Is Anyone Else Feeling Completely Nonessential? Meaningful Work, Identification, Job Insecurity, and Online Organizational Behavior during a Lockdown in The Netherlands

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theory and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Conservation of Resources

2.2. Relationships between Work Left during Lockdown and Work Perceptions

2.3. Relationships between Work Perceptions and Online Organizational Behaviors during Lockdown

3. Materials and Methods

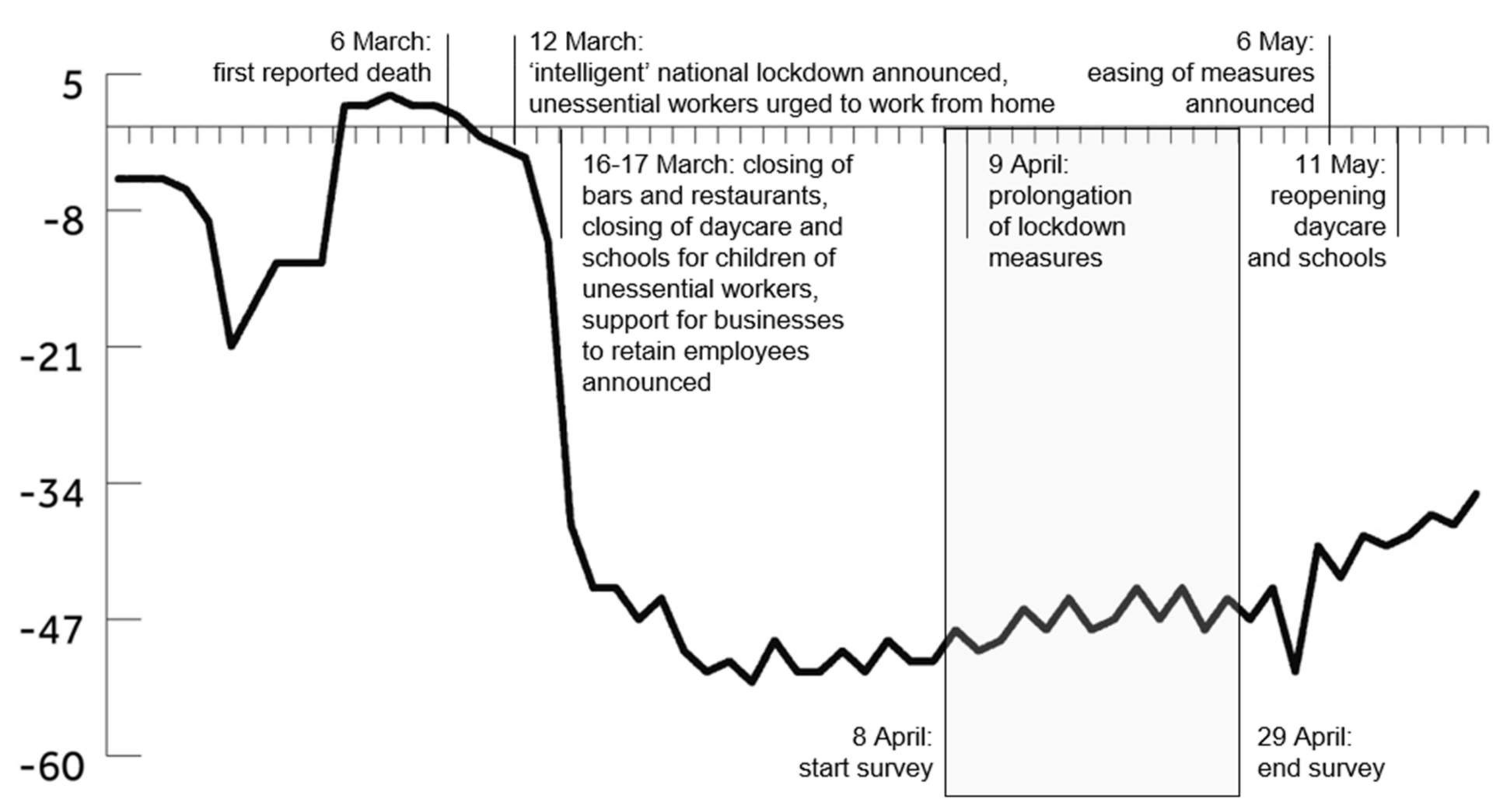

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Control Variables

- (1)

- Job background questions. Respondents were asked what type of job they had (full-time, n = 179; part-time, n = 107; side job combined with education, n = 81; paid traineeship, n = 7; paid internship, n = 34), how long they had been working for their current employer (less than six months, n = 63; 6–12 months, n = 61; 1–5 years, n = 152; 6–10 years, n = 34; 11–15 years, n = 25; 16–20 years, n = 12; or more than 20 years, n = 61), how many hours a week they worked before the lockdown (normal job hours; M = 29.83; SD = 12.57), and whether they had a supervisory function (n = 101) or not (n = 307).

