Motivations Influencing Alipay Users to Participate in the Ant Forest Campaign: An Empirical Study

Abstract

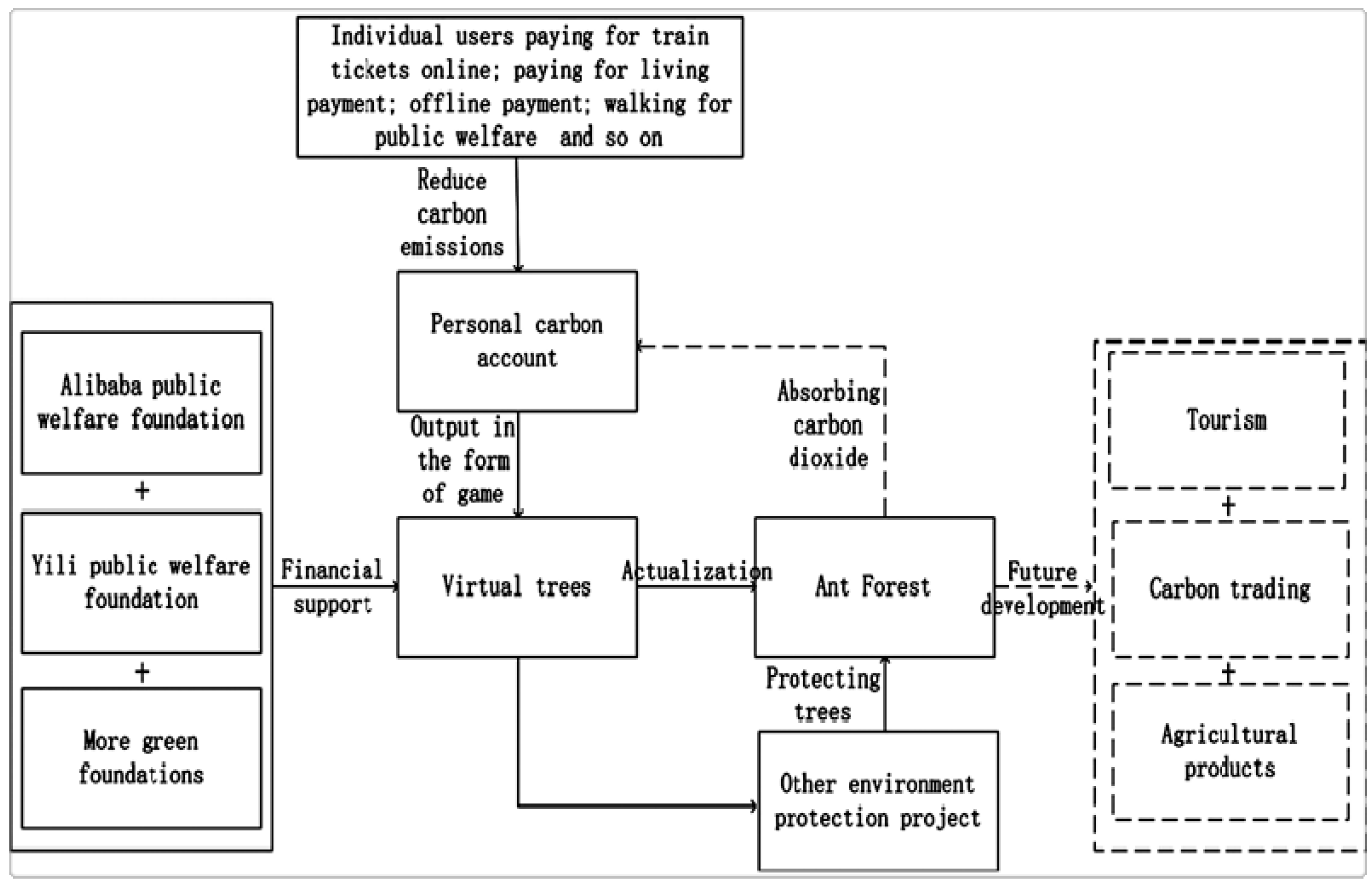

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Mixed Methods

2.2. Research Design for the Quantitative Study

2.3. Research Design for the Qualitative Study

2.4. Ethics Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Study

3.1.1. Demography of the Quantitative Study

3.1.2. Correlation and Multiple Regression Model

3.1.3. Descriptive Statistics of the Survey Results

3.2. Qualitative Study

3.2.1. Intrinsic Motivations

3.2.2. Extrinsic Motivations

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Majeed, M.T.; Mazhar, M.; Sabir, S. Environmental quality and output volatility: The case of South Asian economies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 31276–31288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majeed, M.T.; Ozturk, I. Environmental degradation and population health outcomes: A global panel data analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 15901–15911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.D. Ethical Responsibility towards Environmental Degradation. Indian Philos. Q. 2003, 30, 587–608. [Google Scholar]

