HIV, Tuberculosis, and Food Insecurity in Africa—A Syndemics-Based Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Information Sources

2.3. Search Strategy

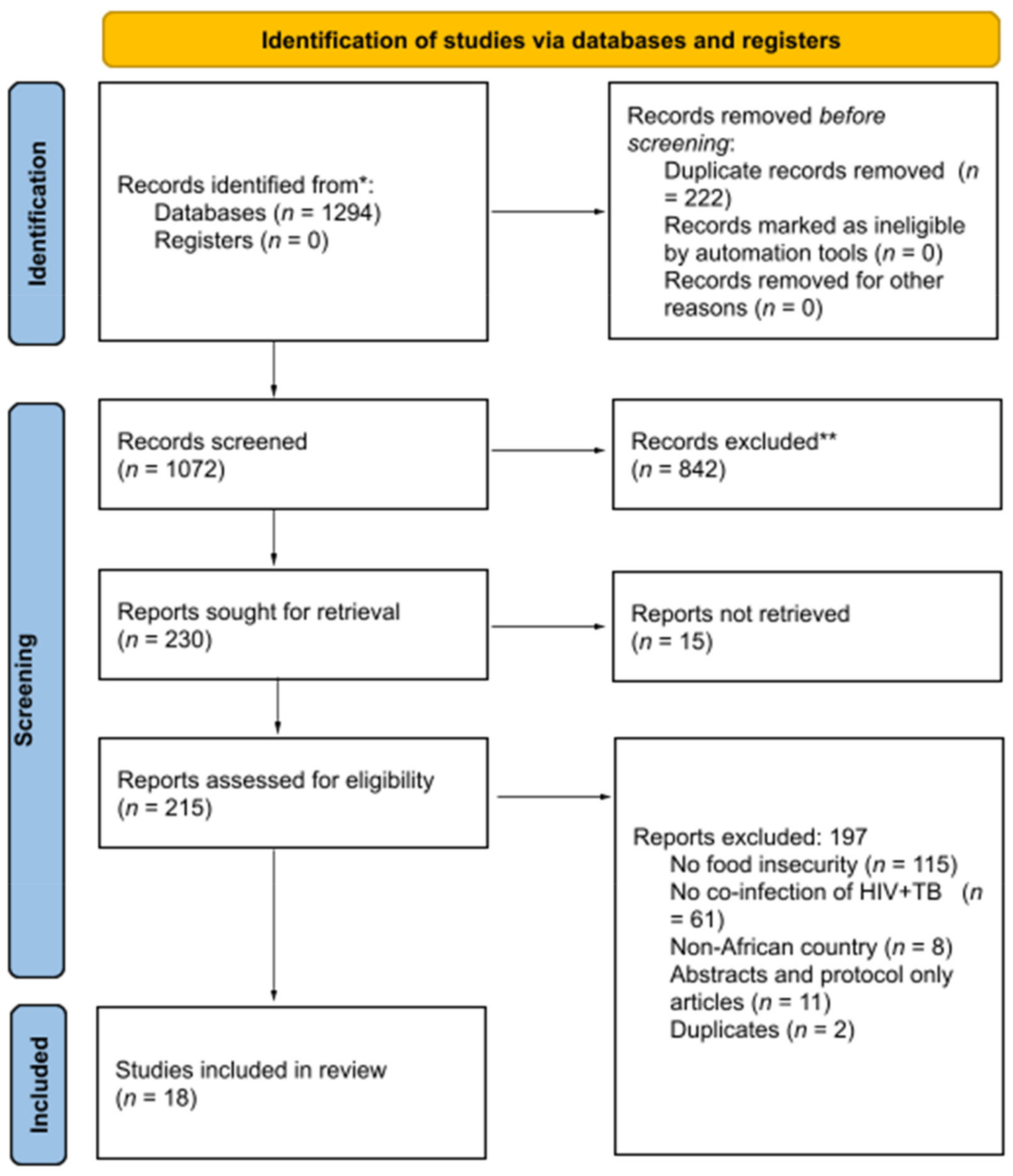

2.4. Selection Process

2.5. Data Collection Process

2.6. Data Items

2.7. Study Risk of Bias Assessment

2.8. Effect Measures

2.9. Synthesis Methods

2.10. Reporting Bias Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Evidence of Food Insecurity in Individuals with HIV/AIDS and TB Co-Infection

3.2. HIV- and TB-Related Outcomes in Co-Infected Individuals

3.3. Treatment Adherence and Health Behaviors in Individuals Co-Infected with HIV and TB

3.4. Economic Drivers of Food Insecurity in HIV/AIDS and TB Co-Infected Individuals in Africa

3.5. Syndemic Coupling Linking Food Insecurity, Other Contextual Factors, and HIV/AIDS and TB Co-Infection in African Settings

3.6. Risk of Bias Assessment

4. Discussion

4.1. Public Health Research and Policy Implications of Syndemic Coupling of HIV/AIDS and TB Co-Infection and Food Insecurity

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

PubMed Full Search Strategy

References

- HIV/AIDS UNPo. UNAIDS DATA 2020; UNAIDS: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2020_aids-data-book_en.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2021).

- World Health Organization. HIV/AIDS. WHO Regional Office for Africa. Published 2021. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/hivaids (accessed on 9 December 2021).

- HIV/AIDS UNPo. UNAIDS DATA 2018; UNAIDS: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/unaids-data-2018_en.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2021).

