Public Health Interventions to Address Housing and Mental Health amongst Migrants from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Backgrounds Living in High-Income Countries: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. General Approach

2.1.1. Identify the Research Question

2.1.2. Identify Relevant Studies

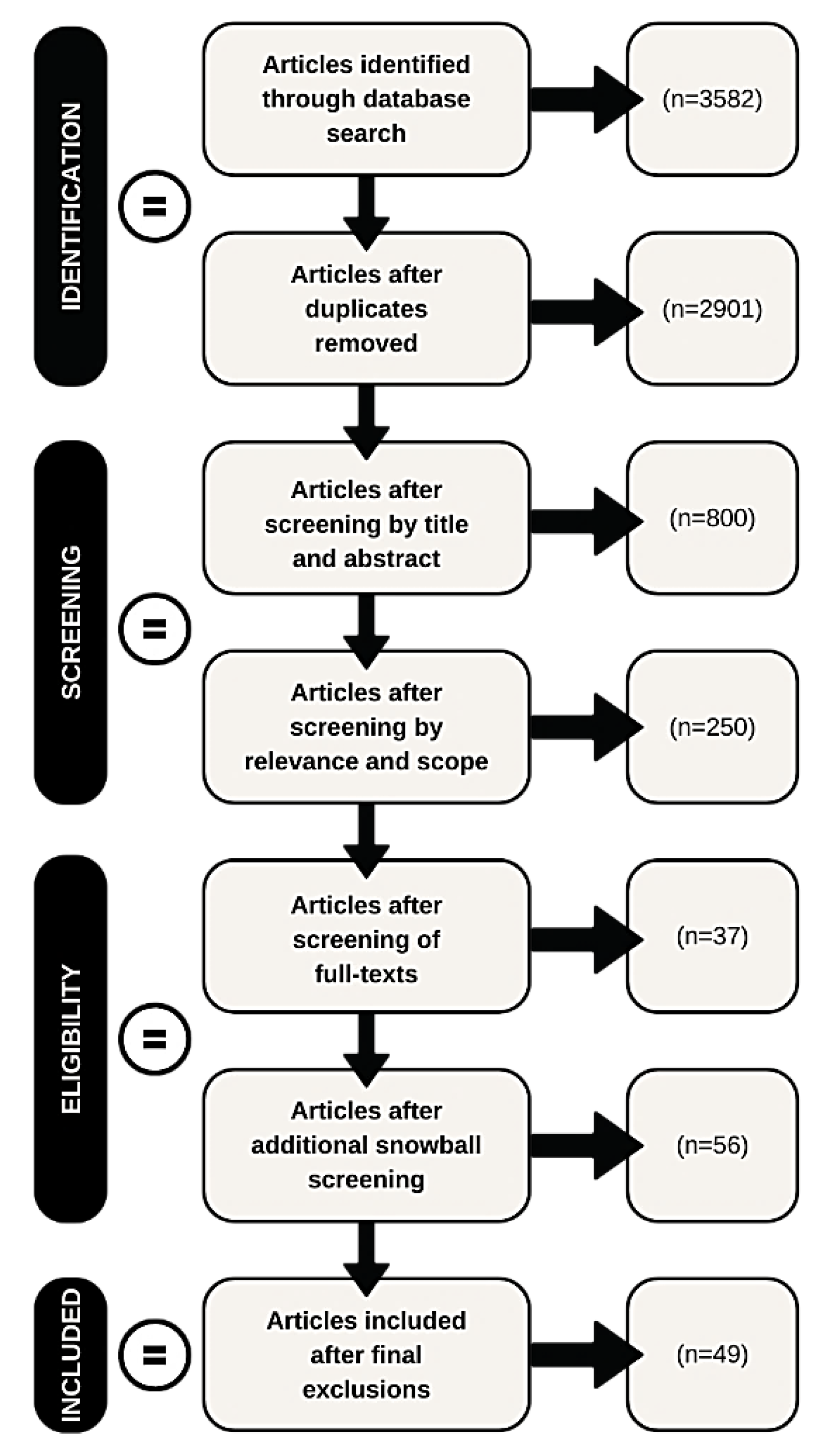

2.1.3. Select Studies

2.1.4. Chart the Data

2.1.5. Collate and Summarize the Data

2.1.6. Consultation

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Intervention Types and Outcomes