- Ajibade, F.O.; Adelodun, B.; Lasisi, K.H.; Fadare, O.O.; Ajibade, T.F.; Nwogwu, N.A.; Wang, A. Environmental pollution and their socioeconomic impacts. In Microbe Mediated Remediation of Environmental Contaminants; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 321–354. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado, R.; Ponce, P.; Criollo, A.; Córdova, K.; Khan, M.K. Environmental degradation and real per capita output: New evidence at the global level grouping countries by income levels. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 189, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazey, P. Approaches to Increasing Desertification in Northern China. Chin. Econ. 2012, 45, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Pan, X.; Wang, D.; Shen, C.; Lu, Q. Combating desertification in China: Past, present and future. Land Use Policy 2013, 31, 311–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Huisingh, D. Combating desertification in China: Monitoring, control, management and revegetation. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Lu, Q.; Wu, B.; Yin, C.; Bao, Y.; Gong, L. Estimation of the Costs of Desertification in China: A Critical Review. Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 975–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Han, L.; Hu, G. Aeolian desertification in China’s northeastern Tibetan Plateau: Understanding the present through the past. Catena 2019, 172, 764–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Peng, Z. Research on Sustainable Development—Take “Ant Forest” for Example. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019; Volume 242, p. 052031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.M.; Zhang, C.X.; Hasi, E.; Dong, Z.B. Has the Three Norths Forest Shelterbelt Program solved the desertification and dust storm problems in arid and semiarid China? J. Arid Environ. 2010, 74, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Zhang, J.; Chen, L.; Zhao, T. Ecosystem water imbalances created during ecological restoration by afforestation in China, and lessons for other developing countries. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 183, 843–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Fu, B.; Wang, S.; Stringer, L.C.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, W. Drivers and impacts of changes in China’s drylands. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 858–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Yun, H.; Yue, H. Spatial Distribution and Dynamic Changes in Research Hotspots for Desertification in China Based on Big Data from CNKI. J. Resour. Ecol. 2019, 10, 692–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Council for International Cooperation on Environment and Development (CCICED) Secretariat. Green Finance. In Green Consensus and High Quality Development; Springer: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z. Saving the Environment by Being “Green” with Fintech: The Contradictions between Environmentalism and Reality in the Case of Ant Forest. Master’s Thesis, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 2018. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/display/289960765 (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Mi, L.; Xu, T.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, J.; Lv, T.; Gan, X.; Shang, K.; Qiao, L. Playing Ant Forest to promote online green behavior: A new perspective on uses and gratifications. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 278, 111544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinese Academy of Cyberspace Studies (Ed.) Benefits of the Internet to the People. In China Internet Development Report 2017; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Feng, Y.; Sun, J.; Yan, J. Motivation Analysis of Online Green Users: Evidence From Chinese “Ant Forest”. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Yao, X. Fueling Pro-Environmental Behaviors with Gamification Design: Identifying Key Elements in Ant Forest with the Kano Model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamborini, R.; Bowman, N.D.; Eden, A.; Grizzard, M.; Organ, A. Defining Media Enjoyment as the Satisfaction of Intrinsic Needs. J. Commun. 2010, 60, 758–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinecke, L.; Vorderer, P.; Knop, K. Entertainment 2.0? The Role of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Need Satisfaction for the Enjoyment of Facebook Use. J. Commun. 2014, 64, 417–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Taylor, L.; Sun, Q. Families that play together stay together: Investigating family bonding through video games. New Media Soc. 2018, 20, 4074–4094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyal, A.W.; Hongzhuan, C.; Gang, C. From Consumer Satisfaction to Recommendation of Mobile App–Based Services: An Overview of Mobile Taxi Booking Apps. SAGE Open 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.-Y. The Mediating Role of Interaction Between Watching Motivation and Flow of Sports Broadcasting in Multi-Channel Network. SAGE Open 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, G.P.L. Cashless China: Securitization of everyday life through Alipay’s social credit system—Sesame Credit. Chin. J. Commun. 2019, 12, 290–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weins, N.W.; Zhu, A.L.; Qian, J.; Seleguim, F.B.; Ferreira, L.D.C. Ecological Civilization in the making: The ‘construction’ of China’s climate-forestry nexus. Environ. Sociol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Teng, X.; Le, Y.; Li, Y. Strategic orientations and responsible innovation in SMEs: The moderating effects of environmental turbulence. Bus. Strategy Environ. Early View 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. Determinants of Consumers Purchase Attitude and Intention Toward Green Hotel Selection. J. China Tour. Res. 2020, 18, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wei, Z.; Song, X.; Na, S.; Ye, J. When does environmental corporate social responsibility promote managerial ties in China? The moderating role of industrial power and market hierarchy. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2020, 26, 642–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.M.; Lo, L.M.; Liu, C.Y.; Liu, C.; Chiou, W.K. The Impact of Social-Support, Self-efficacy and APP on MBI. In Cross-Cultural Design. Applications in Health, Learning, Communication, and Creativity; Rau, P.L., Ed.; HCII 2020. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 12193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderman, E.M. Achievement motivation theory: Balancing precision and utility. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 101864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothe, E.J.; Ling, M.; North, M.; Klas, A.; Mullan, B.; Novoradovskaya, E. Protection motivation theory and pro-environmental behaviour: A systematic mapping review. Aust. J. Psychol. 2019, 71, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L. Intrinsic motivation, extrinsic reinforcement, and inequity. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1972, 22, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreps, D.M. Intrinsic motivation and extrinsic incentives. Am. Econ. Rev. 1997, 87, 359–364. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2950946 (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Gao, B.; Li, Z.; Yan, J. The influence of social commerce on eco-friendly consumer behavior: Technological and social roles. J. Consum. Behav. 2022, 21, 653–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, C.; Harackiewicz, J.M. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation: The Search for Optimal Motivation and Performance; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baygi, A.H.; Ghonsooly, B.; Ghanizadeh, A. Self-Fulfillment in Higher Education: Contributions from Mastery Goal, Intrinsic Motivation, and Assertions. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2017, 26, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kankanhalli, A.; Tan, B.C.Y.; Kwok-Kee, W. Contributing Knowledge to Electronic Knowledge Repositories: An Empirical Investigation. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harackiewicz, J.M.; Elliot, A.J. Achievement goals and intrinsic motivation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 65, 904–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steers, R.M.; Mowday, R.T.; Shapiro, D.L. The Future of Work Motivation Theory. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2004, 29, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-E.; Kim, H.L.; Lee, S. How event information is trusted and shared on social media: A uses and gratification perspective. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2021, 38, 444–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifinedo, P. Applying uses and gratifications theory and social influence processes to understand students’ pervasive adoption of social networking sites: Perspectives from the Americas. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jere, M.G.; Davis, S.V. An application of uses and gratifications theory to compare consumer motivations for magazine and Internet usage among South African women’s magazine readers. S. Afr. Bus. Rev. 2011, 15, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, C.; Hartmann, P.; Apaolaza, V. Gratifications on Social Networking Sites: The Role of Secondary School Students’ Individual Differences in Loneliness. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2019, 57, 58–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, O.M.; Simlinger, R. When function meets emotion, change can happen: Societal value propositions and disruptive potential in fintechs. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2019, 20, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Mixed-method research: Introduction and application. In Handbook of Educational Policy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1999; pp. 455–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habes, M.; Ali, S.; Pasha, S.A. Statistical Package for Social Sciences Acceptance in Quantitative Research: From the Technology Acceptance Model’s Perspective. FWU J. Soc. Sci. 2021, 15, 34–46. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, R. A sequential mixed model research design: Design, analytical and display issues. Int. J. Mult. Res. Approaches 2009, 3, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elareshi, M.; Habes, M.; Al-Tahat, K.; Ziani, A.; Salloum, S.A. Factors affecting social TV acceptance among Generation Z in Jordan. Acta Psychol. 2022, 230, 103730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subedi, D. Explanatory sequential mixed method design as the third research community of knowledge claim. Am. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 4, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Azawei, A.; Alowayr, A. Predicting the intention to use and hedonic motivation for mobile learning: A comparative study in two Middle Eastern countries. Technol. Soc. 2020, 62, 101325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, H.; Duan, X.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, Z. Determinants of consumers’ continuance intention to use dynamic ride-sharing services. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2022, 104, 103201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams-Nwagwu, E.; Adekannbi, J.; Bello, O. Factors influencing use of the internet: A questionnaire survey of the students of University of Ibadan, Nigeria. Electron. Libr. 2009, 27, 718–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, G.; Haolader, F.A.; Muhammad, K. The role of ICT to make teaching-learning effective in higher institutions of learning in Uganda. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2013, 2, 4061–4073. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiao, S.; Zhou, G. User continuance of a green behavior mobile application in China: An empirical study of Ant Forest. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chyi, H.I.; Yang, M.J.; Lewis, S.C.; Zheng, N. Use of and Satisfaction with Newspaper Sites in the Local Market: Exploring Differences between Hybrid and Online-Only Users. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2010, 87, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinecke, L.; Tamborini, R.; Grizzard, M.; Lewis, R.; Eden, A.; Bowman, N.D. Characterizing Mood Management as Need Satisfaction: The Effects of Intrinsic Needs on Selective Exposure and Mood Repair. J. Commun. 2012, 62, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, B.; Hwang, H.-S.; Lee, D. Social media and life satisfaction among college students: A moderated mediation model of SNS communication network heterogeneity and social self-efficacy on satisfaction with campus life. Soc. Sci. J. 2019, 57, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, W.K.; Hsu, S.E.; Liang, Y.C.; Hong, T.H.; Liang, M.L.; Chen, H.; Liu, C. ISDT Case Study of We’ll App for Postpartum Depression Women. In Cross-Cultural Design. Applications in Arts, Learning, Well-Being, and Social Development; HCII 2021. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Rau, P.L.P., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 12772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Chen, H.; Liang, Y.C.; Lin, R.; Chiou, W.K. ISDT Case Study of Loving Kindness Meditation for Flight Attendants. In Cross-Cultural Design. Applications in Arts, Learning, Well-Being, and Social Development; Rau, P.L.P., Ed.; HCII 2021. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 12772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Chen, H.; Zhou, F.; Long, Q.; Wu, K.; Lo, L.-M.; Hung, T.-H.; Liu, C.-Y.; Chiou, W.-K. Positive intervention effect of mobile health application based on mindfulness and social support theory on postpartum depression symptoms of puerperae. BMC Women’s Health 2022, 22, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Hsu, C. Effects of Travel Motivation, Past Experience, Perceived Constraint, and Attitude on Revisit Intention. J. Travel Res. 2009, 48, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellman, S.; Schweda, A.; Varan, D. The Importance of Social Motives for Watching and Interacting with Digital Television. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2010, 52, 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.-W.; Huang, Y.-M.; Wang, Y.-S. Factors Affecting Students’ Continued Usage Intention Toward Business Simulation Games. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2015, 53, 260–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fırat, M.; Kılınç, H.; Yüzer, T.V. Level of intrinsic motivation of distance education students in e-learning environments. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2017, 34, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, M.; Pérez-Orozco, A.; Carvache-Franco, W.; Víquez-Paniagua, A.G.; Carvache-Franco, O. Motivations and their influence on satisfaction and loyalty in eco-tourism: A study of the foreign tourist in Costa Rica. Anatolia 2022, 33, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wethington, E.; McDarby, M.L. Interview methods (structured, semi-structured, unstructured). Encycl. Adulthood Aging 2015, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. FinTech and Green Finance: The Case of Ant Forest in China. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Public Art and Human Development (ICPAHD 2021), Kunming, China, 24–26 December 2021; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 657–661. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S. NGO as Sympathy Vendor or Public Advocate? A Case Study of NGOs’ Participation in Internet Fundraising Campaigns in China. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2022, 1064–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Internet Philanthropy in China; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, P.; Dhir, A.; Chen, S.; Malibari, A.; Almotairi, M. Why do people purchase virtual goods? A uses and gratification (U&G) theory perspective. Telemat. Inform. 2020, 53, 101376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclercq, T.; Poncin, I.; Hammedi, W. The engagement process during value co-creation: Gamification in new product-development platforms. Int. J. Electron. Commun. 2017, 21, 454–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, M.; Zhang, Q.; Zafar, A.U.; Malik, M.; Waheed, A. Understanding Ant Forest continuance: Effects of user experience, personal attributes and motivational factors. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2021, 122, 471–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Kong, X.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Y. Switching to Green Lifestyles: Behavior Change of Ant Forest Users. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Cai, D. Ant forest through the haze: A case study of gamified participatory pro-Environmental communication in China. J 2019, 2, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhu, H. Consumer Response to Perceived Hypocrisy in Corporate Social Responsibility Activities. SAGE Open 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H. Philanthropy on the move: Mobile communication and neoliberal citizenship in China. Commun. Public 2017, 2, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, T.; Li, X. Recoupling Corporate Culture with New Political Discourse in China’s Platform Economy: The Case of Alibaba. Work. Employ. Soc. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-Z.; He, T.-L.; Song, Y.-R.; Yang, Z.; Zhou, R.-T. Factors impacting donors’ intention to donate to charitable crowd-funding projects in China: A UTAUT-based model. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2017, 21, 404–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipahi, E.; Artantaş, E. Building corporate reputation with social media. Bilecik Şeyh Edebali Univ. J. Soc. Sci. 2017, 2, 9–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Profile | Frequency | Percentage (%) | Valid Percent (%) | Cumulative Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 260 | 65.0 | 65.0 | 65.0 |