- (2)

- Organizational background questions. Respondents were asked to estimate the size of the organization or organizational branch they worked for (1–5, n = 23; 6–10, n = 25; 11–99, n = 131; 100–200, n = 57; 201–1000, n = 70; more than 1000 people, n = 102) and their employer’s economic sector (see Table 1).

- (3)

- Personal background questions. Respondents also were asked for their gender at birth (n male = 160; n female = 248), age (M = 29.83; SD = 12.57), and highest completed education level (no education, n = 0; primary school, n = 0; high school, n = 54; lower professional education, n = 2; intermediate professional education, n = 59; higher professional education, n = 157; university, n = 136). Furthermore, respondents were asked whether they lived with others (a partner, parents, or in a communal living arrangement, n = 337) or alone (n = 71). We also asked whether their household included any children (n yes = 116); if so, whether these children required care during the day (n yes = 40); and if so, whether they had to provide childcare themselves during lockdown (n yes = 38). We referred to the latter measure as increased care responsibilities.

- (4)

- Days in lockdown. Days in lockdown were assessed as the days in April 2020 (8–29 April) when the respondent completed the survey (M = 11.17; SD = 4.85).

3.2.2. Work Percentage Left during Lockdown

3.2.3. (Increased) Telework Percentage

3.2.4. Work Perceptions

3.2.5. Online Organizational Behaviors

4. Results

4.1. Relationships between Work Remaining Active during Lockdown and Work Perceptions

4.2. Relationships between Work Perceptions and Online Organizational Behaviors during Lockdown

5. Discussion

5.1. Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Exploratory Factor Analysis of Online Organizational Behaviors

| Component | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How often do you … | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Help direct colleagues via email, chat, videoconferencing or social media when they have a work-related problem? | 0.82 | |||

| Make suggestions to direct colleagues via email, chat, videoconferencing or social media to make the performance of their job easier? | 0.93 | |||

| Support your direct colleagues via email, chat, videoconferencing or social media when they feel uncomfortable or have a bad day? | 0.54 | |||

| Respond positively to messages of direct colleagues on social media (for example, by “liking” them)? * | 0.76 | |||

| Speak positively about your organization via email, chat, videoconferencing or social media? | 0.71 | |||

| Make suggestions for improvements within your organization via email, chat, videoconferencing or social media?* | 0.42 | 0.32 | ||

| Defend your organization via email, chat, videoconferencing or social media? | 0.51 | |||

| Respond positively to messages of your organization on social media (for example, by “liking” them) | 0.76 | |||

| Deliberately not forward an email to someone at work, although you know this is important for him or her? | 0.46 | |||

| On purpose omit information in an email to someone at work, although you know this information is important to him or her? | 0.69 | |||

| Deliberately wait a long time when responding to an email that is directed to you personally from someone at work? | 0.78 | |||

| Completely ignore an email that is directed to you personally from someone at work? | 0.74 | |||

| Send an impolite email to someone at work? | 0.69 | |||

| Make fun of a colleague in an email? | 0.85 | |||

| Send an angry email to someone at work? | 0.71 | |||

| Use CAPS in an email to someone at work to “shout’” | 0.67 | |||

| Eigenvalue | 4.20 | 3.15 | 1.44 | 1.37 |

| Cumulative % of variance explained | 26.24 | 45.92 | 54.90 | 63.47 |

References

- Derks, P. Zinloze Nederlanders, Deze Is Voor Jullie. De Nieuws BV [Radio Broadcast]. NPO Radio1. Available online: https://www.nporadio1.nl/opinie-commentaar/22429-zinloze-nederlanders-deze-is-voor-jullie (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- Buddemeyer, R. I’m a Beauty Editor and Feel F*cking Useless Right Now. Is Anyone Else Feeling Completely Unessential? Available online: https://www.cosmopolitan.com/style-beauty/beauty/a32175767/social-distancing-beauty-editor-job-essay/ (accessed on 17 April 2020).