3.3. Reporting of Cultural and Linguistic Diversity

3.4. Themes and Sub-Themes

3.5. Housing Provision

3.5.1. Housing First—Efficacy and Considerations

3.5.2. Other Housing Provision Models

3.5.3. Costs of Housing Models

3.5.4. Mental Health—Intersections and Interventions

3.5.5. Housing, Homelessness, and Mental Health

3.5.6. Mental Health Interventions for People Experiencing Homelessness (Non-Housing)

3.5.7. Complexity and Needs beyond Housing

3.5.8. Social Connection and Community

3.5.9. Health and Support Requirements of People Who Are Homeless

3.5.10. Shame, Stigma, and Discrimination

3.5.11. Employment, Financial Assistance, and Income Support

3.5.12. Substance Use

3.5.13. Housing Provision and Substance Use

3.5.14. Substance Use Interventions (Non-Housing)

3.5.15. Service Provider and Policy Issues

3.5.16. System Change

3.5.17. Service Needs and Gaps

3.5.18. The Role of Cultural and Linguistic Diversity

3.5.19. The Intersection of Ethnicity

3.5.20. The Value of Tailored Approaches for People from CaLD Backgrounds

3.5.21. Consumer Experience

3.5.22. Working with People with Lived Experience

3.5.23. Consumer Choice

3.5.24. Novel Ways of Engaging People Vulnerable to or Experiencing Homelessness

4. Discussion

4.1. Housing Is Key but Services to Complement Housing Are Required

4.2. Greater Attention Is Needed toward Indicators of Cultural and Linguistic Identity and Diversity

4.3. Systemic Change Is Vital

5. Strengths and Limitations

5.1. Study Design and Reporting Limitations

5.2. Strengths and Limitations of the Review

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Organization for Migration. Migration Data Portal. Available online: https://migrationdataportal.org/themes/migration-and-health (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- International Organization for Migration. The World Migration Report 2022; IOM: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Migration. The World Migration Report 2020; IOM: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda, H.; Holmes, S.M.; Madrigal, D.S.; Young, M.-E.D.; Beyeler, N.; Quesada, J. Immigration as a Social Determinant of Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2015, 36, 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramage, K.; Vearey, J.; Zwi, A.B.; Robinson, C.; Knipper, M. Migration and health: A global public health research priority. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawes, G.; Gopalkrishnan, N. Far North Queensland Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Communities (CALD) Homelessness Project; James Cook University: Cairns, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fozdar, F.; Hartley, L. Refugee Resettlement in Australia: What We Know and Need to Know. Refug. Surv. Q. 2013, 32, 23–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaleveld, L.; Atkins, M.; Flatau, P. Homelessness in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Populations in Western Australia; Government of Western Australia, Department of Communities: Perth, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wali, N.; Georgeou, N.; Renzaho, A.M.N. ‘Life Is Pulled Back by Such Things’: Intersections Between Language Acquisition, Qualifications, Employment and Access to Settlement Services Among Migrants in Western Sydney. J. Intercult. Stud. 2018, 39, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Migration. Health of Migrants: Resetting the Agenda. In Report of the 2nd Global Consultation; IOM: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Migration. The Health of Migrants: A Core Cross-Cutting Theme (Global Compact Thematic Paper); IOM: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Snapshot of Australia National Summary Data; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2022.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Migration, Australia; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2021.

- Chen, W.; Wu, S.; Ling, L.; Renzaho, A.M. Impacts of social integration and loneliness on mental health of humanitarian migrants in Australia: Evidence from a longitudinal study. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2019, 43, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheath, D.; Flahault, A.; Seybold, J.; Saso, L. Diverse and Complex Challenges to Migrant and Refugee Mental Health: Reflections of the M8 Alliance Expert Group on Migrant Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossin, M.Z. International migration and health: It is time to go beyond conventional theoretical frameworks. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e001938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, R.; Brough, M.; Vromans, L.; Asic-Kobe, M. Mental Health of Newly Arrived Burmese Refugees in Australia: Contributions of Pre-Migration and Post-Migration Experience. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2011, 45, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solar, O.; Irwin, A. A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health. In Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper 2 (Policy and Practice); WHO Document Production Services: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, K.E.; Baker, E.; Blakely, T.; Bentley, R.J. Housing affordability and mental health: Does the relationship differ for renters and home purchasers? Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 94, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, R.; Koplan, C.; Langheim, F.J.P.; Manseau, M.W.; Powers, R.A.; Compton, M.T. The Social Determinants of Mental Health: An Overview and Call to Action. Psychiatr. Ann. 2014, 44, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, A.; Wood, L. Tackling Health Disparities for People Who Are Homeless? Start with Social Determinants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziersch, A.; Walsh, M.; Due, C.; Duivesteyn, E. Exploring the Relationship between Housing and Health for Refugees and Asylum Seekers in South Australia: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.; McKay, F.H.; Lippi, K. Experiences of homelessness by people seeking asylum in Australia: A review of published and “grey” literature. Soc. Policy Adm. 2019, 54, 441–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savic, M.; Chur-Hansen, A.; Mahmood, M.A.; Moore, V.M. ‘We don’t have to go and see a special person to solve this problem’: Trauma, mental health beliefs and processes for addressing ‘mental health issues’ among Sudanese refugees in Australia. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2016, 62, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Migration, Australia, 2017–2018; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2019.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census of Population and Housing: Estimating Homelessness; ABS Cat number 2049.0; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2016.