- World Health Organization. Consolidated Guidelines on the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection 2016 Recommendations for a Public Health Approach; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Consultation on Nutrition and HIV/AIDS in Africa: Evidence, Lessons, and Recommendations for Action. Durban, South Africa; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Nutrition Counselling, Care and Support for HIV-Infected Women; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Paton, N.; Sangeetha, S.; Earnest, A.; Bellamy, R. The impact of malnutrition on survival and the CD4 count response in HIV-infected patients starting antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med. 2006, 7, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Sande, M.A.; van der Loeff, M.F.S.; Aveika, A.A.; Sabally, S.; Togun, T.; Sarge-Njie, R.; Alabi, A.; Jaye, A.; Corrah, T.; Whittle, H. Body mass index at time of HIV diagnosis: A strong and independent predictor of survival. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2004, 37, 1288–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Regional Overview of Food Insecurity-Africa. In African Food Security Prospects Brighter Than Ever; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Nutrient Requirements for People living with HIV/AIDS: Report of a Technical Consultation, 13–15 May 2003; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Nutritional Care and Support for Patients with Tuberculosis; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Studies ACfS. Food Insecurity Crisis Mounting in Africa. Published 2021. Available online: https://africacenter.org/spotlight/food-insecurity-crisis-mounting-africa/ (accessed on 9 December 2021).

- Claros, J.M.; de Pee, S.; Bloem, M.W. Adherence to HIV and TB Care and Treatment, the Role of Food Security and Nutrition. AIDS Behav. 2014, 18, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benzekri, N.A.; Sambou, J.F.; Tamba, I.T.; Diatta, J.P.; Sall, I.; Cisse, O.; Thiam, M.; Bassene, G.; Badji, N.M.; Faye, K.; et al. Nutrition support for HIV-TB co-infected adults in Senegal, West Africa: A randomized pilot implementation study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anema, A.; Vogenthaler, N.; Frongillo, E.; Kadiyala, S.; Weiser, S. Food insecurity and HIV/AIDS: Current knowledge, gaps, and research priorities. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2009, 6, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chop, E.; Duggaraju, A.; Malley, A.; Burke, V.; Caldas, S.; Yeh, P.T.; Narasimhan, M.; Amin, A.; Kennedy, C.E. Food insecurity, sexual risk behavior, and adherence to antiretroviral therapy among women living with HIV: A systematic review. Health Care Women Int. 2017, 38, 927–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jimenez-Sousa, M.A.; Martínez, I.; Medrano, L.M.; Fernandez-Rodriguez, A.; Resino, S. Vitamin D in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection: Influence on Immunity and Disease. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaisson, R.E.; Martinson, N.A. Tuberculosis in Africa—Combating an HIV-Driven Crisis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 1089–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendenhall, E. Syndemics: A new path for global health research. Lancet 2017, 389, 889–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zheng, P.; Fu, H. Prevalence of TB/HIV Co-Infection in Countries Except China: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e64915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2018; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2021; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Tuberculosis (TB). WHO Regional Office for Africa. Published 2021. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/tuberculosis-tb (accessed on 9 December 2021).

- Sharma, S.; Mohan, A.; Kadhiravan, T. HIV-TB co-infection: Epidemiology, diagnosis & management. Indian J. Med. Res. 2005, 121, 550–567. [Google Scholar]

- Macallan, D.C. Malnutrition in tuberculosis. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1999, 34, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, S.; Gupta, H.; Ahluwalia, S. Significance of Nutrition in Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 55, 955–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shetty, N.; Shemko, M.; Vaz, M.; D’Souza, G. An epidemiological evaluation of risk factors for tuberculosis in South India: A matched case control study. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. Off. J. Int. Union Against Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2006, 10, 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Koethe, J.; Reyn, C. Protein-calorie malnutrition, macronutrient supplements, and tuberculosis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2016, 20, 857–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hood, M. A narrative review of recent progress in understanding the relationship between tuberculosis and protein energy malnutrition. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 67, 1122–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; Chou, R.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covidence—Better Systematic Review Management. Covidence. Available online: https://www.covidence.org/ (accessed on 9 December 2021).

- Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (Hfias) for Measurement of Food Access: Indicator Guide|Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance iii Project (FANTA). Available online: https://www.fantaproject.org/monitoring-and-evaluation/household-food-insecurity-access-scale-hfias (accessed on 9 December 2021).

- Knueppel, D.; Demment, M.; Kaiser, L. Validation of the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale in rural Tanzania. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RoB 2: A Revised Cochrane Risk-of-Bias Tool for Randomized Trials. Available online: https://methods.cochrane.org/bias/resources/rob-2-revised-cochrane-risk-bias-tool-randomized-trials (accessed on 9 December 2021).

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, G.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Clin. Epidemiol. Program. 2003. Available online: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 9 December 2021).

- Critical-Appraisal-Tools—Critical Appraisal Tools; Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia. Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 9 December 2021).

- Brice, R. Casp Checklists. CASP—Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Web Site. Available online: https://casp-uk.b-cdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2021).