- Kramer, A.; Kramer, K.Z. The potential impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on occupational status, work from home, and occupational mobility. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 119, 103442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartel, C.A.; Wrzesniewski, A.; Wiesenfeld, B.M. Knowing where you stand: Physical isolation, perceived respect, and organizational identification among virtual employees. Organ. Sci. 2012, 23, 743–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Cuyper, N.; De Witte, H.; Vander Elst, T.; Handaja, Y. Objective threat of unemployment and situational uncertainty during a restructuring: Associations with perceived job insecurity and strain. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-J.; Demerouti, E.; Le Blanc, P.; Lu, C.-Q. Crafting a job in ‘tough times’: When being proactive is positively related to work attachment. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2018, 91, 569–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.; Hsu, D.Y.; Yim, F.H.; Zou, Y.; Chen, H. Wish-making during the COVID-19 pandemic enhances positive appraisals and job satisfaction. J. Vocat. Behav. 2021, 130, 103619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto-Rubio, A.; Giménez-Espert, M.; Prado-Gascó, V. Effect of emotional intelligence and psychosocial risks on burnout, job satisfaction, and nurses’ health during the covid-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prime, H.; Wade, M.; Browne, D.T. Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnevale, J.B.; Hatak, I. Employee adjustment and well-being in the era of COVID-19: Implications for human resource management. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Kumar, N.; Aggarwal, P.; Yeap, J.A.L. Working in lockdown: The relationship between COVID-19 induced work stressors, job performance, distress, and life satisfaction. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 6308–6323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P. Work from home—Work engagement amid COVID-19 lockdown and employee happiness. J. Public Aff. 2021, 21, e2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, A.A.; Sayre, G.M.; French, K.A. “A blessing and a curse”: Work loss during coronavirus lockdown on short-term health changes via threat and recovery. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2021, 26, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meseguer de Pedro, M.; Fernández-Valera, M.M.; García-Izquierdo, M.; Soler-Sánchez, M.I. Burnout, psychological capital and health during COVID-19 social isolation: A longitudinal analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Harrison, S.H.; Corley, K.G. Identification in organizations: An examination of four fundamental questions. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 325–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Riketta, M.; Van Dick, R. Foci of attachment in organizations: A meta-analytic comparison of the strength and correlates of workgroup versus organizational identification and commitment. J. Vocat. Behav. 2005, 67, 490–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carusone, N.; Pittman, R.; Shoss, M. Sometimes it’s personal: Differential outcomes of person vs. job at risk threats to job security. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhumika, B. Challenges for work–life balance during COVID-19 induced nationwide lockdown: Exploring gender difference in emotional exhaustion in the Indian setting. Gend. Manag. 2020, 35, 705–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent-Lamarche, A.; Boulet, M. Employee well-being in the COVID-19 pandemic: The moderating role of teleworking during the first lockdown in the province of Quebec, Canada. Work 2021, 70, 763–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, A.A.; Cropanzano, R. The conservation of resources model applied to work–family conflict and strain. J. Vocat. Behav. 1999, 54, 350–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Halbesleben, J.R.; Neveu, J.P.; Paustian-Underdahl, S.C.; Westman, M. Getting to the “COR” understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1334–1364. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 50, 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellevis, J. We Gaan Weer Vaker Naar Kantoor, Goed Ventileren Is Belangrijk. Available online: https://nos.nl/collectie/13839/artikel/2334731-we-gaan-weer-vaker-naar-kantoor-goed-ventileren-is-belangrijk (accessed on 22 May 2020).

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J.-P.; Westman, M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Traumatic stress: A theory based on rapid loss of resources. Anxiety Res. 1991, 4, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Lilly, R.S. Resource conservation as a strategy for community psychology. J. Community Psychol. 1993, 21, 128–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleuren, B.P.; Poesen, L.T.; Gifford, R.E.; Zijlstra, F.R.; Ruwaard, D.; van de Baan, F.C.; Westra, D.D. We’re not gonna fall: Depressive complaints, personal resilience, team social climate, and worries about infections among hospital workers during a pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, S.F.; Wang, M.; Tang, M.; Saeed, A.; Iqbal, J. How toxic workplace environment effects the employee engagement: The mediating role of organizational support and employee wellbeing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; He, J.; Morrison, A.M.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A. Effects of tourism CSR on employee psychological capital in the COVID-19 crisis: From the perspective of conservation of resources theory. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 2716–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, M.; Irshad, M.; Bartels, J. The interactive effect of COVID-19 risk and hospital measures on turnover intentions of healthcare workers: A time-lagged study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Eyoun, K. Do mindfulness and perceived organizational support work? Fear of COVID-19 on restaurant frontline employees’ job insecurity and emotional exhaustion. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, S.; Huang, Y.; Chang, C.H.D. Supporting interdependent telework employees: A moderated-mediation model linking daily COVID-19 task setbacks to next-day work withdrawal. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 1408–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, M.; Irshad, M.; Fatima, T.; Khan, J.; Hassan, M.M. Relationship between problematic social media usage and employee depression: A moderated mediation model of mindfulness and fear of CoViD-19. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S.J.; Huang, C. COVID-19 and health-care worker’s combating approach: An exhausting job demand to satisfy. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2021, 32, 848–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Li, D.; Wang, H.-J. COVID-19-induced layoff, survivors’ COVID-19-related stress and performance in hospitality industry: The moderating role of social support. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, V.; Yadav, J.; Bajpai, L.; Srivastava, S. Perceived stress and psychological well-being of working mothers during COVID-19: A mediated moderated roles of teleworking and resilience. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2021, 43, 1290–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F.; Dik, B.J.; Duffy, R.D. Measuring meaningful work: The Work and Meaning Inventory (WAMI). J. Career Assess. 2012, 20, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Allan, B.A.; Batz-Barbarich, C.; Sterling, H.M.; Tay, L. Outcomes of meaningful work: A meta-analysis. J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 56, 500–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dik, B.J.; Duffy, R.D. Calling and vocation at work: Definitions and prospects for research and practice. Couns. Psychol. 2009, 37, 424–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graeber, D. On the phenomenon of bullshit jobs: A work rant. STRIKE Mag. 2003, 3, 10–11. Available online: https://www.strike.coop/bullshit-jobs (accessed on 31 May 2020).