- Kaleveld, L.; Seivwright, A.; Flatau, P.; Thomas, L.; Bock, C.; Cull, O.; Knight, J. Ending Homelessness in Western Australia 2019 Report; The Western Australian Alliance to End Homelessness Annual Snapshot Report Series; The University of Western Australia, Centre for Social Impact: Perth, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Communities. All Paths Lead to a Home: Western Australia’s 10-Year Strategy on Homelessness 2020–2030; Government of Western Australia, Department of Communities: Perth, Australia, 2020.

- Mental Health Commission. A Safe Place: A Western Australian Strategy to Provide Safe and Stable Accommodation, and Support to People Experiencing Mental Health, Alcohol and Other Drug Issues 2020–2025; Government of Western Australia, Department of Communities: Perth, Australia, 2020.

- Bow, M. Elizabeth Street Common Ground Supportive Housing. Parity 2011, 24, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Multicultural Mental Health Australia. Homelessness Amongst Culturally and Linguistically Diverse People with a Mental Illness: An Australian Study of Industry Perceptions; Australian Government; Department of Health and Aged Care: Canberra, Australia, 2011.

- Flatau, P.; Smith, J.; Carson, G.M.J.; Burvill, A.; Brand, R. The Housing and Homelessness Journeys of Refugees in Australia; AHURI Final Report No. 256; University of Western Australia: Perth, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Couch, J. A new way home: Refugee young people and homelessness in Australia. J. Soc. Incl. 2011, 2, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, J.; Christina, G.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Scoping Reviews. In Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, B.; Yamazaki, R.; Franke, E.; Amanatidis, S.; Ravulo, J.; Steinbeck, K.; Ritchie, J.; Torvaldsen, S. Sustaining dignity? Food insecurity in homeless young people in urban Australia. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2014, 25, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census of Population and Housing: Estimating Homelessness; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2018.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Information Paper—A Statistical Definition of Homelessness; 4922.0; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2012.

- Chamberlin, C.; MacKenzie, D. Counting the Homeless; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2008.

- Deverteuil, G. Survive but not thrive? Geographical strategies for avoiding absolute homelessness among immigrant communities. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2011, 12, 929–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of Multicultural Interests. Implementing the Principles of Multiculturalism Locally: A Planning Guide for Western Australian Local Governments; Government of Western Australia; Office of Multicultural Interests: Perth, Australia, 2010.

