Integrating Key Nursing Measures into a Comprehensive Healthcare Performance Management System: A Tuscan Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Section/Topic | Item No | Checklist Item | Reported on Page No |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain 1: Research Team and Reflexivity | |||

| Personal characteristics | |||

| Interviewer/facilitator | 1 | Which author/s conducted the interview or focus group?Interviewer/facilitator | 4 |

| Credentials | 2 | What were the researcher’s credentials? E.g., Ph.D., MD | 4 |

| Occupation | 3 | What was their occupation at the time of the study? | 1 |

| Gender | 4 | Was the researcher male or female? | Not reported |

| Experience and training | 5 | What experience or training did the researcher have? Relationship with participants | 4 |

| Relationship with participants | |||

| Relationship established | 6 | Was a relationship established prior to study commencement? | 4 |

| Participant knowledge of the interviewer | 7 | What did the participants know about the researcher? E.g., personal goals, reasons for doing the research | 4 |

| Interviewer characteristics | 8 | What characteristics were reported about the interviewer/facilitator? E.g., bias, assumptions, reasons, and interests in the research topic | 4 |

| Domain 2: Study Design | |||

| Theoretical framework | |||

| Methodological orientation and theory | 9 | What methodological orientation was stated to underpin the study? E.g., grounded theory, discourse analysis, ethnography, phenomenology, content analysis | 3 |

| Participant selection | |||

| Sampling | 10 | How were participants selected? E.g., purposive, convenience, consecutive, snowball | 4 |

| Method of approach | 11 | How were participants approached? E.g., face-to-face, telephone, mail, email | 4 |

| Sample size | 12 | How many participants were in the study? | 4 |

| Non-participation | 13 | How many people refused to participate or dropped out? Reasons? | 4 |

| Setting of data collection | 14 | Where were the data collected? E.g., home, clinic, workplace | 4 |

| Presence of non-participants | 15 | Was anyone else present besides the participants and researchers? | N/A |

| Description of sample | 16 | What are the important characteristics of the sample? E.g., demographic data, date | 4 |

| Data collection | |||

| Interview guide | 17 | Were questions, prompts, guides provided by the authors? Was it pilot tested? | N/A |

| Repeat interviews | 18 | Were repeat interviews carried out? If yes, how many? | N/A |

| Audio/visual recording | 19 | Did the research use audio or visual recording to collect the data? | 4 |

| Field notes | 20 | Were field notes made during and/or after the interview or focus group? | 4 |

| Duration | 21 | What was the duration of the interviews or focus group? | 4 |

| Data saturation | 22 | Was data saturation discussed? | N/A |

| Transcripts returned | 23 | Were transcripts returned to participants for comment and/or correction? | 4 |

| Domain 3: Analysis and Findings | |||

| Data analysis | |||

| Number of data coders | 24 | How many data coders coded the data? | 4 |

| Description of the coding tree | 25 | Did authors provide a description of the coding tree? | N/A |

| Derivation of themes | 26 | Were themes identified in advance or derived from the data? | 4 |

| Software | 27 | What software, if applicable, was used to manage the data? | N/A |

| Participant checking | 28 | Did participants provide feedback on the findings? | 4 |

| Reporting | |||

| Quotations presented | 29 | Were participant quotations presented to illustrate the themes/findings? Was each quotation identified? E.g., participant number | N/A |

| Data and findings consistent | 30 | Was there consistency between the data presented and the findings? | 4 |

| Clarity of major themes | 31 | Were major themes clearly presented in the findings? | 5/7 |

| Clarity of minor themes | 32 | Is there a description of diverse cases or discussion of minor themes? | 11/15 |

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. The National Database of Nursing Indicators (NDNQI®)

Appendix B.2. Collaborative Alliance for Nursing Outcomes (CaLNOC)