- Mael, F.; Ashforth, B. Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 1992, 13, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riketta, M. Organizational identification: A meta-analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 2005, 66, 358–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesenfeld, B.M.; Raghuram, S.; Garud, R. Communication patterns as determinants of organizational identification in a virtual organization. Organ. Sci. 1999, 10, 777–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millward, L.J.; Haslam, S.A.; Postmes, T. Putting employees in their place: The impact of hot desking on organizational and team identification. Organ. Sci. 2007, 18, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Witte, H. On the scarring effects of job insecurity (and how they can be explained). Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2016, 42, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rotundo, M.; Sackett, P.R. The relative importance of task, citizenship, and counterproductive performance to global ratings of job performance: A policy-capturing approach. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Viswesvaran, C.; Ones, D.S. Perspectives on models of job performance. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2000, 8, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.A.; Organ, D.; Near, J.P. Organizational citizenship behavior: Its nature and antecedents. J. Appl. Psychol. 1983, 68, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.L.; Bennett, R.J. A typology of deviant workplace behaviors: A multidimensional scaling study. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 555–572. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, V.K.G.; Teo, T.S.H. Mind your E-manners: Impact of cyber incivility on employees’ work attitude and behavior. Inf. Manag. 2009, 46, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Javed, U.; Shoukat, A.; Bashir, N.A. Does meaningful work reduce cyberloafing? Important roles of affective commitment and leader-member exchange. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2019, 40, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoliel, P.; Somech, A. The health and performance effects of participative leadership: Exploring the moderating role of the Big Five personality dimensions. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2014, 23, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouwerkerk, J.W.; Ellemers, N.; De Gilder, D. Group commitment and individual effort in experimental and organizational contexts. In Social Identity: Context, Commitment, Content; Ellemers, N., Spears, R., Doosje, B., Eds.; Oxford: Blackwell, UK, 1999; pp. 184–204. [Google Scholar]

- Ellemers, N.; De Gilder, D.; Haslam, S.A. Motivating individuals and groups at work: A social identity perspective on leadership and group performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2004, 29, 459–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dick, R.; Grojean, M.W.; Christ, O.; Wieseke, J. Identity and the extra mile: Relationships between organizational identification and organizational citizenship behaviour. Br. J. Manag. 2006, 17, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.S.; Park, T.Y.; Koo, B. Identifying organizational identification as a basis for attitudes and behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 1049–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christ, O.; Van Dick, R.; Wagner, U.; Stellmacher, J. When teachers go the extra-mile: Foci of organizational identification as determinants of different forms of organizational citizenship behavior among schoolteachers. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 73, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciampa, V.; Sirowatka, M.; Schuh, S.C.; Fraccaroli, F.; Van Dick, R. Ambivalent identification as a moderator of the link between organizational identification and counterproductive work behaviors. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 169, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Q.; Zhou, J. Corporate hypocrisy and counterproductive work behavior: A moderated mediation model of organizational identification and perceived importance of CSR. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dalal, R.S. A meta-analysis of the relationship between organizational citizenship behavior and counterproductive work behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1241–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.F.; Liang, J.; Ashford, S.; Lee, C. Job insecurity and organizational citizenship behavior: Exploring curvilinear and moderated relationships. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoss, M.K. Job insecurity: An integrative review and agenda for future research. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1911–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisel, W.D.; Probst, T.M.; Chia, S.L.; Maloles, C.M.; König, C.J. The effects of job insecurity on job satisfaction, organizational citizenship behavior, deviant behavior, and negative emotions of employees. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 2010, 40, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feather, N.T.; Rauter, K.A. Organizational citizenship behaviors in relation to job status, job insecurity, organizational commitment and identification, job satisfaction and work values. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2004, 77, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreurs, B.H.J.; van Emmerik, I.H.; Günter, H.; Germeys, F. A weekly diary study on the buffering role of social support in the relationship between job insecurity and employee performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 51, 259–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, T.M.; Stewart, S.M.; Gruys, M.L.; Tierney, B.W. Productivity, counterproductivity and creativity: The ups and downs of job insecurity. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2007, 80, 479–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoss, M.K.; Probst, T.M. Multilevel outcomes of economic stress: An agenda for future research. In Research in Occupational Stress and Well-Being: The Role of Economic Context on Occupational Stress and Well-Being; Perrewe, P.L., Rosen, C.C., Halbesleben, J.R.B., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2012; Volume 10, pp. 43–86. [Google Scholar]