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakari, M.; Wamsele, J.; MacKenzie, T.; Maro, I.; Kimario, J.; Ali, S.; Dowla, S.; Hendricks, K.; Lukmanji, Z.; Neke, N.M.; et al. Nutritional status of HIV-infected women with tuberculosis in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Public Health Action 2013, 3, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bongongo, T.; van der Heever, H.; Nzaumvila, D.; Saidiya, C. Influence of patients’ living conditions on tuberculosis treatment outcomes in a South African health sub-district. S. Afr. Fam. Pract. 2020, 62, e1–e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, S.J.; Lass, E.; Thistle, P.; Katumbe, L.; Jetha, A.; Schwarz, D.; Bolotin, S.; Barker, R.D.; Simor, A.; Silverman, M. Increased Incidence of Tuberculosis in Zimbabwe, in Association with Food Insecurity, and Economic Collapse: An Ecological Analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e83387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chileshe, M.; Bond, V. Barriers and outcomes: TB patients co-infected with HIV accessing antiretroviral therapy in rural Zambia. AIDS Care 2010, 22 (Suppl. 1), 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chintu, C.; Luo, C.; Bhat, G.; DuPont, H.L.; Mwansa-Salamu, P.; Kabika, M.; Zumla, A. Impact of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type-1 on Common Pediatric Illnesses in Zambia. J. Trop. Pediatr. 1995, 41, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebremichael, D.Y.; Hadush, K.T.; Kebede, E.M.; Zegeye, R.T. Food Insecurity, Nutritional Status, and Factors Associated with Malnutrition among People Living with HIV/AIDS Attending Antiretroviral Therapy at Public Health Facilities in West Shewa Zone, Central Ethiopia. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1913534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hanifa, Y.; Silva, S.; Karstaedt, A.; Sahid, F.; Charalambous, S.; Chihota, V.N.; Churchyard, G.J.; von Gottberg, A.; McCarthy, K.; Nicol, M.P.; et al. What causes symptoms suggestive of tuberculosis in HIV-positive people with negative initial investigations? Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2019, 23, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, P.; Zulu, I.; Amadi, B.; Munkanta, M.; Banda, J.; Rodrigues, L.C.; Mabey, D.; Feldman, R.; Farthing, M.J. Morbidity and nutritional impairment in relation to CD4 count in a Zambian population with high HIV prevalence. Acta Trop. 2002, 83, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaCourse, S.M.; Chester, F.M.; Preidis, G.A.; McCrary, L.M.; Arscott-Mills, T.; Maliwichi, M.; James, G.; McCollum, E.D.; Hosseinipour, M.C. Use Of Xpert For The Diagnosis Of Pulmonary Tuberculosis In Severely Malnourished Hospitalized Malawian Children. Pediatric Infect. Dis. J. 2014, 33, 1200–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Madebo, T.; Nyæster, G.; Lindtjørn, B. HIV Infection and Malnutrition Change the Clinical and Radiological Features of Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 1997, 29, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meressa, D.; Hurtado, R.; Andrews, J.; Diro, E.; Abato, K.; Daniel, T.; Prasad, P.; Prasad, R.; Fekade, B.; Tedla, Y.; et al. Achieving high treatment success for multidrug-resistant TB in Africa: Initiation and scale-up of MDR TB care in Ethiopia—An observational cohort study. Thorax 2015, 70, 1181–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mupere, E.; Parraga, I.; Tisch, D.; Mayanja-Kizza, H.; Whalen, C. Low nutrient intake among adult women and patients with severe tuberculosis disease in Uganda: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mupere, E.; Malone, L.; Zalwango, S.; Chiunda, A.; Okwera, A.; Parraga, I.; Stein, C.M.; Tisch, D.J.; Mugerwa, R.; Boom, W.H.; et al. Lean tissue mass wasting is associated with increased risk of mortality among women with pulmonary tuberculosis in urban Uganda. Ann. Epidemiol. 2012, 22, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rudolph, M.; Kroll, F.; Beery, M.; Marinda, E.; Sobiecki, J.F.; Douglas, G.; Orr, G. A Pilot Study Assessing the Impact of a Fortified Supplementary Food on the Health and Well-Being of Crèche Children and Adult TB Patients in South Africa. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55544. [Google Scholar]

- Sattler, F.; Chelliah, D.; Wu, X.; Sanchez, A.; Kendall, M.A.; Hogg, E.; Lagat, D.; Lalloo, U.; Veloso, V.; Havlir, D.V.; et al. Biomarkers Associated with Death After Initiating Treatment for Tuberculosis and HIV in Patients with Very Low CD4 Cells. Pathog. Immun. 2018, 3, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schacht, C.; Mutaquiha, C.; Faria, F.; Castro, G.; Manaca, N.; Manhiça, I.; Cowan, G.F. Barriers to access and adherence to tuberculosis services, as perceived by patients: A qualitative study in Mozambique. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, Q.; Dima, M.; Ho-Foster, A.; Molebatsi, K.; Modongo, C.; Zetola, N.M.; Shin, S.S. The association of household food insecurity and HIV infection with common mental disorders among newly diagnosed tuberculosis patients in Botswana. Public Health Nutr. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razzouk, D. Burden and Indirect Costs of Mental Disorders. In Mental Health Economics: The Costs and Benefits of Psychiatric Care; Razzouk, D., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 381–391. [Google Scholar]

- Sabariego, C.; Miret, M.; Coenen, M. Global Mental Health. In Mental Health Economics: The Costs and Benefits of Psychiatric Care; Razzouk, D., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 365–379. [Google Scholar]

- Mendenhall, E.; Kohrt, B.A.; Norris, S.A.; Ndetei, D.; Prabhakaran, D. Non-communicable disease syndemics: Poverty, depression, and diabetes among low-income populations. Lancet 2017, 389, 951–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kendall, A.; Olson, C.M.; Frongillo, E.A., Jr. Validation of the Radimer/Cornell measures of hunger and food insecurity. J. Nutr. 1995, 125, 2793–2801. [Google Scholar]

- National NCD MAP. Available online: https://apps.who.int/ncd-multisectoral-plantool/index.html (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Hickey, M.D.; Odeny, T.A.; Petersen, M.; Neilands, T.B.; Padian, N.; Ford, N.; Matthay, Z.; Hoos, D.; Doherty, M.; Beryer, C.; et al. Specification of implementation interventions to address the cascade of HIV care and treatment in resource-limited settings: A systematic review. Implement. Sci. 2017, 12, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Author (Year) | Location/Setting and Population | Study Objective | Study Duration (months) | Total Sample Size | Number of Patients with HIV and TB Co-Infection | Study Design | Delivery/Administration Method | Primary Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bakari et al. (2013) [41] | Location: Urban primary health center in Tanzania Population: Adult women | “Determine the prevalence of low BMI in co-infected TB-HIV women Quantify specific deficits in energy and protein intake Assess food insecurity Assess changes in nutritional status during treatment”. | 12 | 43 | 43 | Pre–post anti-TB treatment study | Research staff | “HIV-positive women with TB have substantial 24-h deficits in energy and protein intake, report significant food insecurity and gain minimal weight on anti-tuberculosis treatment”. |

| Benzekri et al. (2019) [14] | Location: Urban hospitals in Senegal Population: Adults | “Compare the feasibility, acceptability, and potential impact of implementing two different forms of nutrition support for HIV-TB co-infected adults”. | 13 | 26 | 26 | Randomized controlled trial | Nurses, physicians, non-healthcare individuals | “Temporary nutrition support during the critical months of treatment against active TB, could contribute to improved adherence and treatment completion, and subsequently, improved clinical and socioeconomic outcomes”. |