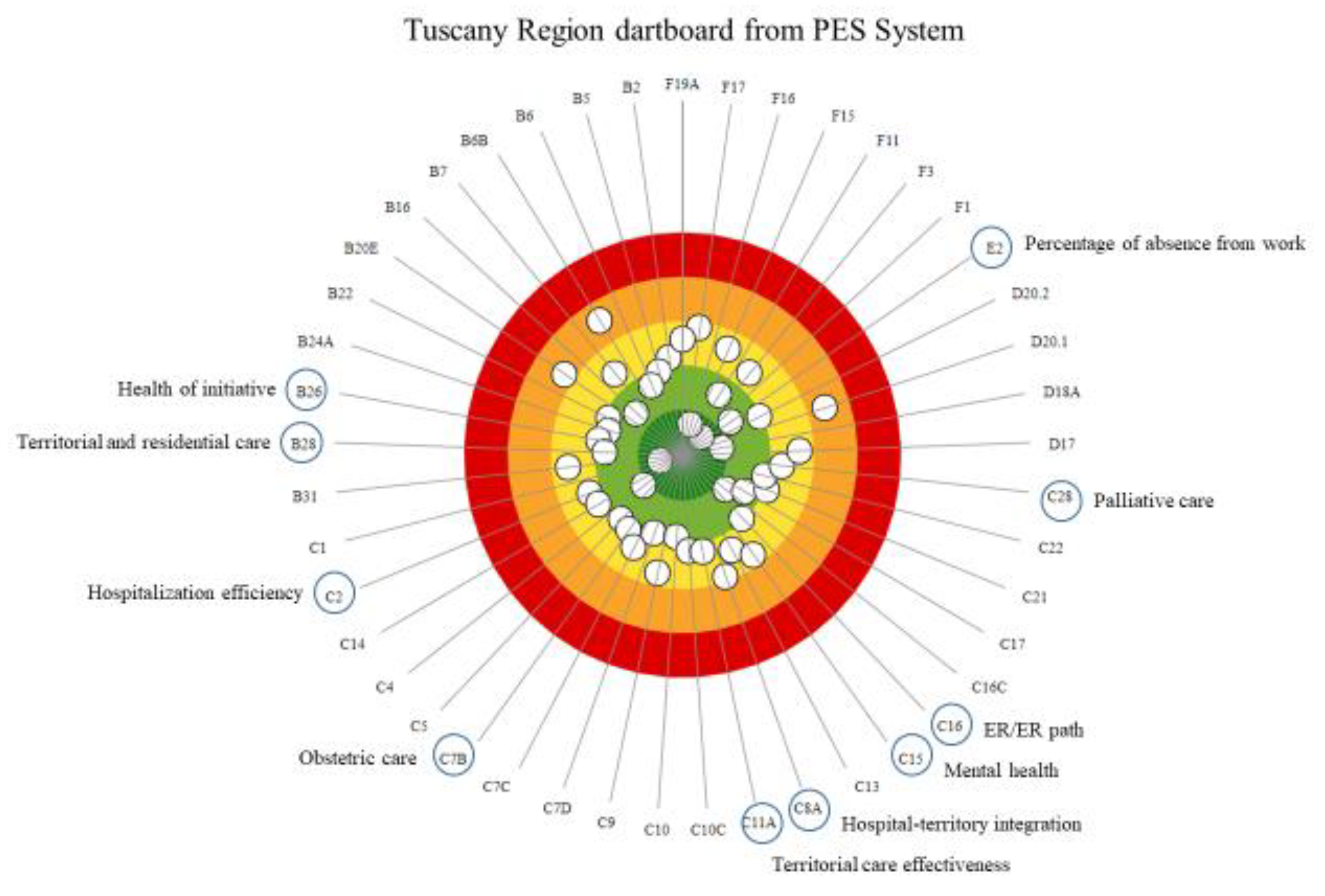

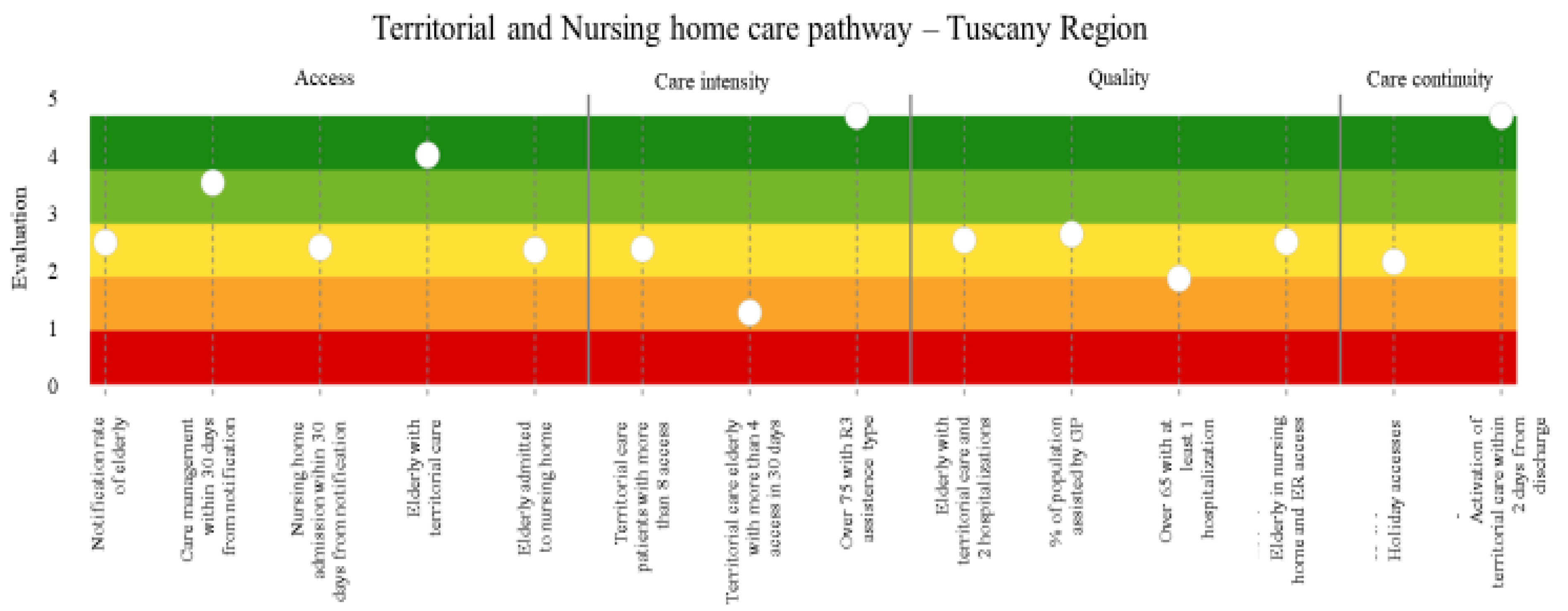