- Leach, C.W.; Van Zomeren, M.; Zebel, S.; Vliek, M.L.W.; Pennekamp, S.F.; Doosje, B.; Ouwerkerk, J.W.; Spears, R. Group-level self-definition and self-investment: A hierarchical (multi-component) model of in-group identification. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 95, 144–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, C.J.; Pontusson, J. Workers, worries and welfare states: Social protection and job insecurity in 15 OECD countries. Eur. J. Political Res. 2007, 46, 211–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauno, S.; Kinnunen, U. Perceived job insecurity among dual-earner couples: Do its antecedents vary according to gender, economic sector and the measure used? J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2002, 75, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keim, A.C.; Landis, R.S.; Pierce, C.A.; Earnest, D.R. Why do employees worry about their jobs? A meta-analytic review of predictors of job insecurity. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2014, 19, 269–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reicher, S.D.; Spears, R.; Postmes, T. A social identity model of deindividuation phenomena. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 6, 161–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adkins, C.L.; Werbel, J.D.; Farh, J.-L. A field study of job insecurity during a financial crisis. Group Organ. Manag. 2001, 26, 463–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E. Do not cross me: Optimizing the use of cross-sectional designs. J. Bus. Psychol. 2019, 34, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milliken, F.J.; Bechky, B.A. Covid-19 and the Abrupt Change in the Nature of Work Lives: Implications for Identification and Communication. NYU STERN. Available online: http://people.stern.nyu.edu/moliva/syllabi/Bechky_Milliken_changing.work.brief.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2020).

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Spector, P.E.; Bauer, J.A.; Fox, S. Measurement artifacts in the assessment of counterproductive work behavior and organizational citizenship behavior: Do we know what we think we know? J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odone, A.; Signorelli, C.; Stuckler, D.; Galea, S.; the University Vita-Salute San Raffaele COVID-19 literature monitoring working group. The first 10,000 COVID-19 papers in perspective: Are we publishing what we should be publishing? Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, 849–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costello, A.B.; Osborne, J.W. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most out of your data. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2005, 10, 7. [Google Scholar]

| Sector: | N | s | Work % Left | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | |||

| Hospitality and Tourism | 35 | 8.6 | 24.54 a | 39.08 |

| Airline Industry | 21 | 5.1 | 26.29 a | 33.60 |

| Transport and Logistics | 11 | 2.7 | 40.36 ab | 38.91 |

| Culture, Sports, and Leisure | 13 | 3.2 | 45.08 ab | 41.02 |

| Commercial Services | 29 | 7.1 | 58.69 bc | 37.21 |

| (Retail) Trade | 46 | 11.3 | 70.15 bcd | 34.84 |

| Government and Public Administration | 33 | 8.1 | 77.1 2cd | 28.76 |

| Education and Science | 29 | 7.1 | 78.62 cd | 27.90 |

| Healthcare and Welfare | 59 | 14.5 | 79.10 cd | 26.14 |

| Media and Communication | 12 | 6.6 | 85.22 cd | 17.18 |

| Justice and Security | 16 | 3.9 | 90.63 d | 15.63 |

| Financial Services | 26 | 6.4 | 90.77 d | 18.72 |

| Information Technology | 13 | 3.2 | 93.00 d | 9.37 |

| Manufacturing, Production, and Construction | 15 | 3.7 | 93.60 d | 11.72 |

| Other | 35 | 8.6 | 66.66 bcd | 36.49 |

| Not Working (n = 51) | Still (Partly) Working (n = 357) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable: | M (SD) | 95% CI | M (SD) | 95% CI | F (1406) | p | ηp2 |