| Bongongo et al. (2020) [42] | Location: Sub-district community-level hospitals in South Africa Population: Adults | “Determine the influence of patients’ living conditions on TB treatment outcomes”. | Not stated | 180 | 83 | Cross-sectional study | Research staff | “Tuberculosis treatment outcomes showed very little difference between where food security was and where there was little or no food security. This survey shows a high death rate (26.5%) and also a high default rate (31.3%) amongst TB respondents that are HIV-positive”. |

| Burke et al. (2014) [43] | Location: Hospitals in rural settings in Zimbabwe Population: Adults and children | Authors hypothesized that in the setting of high HIV prevalence, “widespread food insecurity would lead to a rise in TB incidence in Zimbabwe, as such performed an ecological analysis of the TB incidence during crisis year (2008–2009)”. | 144 | 11,784 | 8838 | Ecological study | Research staff | Incidence of TB increased during crises or the dry season when food insecurity was highest. |

| Chileshe et al. (2010) [44] | Location: Community-level hospitals in rural settings in Zambia Population: Adults | “Highlight barriers that poor rural Zambians co-infected with tuberculosis (TB) and HIV and their households face in accessing ART Account for patient outcomes by the end of TB treatment and beyond”. | 10 | 9 | 7 | Ethnographic case study | Research staff, nurses, counselors | Economic barriers included: “being pushed into deeper poverty by managing TB, rural location, absence of any external assistance, and mustering time and extended funds for transport and ‘special food’ during and beyond the end of TB. In the case of death, funeral costs were astronomical” [43]. Social barriers included: “translocation, broken marriages, a subordinate household position, gender relations, denial, TB/HIV stigma and the difficulty of disclosure”. Health facility barriers involved “understaffing, many steps, lengthy procedures, and inefficiencies (lost blood samples, electricity cuts)”. |

| Chintu et al. (1995) [45] | Location: Hospitals in urban settings in Zambia Population: Hospitalized children | “Assess the impact of HIV-1 on common childhood diseases Determine the pattern of HIV-1 seroprevalence and mortality”. | 9 | 42 | 42 | Cross-sectional Study | Research staff | Prevalence of common childhood diseases and death caused by HIV status among children with any of the recorded childhood diseases. |

| Gebremichael et al. (2018) [46] | Location: Community-level, primary health centers, and hospitals in rural settings in Ethiopia Population: Adults | “Determine food insecurity and nutritional status and contextual determinants of malnutrition among people living with HIV/AIDS”. | 2 | 512 | 63 | Cross-sectional study | Community health workers | The findings revealed a high prevalence of malnutrition and household food insecurity among people living with HIV/AIDS on antiretroviral therapy. |

| Hanifa et al. (2018) [47] | Location: Primary health centers in the Gauteng Province of South Africa Population: Adults | Identify the causes of symptoms suggestive of TB among people living with HIV. | 3 | 103 | 14 | Cohort study | Research staff, physicians | Post-TB chronic lung disease and food insecurity were the main diagnoses for symptoms suggestive of TB in our population of HIV clinic attendees, and diagnoses were assigned for more than 90% of participants. |

| Kelly et al. (2002) [48] | Location: Rural communities in Zambia Population: Adults | To examine the relationship between morbidity, nutritional impairment, and CD4 count in patients with HIV infection. | 2 | 186 | 11 | Cross-sectional study | Research staff | The findings suggest that “effective treatment of opportunistic infection is likely to be important in preventing or reversing nutritional failure, even when food availability is limited”. |

| LaCourse et al. (2014) [49] | Location: Hospitals in peri-urban settings of Malawi Population: Children | Determine pulmonary tuberculosis prevalence among the hospitalized severely malnourished. | 2 | 300 | 52 | A prospective observational study | Hospital staff and patient guardians | Only 2 of 300 screened patients had a positive cultured confirmed positive pulmonary TB diagnosis. |

| Madebo et al. (1997) [50] | Location: Hospital in an urban setting in Ethiopia Population: Adults | Examine the influence of HIV infection and malnutrition on the radiological and clinical features of pulmonary TB. | 6 | 239 | 48 | Cross-sectional study | Research staff | “HIV-positive TB patients had significantly more oral candidiasis, diarrhea, generalized lymphadenopathy, skin disorders, neuropsychiatric illness, hilar lymphadenopathy, but less cavitation and upper lung lobe involvement. The size of the Mantoux was associated with HIV infection and malnutrition. Malnutrition and HIV infection both contribute to the atypical presentation of pulmonary tuberculosis. The risk of such atypical presentation is particularly high among the severely malnourished HIV-infected patients”. |

| Meressa et al. (2015) [51] | Location: Community-level hospitals in an urban setting in Ethiopia Population: Adults | “Determine the patient-related (or clinical) and programmatic factors associated with successful multidrug-resistant TB treatment outcomes in a highly resource-constrained setting”. “All patients received a monthly food basket. After assessment of the patient’s living conditions, those found to be vulnerable due to extreme poverty were provided economic assistance for transport, additional food, and house rent if needed throughout therapy”. | 60 | 612 | 133 | Cohort study | Existing nurses, clinical staff of the health facilities, and family treatment supporters | “Though nearly half of the cohort had severe malnutrition (BMI < 16), overall, 64.7% were cured, and 13.9% completed treatment for a combined treatment success of 78.6%”. “Amongst co-infected participants, 69.9% had treatment success. In total, 5.9% of patients were lost to follow-up, 1.6% failed treatment and 13.9% died. The presence of nutritional, social, and economic support during study duration contributed to treatment success”. |

| Mupere et al. (2012) (Low Nutrient) [52] | Location: Hospitals in an urban setting in Uganda Population: Adults | This cross-sectional study “was conducted to establish the relationship between nutrient intake and body wasting and between nutrient intake and severity of tuberculosis disease at the time of tuberculosis diagnosis”. | 7 | 131 | 31 | Cross-sectional study | Research staff, health facility staff, nurses, nutritionists | The study found that “the average 24-h nutrient intake varied by the severity of tuberculosis disease, but not by tuberculosis disease or HIV status nor by nutritional status”. The findings also suggest that “in the face of tuberculosis disease, nutrient intake is reduced among patients with more severe disease regardless of HIV infection. In the absence of tuberculosis, nutrient intake was affected by gender, and not HIV infection”. |