- Sharpe, R.A.; Taylor, T.; Fleming, L.E.; Morrissey, K.; Morris, G.; Wigglesworth, R. Making the Case for “Whole System” Approaches: Integrating Public Health and Housing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Research Council (US) and Institute of Medicine. Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders Among Young People; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Universal Health Coverage (UHC); WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. Available online: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Grabowski, D.C. Medicare and Medicaid: Conflicting Incentives for Long-Term Care. Milbank Q. 2007, 85, 579–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The EndNote Team. EndNote; EndNote X9; Clarivate: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Y.; Fazli, G.; Henry, B.; De Villa, E.; Tsamis, C.; Grant, M.; Schwartz, B. The evidence base of primary research in public health emergency preparedness: A scoping review and stakeholder consultation. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qualtrics. Qualtrics, August 2022; Qualtrics: Provo, Utah, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, K.; Brown, P.; Vieira, S. Health, happiness and your future: Using a “men’s group” format to work with homeless men in London. Int. J. Migr. Health Soc. Care 2017, 13, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilkauskas, N.; Michelmore, K. The Effect of the Earned Income Tax Credit on Housing and Living Arrangements. Demography 2019, 56, 1303–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwyer, P.; Brown, D. Accommodating ‘others’? housing dispersed, forced migrants in the UK. J. Soc. Welf. Fam. Law 2008, 30, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gewirtz, A.H.; DeGarmo, D.S.; Plowman, E.J.; August, G.; Realmuto, G. Parenting, parental mental health, and child functioning in families residing in supportive housing. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2009, 79, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulcur, L.; Stefancic, A.; Shinn, M.; Tsemberis, S.; Fischer, S.N. Housing, hospitalization, and cost outcomes for homeless individuals with psychiatric disabilities participating in continuum of care and housing first programmes. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 13, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanrahan, P.; McCoy, M.L.; Cloninger, L.; Dincin, J.; Zeitz, M.A.; Simpatico, T.A.; Luchins, D.J. The mothers’ project for homeless mothers with mental illnesses and their children: A pilot study. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2005, 28, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdie, R.A. Pathways to Housing: The Experiences of Sponsored Refugees and Refugee Claimants in Accessing Permanent Housing in Toronto. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2008, 9, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padgett, D.K.; Gulcur, L.; Tsemberis, S. Housing First Services for People Who Are Homeless with Co-Occurring Serious Mental Illness and Substance Abuse. Res. Soc. Work. Pract. 2006, 16, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutt, R.K.; Hough, R.L.; Goldfinger, S.M.; Lehman, A.F.; Shern, D.L.; Valencia, E.; Wood, P.A. Lessening homelessness among persons with mental illness: A comparison of five randomized treatment trials. Asian J. Psychiatry 2009, 2, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefancic, A.; Tsemberis, S. Housing First for Long-Term Shelter Dwellers with Psychiatric Disabilities in a Suburban County: A Four-Year Study of Housing Access and Retention. J. Prim. Prev. 2007, 28, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsemberis, S.; Eisenberg, R.F. Pathways to Housing: Supported Housing for Street-Dwelling Homeless Individuals with Psychiatric Disabilities. Psychiatr. Serv. 2000, 51, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsemberis, S.; Gulcur, L.; Nakae, M. Housing First, Consumer Choice, and Harm Reduction for Homeless Individuals with a Dual Diagnosis. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenzel, S.L.; D’Amico, E.J.; Barnes, D.; Gilbert, M.L. A Pilot of a Tripartite Prevention Program for Homeless Young Women in the Transition to Adulthood. Women’s Health Issues 2009, 19, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.E.; Malone, D.K.; Clifasefi, S.L. Housing Retention in Single-Site Housing First for Chronically Homeless Individuals With Severe Alcohol Problems. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, S269–S274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmer, T.P.; Stefancic, A.; Ettner, S.L.; Manning, W.G.; Tsemberis, S. Effect of Full-Service Partnerships on Homelessness, Use and Costs of Mental Health Services, and Quality of Life Among Adults with Serious Mental Illness. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2010, 67, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmer, T.P.; Stefancic, A.; Tsemberis, S.; Ettner, S.L. Full-Service Partnerships Among Adults with Serious Mental Illness in California: Impact on Utilization and Costs. Psychiatr. Serv. 2014, 65, 1120–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Slesnick, N.; Feng, X. Housing and Support Services with Homeless Mothers: Benefits to the Mother and Her Children. Community Ment. Health J. 2016, 52, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, T.; Dunton, G.; Henwood, B.; Rhoades, H.; Rice, E.; Wenzel, S. Los Angeles housing models and neighbourhoods’ role in supportive housing residents’ social integration. Hous. Stud. 2019, 34, 609–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padgett, D.K.; Stanhope, V.; Henwood, B.; Stefancic, A. Substance Use Outcomes Among Homeless Clients with Serious Mental Illness: Comparing Housing First with Treatment First Programs. Community Ment. Health J. 2011, 47, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schueller, S.M.; Glover, A.C.; Rufa, A.K.; Dowdle, C.L.; Gross, G.D.; Karnik, N.S.; Zalta, A.K. A Mobile Phone–Based Intervention to Improve Mental Health Among Homeless Young Adults: Pilot Feasibility Trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019, 7, e12347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slesnick, N.; Erdem, G. Efficacy of ecologically-based treatment with substance-abusing homeless mothers: Substance use and housing outcomes. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2013, 45, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slesnick, N.; Guo, X.; Brakenhoff, B.; Bantchevska, D. A Comparison of Three Interventions for Homeless Youth Evidencing Substance Use Disorders: Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2015, 54, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, R.; Rodwin, A.H.; Allcorn, A. Hip Hop, empowerment, and clinical practice for homeless adults with severe mental illness. Soc. Work. Groups 2019, 42, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.; Mares, A.S.; Rosenheck, R.A. Does Housing Chronically Homeless Adults Lead to Social Integration? Psychiatr. Serv. 2012, 63, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, J.S.; D’Amico, E.J.; Ewing, B.A.; Miles, J.N.; Pedersen, E.R. A group-based motivational interviewing brief intervention to reduce substance use and sexual risk behavior among homeless young adults. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2017, 76, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, A.W.; Morocho, C.; Chassler, D.; Sousa, J.; De Jesús, D.; Longworth-Reed, L.; Stewart, E.; Guzman, M.; Sostre, J.; Linsenmeyer, A.; et al. Evaluating culturally and linguistically integrated care for Latinx adults with mental and substance use disorders. Ethn. Health 2019, 27, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenzel, S.L.; Rhoades, H.; LaMotte-Kerr, W.; Duan, L. Everyday discrimination among formerly homeless persons in permanent supportive housing. J. Soc. Distress Homelessness 2019, 28, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winiarski, D.A.; Rufa, A.K.; Bounds, D.T.; Glover, A.C.; Hill, K.A.; Karnik, N.S. Assessing and treating complex mental health needs among homeless youth in a shelter-based clinic. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 109–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adair, C.E.; Streiner, D.L.; Barnhart, R.; Kopp, B.; Veldhuizen, S.; Patterson, M.; Aubry, T.; Lavoie, J.; Sareen, J.; LeBlanc, S.R.; et al. Outcome Trajectories among Homeless Individuals with Mental Disorders in a Multisite Randomised Controlled Trial of Housing First. Can. J. Psychiatry 2017, 62, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aubry, T.; Tsemberis, S.; Adair, C.E.; Veldhuizen, S.; Streiner, D.; Latimer, E.; Sareen, J.; Patterson, M.; McGarvey, K.; Kopp, B.; et al. One-Year Outcomes of a Randomized Controlled Trial of Housing First with ACT in Five Canadian Cities. Psychiatr. Serv. 2015, 66, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubry, T.; Goering, P.; Veldhuizen, S.; Adair, C.E.; Bourque, J.; Distasio, J.; Latimer, E.; Stergiopoulos, V.; Somers, J.; Streiner, D.L.; et al. A Multiple-City RCT of Housing First with Assertive Community Treatment for Homeless Canadians with Serious Mental Illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 2016, 67, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aubry, T.; Bourque, J.; Goering, P.; Crouse, S.; Veldhuizen, S.; Leblanc, S.; Cherner, R.; Bourque, P.; Pakzad, S.; Bradshaw, C. A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of Housing First in a small Canadian City. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, S.W.; Stergiopoulos, V.; O’Campo, P.; Gozdzik, A. Ending homelessness among people with mental illness: The at Home/Chez Soi randomized trial of a Housing First intervention in Toronto. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirst, M.; Zerger, S.; Misir, V.; Hwang, S.; Stergiopoulos, V. The impact of a Housing First randomized controlled trial on substance use problems among homeless individuals with mental illness. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015, 146, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejia-Lancheros, C.; Lachaud, J.; O’Campo, P.; Wiens, K.; Nisenbaum, R.; Wang, R.; Hwang, S.W.; Stergiopoulos, V. Trajectories and mental health-related predictors of perceived discrimination and stigma among homeless adults with mental illness. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Campo, P.; Stergiopoulos, V.; Nir, P.; Levy, M.; Misir, V.; Chum, A.; Arbach, B.; Nisenbaum, R.; To, M.J.; Hwang, S.W. How did a Housing First intervention improve health and social outcomes among homeless adults with mental illness in Toronto? Two-year outcomes from a randomised trial. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palepu, A.; Patterson, M.L.; Moniruzzaman, A.; Frankish, C.J.; Somers, J. Housing First Improves Residential Stability in Homeless Adults with Concurrent Substance Dependence and Mental Disorders. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, e30–e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, M.; Moniruzzaman, A.; Palepu, A.; Zabkiewicz, D.; Frankish, C.J.; Krausz, M.; Somers, J.M. Housing First improves subjective quality of life among homeless adults with mental illness: 12-month findings from a randomized controlled trial in Vancouver, British Columbia. Soc. Psychiatry 2013, 48, 1245–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwan, K.J.; Fallon, B.; Milne, B. “The one thing that actually helps”: Art creation as a self-care and health-promoting practice amongst youth experiencing homelessness. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 93, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers, J.M.; Patterson, M.L.; Moniruzzaman, A.; Currie, L.; Rezansoff, S.N.; Palepu, A.; Fryer, K. Vancouver at Home: Pragmatic randomized trials investigating Housing First for homeless and mentally ill adults. Trials 2013, 14, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers, J.M.; Moniruzzaman, A.; Palepu, A. Changes in daily substance use among people experiencing homelessness and mental illness: 24-month outcomes following randomization to Housing First or usual care. Addiction 2015, 110, 1605–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stergiopoulos, V.; Gozdzik, A.; Misir, V.; Skosireva, A.; Connelly, J.; Sarang, A.; Whisler, A.; Hwang, S.W.; O’Campo, P.; McKenzie, K. Effectiveness of Housing First with Intensive Case Management in an Ethnically Diverse Sample of Homeless Adults with Mental Illness: A Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stergiopoulos, V.; Hwang, S.W.; Gozdzik, A.; Nisenbaum, R.; Latimer, E.; Rabouin, D.; Adair, C.E.; Bourque, J.; Connelly, J.; Frankish, J.; et al. Effect of scattered-site housing using rent supplements and intensive case management on housing stability among homeless adults with mental illness: A randomized trial. JAMA 2015, 313, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stergiopoulos, V.; Gozdzik, A.; Misir, V.; Skosireva, A.; Sarang, A.; Connelly, J.; Whisler, A.; McKenzie, K. The effectiveness of a Housing First adaptation for ethnic minority groups: Findings of a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stergiopoulos, V.; Mejia-Lancheros, C.; Nisenbaum, R.; Wang, R.; Lachaud, J.; O’Campo, P.; Hwang, S.W. Long-term effects of rent supplements and mental health support services on housing and health outcomes of homeless adults with mental illness: Extension study of the At Home/Chez Soi randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 915–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stergiopoulos, V.; O’campo, P.; Gozdzik, A.; Jeyaratnam, J.; Corneau, S.; Sarang, A.; Hwang, S.W. Moving from rhetoric to reality: Adapting Housing First for homeless individuals with mental illness from ethno-racial groups. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanoski, K.; Veldhuizen, S.; Krausz, M.; Schutz, C.; Somers, J.M.; Kirst, M.; Fleury, M.-J.; Stergiopoulos, V.; Patterson, M.; Strehlau, V.; et al. Effects of comorbid substance use disorders on outcomes in a Housing First intervention for homeless people with mental illness: (Alcoholism and Drug Addiction). Addiction 2017, 113, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, J.S.; Aubry, T.; Goering, P.; Adair, C.E.; Distasio, J.; Jette, J.; Nolin, D.; Stergiopoulos, V.; Streiner, D.L.; Tsemberis, S. Tenants with additional needs: When housing first does not solve homelessness. J. Ment. Health 2016, 25, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karim, K.; Tischler, V.; Gregory, P.; Vostanis, P. Homeless Children and Parents: Short-Term Mental Health Outcome. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2006, 52, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute. What is the Housing First Model and How Does It Help Those Experiencing Homelessness? Available online: https://www.ahuri.edu.au/research/brief/what-housing-first-model-and-how-does-it-help-those-experiencing-homelessness (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- United States Interagency Council on Homelessness. Housing First Checklist: Assessing Projects and Systems for a Housing First Orientation; United States Interagency Council on Homelessness: Washington, DC, USA, 2016.