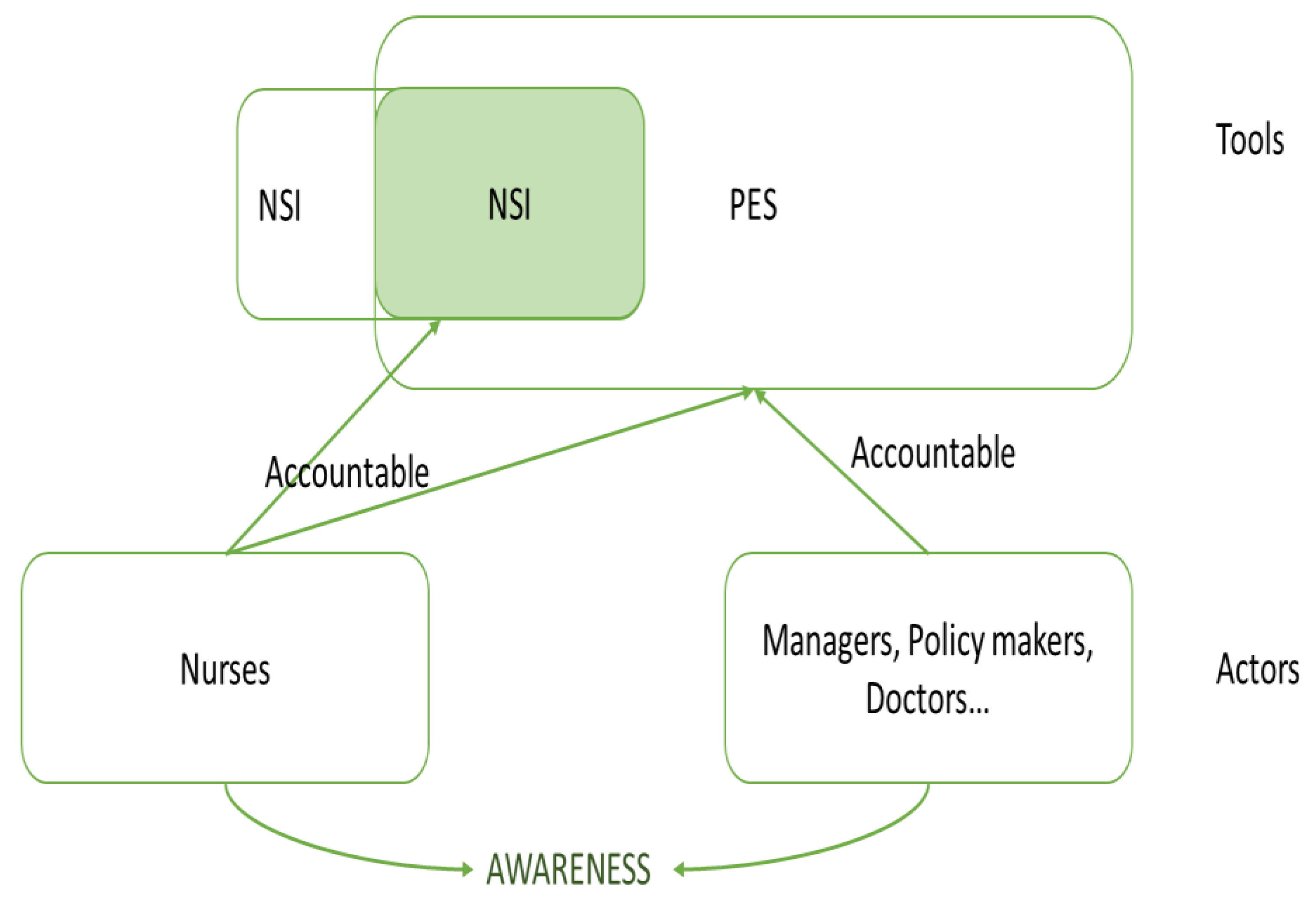

Appendix B.3. The Performance Evaluation System Experience (PES) and the Nursing Dimension