| Mupere et al. (2012) (Lean Tissue) [53] | Location: Community clinics in the Kampala District of Uganda Population: Adults | “The study was conducted to assess the impact of wasting on survival in tuberculosis and HIV patients using precise height-normalized lean tissue mass index (LMI) estimated by bioelectrical impedance analysis and BMI”. | 204 | 747 | At least 99 | Retrospective cohort study | Research staff | “Both low BMI and low LMI at tuberculosis diagnosis were associated with poor survival in univariate and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analyses”. “The unadjusted hazard ratio (HR) for death in a univariate model among patients with low BMI at diagnosis compared to patients who had normal BMI was 1.80 (95% CI: 1.23, 2.64). Similarly, the unadjusted HR for death among patients with low LMI compared to patients who had normal LMI was 2.34 (95% CI, 1.14, 4.80). Other univariate factors that were significantly associated with increased relative hazards of death included male gender, older age group >30 years, HIV seropositive status, and history of weight loss”. “The HR for death among patients with low BMI at presentation was 1.83 (95% CI, 1.24, 2.71) after adjusting for age, HIV, prior smoking status, the extent of disease on chest x-ray and history of weight loss”. “Men with low BMI at presentation had a greater risk of death compared with men who had normal BMI (HR = 1.70; 95% CI: 1.03, 2.81). Among women, those presenting with a low BMI compared with a normal BMI had a comparable risk of death (HR = 1.83; 95% CI: 0.96, 3.50)”. “Other factors that were associated with the risk of death in this model included older male gender, HIV seropositive status, and history of weight loss”. |

| Rudolph et al. (2013) [54] | Location: Community-level primary health centers in the urban setting of South Africa Population: Adults and children | “The aims of this 3-month pilot study with crèche children and adult TB patients in Alexandra, South Africa, were to generate baseline data on nutritional status, assess the impact of a fortified supplementary food (e’Pap) on nutritional status, and to evaluate the sensitivity and validity of non-invasive indicators of nutritional status”. | 3 | 153 | 58 | Pre–post pilot study | Research and health facility staff, community health workers | “Adult females were younger (mean age 34 years, STD 10 years) than males (mean age 40 years, STD 9 years). The mean age for female children was 4.6 years (STD 0.8 years) and for male children 4.7 years (STD 0.9 years). The median household size was 4 (Q1–Q3 3–4)”. “Unemployment was high among recruited adult participants-69% among males and 59% among females. 8 participants withdrew from the study reporting side effects like rashes, mouth sores, and vomiting. It was not possible to link the side effects to any particular cause, including consumption of the supplement”. |

| Sattler et al. (2018) [55] | Location: Hospitals in Kenya and South Africa Population: Adults | This study “hypothesized that greater malnutrition and/or inflammation when initiating treatment is associated with an increased risk for death”. | 12 | 51 | 51 | Retrospective case–cohort study | Research staff | “For the cohort of 51 participants, the 33 who survived were not different from the 18 who died. 14% of participants had BMI < 16.5 kg/m2 and 33% had BMI 16.5–18.5 kg/m2. The causes of death and week of death (in parentheses) in the ensuing year after randomization were disseminated: tuberculosis (2, 4), gastroenteritis (3, 5, 11), pulmonary tuberculosis (4, 10), acute renal failure (5), bacterial pneumonia (8, 34), cryptococcal meningitis (9), bacterial meningitis (13), bacterial sepsis (14), peritonitis (11), intracranial hypertension (16), gunshot wounds (24), tuberculous meningitis (40), and no information (23). Death could not be related to treatment assignment (early versus deferred ART). For measures of nutrition, hazard ratios for average BMI, low BMI, serum hemoglobin, serum albumin, and leptin were not significant risk factors for death, although there was a trend for increased risk of death with advancing age”. “Increased risk of death was significantly associated with CRP, but the only pro-inflammatory cytokine associated with a significant risk of death was IFNγ. MCP-3 was associated with risk of death, but MCP-1 was not”. “Global measures of the innate and adaptive immune responses were both strongly associated with risk of death”. |

| Schact et al. (2019) [56] | Location: Primary health centers in rural settings in Mozambique Population: Adults | “The purpose of this study was to elicit Mozambican patients with drug-sensitive TB (DS-TB), TB/HIV and Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) understanding and assessment of the quality of care for DS-TB, HIV/TB and MDR-TB services in Mozambique, along with challenges to effectively preventing, diagnosing, and treating TB”. | 1 | 51 | 19 | Qualitative study | Research staff | Themes from focus groups were classified under “(1) TB knowledge; (2) barriers to accessing services (including treatment); (3) barriers to treatment adherence, and (4) Suggestions for improvement for TB”. “Respondents identified numerous challenges including delays in diagnosis, stigma related with diagnosis and treatment, long waits at health facilities, the absence of nutritional support for patients with TB, the absence of a comprehensive psychosocial support program, and the lack of overall knowledge about TB or multidrug-resistant TB in the community”. |

| Wang et al. (2020) [57] | Location: Primary health centers in urban settings of Botswana Population: Adults | “To determine the association between food insecurity and HIV infection with depression and anxiety among new tuberculosis (TB) patients”. | 12 | 180 | 99 | Cross-sectional study | Research staff | “Among those who were HIV co-infected, the median duration since HIV diagnosis was 43 months, and 31(31.3%) had never taken ART, of whom 90% were newly diagnosed with HIV at or within one month of study enrolment”. “Higher prevalence of depression and anxiety in moderate to severe food insecure HIV-TB co-infected participants. Among HIV-co-infected participants, the estimates were similar in the bivariate analysis for depression (crude PR = 2.41; 95% CI 1.28, 4.55) and anxiety (crude PR = 1.54; 95% CI 1.04, 2.27). Accounting for ART status and CD4 count closest to the time of TB diagnosis, food insecurity continued to be associated with increased symptoms of depression (adjusted PR = 2.33; 95% CI 1.24, 4.38) and anxiety (adjusted PR = 1.53; 95% CI 1.03, 2.26) in the multivariable model”. |

