSEA [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bifactor | 161.573 (88) | 0.980 | 0.973 | 0.039 [0.30–0.49] |

| Correlational | 302.369 (101) | 0.945 | 0.935 | 0.061 [0.053–0.069] |

| Higher order | 302.396 (101) | 0.945 | 0.935 | 0.061 [0.053–0.069] |

| Unidimensional | 741.719 (104) | 0.827 | 0.801 | 0.107 [0.100–0.114] |

| GRAT-RS Item | a1 | a2 | a3 | a4 | b1 | b2 | b3 | b4 | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 2 | 1.10 | 1.17 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −1.98 | −0.39 | 2.33 | 4.40 | 0.008 |

| Item 3 | 1.49 | 1.29 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −1.85 | −0.76 | 2.27 | 4.70 | 0.013 |

| Item 6 | 1.47 | 0.94 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −1.73 | −0.42 | 2.71 | 4.91 | 0.000 |

| Item 10 | 1.16 | 1.18 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −2.20 | −0.78 | 2.50 | 4.88 | 0.015 |

| Item 11 | 2.03 | 1.34 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −2.10 | −0.54 | 2.49 | 5.68 | 0.026 |

| Item 15 | 0.98 | 1.16 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −2.00 | −1.09 | 2.16 | 4.70 | 0.030 |

| Item 4 | 0.68 | 0.00 | 1.13 | 0.00 | −3.37 | −0.96 | 2.95 | 4.58 | 0.035 |

| Item 7 | 0.75 | 0.00 | 1.09 | 0.00 | −2.48 | −0.64 | 3.37 | 4.62 | 0.033 |

| Item 9 | 0.83 | 0.00 | 0.80 | 0.00 | −2.78 | −1.12 | 2.62 | 4.60 | 0.000 |

| Item 12 | 0.77 | 0.00 | 0.83 | 0.00 | −2.14 | −1.27 | 2.41 | 4.14 | 0.034 |

| Item 13 | 0.92 | 0.00 | 1.53 | 0.00 | −3.25 | −0.74 | 3.47 | 5.07 | 0.026 |

| Item 16 | 0.79 | 0.00 | 1.37 | 0.00 | −1.69 | −0.40 | 2.94 | 5.23 | 0.023 |

| Item 1 | 0.77 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.27 | −2.39 | −0.04 | 2.07 | 3.92 | 0.000 |

| Item 5 | 0.80 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.45 | −2.17 | −0.02 | 1.60 | 3.82 | 0.000 |

| Item 8 | 0.97 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.83 | −2.15 | −0.15 | 1.93 | 4.32 | 0.005 |

| Item 14 | 0.95 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.01 | −3.03 | −0.48 | 1.51 | 4.22 | 0.000 |

| Reliability | GEN | LOSD | SP | SA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cronbach’s Alpha (a) | 0.85 | 0.89 | 0.80 | 0.87 |

| Omega (ω) | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.83 | 0.87 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Svicher, A.; Palazzeschi, L.; Gori, A.; Di Fabio, A. The Gratitude Resentment and Appreciation Test-Revised Short (GRAT-RS): A Multidimensional Item Response Theory Analysis in Italian Workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16786. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416786

Svicher A, Palazzeschi L, Gori A, Di Fabio A. The Gratitude Resentment and Appreciation Test-Revised Short (GRAT-RS): A Multidimensional Item Response Theory Analysis in Italian Workers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(24):16786. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416786

Chicago/Turabian StyleSvicher, Andrea, Letizia Palazzeschi, Alessio Gori, and Annamaria Di Fabio. 2022. "The Gratitude Resentment and Appreciation Test-Revised Short (GRAT-RS): A Multidimensional Item Response Theory Analysis in Italian Workers" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 24: 16786. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416786

APA StyleSvicher, A., Palazzeschi, L., Gori, A., & Di Fabio, A. (2022). The Gratitude Resentment and Appreciation Test-Revised Short (GRAT-RS): A Multidimensional Item Response Theory Analysis in Italian Workers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), 16786. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416786