| Female | 140 | 35.0 | 35.0 | 100.0 |

| Age | ||||

| Below 20 years | 105 | 26.3 | 26.3 | 26.3 |

| 20 to 30 years | 97 | 24.3 | 24.3 | 50.5 |

| 31 to 40 years | 76 | 19.0 | 19.0 | 69.5 |

| 41 to 50 years | 65 | 16.3 | 16.3 | 85.8 |

| Over 50 years | 57 | 14.2 | 14.2 | 100.0 |

| Highest education | ||||

| Primary School | 5 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| High School | 27 | 6.8 | 6.8 | 8.0 |

| Bachelors | 290 | 72.5 | 72.5 | 80.5 |

| Masters | 49 | 12.3 | 12.3 | 92.8 |

| PhD and above | 29 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 100.0 |

| Profession | ||||

| Student | 290 | 72.5 | 72.5 | 72.5 |

| Job Holder | 55 | 13.8 | 13.8 | 86.3 |

| Business | 32 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 94.3 |

| Others | 23 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 100.0 |

| Gender | Age | Education | Profession | Number of Years Engaged with Ant Forest Activities | Level of Satisfaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1 | |||||

| Age | 0.091 | 1 | ||||

| Education | 0.082 | 0.554 ** | 1 | |||

| Profession | 0.097 | 0.531 ** | 0.455 ** | 1 | ||

| Number of years engaged with Ant Forest Activities | 0.007 | −0.007 | −0.073 | −0.047 | 1 | |

| Level of satisfaction | 0.035 | −0.012 | −0.111 * | −0.061 | 0.644 ** | 1 |

| ANOVA a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | p-Value | |

| 1 b | Regression | 161.316 | 5 | 32.263 | 57.383 | 0.000 c |

| Residual | 221.524 | 394 | 0.562 | |||

| Total | 382.840 | 399 | ||||

| Coefficients a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | p-Value | ||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | 0.626 | 0.130 | 4.825 | 0.000 | |

| Gender | 0.047 | 0.052 | 0.035 | 0.907 | 0.365 | |

| Age | 0.034 | 0.036 | 0.047 | 0.941 | 0.347 | |

| Education | −0.088 | 0.050 | −0.083 | −1.757 | 0.080 | |

| Profession | −0.023 | 0.050 | −0.021 | −0.460 | 0.646 | |

| Number of years engaged with Ant Forest Activities | 0.623 | 0.038 | 0.637 | 16.555 | 0.000 | |

| Items | Frequency | Percent (%) | Valid Percent (%) | Cumulative Percent (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enjoyment of Ant Forest | |||||

| Valid | Yes | 335 | 83.8 | 83.8 | 83.8 |

| No | 65 | 16.3 | 16.3 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 400 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Protecting environment is a vital issue for participating in Ant Forest | |||||

| Valid | Yes | 360 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 90.0 |

| No | 40 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 400 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Awareness of environmental degradation is important | |||||

| Valid | Yes | 356 | 89.0 | 89.0 | 89.0 |

| No | 44 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 400 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Users motivated by the social network, cooperation, and community | |||||

| Valid | Yes | 258 | 64.5 | 64.5 | 64.5 |

| No | 142 | 35.5 | 35.5 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 400 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Participating in Ant Forest is a contribution to society | |||||

| Valid | Yes | 386 | 96.5 | 96.5 | 96.5 |

| No | 14 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 400 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Competition of using Ant Forest | |||||

| Valid | Yes | 220 | 55.0 | 55.0 | 55.0 |

| No | 180 | 45.0 | 45.0 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 400 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, S.; Ibrahiem, M.H.; Li, M. Motivations Influencing Alipay Users to Participate in the Ant Forest Campaign: An Empirical Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 17034. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192417034

Wang S, Ibrahiem MH, Li M. Motivations Influencing Alipay Users to Participate in the Ant Forest Campaign: An Empirical Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(24):17034. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192417034

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Shujie, Mohammed Habes Ibrahiem, and Mengyu Li. 2022. "Motivations Influencing Alipay Users to Participate in the Ant Forest Campaign: An Empirical Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 24: 17034. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192417034

APA StyleWang, S., Ibrahiem, M. H., & Li, M. (2022). Motivations Influencing Alipay Users to Participate in the Ant Forest Campaign: An Empirical Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), 17034. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192417034