| Author (Year) | Food Insecurity-Related Reports (HFIAS, Nutritional Metrics, or Narrative) | HIV-Related Health Outcomes | TB-Related Health Outcomes | Medication/Treatment Adherence or Behavior | Economic Drivers Influencing Food Insecurity | Was Intervention Successful (Y/N/NA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bakari et al. (2013) [41] | HFIAS average score 6 (range: 1–14) | “There was one reported death: a patient with a baseline BMI 21 kg/m2 and CD4 120 cells/μL who had gained 4 kg at 4 months, but remained sputum-positive, died at 5 months due to an undiagnosed febrile illness”. | NR | Twenty women (47%) were on ART but adherence was not reported. | NR | NA |

| Benzekri et al. (2019) [14] | Used HFIAS and indicators of nutritional status included weight, BMI, and percent malnourished. “The median weight increased from 50 kg at enrollment to 55 kg at month 6 and the median BMI increased from 17.3 kg/m2 to 19.3 kg/m2. At enrollment, 58% of subjects were malnourished versus 35% at month 6”. | NR | NR | “Overall, 7-day adherence, 4-week adherence, and medication possession exceeded 95% for both ART and TB treatment. Adherence did not differ between those who received ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF) and those who received food baskets”. | NR | Y |

| Bongongoet al. (2020) [42] | Had sufficient food daily for the past 12 months. “More participants (n = 124; 68.8%) were able to have at least one meal per day for the past 12 months. In all, 57 participants (45.9%) amongst those who had food were cured of TB”. | “More HIV negative participants (n = 33; 67.4%) were cured; more deaths (n = 22; 26.5%) and defaults (n = 26; 31.3%) were noted amongst HIV-positive patients”. “Association between TB patients on treatment who were cured, died or defaulted, when compared with their HIV status, was indicated by p = 0.001, 0.02 and 0.03 respectively”. | “57 participants (45.9%) amongst those who had food were cured. Whilst comparing the TB treatment outcomes and food security, an association of statistical significance in the group of relapses was noted, with p = 0.029”. “The effect of exposure to cigarette smoke in respondents’ families (passive or active) was evident. Of the 180 respondents with TB, 75 (67.6%) of the respondents who were not exposed to cigarette smoke were cured (p = 0.0001), whilst 45 (65.2%) of the respondents who were exposed to cigarette smoke died”. | “More deaths (n = 22; 26.5%) and defaults (n = 26; 31.3%) were noted amongst HIV-positive patients. Association between TB patients on treatment who were cured, died, or defaulted, when compared with their HIV status, as indicated by p = 0.001, 0.02 and 0.03 respectively”. | NR | NA |

| Burke et al. (2014) [43] | “Nutritional deficiencies reported include: The prevalence of kwashiorkor most significantly increased between 2001 (130 cases) and 2008 (239 cases) (p < 0.01). The prevalence of pellagra also rose between 2001 (31 cases) and 2004 (118 cases) (p < 0.01) and remained at this elevated level thereafter. Diarrhea, both with and without dehydration, increased over time (p < 0.01)”. | “Antenatal clinic HIV seroprevalence at HH decreased between 2001 (23%) to 2011 (11%) (p < 0.001). 75% of TB incidence in HIV population”. | “At the Howard Hospital (HH) in northern Zimbabwe, TB incidence increased 35% in 2008 from baseline rates in 2003–2007 (p < 0.01) and remained at that level in 2009. Murambinda Hospital (MH) in Eastern Zimbabwe also demonstrated a 29% rise in TB incidence from 2007 to 2008 (p < 0.01) and remained at that level in 2009. Data collected post-crisis at HH showed a decrease of 33% in TB incidence between 2009 to 2010 (p < 0.001) and 2010/2011 TB incidence remained below that of the crisis years of 2008/2009 (p < 0.01)”. | NR | Economic collapse and crisis, declining GDP per capita, a high prevalence of HIV. | NA |

| Chileshe et al. (2010) [44] | Narrated description: “Poverty was not regarded as a new phenomenon but embedded in seasonal patterns with food insecurity worse from October through to March. Illness and death were pinpointed as one of the main causes of current food shortages [43]”. Results: “The food insecurity of all six households had deepened by a period managing TB owing to loss of livelihood, assets, and income, a dip in productivity, mounting debt, and the cost of transport and requirements for ‘‘special food’’. None of the households received food aid or any other form of material assistance from the government, churches, or NGOs. All the seven co-infected participants spoke about their hunger and the need to take the medication with food. It was striking how the household diet had changed because of TB more fish, eggs, meat, soft drinks, and fruit were purchased; a sharp contrast to the normal household diet of vegetables and maize meal. For those co-infected and on ART, needing to eat to get well and take treatment was emerging as a more long-term problem”. | Out of the seven co-infected patients, two died before completing TB treatment. | “By the end of TB treatment, outcomes were mixed; two co-infected patients had died, three had started ART and two had yet to start ART”. | “Despite the free provision of both TB treatment and ART through government health services, co-infected patients faced economic, social, and health service facility barriers to accessing ART. In the study, two individuals reported being on ART but one stopped in 2008”. “Several of the participants reported not being able to access and adhere to treatment due to difficulty in being able to make it to the ART clinic due to family disapproval and transportation/economic barriers”. | “The food insecurity of all six households had deepened by a period managing TB owing to loss of livelihood, assets, and income, a dip in productivity, mounting debt, and the cost of transport and requirements for ‘special food’. Six of the seven co-infected participants had relocated whilst sick, five moving from town and having to leave their livelihoods behind. All TB patients were unable to contribute to the household living during their search for a diagnosis (which took between 220 months) and for at least four months into TB treatment; primary caregivers often found it hard to make a living just before and after TB diagnosis when patients were often extremely sick and required constant care or were admitted into the hospital. Five of the six households said that TB illness had disrupted their farming activities and made them less productive, with three households recording a drop in the maize they harvested and two households recording no harvest in 2006–2007”. | NA |