- Tsemberis, S. Housing First: Basic Tenets of the Definition Across Cultures. Eur. J. Homelessness 2012, 6, 169–173. [Google Scholar]

- Rhatigan, N.; Blay, E. Housing First: The Answer to the Question… How do We end Homelessness in 10 Years? Discussion Paper; WA Alliance to End Homelessness: Perth, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, H.; Saad, A.; Magwood, O.; Alkhateeb, Q.; Mathew, C.; Khalaf, G.; Pottie, K. Understanding the health and housing experiences of refugees and other migrant populations experiencing homelessness or vulnerable housing: A systematic review using GRADE-CERQual. CMAJ Open 2021, 9, E681–E692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleace, N.; Quilgars, D. Improving Health and Social Integration through Housing First a Review; The Centre for Housing Policy: York, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bradby, H. Race, ethnicity and health: The costs and benefits of conceptualising racism and ethnicity. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 955–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federation of Ethnic Communities’ Councils of Australia. If We Don’t Count it… It Doesn’t Count! Towards Consistent National Data Collection and Reporting on Cultural, Ethnic and Linguistic Diversity: Issues Paper; Federation of Ethnic Communities Councils of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, R.; Walton, M.; Chitkara, U.; Manias, E.; Chauhan, A.; Latanik, M.; Leone, D. Beyond translation: Engaging with culturally and linguistically diverse consumers. Health Expect. 2020, 23, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minas, H.; Kakuma, R.; Too, L.S.; Vayani, H.; Orapeleng, S.; Prasad-Ildes, R.; Turner, G.; Procter, N.; Oehm, D. Mental health research and evaluation in multicultural Australia: Developing a culture of inclusion. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2013, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, K.; Nebeker, C.; Carpendale, E. Responsibilities for ensuring inclusion and representation in research: A systems perspective to advance ethical practices. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2019, 53, 835–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, K.; Dyb, E.; Knutagard, M.; Novak-Zezula, S.; Trummer, U. Migration and Homelessness: Measuring the Intersections. Eur. J. Homelessness 2020, 14, 13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, K. Racism is the public health crisis. Lancet 2021, 397, 1342–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waite, R.; Sawyer, L.; Waite, D. A call to action for community/public health nurses: Treat structural racism as the critical social determinant of health it is. Public Health Nurs. 2020, 37, 147–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, D.R.; Cooper, L.A. Reducing Racial Inequities in Health: Using What We Already Know to Take Action. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inclusion Criteria |