References

- Hood, C. A Public Management for All Seasons? Public Adm. 1991, 69, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapsley, I. Accounting and the New Public Management: Instruments of Substantive Efficiency or a Rationalising Modernity? Financ. Account. Manag. 1999, 15, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainieri, M.; Noto, G.; Ferrè, F.; Rosella, L. A Performance Management System in Healthcare for All Seasons? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veillard, J.; Champagne, F.; Klazinga, N.; Kazandjian, V.; Arah, O.A.; Guisset, A. A performance assessment framework for hospitals: The WHO regional office for Europe PATH project. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2005, 17, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arah, O.A.; Westert, G.P.; Hurst, J.; Klazinga, N.S. A conceptual framework for the OECD Health Care Quality Indicators Project. Int. J. Qual. Health Care. 2006, 18 (Suppl. 1), 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behn, R.D. Why measure performance? Different purposes require different measures. Public Adm. Rev. 2003, 63, 586–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizarondo, L.; Grimmer, K.; Kumar, S. Assisting allied health in performance evaluation: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fekri, O.; Klazinga, N. Health System Performance Assessment in the WHO European Region: Which Domains and Indicators Have Been Used by Member States for Its Measurement? In Health Evidence Network Synthesis Report; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bovens, M. Analysing and assessing accountability: A conceptual framework. Eur. Law J. 2007, 13, 447–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanicolas, I.; Smith, P. Health System Performance Comparison: An Agenda for Policy, Information and Research: An Agenda for Policy, Information and Research; McGraw-Hill Education: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Plsek, P.E.; Greenhalgh, T. The challenge of complexity in health care. Br. Med. J. 2001, 323, 625–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, B.W.; Alford, J. Wicked problems: Implications for public policy and management. Adm. Soc. 2015, 47, 711–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.J.; Evans, D.B. Health Systems Performance Assessment: Goals, Framework and Overview. Health System Performance Assessment: Debates, Methods and Empiricism; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kruk, M.E.; Freedman, L.P. Assessing health system performance in developing countries: A review of the literature. Health Policy 2008, 85, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pronovost, P.; Lilford, R. A Road Map for Improving the Performance of Performance Measures. Health Aff. 2011, 30, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuti, S.; Noto, G.; Vola, F.; Vainieri, M. Let’s play the patients music: A new generation of performance measurement systems in healthcare. Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 2252–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, P.; Jones, S.; Maben, J.; Murrells, T. State of the Art Metrics for Nursing: A Rapid Appraisal; Kings’ College London, University of London: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Heslop, L.; Lu, S.; Xu, X. Nursing-sensitive indicators: A concept analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, 70, 2469–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krau, S.D. Using nurse-sensitive outcomes to improve clinical practice. Crit. Care Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2001, 13, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planas-Campmany, C.; Icart-Isern, M.T. Nusing-sensitive indicadors: An opportunity for measuring the nurse contribution. Enferm. Clin. 2014, 24, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culler, S.D.; Hawley, J.N.; Naylor, V.; Rask, K.J. Is the availability of hospital IT applications associated with a hospital’s risk adjusted incidence rate for patient safety indicators: Results from 66 Georgia hospitals. J. Med. Syst. 2007, 31, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donabedian, A. Models for Organizing the Delivery of Personal Health Services and Criteria for Evaluating Them. Milbank Mem. Fund Q. 1972, 50, 103–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needleman, J.; Kurtzman, E.T.; Kizer, K.W. Performance measurement of nursing care: State of the science and the current consensus. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2007, 64 (Suppl. 2), 10–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocco, G.; Affonso, D.D.; Mayberry, L.J.; Stievano, A.; Alvaro, R.; Sabatino, L. The Evolution of Professional Nursing Culture in Italy: Metaphors and Paradoxes. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2014, 1, 2333393614549372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Health at a Glance: Europe 2020: State of Health in the EU Cycle; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- De Maeseneer, J.; Bourek, A.; McKee, M.; Brouwer, W. Task Shifting and Health System Design: Report of the Expert Panel on Effective Ways of Investing in Health (EXPH); Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Halcomb, E.; Williams, A.; Ashley, C.; McInnes, S.; Stephen, C.; Calma, K.; James, S. The support needs of Australian primary health care nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 1553–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rais, N.C.; Au, L.; Tan, M. COVID-19 Impact in Community Care—A Perspective on Older Persons with Dementia in Singapore. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministero della Salute. Patto per la Salute 2019–2020. Available online: alute.gov.it/portale/news/p3_2_1_1_1.jsp?lingua=italiano&menu=notizie&p=null&id=4001 (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- DPCM n. 73 del 17 Maggio 2020. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2021/05/25/21G00084/sg (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Nuti, S.; Seghieri, C.; Vainieri, M. Assessing the effectiveness of a performance evaluation system in the public health care sector: Some novel evidence from the Tuscany region experience. J. Manag. Gov. 2012, 17, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyegoke, A. The constructive research approach in project management research. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2011, 4, 573–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalvo, I. The National Database of Nursing Quality IndicatorsTM (NDNQI ®). OJIN Online J. Issues Nurs. 2007, 12, 112–214. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, N.E.; Rutledge, D.N.; Ashley, J. Outcomes of adoption: Measuring evidence uptake by individuals and organizations. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2004, 1, S41–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, C.E.; Bolton, L.B.; Donaldson, N.; Brown, D.S.; Mukerji, A. Beyond nursing quality measurement: The nation’s first regional nursing virtual dashboard. In Advances in Patient Safety: New Directions and Alternative Approaches (Vol 1: Assessment); Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Garrard, L.; Boyle, D.K.; Simon, M.; Dunton, N.; Gajewski, B. Reliability and validity of the NDNQI® injury falls measure. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2016, 38, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.; Bergquist, S.; Gajewski, B.; Dunton, N. Reliability testing of the National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators pressure ulcer indicator. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2006, 21, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CALNOC. The CALNOC Registry. 2017. Available online: http://calnoc.org/ (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Cleary, P.D. Evolving concepts of patient-centered care and the assessment of patient care experiences: Optimism and opposition. J. Health Polit. Policy Law. 2016, 41, 675–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuti, S.; De Rosis, S.; Bonciani, M.; Murante, A.M. Rethinking healthcare performance evaluation systems towards the people-centredness approach: Their pathways, their experience, their evaluation. Healthc. Pap. 2017, 17, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzini, S.; Furlan, M. L’esercizio delle competenze manageriali e il clima interno. Il caso del Servizio Sanitario della Toscana. Psicol. Soc. 2012, 7, 429–446. [Google Scholar]