| Positive Meaning | 4.75 (1.48) | [4.33, 5.16] | 5.27 (1.39) | [5.12, 5.41] | 6.22 | 0.013 | .015 |

| Greater-Good Motivations | 4.22 (1.61) | [3.77, 4.67] | 4.96 (1.63) | [4.80, 5.13] | 9.29 | 0.002 | .022 |

| Identification with Organization | 4.93 (1.77) | [4.44, 5.43] | 5.48 (1.52) | [5.32, 5.64] | 5.54 | 0.019 | .013 |

| Identification with Colleagues | 4.81 (1.62) | [4.35, 5.27] | 5.25 (1.41) | [5.10, 5.39] | 4.12 | 0.043 | .010 |

| Job Insecurity | 4.37 (2.00) | [3.81, 4.93] | 2.93 (2.02) | [2.72, 3.14] | 22.79 | 0.000 | .053 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Normal Job Hours | |||||||||||||

| 2. Work % Left | 0.33 *** | -- | |||||||||||

| 3. Normal Telework % | 0.12 * | 0.03 | -- | ||||||||||

| 4. Increase Telework % | 0.14 ** | 0.22 *** | –0.38 *** | -- | |||||||||

| 5. Positive Meaning | 0.22 *** | 0.08 | –0.06 | –0.02 | -- | ||||||||

| 6. Greater-Good Motivations | 0.13 ** | 0.16 ** | –0.10 | 0.02 | 0.51 *** | -- | |||||||

| 7. Identification with Organization | 0.16 ** | 0.17 ** | –0.09 | 0.07 | 0.57 *** | 0.33 *** | -- | ||||||

| 8. Identification with Colleagues | 0.19 *** | 0.14 ** | –0.04 | -0.00 | 0.51 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.76 *** | -- | |||||

| 9. Job Insecurity | –0.04 | –0.30 *** | –0.05 | 0.03 | 0.05 | –0.09 | –0.04 | .01 | -- | ||||

| 10. Online OCB-I | 0.23 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.10 | 0.20 ** | 0.24 *** | 0.06 | 0.25 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.08 | -- | |||

| 11. Online OCB-O | 0.09 | –0.02 | –0.01 | –0.00 | 0.29 *** | 0.13 * | 0.29 *** | 0.2 6 *** | 0.18 ** | 0.40 *** | -- | ||

| 12. Cyberostracism | 0.07 | –0.01 | 0.14 ** | –0.04 | –0.10 | –0.09 | –0.18 *** | –0.14 * | 0.12 * | 0.09 | 0.22 *** | -- | |

| 13. Cyberincivility | 0.11 * | –0.07 | 0.10 | –0.08 | –0.09 | –0.05 | –0.15 ** | –0.09 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.14 * | 0.43 *** | -- |

| Positive Meaning | Greater-Good Motivations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE B) | 95% CI | p | B (SE B) | 95% CI | p | |

| Age | 0.01 (0.01) | [–0.00, 0.02] | 0.117 | 0.00 (0.01) | [–0.01, 0.02] | 0.545 |

| Gender | 0.26 (0.15) | [–0.03, 0.55] | 0.080 | 0.10 (0.18) | [–0.24, 0.45] | 0.559 |

| Living Situation | 0.18 (0.18) | [–0.18, 0.53] | 0.326 | 0.47 (0.21) | [0.06, 0.89] | 0.026 |

| Increased Care | –0.22 (0.25) | [–0.70, 0.26] | 0.371 | 0.21 (0.25) | [–0.35, 0.78] | 0.459 |

| Supervisory Function | –0.45 (0.17) | [–0.78, –0.13] | 0.006 | –0.35 (0.29) | [–0.73, 0.03] | 0.073 |

| Days in Lockdown | –0.01 (0.01) | [–0.03, 0.02] | 0.699 | –0.04 (0.19) | [–0.07, –0.00] | 0.032 |

| Normal Job Hours | 0.02 (0.01) | [0.01, 0.03] | 0.001 | 0.01 (0.01) | [–0.00, 0.03] | 0.130 |

| Work % Left | 0.00 (0.00) | [–0.00, 0.00] | 0.899 | 0.01 (0.00) | [0.00, 0.01] | 0.014 |

| Model | N = 408; R2 = 0.08, F (8, 399) = 4.38, p < 0.001 | N = 408; R2 = 0.06, F (8, 399) = 3.35, p < 0.001 | ||||