| Chintu et al. (1995) [45] | Use of nutritional metrics. Protein–energy malnutrition was reported as marasmus, kwashiorkor, and marasmic-kwashiorkor. | “94 children (40.5%) with malnutrition had HIV, 42 children (68.9%) with TB had HIV. 34/94 (36.2%) of children with malnutrition died from HIV; 7/42 (16.7%) of children with TB. The overall mortality among HIV-seropositive children (19 percent) was significantly higher than those who were HIV-seronegative (9 percent) (p < 0.001; overall odds ratio = 2.13; 95 percent CI = 1.49, 3.04)”. | 61 children with TB died. | NR | NR | NA |

| Gebremichael et al. (2018) [46] | HFIAS score 27 | HIV-induced immune impairment, increased risk of opportunistic infections, worsening of nutrition status. | Appetite loss, weight loss, wasting. | NR | “This study revealed that unemployed PWH were more likely to be undernourished compared with employed counterparts. The higher risk of developing malnutrition in unemployed subjects found in this study is supported by findings of other studies where unemployment promotes poverty, which in turn limits the ability of an individual to expend money for food consumption due to low income”. | NA |

| Hanifa et al. (2018) [47] | “HFIAS score: 50% (53 individuals) had severe food insecurity; On ART = 23 (46.0%); Not on ART = 30 (56.6%) Total average = 53 (51.5) HFIAS score: moderate food insecurity: On ART = 11 (22.0%); Not on ART = 8 (15.1%) Total average = 19 (18.5%) Weight loss due to severe food insecurity: n = 20 (19%)”. | “50/103 were pre-antiretroviral therapy (ART) and 53/103 were on ART; Seventy-two (70%) had 75% measured weight loss and 50 (49%) had cough. The most common final diagnoses were weight loss due to severe food insecurity (n = 20, 19%), TB (n = 14, 14%: confirmed n = 7; clinical n = 7), other respiratory tract infection (n = 14, 14%) and post-TB lung disease (n = 9, 9%)”. | Post-TB lung disease (n = 9, 9%). | NR | NR | NA |

| Kelly et al. (2002) [48] | “Height and BMI were low by comparison with norms in industrialized countries (Lentner, 1984), suggesting lifelong undernutrition in the population as a whole. Mean height was 1.58 m in women and 1.69 m in men (p < 0.0001). Mean BMI was 22.0 kg/m2 in women and 19.9 in men (p < 0.0001). MUAC also differed: mean MUAC was 27.3 cm in women and 26.3 in men (p = 0.04). BMI and MUAC were reduced in HIV seropositive adults with OIs”. | “65 participants were HIV positive; HIV seroprevalence was comparable to previous estimates of 22–35% for Lusaka. 33 (51%) of 65 HIV seropositive adults reported symptoms compared to 39 (32%) of 121 HIV seronegative adults (OR 2.2, 95%CI 1.1–4.2; p = 0.02) or 21 (28%) of 75 who were not tested (OR 2.7, CI 1.2–5.7; p = 0.01)”. | “The most frequently diagnosed clinical conditions in HIV-infected individuals were TB (n = 11). CD4 counts of less than 200 cells/L were found in 6/11 individuals with TB. Fourteen cases of TB were discovered including two who did not have HIV tests, five of which had previously been diagnosed”. | NR | NR | NA |

| LaCourse et al. (2014) [49] | “Enrollees were required to meet WHO severe acute malnutrition criteria for children aged 6–60 months with weight-for-height z-score ≤−3 standard deviations below the median, mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) ≤115 mm, or bilateral pedal edema”. | NR | Lethargy/fatigue | NR | NR | NA |

| Madebo et al. (1997) [50] | “187 (77.9%) of the patients had a BMI < 18.5. Based on BMI assessment, 44 (18.2%)) were mildly, 39 (16.1%) moderately and 104 (43%) were severely malnourished. Based on MUAC assessment 161/167 (96.4) of men (MUAC ≤ 24 cm) and 71/75 (94.7%) of women (MUAC ≤ 23 cm) were malnourished. The mean BMI was 16.2 (SD 2.6) and 16.6 (SD 2.4) for HIV-positive and -negative patients, respectively”. | NR | NR | NR | NR | NA |

| Meressa et al. (2015) [51] | “Provision of a monthly food basket and in some extreme cases of poverty, provision of economic assistance for transport, additional food, and house rent if needed throughout Therapy. The median body mass index (BMI) was 16.6 (IQR 14.8–19.1). Treatment failure or death among MDR-TB patients was higher in patients who had severe malnutrition (BMI < 16 kg/m2) (15.1% vs. 6.8%, p = 0.003)”. | “Treatment success rates were higher for HIV-uninfected compared with HIV-infected individuals (81.0% vs. 69.9%, p = 0.008). Treatment failure or death was higher in HIV-infected patients”. | NR | “Of the 133 HIV-co-infected patients, 120 had begun ART before enrolment. Eleven patients were started on ART after initiation of MDR TB treatment and two declined ART. ART regimen data were available for 115 patients. The median duration of injectable use for the TB meds was 9.6 months (IQR 8.1–11.0 months)”. | “Extreme poverty was addressed by initiating monthly home visits and monthly patient visits to the treatment initiation site’s outpatient department, identification of a patient supporter to assist with DOT, psychosocial support, monthly food baskets, and social support for the most destitute patients. All patients in the program received food parcels to address the high rates of undernutrition. There is profound malnutrition and the gastrointestinal toxicities noted during MDR TB treatment in most cohorts from resource-constrained settings”. | Y |