- Bevan, G.; Evans, A.; Nuti, S. Reputations count: Why benchmarking performance is improving health care across the world. Health Econ. Policy Law. 2018, 14, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chassin, M.; Hannan, E.L.; DeBuono, B.A. Benefits and Hazards of Reporting Medical Outcomes Publicly. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 334, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannion, R.; Davies, H.T.O. Reporting health care performance: Learning from the past, prospects for the future. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2002, 8, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibbard, J.H.; Stockard, J.; Tusler, M. Does publicizing hospital performance stimulate quality improvement efforts? Health Aff. 2003, 22, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, P.; Vainieri, M.; Bonini, A.; Nuti, S.; Calnan, M. What might the English NHS learn about quality from Tuscany? Moving from financial and bureaucratic incentives towards ‘social’ drivers. Soc. Public Policy Rev. 2012, 6, 30–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bevan, G. House of Commons Health Committee Inquiry into Commissioning. Available online: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200910/cmselect/cmhealth/268/268ii.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Tong, A.; Sainsubury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainieri, M.; Seghieri, C.; Barchielli, C. Influences over Italian nurses’ job satisfaction and willingness to recommend their workplace. Health Serv. Manag. Res. 2020, 34, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohmola, A.; Saarnio, R.; Mikkonen, K.; Kyngäs, H.; Elo, S. Competencies relevant for gerontological nursing: Focus-group interviews with professionals in the nursing of older people. Nord. J. Nurs. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D.; Lindgren, S.C. The global role of the doctor in healthcare. World Med. Health Policy 2010, 2, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbot, L.; Verrinder, G. Promoting Health: The Primary Health Care Approach; Elsevier: Chatswood, NSW, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sarti, T.D.; Lazarini, W.S.; Fontenelle, L.F.; Almeida, A.P.S.C. What is the role of Primary Health Care in the COVID-19 pandemic? SciELO Brasil 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. A Vision for Primary Health Care in the 21st Century: Towards Universal Health Coverage and the Sustainable Development Goals; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ting, I.W.K.; Tebourbi, I.; Lu, W.-M.; Kweh, Q.L. The effects of managerial ability on firm performance and the mediating role of capital structure: Evidence from Taiwan. Financ. Innov. 2021, 7, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, G.; Xiao, H.; Cao, M.; Lee, L.H. Optimal computing budget allocation for the vector evaluated genetic algorithm in multi-objective simulation optimization. Automatica 2021, 129, 109599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicators for Nursing Management | Level of Governance 1 | Overlapping International Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Evaluation | ||

| O | |

| O | |

| O | |

| O | |

| O | |

| O | |

| O | |

| O | |

| H | |

| O | NDNQI® |

| NH | NDNQI® |

| NH | NDNQI® |

| NH | |

| NH | NDNQI® CaLNOC |

| NH | NDNQI® CaLNOC |

| NH | |

| NH | |

| NH | |

| NH | |

| NH | |

| Patient Experience | ||

| H | |

| H | |

| H | |

| H | |

| H | |

| Employee Voice | ||

| O | |

| O | |

| H | |

| H | |

| H | |

| O | |

| H | |

| O | |

| Regional Strategies | ||

| O | |

| C | |

| C | |

| C | |

| C | |

| C | |

| C | |

| C | |

| C | |

| C | |

| C | |

| C | |

| H | |

| O | |

| C | |

| C | |

| C | |

| C | |

| C | |

| C | |

| C | |

| H | |

| H | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barchielli, C.; Rafferty, A.M.; Vainieri, M. Integrating Key Nursing Measures into a Comprehensive Healthcare Performance Management System: A Tuscan Experience. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1373. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031373

Barchielli C, Rafferty AM, Vainieri M. Integrating Key Nursing Measures into a Comprehensive Healthcare Performance Management System: A Tuscan Experience. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(3):1373. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031373

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarchielli, Chiara, Anne Marie Rafferty, and Milena Vainieri. 2022. "Integrating Key Nursing Measures into a Comprehensive Healthcare Performance Management System: A Tuscan Experience" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 3: 1373. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031373

APA StyleBarchielli, C., Rafferty, A. M., & Vainieri, M. (2022). Integrating Key Nursing Measures into a Comprehensive Healthcare Performance Management System: A Tuscan Experience. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1373. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031373