| Identification with Organization | Identification with Colleagues | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE B) | 95% CI | p | B (SE B) | 95% CI | p | |

| Age | 0.02 (0.01) | [0.01, 0.03] | 0.002 | 0.02 (0.01) | [0.01, 0.03] | 0.000 |

| Gender | 0.22 (0.17) | [–0.10, 0.55] | 0.178 | 0.32 (0.15) | [0.02, 0.61] | 0.037 |

| Living Situation | 0.19 (0.07) | [–0.21, 0.58] | 0.354 | 0.20 (0.18) | [–0.16, 0.56] | 0.269 |

| Increased Care | –0.17 (0.20) | [–0.70, 0.37] | 0.537 | –0.10 (0.25) | [–0.58, 0.39] | 0.703 |

| Supervisory Function | –0.37 (0.27) | [–0.73, –0.01] | 0.043 | –0.47 (0.17) | [–0.80, –0.14] | 0.005 |

| Days in Lockdown | –0.02 (0.18) | [–0.05, 0.01] | 0.151 | –0.01 (0.02) | [–0.04, 0.02] | 0.491 |

| Normal Job Hours | 0.01 (0.01) | [–0.01, 0.02] | 0.197 | 0.01 (0.01) | [0.00, 0.02] | 0.055 |

| Work % Left | 0.01 (0.00) | [0.00, 0.01] | 0.015 | 0.00 (0.00 | [–0.00, 0.01] | 0.128 |

| Model | N = 408; R2 = 0.08, F (8, 399) = 4.44, p < 0.001 | N = 408; R2 = 0.10, F (8, 399) = 5.58, p < 0.001 | ||||

| Job Insecurity | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE B) | 95% CI | p | |

| Age | –0.00 (0.00) | [–0.02, 0.01] | 0.558 |

| Gender | 0.25 (0.21) | [–0.17, 0.67] | 0.249 |

| Living Situation | –0.36 (0.26) | [–0.87, 0.15] | 0.166 |

| Increased Care | –0.11 (0.35) | [–0.80, 0.58] | 0.757 |

| Supervisory Function | 0.19 (0.24) | [–0.28, 0.65] | 0.425 |

| Days in Lockdown | 0.07 (0.02) | [0.03, 0.11] | 0.001 |

| Normal Job Hours | 0.01 (0.01) | [–0.01, 0.03] | 0.199 |

| Work % Left | –0.02 (0.00) | [–0.02, –0.01] | 0.000 |

| Model | N = 408; R2 = 0.13, F (8, 399) = 7.20, p < 0.001 | ||

| Online OCB-I | Online OCB-O | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE B) | 95% CI | p | B (SE B) | 95% CI | p | |

| Age | –0.00 (0.01) | [–0.01, 0.01] | 0.433 | –0.02 (0.01) | [–0.03, –0.01] | 0.002 |

| Gender | 0.03 (0.16) | [–0.28, 0.34] | 0.849 | 0.28 (0.18) | [–0.07, 0.63] | 0.114 |

| Living Situation | –0.15 (0.19) | [–0.51, 0.22] | 0.426 | 0.03 (0.21) | [–0.38, 0.45] | 0.879 |

| Increased Care | –0.28 (0.24) | [–0.76, 0.20] | 0.257 | 0.20 (0.28) | [–0.34, 0.74] | 0.458 |

| Supervisory Function | –0.55 (0.17) | [–0.88, –0.21] | 0.001 | –0.23 (0.19) | [–0.61, 0.15] | 0.234 |

| Days in Lockdown | –0.02 (0.02) | [–0.05, 0.01] | 0.235 | 0.03 (0.02) | [–0.01, 0.06] | 0.127 |

| Normal Job Hours | 0.01 (0.01) | [–0.00, 0.03] | 0.069 | 0.01 (0.01) | [–0.00, 0.03] | 0.195 |

| Work % Left | 0.00 (0.00) | [–0.00, 0.01] | 0.107 | –0.00 (0.00) | [–0.01, 0.00] | 0.546 |

| Normal Telework % | 0.01 (0.00) | [0.01, 0.02] | 0.000 | 0.00 (0.00) | [–0.00, 0.01] | 0.426 |

| Increase Telework % | 0.01 (0.00) | [0.01, 0.02] | 0.000 | 0.00 (0.00) | [–0.01, 0.00] | 0.838 |

| Positive Meaning | 0.15 (0.07) | [0.01, 0.29] | 0.033 | 0.12 (0.08) | [–0.04, 0.28] | 0.139 |

| Greater-Good | –0.06 (0.05) | [–0.16, 0.04] | 0.221 | 0.01 (0.06) | [–0.11, 0.12] | 0.914 |