|---|

| Full text. |

| Quantitative and qualitative primary studies. |

| Peer-reviewed literature. |

| Published between 2000 and 2020. |

| English language. |

| Study intervention: (1) Public health focus and/or address social factors that influence housing (determinants of housing); and (2) Include mental health outcomes such as changes in self-reported mental health, signs, and symptoms of mental health problems. |

| Study population: (1) People from CaLD backgrounds; (2) Over the age of 18 years; (3) Living in high-income countries; (4) Access to a form of basic universal health care; and (5) Vulnerable to homelessness. |

| Migrant | “Immigrant*” OR ethnic OR “Culturally and Linguistically Diverse” OR “Ethnic minority*” OR “migra*” OR “Asylum seeker” OR refugee* |

| Living condition | Homeless* |

| Interventions | intervention* OR strateg* OR “health education” OR “community services” OR “social services” OR housing OR shelter OR “primary health*” OR policy OR evaluat* OR outcome OR impact OR efficacy OR effectiveness |

| Study Type | No. of Studies (%) | Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Randomized control trial | 28 (57.1) | [55,56,60,61,63,68,72,73,76,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99] |

| Longitudinal study | 6 (12.2) | [59,69,75,77,78,100] |

| Qualitative | 5 (10.2) | [54,58,70,74,90] |

| Mixed methods | 3 (6.1) | [52,64,71] |

| Quasi-experimental study | 3 (6.1) | [53,66,67] |

| Retrospective chart review | 1 (2.0) | [57] |

| Comparative study | 1 (2.0) | [62] |

| Cross-sectional evaluation | 1 (2.0) | [79] |

| Non-randomized control trial | 1 (2.0) | [65] |

| TOTAL | 49 (100) |

| Intervention Type | Program | No. of Studies (%) | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Housing and shelter provision | Housing first | 26 (53.0) | [56,59,61,62,63,70,77,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99] |

| Full-service partnership | 2 (4.1) | [66,67] | |

| Ecologically based treatment | 2 (4.1) | [68,72] | |

| Permanent supportive housing | 2 (4.1) | [69,78] | |

| Supportive housing | 1 (2.0) | [55] | |

| Rehousing in the community | 1 (2.0) | [100] | |

| Housing—various | 1 (2.0) | [60] | |

| Collaborative initiative to help end homelessness | 1 (2.0) | [75] | |

| Total | 36 (73.5) | ||

| Physical health including substance use | Thresholds mothers project | 1 (2.0) | [57] |

| Substance use interventions | 1 (2.0) | [73] | |

| AWARE: AOD and health program | 1 (2.0) | [76] | |

| The Power of YOU-AOD and health program | 1 (2.0) | [64] | |

| Casa-care health service | 1 (2.0) | [77] | |

| Total | 5 (10.2) | ||

| Refugee and migration status | Sponsored refugee status | 1 (2.0) | [58] |

| Forced migration status | 1 (2.0) | [54] | |

| Total | 2 (4.1) | ||

| Mental health | Mobile phone-based mental health intervention | 1 (2.0) | [71] |