| Mupere et al. (2012) [Low nutrient] [52] | Use of nutritional metrics such as BMI and weight to estimate food insecurity-related malnutrition, body wasting of participants using body mass index (BMI), and height-normalized indices (adjusted for height) for body composition of lean mass index (LMI) and fat mass index (FMI) [50]. Bioelectrical impedance analyzer (BIA) measures. Twenty-four-hour nutrient intake. | “There were no differences in average 24-h nutrient intake by Tuberculosis disease and HIV status”. | “There were no differences in average 24-h nutrient intake by Tuberculosis disease and HIV status. Loss of appetite, vomiting, fainting, loss of body mass, wasting, death”. | NR | NR | NA |

| Mupere et al. (2012) [Lean tissue] [53] | “Nutritional status was assessed using baseline height and weight anthropometric measurements and BIA before initiation of tuberculosis therapy. Lean tissue mass was calculated from BIA measurements using equations that were previously cross-validated in a sample of patients with and without HIV infection and have been applied elsewhere in African studies. Fat mass was calculated as body weight minus fat-free mass. Baseline wasting was defined using BMI and height-normalized indices (adjusted for height) for lean tissue mass and fat mass as measured by BIA. BMI can be partitioned into height-normalized indices of lean tissue mass index (LMI) and fat mass index (FMI), i.e., BMI = LMI + FMI as previously reported using BMI cutoff for malnutrition < 18.5 kg/m2. The cutoffs for low LMI and FMI corresponding to a BMI < 18.5 kg/m were as follows: LMI < 16.7 (kg/m2) for men and <14.6 (kg/m2) for women with corresponding FMI < 1.8 (kg/m2) for men and <3.9 (kg/m2) for women. LMI and FMI have the advantage of compensating for differences in height and age”. | Higher hazard of death among HIV seropositive participants. | “Loss of appetite, vomiting, fainting, loss of body mass, wasting, death”. | NR | NR | NA |

| Rudolph et al. (2013) [54] | “Nearly all adults (97% of females and 96% of males) reported being food insecure. Food insecurity was also relatively high (57%) among children as reported by parents/guardians. Reported levels of food security did not change throughout the study [52]”. “Mean dietary diversity scores for adults were below the minimum target of 7 out of 12 (adult males 6.1; adult females 5.0; child males 7.3; child females 7.5). Diets-particularly among adults-reflected a strong reliance on starchy staples (refined maize porridge and bread), with lower consumption of protein, fruit, and vegetables”. “The mean baseline BMI among adult males was low (19.2), while in adult females it was normal (23.3). All groups exhibited an increase in BMI, while waist to hip ratios remained stable. Child baseline median body weight was 18.1 kg for girls and 17.2 kg for boys, compared to WHO international growth standards of 18.2 kg for girls and 18.3 kg for boys”. | “67% of the adult TB patients (76% of females; 54% of males) self-reported as being HIV positive. There were no reports of HIV-positive serology in the child cohort. HIV negative adults showed greater improvement (mean change of 0.013, 95% CI −0.020–0.006) over three months than HIV positive adults (mean change of 0.007, 95% CI −0.021–0.082)”. | NR | NR | “The high rates of unemployment and self-reported HIV positive status among the adult cohort are above the national averages, but these findings are not surprising in the resource-poor setting of Alexandra and context of widespread co-infection with HIV and TB”. | Y |

| Sattler et al. (2018) [55] | “Of note, 7 (14%) participants had BMI < 16.5 kg/m2 and 17 (33%) had BMI 16.5–18.5 kg/m2”. | NR | “For the cohort of 51 participants, the 33 who survived were not different from the 18 who died”. | NR | NR | NA |

| Schact et al. (2019) [56] | A narrated description of food insecurity was used. The effect of treatment for HIV/AIDS is being hungry and this is a problem if no food at home. | NR | NR | Social-level barriers: stigma. Individual-level barriers: lack of prioritization of treatment, participants rapidly felt better and did not feel like completing the therapy, side effects of ART use such as pain in legs and articulations; itching; weakness and vertigo; swollen feet were mentioned, particularly in patients with TB/HIV co-infection [54]. Health facility-level barriers: delayed access to services, hygienic conditions were also mentioned as another negative aspect of the services, such as water cups used for patients to take their medications were not cleaned from one patient to the next. | NR | NA |

| Wang et al. (2020) [57] | Used the HFIAS. “Over half of all participants reported being food secure, and 15 (8.4%), 17 (9.5%) and 52 (29.0%) reported experiencing mild insecurity, moderate insecurity, and severe insecurity, respectively”. | NR | NR | “Among those who were HIV co-infected, the median duration since HIV diagnosis was 43 months, and 31(31.3%) had never taken ART, of whom 90% were newly diagnosed with HIV at or within one month of study enrolment ”. | NR | NA |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ojo, T.; Ruan, C.; Hameed, T.; Malburg, C.; Thunga, S.; Smith, J.; Vieira, D.; Snyder, A.; Tampubolon, S.J.; Gyamfi, J.; et al. HIV, Tuberculosis, and Food Insecurity in Africa—A Syndemics-Based Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031101

Ojo T, Ruan C, Hameed T, Malburg C, Thunga S, Smith J, Vieira D, Snyder A, Tampubolon SJ, Gyamfi J, et al. HIV, Tuberculosis, and Food Insecurity in Africa—A Syndemics-Based Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(3):1101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031101

Chicago/Turabian StyleOjo, Temitope, Christina Ruan, Tania Hameed, Carly Malburg, Sukruthi Thunga, Jaimie Smith, Dorice Vieira, Anya Snyder, Siphra Jane Tampubolon, Joyce Gyamfi, and et al. 2022. "HIV, Tuberculosis, and Food Insecurity in Africa—A Syndemics-Based Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 3: 1101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031101

APA StyleOjo, T., Ruan, C., Hameed, T., Malburg, C., Thunga, S., Smith, J., Vieira, D., Snyder, A., Tampubolon, S. J., Gyamfi, J., Ryan, N., Lim, S., Santacatterina, M., & Peprah, E. (2022). HIV, Tuberculosis, and Food Insecurity in Africa—A Syndemics-Based Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031101