| Identification (O) | –0.05 (0.08) | [–0.21, 0.11] | 0.517 | 0.18 (0.09) | [0.00, 0.36] | 0.048 |

| Identification (C) | 0.28 (0.08) | [0.13, 0.43] | 0.000 | 0.11 (0.09) | [–0.07, 0.28] | 0.223 |

| Job Insecurity | 0.07 (0.04) | [–0.00, 0.14] | 0.054 | 0.12 (0.04) | [0.04, 0.20] | 0.004 |

| Model | N = 318; R2 = 0.27, F (15, 302) = 7.48, p < 0.001 | N = 318; R2 = 0.18, F (15, 302) = 4.37, p < 0.001 | ||||

| Cyberostracism | Cyberincivility | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE B) | 95% CI | p | B (SE B) | 95% CI | p | |

| Age | –0.01 (0.00) | [–0.02, –0.01] | 0.000 | –0.00 (0.00) | [–0.01, 0.00] | 0.546 |

| Gender | –0.07 (0.09) | [–0.25, 0.12] | 0.483 | –0.11 (0.06) | [–0.23, 0.02] | 0.094 |

| Living Situation | 0.25 (0.11) | [0.03, 0.46] | 0.027 | 0.04 (0.07) | [–0.10, 0.19] | 0.571 |

| Increased Care | 0.02 (0.14) | [–0.27, 0.30] | 0.918 | 0.10 (0.10) | [–0.09, 0.29] | 0.288 |

| Supervisory Function | –0.09 (0.10) | [–0.29, 0.11] | 0.381 | –0.20 (0.07) | [–0.33, 0.07] | 0.003 |

| Days in Lockdown | –0.00 (0.01) | [–0.02, 0.01] | 0.656 | –0.01 (0.01) | [–0.02, 0.01] | 0.273 |

| Normal Job Hours | 0.01 (0.00) | [–0.00, 0.02] | 0.072 | 0.00 (0.00) | [–0.00, 0.01] | 0.131 |

| Work % Left | 0.00 (0.00) | [–0.00, 0.00] | 0.857 | –0.00 (0.00) | [–0.00, 0.00] | 0.439 |

| Normal Telework % | 0.00 (0.00) | [0.00, 0.01] | 0.026 | 0.00 (0.00) | [–0.00, 0.00] | 0.296 |

| Increase Telework % | 0.00 (0.00) | [–0.00, 0.00] | 0.997 | 0.00 (0.00) | [–0.00, 0.00] | 0.724 |

| Positive Meaning | –0.01 (0.04) | [–0.10, 0.07] | 0.756 | –0.02 (0.03) | [–0.08, 0.03] | 0.413 |

| Greater-Good | –0.02 (0.03) | [–0.08, 0.04] | 0.602 | 0.00 (0.02) | [–0.04, 0.04] | 0.852 |

| Identification (O) | –0.07 (0.05) | [–0.16, 0.02] | 0.142 | –0.06 (0.03) | [–0.12, 0.01] | 0.070 |

| Identification (C) | 0.01 (0.05) | [–0.09, 0.10] | 0.914 | 0.01 (0.03) | [–0.05, 0.08] | 0.664 |

| Job Insecurity | 0.05 (0.02) | [0.01, 0.10] | 0.012 | 0.03 (0.01) | [0.00, 0.06] | 0.027 |

| N = 318; R2 = 0.13, F (15, 302) = 3.01, p < 0.001 | N = 318; R2 = 0.11, F (15, 302) = 2.60, p = 0.001 | |||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ouwerkerk, J.W.; Bartels, J. Is Anyone Else Feeling Completely Nonessential? Meaningful Work, Identification, Job Insecurity, and Online Organizational Behavior during a Lockdown in The Netherlands. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1514. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031514

Ouwerkerk JW, Bartels J. Is Anyone Else Feeling Completely Nonessential? Meaningful Work, Identification, Job Insecurity, and Online Organizational Behavior during a Lockdown in The Netherlands. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(3):1514. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031514

Chicago/Turabian StyleOuwerkerk, Jaap W., and Jos Bartels. 2022. "Is Anyone Else Feeling Completely Nonessential? Meaningful Work, Identification, Job Insecurity, and Online Organizational Behavior during a Lockdown in The Netherlands" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 3: 1514. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031514

APA StyleOuwerkerk, J. W., & Bartels, J. (2022). Is Anyone Else Feeling Completely Nonessential? Meaningful Work, Identification, Job Insecurity, and Online Organizational Behavior during a Lockdown in The Netherlands. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1514. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031514