| Shelter-based mental health clinic | 1 (2.0) | [79] | |

| Total | 2 (4.1) | ||

| Creative arts intervention | Arts-based program | 1 (2.0) | [90] |

| Hip Hop Self-Expression group intervention | 1 (2.0) | [74] | |

| Total | 2 (4.1) | ||

| Income support | Earned income tax credit | 1 (2.0) | [53] |

| Total | 1 (2.0) | ||

| Group intervention | Men’s group | 1 (2.0) | [52] |

| Total | 1 (2.0) | ||

| TOTAL STUDIES | 49 (100.0) |

| A Note on Housing First |

|---|

| Housing First was developed in the 1990s and is a critical policy response in the USA, the UK, Canada, and Europe [101]. It has been suggested that Housing First should be adopted across a community’s entire homelessness response system [102]. Tsembis [103] described Housing First as being two services, housing and support, underpinned by a program philosophy and values [103]. Generally, the model incorporates five broad principles [104], described below by Rhatigan and Blay [104]:

Housing First approaches comprise initiatives that provide housing, either scattered-site or communal/single site implementation [103], with additional “wrap-around” support, for example, to those with mental health and other health conditions as immediate priorities, “without requiring participation in treatment or sobriety as preconditions” [82]. |

| Classification | No. of Studies (%) | Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | 10 (20.4) | [60,62,64,72,80,88,89,92,100] |

| Race/Ethnicity | 9 (18.4) | [53,63,65,66,67,68,70,76,78] |

| Race | 5 (10.2) | [56,59,61,69,75] |

| Ethno-racial status | 4 (8.2) | [82,84,86,99] |

| Ethnicity or Cultural identity; Country of birth | 3 (6.1) | [87,93,97] |

| Migration status; Country of birth/origin. | 3 (6.1) | [52,54,58] |

| No formal classification used | 3 (6.1) | [55,57,74] |

| Race and Ethnicity | 2 (4.1) | [71,79] |

| Ethnicity; Country of birth. | 2 (4.1) | [91,95] |

| Ethno-cultural identity | 1 (2.0) | [83] |

| Racial-ethnic minority status | 1 (2.0) | [81] |

| Ethnic/Cultural background | 1 (2.0) | [90] |

| Ethno-racial minority status | 1 (2.0) | [98] |

| Visible minority; Country of birth | 1 (2.0) | [85] |

| Race/Ethnicity; Country of birth | 1 (2.0) | [94] |

| Ethno-racial status; Country of birth | 1 (2.0) | [96] |

| Race; Latinx status; Ethnic group | 1 (2.0) | [77] |

| TOTAL | 49 (100) |

| Theme | Sub-Themes |

|---|---|

| Housing provision | Housing First: efficacy and considerations |

| Other service provision models | |

| Costs of housing models | |

| Mental health: intersections and interventions | Housing, homelessness, and mental health |

| Mental health interventions for people experiencing homelessness (non-housing) | |

| Complexity and needs beyond housing | Social connection and community |

| Shame/stigma/discrimination | |

| Health and support requirements of homeless populations | |

| Employment, financial assistance, and income support | |

| Substance use | Housing provision and substance use |

| Substance use interventions (non-housing) | |

| Service provider and policy issues | System change |

| Service needs and gaps | |

| The role of cultural and linguistic diversity | The value of tailored approaches for people from CaLD backgrounds |

| The intersection of ethnicity | |

| Consumer experience | Working with people with lived experience |

| Consumer choice | |

| Novel ways of engaging |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Crawford, G.; Connor, E.; McCausland, K.; Reeves, K.; Blackford, K. Public Health Interventions to Address Housing and Mental Health amongst Migrants from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Backgrounds Living in High-Income Countries: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16946. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416946

Crawford G, Connor E, McCausland K, Reeves K, Blackford K. Public Health Interventions to Address Housing and Mental Health amongst Migrants from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Backgrounds Living in High-Income Countries: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(24):16946. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416946

Chicago/Turabian StyleCrawford, Gemma, Elizabeth Connor, Kahlia McCausland, Karina Reeves, and Krysten Blackford. 2022. "Public Health Interventions to Address Housing and Mental Health amongst Migrants from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Backgrounds Living in High-Income Countries: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 24: 16946. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416946

APA StyleCrawford, G., Connor, E., McCausland, K., Reeves, K., & Blackford, K. (2022). Public Health Interventions to Address Housing and Mental Health amongst Migrants from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Backgrounds Living in High-Income Countries: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), 16946. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416946